Civil Disaster:

advertisement

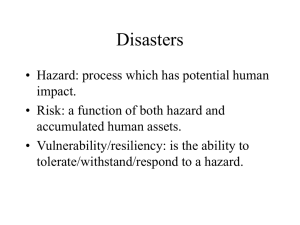

Civil Disaster: The Risk of Civil War in the Wake of Natural Disaster Over time, natural disasters are gradually increasing in intensity, injuring, killing, and displacing millions of people each year, while simultaneously causing billions of U.S. dollars in damages. However, could natural disasters also be increasing the probability of civil war within the countries that they affect? Could natural disasters be increasing the intensity of pre-existing civil wars? If so, what types of countries could be the most susceptible? The findings of this study demonstrate that the number of natural disasters that occur in a country per year directly increase the risk of rapid onset civil war within that country, though they do not increase the intensity of pre-existing civil wars. Additionally, as the number and severity of natural disasters in the memory of a country’s population increase, the likelihood of a civil war onset in the current year increase as well. Eric Jones International Relations Honors Thesis New York University Spring 2014 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the following individuals for their assistance in the undertaking of this research study: Mr. Kaivan Sattar, for his contributions to the theory and empirical design behind this paper, and for volunteering his time to educate this author in the methods of enhanced research Dr. Alastair Smith, for his assistance and guidance from the inception of the idea that led to this study to its final stages of development Mr. Benjamin Pasquale, for helping to create the dataset on which this study is based My fellow classmates, for their questions and constructive criticisms throughout the writing process 3 Introduction While the average annual natural disaster frequency has decreased in recent years, the value of economic damages is increasing significantly each year. Global climate change experts predict that as world temperatures increase, natural disasters around the world will continue to grow in strength, causing more and more damage with the passage of time. Natural disasters destroy infrastructure and livelihoods while displacing, injuring, and killing millions. Many governments around the world are not equipped or not willing to adequately respond in the wake of a serious natural disaster, often leaving citizens to find alternate ways to survive. This thesis will examine the effect of natural disasters on the onset of civil war, as well as how they affect the intensity level of pre-existing conflicts. I find that as the annual number of natural disasters increases, the risk of the rapid onset of civil war within the affected country increases as well. Countries face an additional risk of civil war if they are relatively large, democratic, fractionalized by ethnicity and language, and/or face economic stagnation or decline. Natural disasters create severe resource scarcity within the affected regions of countries in these categories, inciting competition for their control. The struggle for resource control can lead to organized factions (sometimes along ethnic and linguistic lines) that assert their control through force. Destruction of property and infrastructure, coupled with an ineffective response by the country’s government, can lead these groups to violently oppose the nation’s leadership, erupting in civil war. The potential combatant labor supply for both the government and the opposition will increase as the economic situation worsens in the aftermath of natural disaster. Natural 4 disasters also open the door for opportunistic opposition groups to rise up and grab power from crippled governments. Additionally, this study concludes that a country’s population tends to remember natural disasters and their severity from the previous 10 years; this memory of hardship and accumulated discontent leads to a significant increase in the probability of civil war within that nation. While the quantity of natural disasters, both in the observed year and in years past, significantly increases a country’s risk of intrastate conflict, natural disasters that strike during an ongoing civil war neither intensify nor de-escalate the conflict. Proposed Questions Given the lack of a general consensus among scholars on the relationship between natural disasters and civil war, this study seeks to answer the following questions: 1) Do natural disasters (e.g. earthquakes, hurricanes, droughts, tsunamis, etc.) have a significant effect on the probability of the rapid onset of civil war within their affected countries? 2) Does the memory of past natural disasters increase the probability of civil war within a country? 3) Do natural disasters intensify or de-escalate the level of violence within an affected country, if that country is engaged in a pre-existing civil conflict. 5 Within this study, the term natural disaster refers to a “natural process or phenomenon that may cause loss of life, injury or other health impacts, property damage, loss of livelihoods and services, social and economic disruption, or environmental damage.”1 Given this definition of a natural disaster, the subsequent analysis will focus on the total number of individuals affected by natural disaster per-capita; this variable encompasses the largest number of effects that a natural disaster can cause in a given country (including the number of people who are injured, require immediate assistance, and those who are left homeless).2 The definition of a civil war varies from scholar to scholar and is not explicitly defined by the United Nations. James Fearon defines civil war as “a violent conflict within a country fought by organized groups that aim to take power at the center or in a region, or to change government policies.”3 The term civil war will refer to Fearon’s definition of a civil war, with the added provision that at least 25 battle-related deaths occur per calendar year; this is the numerical threshold used by the International Peace Research Institute, Oslo (PRIO), which is the source of this study’s conflict-related data. I will examine the occurrence or non-occurrence of a civil war the first dependent variable in this study, as well as the annual battle deaths per 10,000 people living in a country as the second dependent variable. When coupled with the instance of a natural disaster, there are other key independent variables that are interesting to observe. I will examine the possibility that a country’s regime type can have an added effect on the probability of the onset of a civil war, as well as on a pre- 1 "Terminology." United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. United Nations, 30 Aug. 2007. Web. 4 Feb. 2014. 2 "EM-DAT Glossary." Emdat.be. Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters, 2009. Web. 1 Apr. 2014. 3 Fearon, James D. "Iraq's Civil War." Foreign Affairs 86.2 (2007): 2-15. JSTOR. Web. 4 Feb. 2014. 