IEEE Guide for the Application of Faulted Circuit Indicators

advertisement

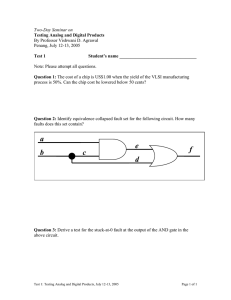

IEEE Guide for the Application of Faulted Circuit Indicators Discussion Group - B17D March 2012 Seattle Fran Angerer, Chair Brieana Reed-Harmel, Vice-Chair Frank DiGuglielmo John Hans Fred Koch John Banting Gene Weaver Tim Robeson Mark Boettcher Brieana Reed Harmel Farris Jibril Agenda March 26, 2012 Introductions Call for essential patents Approval of Minutes Review modified Draft of P1610 Discuss Additional Changes for Application Guide Actions and next meeting Adjournment Call for Essential Patents IEEE-SA Standards Board Bylaws on Patents in Standards 6. Patents IEEE standards may include the known use of essential patents and patent applications provided the IEEE receives assurance from the patent holder or applicant with respect to patents whose infringement is, or in the case of patent applications, potential future infringement the applicant asserts will be, unavoidable in a compliant implementation of either mandatory or optional portions of the standard [essential patents]. This assurance shall be provided without coercion and prior to approval of the standard (or reaffirmation when a patent or patent application becomes known after initial approval of the standard). This assurance shall be a letter that is in the form of either: a) A general disclaimer to the effect that the patentee will not enforce any of its present or future patent(s) whose use would be required to implement either mandatory or optional portions of the proposed IEEE standard against any person or entity complying with the standard; or b) A statement that a license for such implementation will be made available without compensation or under reasonable rates, with reasonable terms and conditions that are demonstrably free of any unfair discrimination. This assurance shall apply, at a minimum, from the date of the standard's approval to the date of the standard's withdrawal and is irrevocable during that period. Inappropriate Topics for IEEE WG Meetings Don’t discuss the validity/essentiality of patents/patent claims Don’t discuss the cost of specific patent use Don’t discuss licensing terms or conditions Don’t discuss product pricing, territorial restrictions, or market share Don’t discuss ongoing litigation or threatened litigation Don’t be silent if inappropriate topics are discussed… do formally object. If you have questions, contact the IEEE-SA Standards Board Patent Committee Administrator at patcom@ieee.org or visit http://standards.ieee.org/board/pat/index.html This slide set is available at http://standards.ieee.org/board/pat/pat-slideset.ppt B17D – GUIDE FOR APPLICATION OF UNDERGROUD FAULT CURRENT INDICATORS Fran Angerer, Chair – Jerry Harness, Vice-Chair Location: Denver, CO Date: October 24, 2011 Meeting was brought to order by Chairman Fran Angerer at 10:35 AM. Approximately 12 in attendance Introductions Review of Agenda Call for Patents The DG Chair provided an opportunity for participants to identify patent claims, patent application claims, or patent application claims of which the participant is personally aware and that may be essential for the use of this standard. No patent claims, patent application claims, or holders of patent claims or patent application claims have been identified at this time. Approved Minutes from the Spring 2011 Meeting, May 2011 at St. Pete Beach, FL Announced need for new group vice chair – Volunteer: Brieana Reed-Harmel Application for PAR was dismissed due to IEEE 1216 was under the authority of T&D Committee. John Banting requested the authority to be changed to ICC so that B17D could re-apply for PAR. Current Volunteers for Working Group Fred Koch John Hans Eugene Weaver Tim Robeson Fran Angerer Brieana Reed-Harmel Mark Boettcher Farris Jibril Ken Lee Discussed Additional Topics for Application Guide Lightening Strokes Multiple OH faults & Sequential Faults Momentary Fault Display vs. Permanent Fault Display Add Pictorials Section on new application of FCI’s (Network Indicators, Data Collectors, Smart Sensors) Discussed Section 5 of proposed draft guide document Future Work (Action Items): Group will apply for a PAR for the Application Guide to replace 1216 and 1610. Next meeting group will review IEEE 495 to decide if it needs revision. Next Meeting at Seattle, WA, March 25-28, 2012. Meeting adjourned. 12:18 PM Possible Additional Subject Topics for New Application Guide FCI response to Sequential multiple faults on OH lines? Lightning Strokes and FCIs. FC I response on Phase to Phase faults. (Other Suggestions?) 