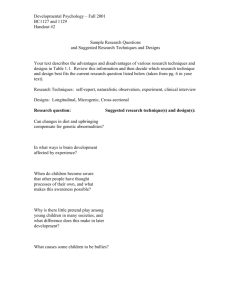

art and function in the law of copyright and designs

advertisement