6 existing conflict’s intensity. Due to the prevalence of ethnic, linguistic, and religious divisions within civil wars, I will also analyze the impact of ethno-linguistic fractionalization (ELF) within affected countries. Larger countries have a greater chance of including many of these diverse groups and include more individuals that may become discontented, therefore making the population size of a country another important point of analysis. Annual percent growth in GDP per-capita will also be examined, as the health of a country’s economy is a widely accepted indicator of the risk or non-risk of violent civil conflict. Global Climate Change & Natural Disasters One of many unsettling disaster statistics from the year 2012 was a record-setting US$ 157.3 billion of damages caused by natural disasters around the world.4 Three-hundred fiftyseven reported natural disasters killed almost 10,000 people worldwide, affecting more than 122 million individuals.5 Generally, the Asian Pacific and Oceania are the most heavily affected parts of the world. Asian countries account for 53.4% of natural disaster related deaths reported in 2012, while Pacific Island nations tend to rank in the top 10 in mortalities per-capita.6 However, African nations account for seven of the top 10 nations in terms of the total number of people affected as a proportion of the total population due to consistent droughts and famines that affect large parts of the continent.7 It is a common misconception among nationals of the world’s most prosperous countries that natural disasters overwhelmingly affect the citizens of third-world nations. Five of the top 10 countries ranked by disaster mortality fit into the World 4 Guha-Sapir, Debarati, Philippe Hoyois, and Regina Below. .Reliefweb.int. Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters, Aug. 2013. Web. 20 Mar. 2014. 5 Guha- Sapir, et al. 6 Guha- Sapir, et al. 7 Guha- Sapir, et al. 7 Bank classification of ‘high-income’ or ‘upper-middle income’ economies;8 these countries contributed 45.7% of reported fatalities from natural disasters in 2012.9 In the United States, Hurricane Sandy alone caused damages estimated to be US$ 50 billion, while the United States endured US$ 98.5 billion in total damages.10 Graph 1: Total Number of Natural Disasters Reported (1900 – 2010)11 Graph 1 demonstrates the rapid escalation of the number of reported natural disasters until about 2000, from which point the world has experienced a gradual decline, on average. The 8 "Country and Lending Groups." Worldbank.org. The World Bank, n.d. Web. 23 Mar. 2014. Guha- Sapir, et al. 10 Guha- Sapir, et al. 11 EM-DAT: The OFDA/CRED International Disaster Database – www.emdat.be - Université catholique de Louvain – Brussels – Belgium. 9 8 decline in the total number of natural disasters would lead some to believe that the global population has been less affected by natural disasters in the years following the second millennium. However, Graph 2 (below) tells a different story: Graph 2: Total Number of People Reported Affected by Natural Disasters (1900 – 2011)12 The graph makes it clear that despite the fact that natural disasters have been decreasing in number since 2000, the number of people affected by natural disasters has continued to rise. One may interpret this phenomenon in the following way: natural disasters are increasing in their intensity each year. EM-DAT: The OFDA/CRED International Disaster Database – www.emdat.be - Université catholique de Louvain – Brussels – Belgium. 12 9 Literature Review The literature on the link between natural disasters and violent civil war is very inconsistent. Among the existing studies, four different conclusions are prevalent: 1) Climaterelated natural disasters decrease the risk of the onset of civil war in their affected countries; 2) Climate-related natural disasters do not increase the risk of civil war; 3) Earthquakes increase the risk of intrastate conflict in their affected countries; and 4) Natural disasters increase the risk of civil war. The following is a brief summary of the studies that contributed these conclusions to the field. Inspired by the growing relevance of the issue of global climate change, a study by Rune T. Slettebak, conducted in 2012, determined that climate-related natural disasters lower the risk of civil war in the countries that they affect based on data from 1946 - 2008.13 The study uses an existing model developed by Fearon & Laitin (2003), which was modified in order to test how climate-related natural disasters affect the likelihood of civil war, as Slettebak believed that this model was well-tested and included independent variables that would act as relevant controls. His data on natural disasters comes from the EM-DAT database (2007), while his civil war onset data comes from the UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset (2006); other sources of data include The Penn World Tables (2009), World Bank (2007), the Correlates of War Project (2008), and the Polity IV Project (2009). The findings of his study conflict with much of the research that preceded the paper; however, Slettebak does mention that they are consistent with sociological 13 Slettebak, Rune T. "Don't Blame the Weather! Climate-Related Natural Disasters and Civil Conflict." Jpr.sagepub.com. SAGE Journals, 31 Jan. 2012. Web. 23 Nov. 2013. 10 research from the 1950s and 1960s, which indicated, “anti-social behavior tends to drop during and after disasters.”14 Drago Bergholt and Päivi Lujala conducted another study in 2012 that focused solely on natural disasters caused by the climate.15 They conclude that, while frequent and severe natural disasters negatively affect the GDP growth-rate of affected countries, this effect on the GDP growth-rate does not, in turn, lead to more civil wars through its effects. Their study differs because it tests the risk of civil war through the effects that natural disasters have on economic variables (specifically real GDP per-capita growth-rate). Using observations from 1980 – 2007, Bergholt and Lujala’s data comes from Penn World Table (2009), the UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset (2010), the EM-DAT (2012), and the United Nations Statistical Data (2010). The results regarding civil war onset are ultimately insignificant; however, the range of countryyear observations was relatively small (only 27), and the study focused only on climate-related natural disasters and their affects on civil war through their negative effects on a country’s economy. While the previously discussed studies focused only on climate-related natural disasters, this 2007 study conducted by Dawn Brancati narrows the scope even further by focusing only on earthquakes.16 She concludes that earthquakes increase the risk of civil war through producing extreme resource scarcity. The risk would be even higher “in developing countries where the 14 Slettebak, p. 164 Bergholt, Drago, and Päivi Lujala. "Climate-Related Natural Disasters, Economic Growth, and Armed Civil Conflict." Journal of Peace Research 49.1 (2012): 147-62. No Records. Web. 17 Feb. 2014. 16 Brancati, Dawn. "Political Aftershocks: The Impact of Earthquakes on Intrastate Conflict." Journal of Conflict Resolution 51.5 (2007): 715-43.Http://brancati.wustl.edu/. 2007. Web. 22 Nov. 2013. 