4. Application of FCIs Underground and Overhead FCIs are applied to monitor conductors at switchgear, transformers, junctions, and at cable dips, risers, etc. FCIs are attached to conductors, terminations or test points to sense for abnormally high currents typically associated with faults. FCIs trip with a visual, audible, radio or remote indication when they have sensed conditions that are determined to indicate an overcurrent has passed its location. FCIs located along the fault current path will trip to indicate a “FAULT” while those that do not determine a fault current has passed its location will remain “NORMAL”. Operating personnel locate the faulted section between the last FCI displaying “FAULT” and the first FCI displaying “NORMAL”. Three-phase, residential distribution circuits can be radial or looped. Looped circuits typically have an open point. When choosing the placement of FCIs, consideration between cost and customer reliability should be made. FCIs could be placed on both the incoming and outgoing cables of each transformer. This would provide the most knowledge on where the fault is located since information would be available to differentiate between cable faults and faults on the high voltage bus in the transformer. Evidence has shown that primary cable faults are much more prevalent than high voltage bus faults in the transformer. To address the problem of cable faults, FCIs need only be placed on the outgoing cables of each transformer. Further reduction in the number of FCIs installed could be realized by locating them at every other transformer or less. However, for each reduction in the number of FCIs, the time to locate and isolate the faulted cable will increase. The customer outage time will also increase. Faulted circuit indicators are affected by many items including cold load pickup, inrush, switching surges and power follow currents. Proper application is essential to proper operation. FCI’s should avoid tripping on inrush, cold load pickup and switching surges and operate before protective devices. 4.0 Types of FCIs 4.1 Manual Reset Manual reset FCIs require an operator to check and reset each indicator after each fault event. The large variety of system conditions that occur on a distribution system makes it very difficult to create generalized application rules. Failure to reset the indicator can cause confusion for subsequent faults. Mechanical FCIs do not employ inrush restraint 4.2 Automatic Reset FCIs are available with a variety of resetting means that return a tripped unit to its normal state. Automatic reset types include reset by voltage, current, time or combinations of each. 4.2.1 Current reset Current reset FCIs will reset their indication when load current is sensed. Contact manufacturer for load sensitivity. 4.2.2 Voltage Reset Voltage resetting fault indicators are not affected by load current. Voltage resetting FCIs can be used on overhead or underground systems. There are several types of voltage resetting devices. The high (primary) voltage resetting devices depend on the electrostatic field surrounding a high voltage cable or a separable connector’s capacitive test point for operating power. The electrostatic reset type requires that the cable be unshielded and a test point reset type requires the use of a test point type separable connector. The low (secondary) voltage resetting devices can only be applied wherever a secondary voltage is available and do not require a “test point type separable connector”. 4.2.3 Time Reset Time reset FCIs will reset after a period of time. When choosing the length of time before reset, the time chosen should be long enough to allow operating personnel time to locate and isolate the fault. If some or all of the units reset before this is accomplished, confusing information as to the location of the fault exists. In contrast, choosing an excessively long time can also cause problems if there is a subsequent fault before the units have had a chance to reset. 4.3 FCI Display The basic function of an FCI is to detect fault currents and provide evidence that fault current was detected. There are a variety of FCI display options available. The first decision is the type of display. The display can be a mechanical flag, audible alarm, light, or counter. When choosing an FCI display, the second consideration is whether the display is to be remote or non-remote. The non-remote display can be located on the primary cable immediately below the termination or on an elbow test point.. This arrangement has the disadvantage of having to open the enclosure or substructure to observe the display. The remote display can be mounted so that it is visible without opening the enclosure. This design requires a sensor on the cable termination or elbow test point that can be connected to the remote display via cables, optics, or other means. 