Law for Life Legal Capability for Everyday Life Evaluation report

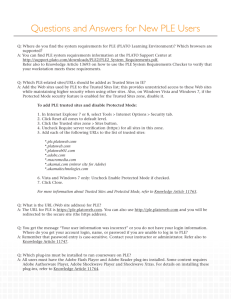

advertisement