15 11 competition for scarce resources is most intense.”17 Earthquakes of higher magnitudes have a greater effect, especially when they occur in poor countries that are densely populated. Brancati seems to be the only study not to use the EM-DAT for natural disaster statistics, instead using the Centennial Earthquake Catalog data (Engdahl and Villasenor, 2002),18 which indicates earthquake magnitudes and epicenters, in addition to ArcMap (Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc.) and the CIA’s World Factbook (2007). Her dependent variables on conflict come from various sources, such as the IDEA events dataset (2003) and the MAR dataset (2005),19 while her controls for economic status and regime type come from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators (2007) and the Polity IV Project (2006), respectively. Despite being the most specific/limited study I reviewed in terms of natural disaster types, Brancati’s dataset appeared to be the most meticulously constructed, likely due to its focus on a single natural disaster type. A 2008 study conducted by Philip Nel and Marjolein Righarts found that natural disasters, both climate-related and independent of climate (earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, etc.) significantly increase the risk of violent civil conflict, both in the short and medium term. They assert that natural disasters increase the risk of civil war in the short and medium terms through the testing of a variable called brevity of peace, which measures a society’s predisposition for conflict over time. Furthermore, Nel & Righarts asserted that “rapid-onset disasters related to geology and climate pose the highest overall risk.”20 Their data is obtained from the UPPSALA/PRIO dataset on domestic armed conflict, the EM-DAT, the World Bank, the 17 Brancati, p. 715 Brancati, p.726 19 Brancati, p. 727 20 Nel, Philip, and Marjolein Righarts. "Natural Disasters and the Risk of Violent Civil Conflict." International Studies Quarterly 52 (2008): 159-85. www2.comm.niu.edu. 2008. Web. 22 Nov. 2013. 18 12 Estimated Household Income Inequality dataset from the University of Texas Inequality Project, and the Polity IV Project, with country-year observations from 1950 to 2000. Each of the studies discussed in this section have obvious merits and adequately evaluate the hypotheses that they proposed. However, none of them definitively answer each of the questions that I seek to answer through the course of this study. Theory and Mechanisms My inspiration for choosing to explore these questions came from a project that my work taskforce was assigned to during the summer of 2013. The focal point of my analysis was the Republic of Dagestan, located in the Russian North Caucasus region. Since the 1999 invasion by the Chechnya-based Islamic International Brigade during the Second Chechen War, Dagestan has suffered a low-level, but pervasive (and more recently, escalating) insurgency led by Salafist militants tied to the Caucasus Emirate terrorist organization. My analysis of this insurgency focused heavily on Russian, Dagestani, pan-Caucasus, and jihadi traditional media, social media, and other user-generated content. I recorded every reported act of violence associated with or attributed to the insurgency, as well as general acts of violence, and kept a tally of all deaths resulting from these instances. I then overlaid every act of violence/death onto a map of Dagestan, color-coding them based on the type of attack (e.g. shootings, bombings, brawls, suicide-bombings, etc.). 13 Dagestan is very ethnically diverse, and upwards of 30 languages are spoken in the republic. Certain ethnic groups are more prone to living in cities, while others are more tied to agriculture and animal herding. Every summer (typically during the months of May, June, and July), the ethnic groups who produce the vast majority of Dagestan’s agricultural products are plagued by large locust swarms. The locusts arrive suddenly in swarms, destroy massive amounts of crops, and then disappear. The livelihoods of these farmers and, to an extent, animal herders, are unexpectedly gone without enough time to be adequately replaced before the upcoming harvest season. During the summer of 2013, there were a few particularly devastating locust swarms in Dagestan and the surrounding republics. In the weeks and months following these swarms, I noticed that the number of violent acts associated with the insurgency escalated, especially shootings and bombings. In the case that a suspect was identified in the attack, he was often described in the media as a man belonging to the ethnic group typically found in the agricultural regions of the republic. Therefore, I made the connection that it could be possible that the men who lost their sources of income during the locust swarms turned to the Caucasus Emirate’s insurgency as a way of providing for themselves and their families. While this connection was not tested through statistical analysis, it was enough to prompt me to consider the theory that natural disasters could affect the probability of the onset of civil war and the intensity of preexisting conflict within a country. Question 1: Do natural disasters have a significant effect on the probability of the rapid onset of civil war within their affected countries? 14 Natural disasters upset the order of affected countries, creating a certain level of unpreventable chaos. A natural disaster can destroy the livelihoods of thousands of individuals, especially in less developed nations and agrarian economies where the infrastructure to prevent damage on a massive scale does not exist. The lack of adequate infrastructure leads to intense competition for a limited number of resources by the affected population. The highest levels of competition will revolve around essential resources (e.g. food, water, shelter, medicine, relief aid), which become scarce after the natural disaster. In order to survive, individuals would be inclined to fight for these scarce, essential resources, leading to civil war. The likelihood of conflict would probably be higher in underdeveloped countries, where more low-income individuals would be affected, the damage would be greater, and the local government would be less capable of preventing conflict through non-violent measures. One concrete example of where the devastating impact of a natural disaster led to the onset of civil war can be found in the 1970 cyclone that hit East Pakistan, which the Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance of the United States Agency for International Development claims “evolved into a civil war [Bangladesh Liberation War], intervention by India, and the subsequent creation of Bangladesh.”21 Approximately 85 percent of homes within the affected area of East Pakistan were destroyed, and the West Pakistan government was slow to respond with supplies and disaster relief efforts due to the East’s anti-West sentiment.22 21 United States of America. United States Agency for International Development. The Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance. A Critical Juncture Analysis, 1964-2003. By Richard S. Olson. Miami: Florida International University, 2005. 22 "The Great Bhola Cyclone." Geol105naturalhazards.voices.wooster.edu. The College of Wooster, 23 Oct. 2012. Web. 25 Mar. 2014. 