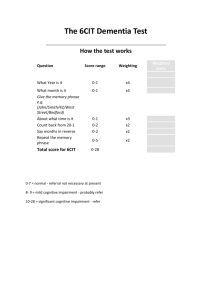

Cognitive impairment and its consequences in everyday life

advertisement