4.4 Self adjusting FCIs Adaptive trip FCIs automatically adjust the trip point depending on sensed load. These devices are “one size fits all” and can eliminate the need to have many different fixed trip levels. 5. Three-phase Distribution Circuit Considerations 5.1 Introduction An example of a distribution system, with various components and line segments is illustrated in Figure 1. The figure shows a 600A underground three-phase circuit getaway from a distribution substation, and includes a combination of 3∅ overhead and underground portions, and 1∅ overhead and underground looped laterals. A looped circuit is a common distribution system feeder design and can be fully or partially fed by closing an open tie, should normal service be disrupted. Distribution line voltages generally range from 5 kV to 46 kV and feeder circuit ratings are generally in the 600-amp range. Available short circuit current at the feeder breaker depends upon the size of the substation transformer, circuit impedance and system voltage, but generally range from 2,000 to 12,000 amps but may in some cases exceed these values. Figure 1 – Example distribution circuit 5.2 Fault types A fault is an abnormal condition where there is an electrical short circuit between an energized phase conductor and ground or two or more dissimilar phase conductors. Faults can occur from a variety of sources. Several examples are listed below: • cable insulation, joint or termination failures • digging into underground cables • dielectric failures of electrical equipment • tree limbs that fall onto overhead phase wires • overhead wires contacting each other during high winds • vehicle accidents with overhead poles or pad mounted distribution equipment • wildlife contacting energized conductors • contaminated insulators that flash-over In order to properly apply Faulted Circuit Indicators (FCIs) and understand potential causes of operational issues, one must consider the different types of faults, which can occur on an underground distribution system. These faults are generally limited to two types: low impedance and high impedance. FCIs are designed to detect low impedance faults and cannot respond reliably to high impedance faults. FCIs are designed to detect high magnitude fault current that is typically sufficient to initiate breaker or recloser tripping or fuse operation. •The trip response should coordinate with all protective devices to ensure that the FCI will trip under most low impedance fault conditions. The user should consider coordination with current-limiting fuses due to their fast sub-cycle clearing time. Current Limiting Fuse protection may require FCIs to respond as fast as ¼ cycle. 5.2.1 Low impedance faults Low impedance faults, or bolted faults can be either very high in current magnitude (10,000 amperes or above) or fairly low, e.g. 300 amperes at the end of a long feeder. Faults able to be detected by high energy protective devices for solidly grounded systems are all considered low impedance faults. The fault impedance of most detectable faults is close to 0 ohms. This implies that the phase conductor either contacts the neutral wire or that the arc to the neutral conductor has a very low impedance. The maximum fault impedance of a detectable fault is approximately 2 ohms or less. As indicated in figure 2, 2 ohms of fault impedance decreases the level of fault current for close-in faults, but has little effect for faults some distance away. If values of 2 ohms or less are used in calculations considering low impedance detectable faults, the result of those calculations will be very close to the actual fault levels present in the distribution system. [B3] 5.2.2 High impedance faults High impedance faults are not detectable by normal protection means. This implies that high impedance faults do not contact the neutral, do not arc to the neutral, or there is not enough voltage to establish a low impedance earth return path. As a result, these types of faults are not detectable by conventional protection devices. Fault indicators sense over-current conditions and as such, cannot be used to reliably detect high impedance faults. 