15 Four mechanisms could connect natural disasters and civil war: 1) Resource scarcity, 2) Ineffective government response, 3) Increased combatant labor supply, and 4) Opportunism of government opposition groups. These mechanisms are not mutually exclusive and frequently occur in conjunction with each other. Each mechanism is more likely to lead to conflict if the affected country is impoverished. The third mechanism is most relevant when considering preexisting conflicts. Scholars and international organizations agree that resource scarcity leads to conflict. John W. Maxwell and Rafael Reuveny argue that conflict over scarce, renewable resources is becoming more frequent, especially in developing countries, and that the conflict occurs cyclically.23 Their model suggests that the relationship between resource scarcity and conflict is bidirectional; conflict can also cause resource scarcity. However, for the purposes of this study, the bidirectional relationship between resource scarcity and conflict will not affect the results, as natural disasters directly cause resource scarcity. Even if a conflict is pre-existing and already caused a degree of resource scarcity, a natural disaster would exacerbate the scarcity further. A natural disaster will either cause or increase the severity of resource scarcity, forcing individuals to compete for resources to survive. In theory, this competition will trigger organized conflict, or intensify pre-existing conflict, within a state. Resource scarcity is more likely to occur if the affected country is poor because there are fewer resources to begin with, individually and collectively. 23 Maxwell, John W., and Rafael Reuveny. "Resource Scarcity and Conflict in Developing Countries." Journal of Peace Research 37.3 (2000): 301-22. JSTOR. Web. 10 Dec. 2013. 16 When a natural disaster strikes a developed country, like the United States, the government has the infrastructure and resources to respond appropriately and provide aid/relief to the affected country and individuals (e.g. FEMA in the U.S.). In contrast, when a natural disaster strikes an underdeveloped country, or a region of a country that is underdeveloped, that capability to respond to the crisis is significantly lower or sometimes non-existent. For example, the typhoon that recently affected the Philippines, Typhoon Haiyan, caused a significant amount of casualties and property damage due to the poor infrastructure in many of the affected countries. The government of the Philippines lacks the resources to quickly remedy the situation, so it relies on foreign countries to provide aid and assist with relief efforts. While this response is limited, it is at least more significant than that of the nonexistent response by the Russian government to the aforementioned decimated crops in Dagestan. Little to no aid/relief provision by a government to affected citizens leads to disenfranchised individuals seeking income and security; this can lead to actions such as looting, which can escalate into organized conflict. A government that is unable to provide aid is a government that is unlikely to peacefully suppress rebellion. Once groups are mobilized, such a government could struggle to end a violent rebellion. Alternatively, an autocratic/mixed government with a small selectorate could potentially lack the motivation to provide aid/relief to an area within its state after a natural disaster. If a rebellion were to commence in the wake of a natural disaster this type of a regime, the likelihood of a violent government crackdown would be quite high, given the lack of accountability that the government has to its citizens in such a political system. Regardless of a government’s regime type, in the aftermath of a severe natural disaster, the capacity of the federal government is 17 generally weakened; hypothetically, this provides potentially violent government opposition groups with the ideal situation in which to seize power from the government by force. Question 2: Does the memory of past natural disasters increase the probability of civil war within a country? My study will define a population’s memory of past natural disasters through the interaction between the number of disasters per year and the number of people affected by natural disaster each year per capita summed over the past 10 years. The variable used to test the significance of the population’s memory will be known throughout this study as the cumulative misery threshold (CMT).24 Whereas Nel & Righarts measured the significance of natural disasters on the risk of civil war over time using the brevity of peace variable, which measured “the conflict proneness of a society over time,”25 my study seeks to measure how the accumulation of natural disaster related ‘misery’ over time affects the likelihood of civil war onset in the present year. The goal is to establish a significant boiling point (threshold) where the population of a country can no longer endure the misery induced by the negative effects of natural disasters, causing them to rebel violently in order to change their circumstances. Question 3: Furthermore, do natural disasters intensify the level of violence in affected countries with pre-existing civil war? 24 A more in-depth description of the CMT may be found later in this paper, within the Empirical Research Design section. 25 Nel & Righarts, p. 178 18 In the opinion of this study, no existing scholarly work adequately answers this question. My study will seek to answer the intensity question through the analysis of battle deaths resulting from civil wars. The main theoretical mechanism that could contribute to the level of intensity is the increase in the available combatant labor supply in the wake of natural disaster. When a natural disaster destroys one’s livelihood, one suddenly loses all sources of income and has no way of providing for oneself or one’s family. In an area with pre-existing civil war, such as a civil war, an insurgency, or high levels of terrorist activity, the option exists for this individual to join a faction participating in the conflict in order to gain income, shelter, food, protection, etc. For example, if a severe drought strikes agricultural Sri Lanka, many farmers would lose their crops and the harvest would not yield enough product for the farmers to earn a living wage. There would then be a large increase in the labor supply within that area. Some of these individuals could be tempted to join the local insurgent group, the LTTE (Tamil Tigers), as a means of earning income and supporting themselves/their families. The combatant labor supply increases after a natural disaster strikes because the resulting damage leaves many individuals without a source of income. When this scenario is applied to a natural disaster that affects thousands of individuals, even if only a fraction of those affected end up participating in the conflict, the labor supply of combatants is bolstered significantly. In turn, this will intensify the conflict and increase the number of violent acts carried out within the state in question. 