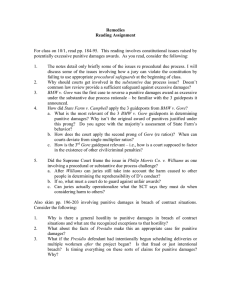

Procedural Due Process and Predictable Punitive Damage Awards

advertisement