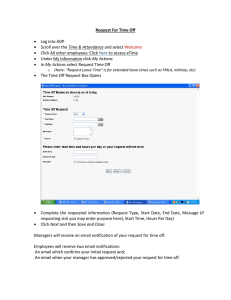

Evaluation Report

advertisement