19 Overall, the relevant actors are the individuals who are directly affected by the natural disaster. These individuals are most likely poor and will do what is necessary to acquire resources necessary for their survival, even if that means resorting to violence against other groups of poor individuals or the government. I expect them to form groups or join pre-existing groups in order to ensure their survival and increase their chances of resource acquisition; this will either initiate violent conflict or intensify ongoing conflict. A lack of responsiveness or an ineffective response to the disaster by the government can either cause or exacerbate the need for individuals to mobilize. A government that meets a rebellion with force will intensify the violence. Hypotheses Within this study, I will test the following hypotheses: H1: When the annual number of natural disasters increases within a given country-year, the risk of the rapid onset of civil war will increase; this probability is greater when: H1a: The affected country is governed by a regime that is more autocratic than democratic; H1b: The affected country has high ethno-linguistic fractionalization (ELF); H1c: The affected country has a large population size; H1d: The affected country has stagnant or negative GDP per-capita growth; H1e: The natural disaster affects a greater proportion of the population; 20 H2: In a given country, as the number and severity of natural disasters in the recent past increases, the risk of civil war will increase as well; this probability is greater when: H2a: The affected country is governed by a regime that is more autocratic than democratic; H2b: The affected country has high ethno-linguistic fractionalization (ELF); H2c: The affected country has a large population size; H2d: The affected country has a low GDP per-capita; H2d: The affected country has stagnant or negative GDP per-capita growth; H2e: The natural disaster affects a greater proportion of the population. H3: The occurrence of a natural disaster or natural disasters within a country where there is a pre-existing civil war will intensify the severity of that conflict; this intensity is greater when: H3a: The affected country is governed by a regime that is more autocratic than democratic; H3b: The affected country has high ethno-linguistic fractionalization (ELF); H3c: The affected country has a large population size; H3d: The affected country has stagnant or negative GDP per-capita growth; H3e: The natural disaster affects a greater proportion of the population. 21 Data Description I began my data collection with the Center for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters’ (CRED) Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT).26 The EM-DAT was created in 1988 with support from the World Health Organization and the Belgian government. Current up until the end of 2013, the EM-DAT contains data on over 18,000 natural and technological disasters since 1900, including their occurrence, affected countries, and their effects. Each disaster included in the dataset meets one of more of the following criteria: 10 or more people were killed, 100 or more people were affected, a state of emergency was declared, and/or there was a call for international assistance. Data in the EM-DAT is acquired from many sources, including the United Nations, non-governmental organizations, insurance companies, research institutes, and press agencies. The EM-DAT is made publically accessible through an advanced search feature on their website, allowing one to filter their data by time, location, and type of disaster. For this study, I used the EM-DAT data from 1950-2008, globally, including all natural disaster sub-groups (biological, climatological, geophysical, hydrological, and meteorological). I aggregated the data by country and year. My data includes three variables generated from the variables of the EM-DAT, as well as a number of lagged variables based on the original data. I added both the natural logarithm of the number of natural disasters per year and the natural logarithm of the number of people affected, per-capita, per year. Dividing the number of people affected by the population of the country captures the relative impact that disasters had in a country that year. For example, it 26 EM-DAT: The OFDA/CRED International Disaster Database – www.emdat.be - Université catholique de Louvain – Brussels – Belgium. 22 would be a significant error to compare the impact of natural disasters affecting 50,000 people in a large country like Brazil versus a small country like Cuba. The third variable created using the EM-DAT data is an interaction variable (hereon referred to as disaster/affected) between the two previous variables, as they are closely tied to each other. I lagged the logged number of natural disasters per year for each of the 10 years prior to any given observation; the same was done for disaster/affected. All of my conflict-related data comes from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP)/International Peace Research Institute, Oslo (PRIO) Battle Deaths Dataset (1946-2008) Version 3.0.27 Key variables include the annual battle deaths (best estimate), the conflict start date, and the conflict end date. The UCDP/PRIO originally included four types of conflict: extrasystemic, interstate, intrastate, and internationalized internal. As I am only interested in the onset and intensity of civil war, I removed all observations coded as extrasystemic, interstate, and internationalized internal. I chose to exclude the conflict type internationalized internal (conflict between the government of a state and one or more domestic opposition groups with intervention by other states) because it included many observations that were not truly civil wars, such as all U.S. battle fatalities that resulted from the War on Terror in Afghanistan and Iraq. To make the UCDP/PRIO dataset more complete, I added two additional variables. First, I added a variable representing the number of annual battle deaths per 10,000 people living in a country. Scaling the variable in this manner increased the relative size of my resulting coefficients, making them easier to interpret. Second, I created a dummy variable for all years 1950-2008 that indicates whether or not a civil war occurred in a given nation-year. Battle deaths per 10,000 Lacina, Bethany & Nils Petter Gleditsch, 2005. ‘Monitoring Trends in Global Combat: A New Dataset of Battle Deaths’, European Journal of Population 21(2–3): 145–166. 27 23 people is the dependent variable used to measure the intensity of civil war (hypothesis 3), and the civil war dummy variable is the dependent variable used to test the onset of civil war (hypotheses 1 & 2). To supplement the EM-DAT and UCDP/PRIO datasets, I added select independent variables that were likely to affect the probability of the onset/intensity of civil war. My variables related to ethno-linguistic fractionalization were taken from the dataset created for and used in the 2003 paper entitled “Fractionalization,” written by Alesina, Devleeschauwer, Easterly, Kurlat, and Warcziarg.28 Their data on language and religion dates to 2001, but much of the data used to calculate the ethnic fractionalization index is from the 1990s. Most of the data originated from national censuses, covering 215 countries. In my dataset, I use the ethnic, linguistic, and religious fractionalization indices from the “Fractionalization” dataset. However, because the index scores for each country are only available for a single year, and there is no dataset that has the index scores for a range of years, I had to apply the single score from each country to all nation-years (1950-2008). Alesina, et al. measured levels of fractionalization using a scale from 0 to 1, where 0 is the least fractionalized and 1 is the most fractionalized. From the Polity IV Project (Marshall, Gurr, & Jaggers),29 I incorporated the polity scores of each country. Since polity scores range from -10 (most autocratic) to +10 (most democratic), I created a new variable scaling the scores from 0 to 1 in order to simplify their analysis. Using 28 Alesina, Alberto, Arnaud Devleeschauwer, William Easterly, Sergio Kurlat, and Romain Wacziarg. 