5.2.1 Low impedance faults Low impedance faults, or bolted faults can be either very high in current magnitude (10,000 amperes or above) or fairly low, e.g. 50 amperes at the end of a long feeder. Faults able to be detected by high energy protective devices for solidly grounded systems are all considered low impedance faults. The fault impedance of most detectable faults is close to zero ohms. This implies that the phase conductor either contacts the neutral wire or that the arc to the neutral conductor has a very low impedance. The maximum fault impedance of a detectable fault is approximately two ohms or less. As indicated in Figure 2, two ohms of fault impedance decreases the level of fault current for close-in faults, but has little effect for faults some distance away. If values of two ohms or less are used in calculations considering low impedance detectable faults, the result of those calculations will be very close to the actual fault levels present in the distribution system. [B3] 5.3 Reclosing, re-fusing and inrush For protected circuits, re-fusing or reclosing may result in inrush currents when the equipment beyond the load is re-energized. The magnitude of this inrush current is affected by the type of equipment, system impedance, load characteristic, and pointon-wave when the circuit is energized. See Figure 2. For a common protective reclosing sequence, the inrush current on the reclose cycle may exceed the trip level of the FCI on the un-faulted phases. The end user must be aware of the possibility of high inrush currents resulting in the FCI tripping. Inrush could be a problem on distribution circuits. If inrush is a concern (usually because fault levels are very low, requiring FCIs with low trip), then precautions must be taken to prevent operation of FCIs. A variety of inrush restraints are available from manufacturers. Some use time/current response curves, while others use inrush restraint logic. Considering that the time/current characteristics of a fuse curve and an inrush curve are similarly shaped with the inrush curve lying to the left of the fuse curve, as shown in Figure 3. An FCI trip response must lie between the inrush curve and the protection curve to assure coordination. If it is coordinated, the FCI will not trip on inrush, but will trip before the protection clears. 25 0 P.U. of Connected Load 5 10 15 20 Transformers Laterals Feeders Figure 2 – Typical magnitudes of inrush current FCI Response should be between these curves Protection curve Inrush curve Figure 3 - FCI Trip Response 5.3.1 Cold load pickup Cold load pickup results from the re-energization of a circuit following a long outage. It is often the cause of some protective device mis-operations, since there is no actual fault in the circuit. Figure 4 illustrates several cold load pickup curves developed by various sources. These curves are normally considered to be comprised of the following three components: Inrush – lasting a few cycles Motor starting – lasting a few seconds Loss of diversity – lasting many minutes When a fuse operates as a result of cold load pickup, it is most likely due to a loss of diversity. Since fuses are often sized for coordination, not load, this condition is rare on most laterals. Relay operation during cold load pickup is generally the result of a trip on the instantaneous unit and probably results from high inrush. Likewise, an FCI operation would not appear to be the result of loss of diversity but rather the high inrush currents. Loss of Diversity Figure 4 – Cold load inrush current characteristics for distribution circuits 5.4 Interference Energy 5.4.1 Backfeed Energy Backfeed is caused by the release of energy stored in various components of the distribution system, or the loads attached to it. If a fault occurs on the system, the impedance of the circuit can fall to very low levels. In this case, the energy stored in the capacitance or inductance of the circuit can result in relatively large current flowing through the cable and into the fault. The backfeed energy flows in a direction opposite of normal flow and can influence FCIs downstream from the fault. Sources of backfeed energy include: Capacitor banks, Cable discharge. Rotating Machinery Proximity Energy Single-phase protection on three-phase loads Distributed Generation 5.4 Interference Energy 5.4.1 Backfeed Energy Backfeed is caused by the release of energy stored in various components of the distribution system, or the loads attached to it. If a fault occurs on the system, the impedance of the circuit can fall to very low levels. In this case, the voltage stored in the capacitance or inductance of the circuit can result in relatively large current flowing through the cable and into the fault. The backfeed energy flows in a direction opposite of normal flow and can influence FCIs downstream from the fault. Sources of backfeed energy include: Capacitor banks, Cable discharge. Motors, Proximity Energy Single-phase protection on three-phase loads 5.4.1.1 Capacitor banks A situation where backfeed energy could cause a false trip is on a single-phase fault in three-phase circuits with three-phase capacitor banks and single-phase tripping feature. When a single-phase fault occurs