Introduction to San José State University’s Educational Effectiveness Report Introduction

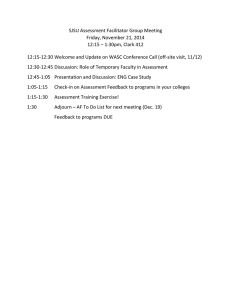

advertisement