2003. “Fractionalization”. Journal of Economic Growth 8 (June): 155-194. 29 Marshall, Monty G., Ted R. Gurr, and Keith Jaggers. Polity IV Project.Systemicpeace.org. Center for Systemic Peace, 2013. Web. 12 Feb. 2014. 24 the Penn World Table Version 7.130 dataset, I incorporated variables for, real GDP, real GDP per-capita, and population into my dataset. Using these variables, I created two new variables. First, I took the natural logarithm of the real GDP per-capita, which allowed me to evaluate the variable as a percentage rather than an absolute value. The second variable that I created was the growth rate of GDP as a percentage of the country’s GDP in the previous year. Using the GDP growth rate in my analysis allowed me to examine how a growing, stagnant, or shrinking economy affects the risk of civil war in conjunction with natural disasters. Empirical Research Design In order to test Hypothesis 1 and its subdivisions (regarding the risk of the rapid onset of civil war in a country given the frequency and severity of natural disasters), I used four logit models (Models 1-4). In each model, the dependent variable is the dummy variable representing the occurrence or non-occurrence of a civil war in any given country-year. The first logit model incorporates all independent variables that would hypothetically affect the onset of civil war: the logged number of annual natural disasters in each country; the logged number of people affected per-capita by natural disasters in each country; the logged population; the polity score; ethnic, linguistic, and religious fractionalization; the logged real GDP per-capita; and the annual percent growth of each country’s GDP. Model 2 includes the independent variables from the first model with the addition of control variables for four of the 30 Alan Heston, Robert Summers and Bettina Aten, Penn World Table Version 7.1, Center for International Comparisons of Production, Income and Prices at the University of Pennsylvania, Nov 2012. 25 five countries31 that are affected by the most natural disasters each year: China, the Philippines, Indonesia, and India. The reason for incorporating these countries into the model was to ensure that the significance of the previous independent variables was not due to outlier countries that experience an unusually high number of natural disasters each year. The third model utilizes the same independent variables as the first model, but it includes five regional control variables; these are Europe, the Middle East, Asia & Oceania, Africa, and the Americas. Without the regional controls, there would be no way of knowing if the significance of the previous independent variables could be applied globally or if it was largely tied to specific regions. Model 4 includes the same independent variables and regional controls as Model 3. However, Model 4 adds the logged number of annual natural disasters in each country lagged by one, two, and three years. These three lagged variables are added to Model 4 in the interest of testing whether any individual year prior to the observed year significantly affects the risk of civil war onset; they also serve as controls for the logged number of natural disasters in the observed year. To test Hypothesis 2 and its subdivisions (again regarding the onset of civil war, but this time incorporating people’s memory of the number and severity of natural disasters in the past decade), I used three logit models (Models 5-7). The dummy variable representing the occurrence or non-occurrence of a civil war in any given country-year is used as the dependent variable again. 31 The United States was excluded because it had no civil wars from 1950-2008. Therefore, the model would predict the onset of civil war in the United States perfectly. 26 Models 4 & 5 are the same as Models 1 & 3, respectively, with two exceptions: the interaction variable disaster/affected and the cumulative misery threshold (CMT) variable to the logit regression. Disaster/affected is defined as follows: ln(annual # of disasters) * ln(annual # of people affected per-capita) The CMT is equal to the sum of the value of the equation above, sorted by country, for every observation where there are 10 country-years preceding it.32 Therefore, there are no CMT values for any country before the year 1960, as the dataset begins in 1950; this also means that if a country was founded after the year 1950, there can be no values for CMT until this country is at least 10 years old. By observing the significance of the CMT (a population’s memory of every natural disaster and its severity that has occurred in the past 10 years), it is possible to determine if there is a tipping point where a population has become miserable and frustrated enough with their situation that they will organize into armed groups to overthrow their government. Model 7 is designed to highlight the significance of the ‘cumulative’ aspect of the CMT. It adds variables for disaster/affected lagged by one, two, and three years. Variables for disaster/affected lagged by years 1-10 are not included because they dilute the significance of the other independent variables too greatly. 32 I determined 10 years to be the significant timespan to sum for analysis after testing 5, 10, and 15 years for significance in the model. Five years and 15 years were both insignificant in their effect on the risk of civil war onset. 