Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the

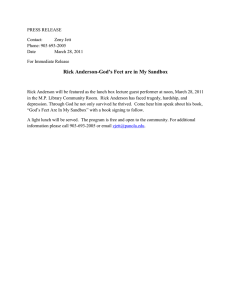

advertisement