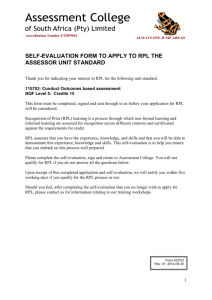

Recognition of Prior Learning in the context of the South African NQF

advertisement