27 To test my final hypothesis, Hypothesis 3 (regarding the effect of natural disaster on the intensity of a pre-existing civil war), I use one linear regression model (Model 8). The dependent variable of the regression is the number of battle deaths per 10,000 people living in the country with a civil war. Model 8 utilizes each of the key independent variables that would hypothetically affect the intensity of a civil war: the logged number of annual natural disasters in each country; the logged number of people affected per-capita by natural disasters in each country; the logged population; the polity score; ethnic, linguistic, and religious fractionalization; the logged real GDP per-capita; and the annual percent growth of each country’s GDP percapita. The Rapid Onset of Civil War (Hypothesis 1) Overall, my results suggest that as the annual number of natural disasters that occur within a country increase, the risk of a civil war occurring in that same year increases as well; this trend is consistent with Hypothesis 1. The risk of civil war is further increased in countries that are relatively large, democratic, fractionalized (ethnically and linguistically), and/or experience stagnant or negative economic growth in terms of their GDP per-capita. Further, the results suggest that the number of people affected by natural disaster per-capita does not have any significant effect on the probability of the onset of civil war. 28 Table 1: The Rapid Onset of Civil War (1950 – 2008) Civil War Occurrence Log # Natural Disasters Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Odds Ratio Odds Ratio Odds Ratio Odds Ratio 1.377*** (0.0863) 1.421*** (0.0924) 1.330*** (0.0849) 2.344 (1.756) 1.358*** (0.0507) 1.288* (0.174) 2.638*** (0.641) 3.160*** (0.615) 0.143*** (0.0270) 0.977*** (0.00751) 2.891 (2.134) 1.393*** (0.0584) 1.175 (0.168) 1.945** (0.531) 3.633*** (0.856) 0.153*** (0.0300) 0.978*** (0.00760) 0.140*** (0.106) 0.544* (0.191) 1.050 (0.339) 0.741 (0.232) 2.762 (2.104) 1.347*** (0.0522) 1.660*** (0.251) 1.587 (0.448) 4.342*** (1.059) 0.189*** (0.0367) 0.977*** (0.00741) Log # Natural Disasters (1 year lag) Log # Natural Disasters (2 year lag) Log # Natural Disasters (3 year lag) Log # People Affected Per-Capita Log Population Polity Score Ethnic Fractionalization Linguistic Fractionalization Religious Fractionalization % Annual GDP Growth Per-Capita China Philippines Indonesia India Europe Middle East Asia & Oceania Africa Americas N 0.000200*** (0.000129) 0.00103*** (0.000648) 0.000406*** (0.000267) 0.000427*** (0.000268) 0.000508*** (0.000326) 6275 6275 6275 *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.10 Standard Error in parentheses 1.179* (0.109) 1.116 (0.106) 1.091 (0.103) 0.966 (0.0887) 3.110 (2.375) 1.331*** (0.0554) 1.577*** (0.244) 1.645* (0.466) 4.109*** (1.007) 0.185*** (0.0362) 0.978*** (0.00753) 0.000258*** (0.000178) 0.00124*** (0.000834) 0.000494*** (0.000344) 0.000538*** (0.000360) 0.000632*** (0.000431) 6075 29 Hypothesis 1 theorizes that as the number of natural disasters increase within a given country-year, the risk of the rapid onset of civil war will increase as well. In Table 1, the logged number of natural disasters retains its positive significance in each of Models1-4, with varying levels of control, indicating that Hypothesis 1 may be accepted. Model 4 is the most telling, as even with the major dilution of the significance of the logged number of natural disasters by its lagged variables, the variable still retains statistical significance. In support of the argument that the immediacy of the natural disaster(s) is important when considering the risk of rapid onset civil war, none of the lagged natural disaster variables are statistically significant in Model 4. Models 1-4 also indicate that sub-hypotheses H1c and H1d may be accepted, as at the one percent significance level, increasing the size of a country’s population increases the risk of civil war and increasing the percent growth of a country’s GDP per-capita from year to year decreases the risk. Interestingly, H1a (the risk of civil war is greater in countries that are more autocratic than democratic) must be rejected. With regional controls, democracies experience the higher risk of civil war onset at the one percent significance level. However, when controlling for the countries that experienced the most natural disasters from 2000-2012, a nation’s polity score loses all significance. One possible reason for the loss of significance may be that India and the Philippines (controls) have generally had very democratic regime types from 1950 – 2008, according to their polity scores. Overall, the sub-hypothesis H1b (ethno-linguistically fractionalized countries will face a higher risk of the rapid onset of civil war) should be accepted, but only in terms of ethnicity and language. Surprisingly, as religious fractionalization increases, the risk of civil war decreases. 30 One explanation could be that countries with low linguistic fractionalization face the risk of the overwhelming majority persecuting the minority religious groups; in turn, the minority could choose the aftermath of a devastating natural disaster to seize power from the ruling majority through violence. Another explanation could be that countries with institutionalized religious freedoms, especially large countries like the United States, skew the results because states of that nature tend to be more developed and stable than states where religious freedom is not a guaranteed civil liberty. Linguistic fractionalization significantly increases the risk of civil war at the one percent level in all four models, while ethnic fractionalization generally maintains its positively correlated significance. Unexpectedly, this study indicates that the number of people affected per-capita by natural disasters in a given country-year has no significant effect on the risk of rapid onset civil war and, therefore, H1e must be rejected. One constraint of this variable is the extreme difficulty of accurately accounting for the number of people that a natural disaster effects. However, this study considers it to be the most accurate indicator of the severity of a natural disaster, as the figure is the most inclusive provided by the EM-DAT (including the number of people who are injured, require immediate assistance, and those who are left homeless). 31 Table 2: The Marginal Effect of Natural Disasters on the Rapid Onset of Civil War (1950-2008) Table 2 displays 21 observations.33 Each observation indicates a baseline number of natural disasters that occur in one country-year, beginning at 0 (observation #1) and increasing by increments of 5, with observation #21 equal to 100 natural disasters occurring in a single country-year. The first column (labeled ey/dx) indicates the increase in the probability of the rapid onset of civil war given one additional natural disaster, using the median global observation. For instance, observation #1 represents the occurrence of zero natural disasters. The corresponding value in the first column tells us that if the number of natural disasters 33 Table 2 uses the number of natural disasters as its unit of analysis, while Models 1-4 used the logged number of natural disasters. The natural log was used in the logit model because the distribution of natural disasters is extremely right-skewed (most observations have 0-5 natural disasters per year). Using the number of natural disasters in this table allows for enhanced clarity during interpretation. 