Applied Strength of Materials for Engineering Technology

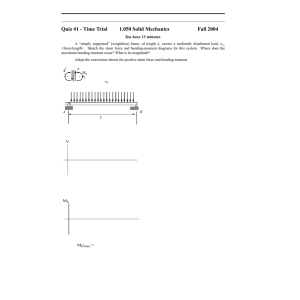

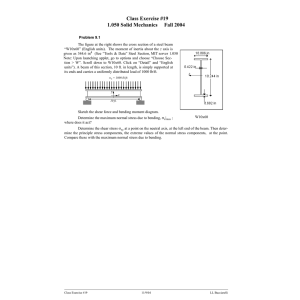

advertisement