and opens the single-phase protection, the two unfaulted phases will remain energized. The capacitors connected to the faulted phase will discharge into the fault. If the circuit impedance is low enough and if the capacitors were nearly charged to peak voltage at the time of the fault, the FCI installed between the capacitors and the fault could be tripped. The duration of this discharge is brief, but can be a concern as a cause for an FCI to trip. Capacitor Discharge to Fault FCI FCI Figure 5 5.4.1.1 Capacitor banks A situation where backfeed current could cause a false trip is on a single-phase fault in three-phase circuits with three-phase capacitor banks and single-phase tripping feature. When a single-phase fault occurs and opens the single-phase protection, the two unfaulted phases will remain energized. The capacitors connected to the faulted phase will discharge into the fault. If the circuit impedance is low enough and if the capacitors were nearly charged to peak voltage at the time of the fault, the FCI installed between the capacitors and the fault could be tripped. The duration of this discharge is brief, but can be a concern as a cause for an FCI to trip. 5.4.1.2 Cable discharge A similar discharge can result from cable discharge due to the capacitance of the underground cable. The cable downstream from a fault will discharge back to the fault, which could cause an FCI to false trip. The length of the cable changes the frequency and duration of the discharge, whereas the voltage and cable type will control the peak discharge current. Need permission from Cooper and reference. Figure 6 Figure 6 shows a simplified 25 kV distribution cable system with a fault having a variable amount of cable behind it. Assuming that the copper 1/0 cable has an L = 196.3 uH per foot and C = 59 nF per foot, the discharge frequency can be calculated: f = 1/(2π√LC) If there is 1000’ of cable behind the fault then f = 46.77 kHz 5.4.1.3 Rotating machinery (motors) Rotating machinery after a fault can produce backfeed current that flows to the fault from downstream sources that can trip or reset FCIs. The magnitude and duration are typically very low, however, they can result in energy levels sufficient to trip or reset FCIs, depending on the system impedance. 5.4.1.4 Proximity Energy The influence of current or voltage from adjacent conductors or circuits on the operation of a FCI is known as Proximity Effect. The effect can occur in a number of different ways. Multi-phase circuit conductors could be very close together. The close proximity of the conductors can make it difficult for FCIs to properly distinguish between the various magnetic or voltage fields generated during a fault, reclose or reset condition. Conductors in close proximity to one another (i.e., incoming and outgoing cables in a feed-thru transformer, junctions, spacer cable, or underbuilt circuits) can influence the sensing ability of the FCI. In addition, fault current in a phase conductor can be reduced by opposite flowing fault current in the respective neutral conductor. Depending on the placement of the FCI, close proximity could affect a proper trip or reset response. Need Diagram 5.4.1.4 Proximity Energy The influence of energy from adjacent conductors or circuits on the operation of a FCI is known as Proximity Effect. The effect can occur in a number of different ways. Multi-phase circuit conductors could be very close together. The close proximity of the conductors can make it difficult for FCIs to properly distinguish between the various energy fields generated during a fault, reclose or reset condition. Conductors in close proximity to one another (i.e., incoming and outgoing cables in a feed-thru transformer, junctions, spacer cable, or underbuilt circuits) can influence the sensing ability of the FCI. In addition, fault current in a phase conductor can be reduced by opposite flowing fault current in the respective neutral conductor. Depending on the placement of the FCI, close proximity could affect a proper trip or reset response. Need Diagram typicalorientation adjacentcable distance DEFINITION: Proximity Energy 5.4.1.5 Delta connections In other situations, such as isolated overhead circuits that serve three-phase underground taps having single-phase protective devices, feedback current can be generated through any delta connected load that remains connected to a grounded wye-grounded wye transformer after a fault occurs. This current could be sufficient to false trip or to incorrectly reset an FCI, which was previously tripped. See Figure 7. Figure 7 – Delta connected loads “Electric Power Distribution Handbook” Burke “Electric Power Distribution Handbook Burke” Transformer Connection Primary Secondary Load Connection Possible Backfeed Yes Yes No No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Backfeed can occur with these transformer/Load connections when used with single phase protection. 