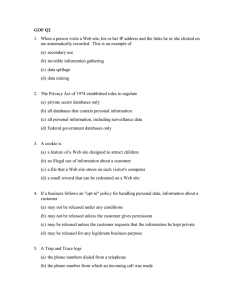

1 Copyright (c) 2007 Northwestern University, School of Law

advertisement