Application of the Floating Wye Connection

advertisement

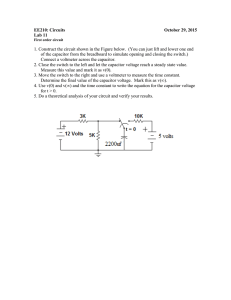

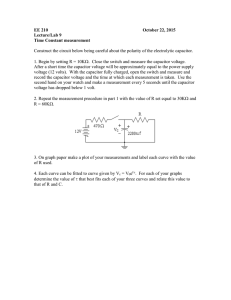

Application of the Floating Wye Connection By Neal S. Ciurro Floating Wye Capacitor Much has been said and written regarding the benefits and advantages of connecting banks in a wye configuration with the neutral point grounded (grounded wye) or ungrounded (floating wye). High Fault Current One of the concerns with a capacitor bank is when the available fault current is of high magnitude. When one capacitor unit fails and just before its fuse clears, all of the available fault current will "dump" into this faulted unit. This could result in a violent rupture of the faulted unit, possible damage of other equipment, and costly outages. One possible solution is to use current limiting fuses which have interrupting ratings as high as 50kA. However, normally capacitor substation blocks (outdoor, open structures) are of larger (kVAR) size and this could be expensive. Another more effective method is to float the neutral (ungrounded wye) in a floating wye capacitor configuration. The fault current is held to three-times the line current [refer to Appendix 1] eliminating the concern of high fault current damaging other good capacitors and possibly rupturing the faulted capacitor. Floating Neutral A little mathematical analysis can show why this is so. Figure 1 shows a balanced floating capacitor bank. Let 1 PU (per unit) equal VaN, VbN, and VcN. Figure 1 Figure 2 Assume a capacitor is failing in Leg (a). Just before the fuse attached to the capacitor clears, the neutral (N) shifts to Va. (See Figure 2). There is an increase in voltage across the capacitors in lines VcN' and VbN'. This increase is intuitively 1.73 x VN or 1.73 x (1 PU). However, in pure mathematics, we cannot accept intuitive logic. This will need to be proven. There are a few methods of proving this. One is mathematical and the other is analytical. The mathematical solution uses the Law of Cosines. Mathematical Solution When the neutral shifts from N to N' (again see Figure 2), N' is at the same potential as Va. This happens as a capacitor in this leg starts to fail and prior to the fuse of the failing capacitor clearing. The Law of Cosines is (b')2 = a2 + b2 + 2abCosØ. Using Figure 2, we have: (b')2 a2 b2 CosØ = = = = (VbN')2 (N'N)2 or (1 PU)2 (VbN)2 or (1 PU)2 (-0.5), Ø = 120° Then (VbN')2 = (1)2 +(1)2 + 2(-0.5) (VbN') =2+1=3 b' = 1.73 (VbN') = 1.73 (1 PU) Analytical Solution If an analytical approach is preferred, we can solve the voltage problem this way, which allows us to use the same assumptions we used for the mathematical solution and let the same capacitor fail, we can develop Figure 3. The triangles N', N, Vb: N', N, Vc are equal. Also, the center angles are all equal (120°). Therefore, triangle N', Vb, Vc is an equilateral triangle. Figure 3 Figure 4 A perpendicular line is drawn from N to E. Based on the fact that the triangle is equilateral, this line not only bisects the angle(Vb, N, Va), it segments the line b' into two equal parts (VbE and N'E). Isolating triangle E, Vb, N, we have the following (see Figure 4). Then (EN) = sin 30°. Therefore, EN = 0.5 And VbE - cos 30°.Therefore, VbE= 0.866 Proving Line VbE is 0.866, then Line EN' = 0.866 + 0.866 = 1.73 and voltage across leg VbN' is 1.73 x 1PU. The shift in the capacitor current has the same effect as the voltage shift. Of course, the current is leading the voltage by 90°. The Phasor Diagram for the current in this condition is shown in Figure 5. (Capacitors are shown for reference only). Figure 5 Figure 6 Using Kirchoff's Law, we have: In = IØa + IØb + IØc = 0 Again, if a unit fails and before the fuse clears, we have a neutral shift in current. When this