5.4.1.6 Multi-legged Transformers In a similar situation, when FCIs are installed on multi-legged core transformers, circulating current within the transformer may be of sufficient magnitude to reset a tripped FCI. 5.4.1.7 Installation of faulted circuit indicators on parallel cable circuits FCIs that are installed on parallel feeder cables can give false indications of the fault location. See Figure 6. When a fault occurs on a parallel cable run, fault current will flow in both cables. Each FCI on both ends of the parallel cable run will trip indicating a fault. This situation may lead to the conclusion that the fault occurred in the next downstream cable run. Flow of Fault Current Figure 8 – Parallel Cable Circuits FCIs Indicating Fault 5.4.1.6 Multi-legged Transformers In a similar situation, when FCIs are installed on multi-legged core transformers, circulating current within the transformer may be of sufficient magnitude to reset a tripped FCI. 5.4.1.8 Directional FCIs Directional FCIs can be used to identify which cable of a parallel cable circuit is faulted. See Figure 9. When each FCI at the source end of the parallel cable circuit indicate a fault condition in the same direction the fault is located beyond this point. If the FCIs located at the load end of the parallel cable circuit indicate a fault in opposite directions, the fault is toward the source. Opposite Pointing FCIs Indicate Fault is on This Cable Section Source Load Flow of Fault Current Figure 9– Directional FCIs Opposite Pointing FCIs Indicate Fault Is Toward Source 5.4.1.9 Backfeed Voltage (This needs input and clarification) Backfeed voltage can cause voltage resetting FCIs to incorrectly reset. FCIs located on three-phase circuits with single-phase protection and delta-connected loads are susceptible to this type of situation. Under these circuit conditions the backfeed voltage could be sufficient to cause an FCI to reset. 5.4.1.10 Distributed Generation Distributed generation can be a source of both current and voltage. When Distributed Generation is connected to the circuit beyond the fault, they may provide sufficient current to trip FCIs that are located between the fault and the generator. Generators that do not isolate themselves from the faulted circuit quickly enough may also provide voltage sufficient to reset a voltage reset FCI. The actual effects of distributed generators depend on the sizes of the generator(s) and the interconnection/protection requirements of the utility. 6. Other considerations Annex A (informative) Application Information 1. The typical application of FCIs to 200 / 600 A, distribution circuits is summarized as follows: 2. Pick a trip level of less than 50% of the available fault current or 500 amperes, whichever is less. 3. Ignore inrush, except on very long or heavily loaded laterals. In cases where inrush is a problem, use inrush restraint. 4. Use a fault impedance of 0 to 2 ohms when calculating fault currents. 5. Ignore “high impedance” faults since they are undetectable with FCIs. 6. Ignore “cold load pickup” when using automatic resetting FCIs. 7. For current resettable devices, select the device with the lowest reset current available. 8. Use voltage reset or time reset where load currents are low (e.g., 25 kVA transformer on a 34.5 kV system). 9. Select a display method that enhances operating practices. 10.Coordinate FCIs with inrush current and protective devices. 11.Place the FCIs on outgoing cables. Annex B (informative) Bibliography [B1] “Application of Fault Indicators on the Con Edison Electrical Distribution System”, J. P. DiDonato, EEI T&D Meeting, May 17, 1989. [B2] “Characteristics of Distribution Systems That May Affect Faulted Circuit Indicators,” J. J. Burke. [B3] “Characteristics of Fault Currents on Distribution Systems”, J. J. Burke, D. J. Lawrence, IEEE Transactions on Power Apparatus and Systems, Vol. PAS-103, No. 1. January 1984, pages 1-6. [B4] Electric Power Research Institute Report EL-3085, Distribution Fault Current Analysis, May 1983 [B5] “Fault Indicator Applications at Virginia Power Company”, T. E. Royster, 1991 IEEE/PES T&D Conference and Exposition. [B6] “Fault Indicator Types, Strengths & Applications”, F. J. Muench, Jr., G. A. Wright, IEEE Transactions on Power Apparatus & Systems, Vol. PAS-103, No. 12, December 1984, pages 36883693. [B7] IEEE 100, “The Authoritative Dictionary of IEEE Standards Terms”, Seventh Edition. Fall 20112 – St. Petersburg, FL November 11-14, 2012 at the Tradewinds