Justifiable Homicide 1 Running Head: Justifiable Homicide

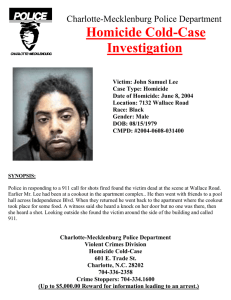

advertisement

Justifiable Homicide Running Head: Justifiable Homicide Justifiable Homicide in Criminal Justice Student 3 Minnesota State University Mankato 1 Justifiable Homicide 2 Abstract In the article, “Justifiable Homicide by Police Officers,” Gerald D. Robin states that innocent homicide is defined as either 1) a justifiable homicide commanded or authorized by law; or an excusable homicide, which is in self-defense or unintentional or 2) a justifiable homicide which in context with common law terms is a reference to the killing of an offender by a police officer or another agent of the law . In his study on justifiable homicide, published in 1963 Gerald Robin focused on the statistical aspect and impact of police shootings rather than looking at social reasons or possible deterrents or solutions. Justifiable homicide in criminal justice is unique in the sense that the perpetrator is both an offender and a victim as their death is a result of their unlawful behavior. As Robin states “There can be little doubt that for the V-O’s (victim-offenders)…crime doesn’t pay” (1963). In his article Robin uses information gathered from 1950 through 1960 in Philadelphia on justifiable homicide by police officers as well as data pulled from the National Office of Vital Statistics reports on the numbers of criminals killed by police officers, and information gathered from eight other cities during the same time period. To better understand justifiable homicide you must first look at the use of deadly force and when it is acceptable. Siegel & Senna (2008) found that the use of deadly force is derived from common law where many offenses were felonies and therefore punishable by death, the use of deadly force was acceptable when apprehending a felon in those days because their death would save the state the trouble and time of a trial. Today deadly force is still justifiable when attempting to Justifiable Homicide 3 apprehend a felon if that is your only means of stopping them, or if an offender becomes assaultive in a manner likely to cause bodily harm or death of the officer (Siegel & Senna, 2008). An officer cannot use deadly force on a fleeing suspect if they only have suspicion that they committed a felony, to use justifiable deadly force they must either know they suspect is a wanted felon or have witnessed them commit a felony. Robin (1963) found that in certain states courts have ruled that deadly force can be used while arresting a misdemeanor offender only if they become assaultive, otherwise non-lethal force must be used. Police violence and shootings have made headline news for decades now, but the perception that it is wide-spread is based on fiction and news blown out of proportion. Robin’s article found that during the 1950’s the number of justifiable police homicides (JPH’s) nationwide never exceeded 282 well staying in the 226 and 282 range (Robin, 1963). Even today the numbers are between 250 and 300 annually (Siegel & Senna, 2008) although some researchers believe these numbers are low due to misreporting or coroner mistakes. Although these numbers may appear high they must be taken in perspective to overall population, according to statistics the ratio of JPH’s in the nine cities responding to the survey they varied from only as high as 7.06 in Miami to as low as .4 per one million citizens in Boston during the 1950-1960 timeframe (Robin, 1963). In the Philadelphia study a closer look was taken at who the V-O’s were and why they became victims of justifiable police homicide. Racial profiling has been a problem in the criminal justice system for years, when it comes to JPH”s it’s no different story. Robin (1963) has found that in Philadelphia the ratio of African- Justifiable Homicide 4 Americans killed compared to whites in JPH cases was 21.9 to 1 in the 1950’s, among the other eight cities surveyed the ratio was as high as 29.5 to 1 in Milwaukee. Sociologist Paul Takagi said that when it comes to police officers they have “one trigger finger for whites and another for African Americans “(Siegel & Senna, 2008). Researcher James Fyfe had a different outlook on race and JPH’s; he found during a five-year study of JPH’s in New York City that AfricanAmerican officers were almost twice as likely to shoot a citizen as white officers were ( Siegel & Senna, 2008). Fyfe attributes this to the fact that many African- Americans live and work in high-crime areas thus leaving them more open to violence. The study conducted in Philadelphia also looked at past criminal records of V-O’s and what crimes they were committing at the time of their deaths. Twenty-four of the thirty-two V-O’s were in the process of committing a Part 1 offense at the time well the remaining eight became violent leading to their deaths even though they only committed misdemeanor offenses(Robin, 1963). In addition twenty-five resisted arrest, while the remaining seven fled; a vast majority had multiple previous arrests for crimes against people as well (Robin, 1963). Another trait of V-O’s is their mental health at the time of their death, from 1988-1998 almost one in ten V-O’s in Los Angeles were suicidal and provoked officers into shooting them (Siegel & Senna, 2008). Although research has shown that police officers in the line of duty are not at an extreme risk of injury or death, in fact only 33 in 100,000 dies on the job every year (Robin, 1963) including deaths in traffic accidents, but when coupled with workload of the officer, environment and actions of the offender it is almost always “clear that criminals killed by police are….responsible for their own death “Robin (1963). Justifiable Homicide 5 Senna, Joseph J., & Larry J. Siegel. Study Guide for Siegel/Senna's Introduction to Criminal Justice, 11th Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing, 2007. Robin, Gerald D. Justifiable Homicide by Police Officers, in The Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology, and Police Science (Volume 52, Number 2, 1963) Northwest University