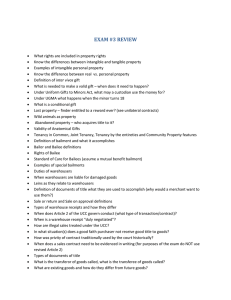

UCC Breach of Warranty and Contract Claims

advertisement