occurs, we then have the condition shown in Figure 6. In Figure 5, In = 0. However, in Figure 6, IØa is now considered In'; and because of Kirchoff's Law, we have IN = IØb + IØc. Under normal conditions, IØa = IØb = IØc, but as shown in the voltage calculation when the unit in leg (a) begins to fail, Vb = Vc = (1.73 x 1 PU). The same calculations apply in the current calculations. Therefore, IØb = IØc = (1.73 x normal line current). Using Polar and Complex calculations (see Figure 6), we have the following: Therefore, IN' = 3 times normal line current. A more graphic approach would be by using vectors (see Figure 7). Figure 7 A = B = 1.73. Therefore, Figure 7 is a rhombus. The diagonals of a rhombus intersect at right angles. Also, the diagonals divide the rhombus into four equal and congruent triangles. Then Vectoriallly: A + B=2C C=(cos 30°)(1.73) C=(0.866)(1.73) C=1.5 Therefore 2C=3 Summary There are advantages in both grounded and floating wye banks. However, floating wye banks can be used on both 3 phase, 3 wire and 3 phase, 4 wire systems. As shown in the analogy, a major advantage in using a floating wye bank is when the fault current is of a high magnitude. The floating wye bank will limit the fault current to three times the line current. APPENDIX (1) Proof that the fault current in a capacitor is limited to three times the line current for an ungrounded wye capacitor bank. First we will look at what happens to the voltage when a capacitor fails in one phase just before the fuse clears the faulted capacitor. Figure 1 shows a balanced floating wye capacitor connection. Let 1 PU (per unit) equal VaN, VbN and VcN. Assume a capacitor is failing in leg (a). Just before the fuse attached to this capacitor clears, the neutral (N) shifts to Va or, N’. See figure 2. There is an increase in voltage across the capacitors in lines VbN’ and VcN’. As the capacitor fails and prior to the capacitor fuse clearing the neutral will shift from N to N’. Calculating the legs of the triangle created by sides b =(VbN), a=(VaN) and b’= (VbN’) we can use the law of Cosines: (b’)2 = a2 + b2 –2ab(CosN ) (b’)2 = (VbN’) But a=VaN =b=VbN=NN’=1PU, then a2 = b2 = 1 N = 1200 CosN = (-0.5) Then (VbN’)2 = 12 + 12 – 2(1)(1)(-0.5) = 3 (VbN’) = sqrt(3) or, approximately 1.73205 Using this knowledge for our vector analysis we will let Side a = Side b = sqrt(3). Therefore, the voltage on these legs will be at line-to-line potential. The shift in the capacitor current will have the same effect as the voltage shift. Under normal conditions the current leads the voltage by 90o . See figure 3. Using Kirchhoff’s law, under balance conditions, we have: IN = IØa + IØb + IØc = 0 When the failure in leg (a) occurs as described above, the current will change accordingly. See figure 4. In figure 3, IN = 0. However, IN shifts to IØa position and is now considered IN’. Again using Kirchhoff’s law we have the following: IN’ = IØb + IØc Under normal conditions IØa = IØb = IØc, but as shown in the voltage calculation when unit in leg (a) begins to fail, Vb = Vc = (sqrt(3) * 1pu.) The same calculations will apply in the current calculations and IØb = IØc, = (sqrt(3) * normal line current.) Using Polar and Complex number calculations from figure 4, we have the following: IN’ = (sqrt(3) * ∠330O) + (sqrt(3) * ∠30O) = (1.5 - j0.866) + (1.5 + j0.866) = (3 ± j0) Therefore, IN’ = 3 times normal line current. See figure 5 for a vectorial solution. You will note that the figure is a Rhombus. The diagonals of a Rhombus intersect at right angles. Also, the diagonals divide the Rhombus into four equal and congruent triangles. Then A = B, let A and B equal (sqrt(3)). Then we have the following: Vector A + Vector B = 2C (Resultant) C = (Cos300)(sqrt(3)) C = (0.866)(sqrt(3)) C = 1.5 ∴ 2C=3