32 increases from zero to one, then the risk of the rapid onset of civil war will increase by probability 0.0142, or 1.42%. Another example: at a baseline of 20 natural disasters (observation #5), an increase to 21 natural disasters raises the probability of civil war by approximately 1.38%. Expectedly, as the number of baseline natural disasters increases, the marginal effects of one additional disaster on the risk of civil war decreases. Each observation is statistically significant at the five percent significance level (column 4, labeled P>|z|). Given the fact that civil wars occur in only 801 of this study’s 7,596 country-year observations (10.55%), one natural disaster increasing the risk of rapid onset civil war by 1.42% is a telling statistic. Population Memory of Natural Disaster and the Onset of Civil War (Hypothesis 2) The key difference of Models 5-7 from the previous models is their inclusion of the cumulative misery threshold (CMT) variable. My findings indicate that the CMT is, in fact, highly statistically significant. Therefore, the theory that as the number and severity of natural disasters in the recent past increases, the risk of the onset of civil war also increases may be accepted. Essentially, a population’s memory of numerous and/or significant natural disasters will increase the likelihood that there will be a civil war in the present; this holds true with or without the variable of the logged number of natural disasters (the key variable of the Hypothesis 1 models) included in the same model. 33 Table 3: Memory of Past Natural Disasters & the Risk of Civil War (1950 – 2008) Civil War Occurrence Log # Natural Disasters Log # People Affected Per-Capita Log Population Polity Score Ethnic Fractionalization Linguistic Fractionalization Religious Fractionalization % Annual GDP Growth Per-Capita Disaster/Affected Model 5 Model 6 Model 7 Odds Ratio Odds Ratio Odds Ratio 1.243*** (0.0892) 1.289 (2.025) 1.362*** (0.0555) 1.502*** (0.218) 4.126*** (1.074) 2.490*** (0.506) 0.115*** (0.0231) 0.982** (0.00836) 0.869 (0.843) 1.206*** (0.0879) 1.953 (3.074) 1.363*** (0.0578) 1.758*** (0.285) 2.475*** (0.746) 4.107*** (1.050) 0.144*** (0.0303) 0.984* (0.00823) 0.743 (0.736) 1.365*** (0.162) 1.420*** (0.178) 0.000193*** (0.000135) 0.000747*** (0.000517) 0.000277*** (0.000201) 0.000304*** (0.000210) 0.000433*** (0.000304) 5238 Disaster/Affected (1 year lag) Disaster/Affected (2 year lag) Disaster/Affected (3 year lag) Cumulative Misery Threshold Europe Middle East Asia & Oceania Africa Americas N 5238 *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.10 Standard Error in parentheses 1.360*** (0.0602) 1.761*** (0.289) 2.486*** (0.749) 4.104*** (1.049) 0.144*** (0.0301) 0.983** (0.00823) 1.214 (0.702) 1.145 (0.108) 1.087 (0.105) 0.974 (0.0920) 1.379** (0.178) 0.000201*** (0.000147) 0.000780*** (0.000562) 0.000291*** (0.000218) 0.000319*** (0.000230) 0.000453*** (0.000329) 5238 34 The onset of civil war is once again the dependent variable of Models 5-7. Again, the logged number of natural disasters per country-year is highly significant in Models 5 and 6 (at the one percent significance level). Models 5-7 conclude essentially the same results as Models 1-4 for the independent variables testing each sub-hypothesis: democratic countries face a higher risk of civil war (H2a rejected); ethnically and/or linguistically fractionalized countries are more at risk of civil war, but religiously fractionalized countries have a reduced risk (H2b partially accepted); large countries are more at risk (H2c accepted); the higher the percent growth in GDP per-capita from one year to another, the lower the risk of civil war (H2d accepted); the number of people affected by natural disasters per-capita in a given country-year has no significant effect on the likelihood of civil war onset (H2e rejected). The enlightening figure produced by these models is the CMT. With zero control variables, the CMT is significant at the one percent level (Model 5); this is also the case when the five region controls are added to the model in Model 6. Model 7 proves that the ‘cumulative’ factor of the cumulative misery threshold is important. The model includes the disaster/affected variable for a given country-year, as well as its lagged variables for one, two, and three years prior. It is important to remember that the CMT is composed of the sum of the disaster/affected variable over the 10 years before it. Therefore, Model 7 is testing the significance of the individual components of the CMT as well as the CMT itself. According to the model, the individual years that are summed to create the CMT are not statistically significant on their own; however, the CMT still retains significance at the five percent level. The conclusion that can be drawn from these results is that as a population experiences more natural disasters and/or more 35 intense natural disasters over 10 years, in the following year the risk of the onset of civil war is significantly increased. Table 5: Marginal Effect of the Cumulative Misery Threshold on the Risk of Civil War (1950 – 2008) ey/ex mis_thresh~10 _at 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 .0765699 .151754 .2254374 .297501 .3678226 .4362769 .5027368 .5670737 .6291587 .6888634 .7460609 .8006273 .8524423 .901391 .9473645 .9902619 1.029991 Delta-method Std. Err. z P>|z| [95% Conf. Interval] .0276865 .0543475 .079856 .1040794 .126881 .1481207 .1676566 .1853467 .2010507 .2146319 .2259596 .234911 .2413738 .2452486 .2464515 .2449158 .2405953 2.77 2.79 2.82 2.86 2.90 2.95 3.00 3.06 3.13 3.21 3.30 3.41 3.53 3.68 3.84 4.04 4.28 0.006 0.005 0.005 0.004 0.004 0.003 0.003 0.002 0.002 0.001 0.001 0.001 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 .0223053 .0452349 .0689226 .0935091 .1191403 .1459657 .1741359 .2038009 .2351066 .2681925 .3031882 .3402102 .3793584 .4207124 .4643285 .5102357 .5584327 .1308344 .2582731 .3819522 .501493 .6165048 .7265882 .8313377 .9303466 1.023211 1.109534 1.188934 1.261044 1.325526 1.382069 1.430401 1.470288 1.501549 Table 5 displays 17 observations. The difference between each observation is equal to a 0.25 unit increase in the cumulative misery threshold (CMT), beginning at 0.25 (observation #1) and ending at 4.25 (observation #17). The first column (labeled ey/ex) indicates the increase in the probability of the occurrence of a civil war given an increase in the CMT of 0.25 units. Evidenced by the values of the first column, as the CMT increases incrementally, the probability of civil war increases drastically, first by 7.66%, then essentially doubling to 15.18%, and so on with gradually decreasing marginal effects for each 0.25 unit increase. While the CMT increases, each observation becomes increasingly more significant (observe the fourth column, labeled P>|z|). 36 Graph 3: Average, Across All Countries, of the Number of Natural Disasters and Civil War Graph 3 shows that, until around the year 2000, the growth in the global frequency of natural disasters was fairly steady. After 2000, one may observe the decline in their frequency that continues today. From 1990 to 2000, there is a decrease in the number of civil wars around the world. At roughly the same time (1990), natural disasters begin to increase. Civil wars break their decline in the year 2000, or 10 years after the global spike in the number of natural disasters; the timing of this increase in civil wars is consistent with the theory of the cumulative misery threshold, a population’s memory of natural disasters and their intensity over the past 10 years. 37 Intensity of Civil War (Hypothesis 3) Table 5: Natural Disaster and the Intensity of Pre-Existing Civil War (1950 – 2008) Model 8 Battle Deaths per 10,000 People Coefficient 0.684 (0.196) 0.0489 Log # People Affected Per-Capita (0.162) 0.722* Log Population (0.134) 0.0501*** Polity Score (0.0308) 0.626 Ethnic Fractionalization (0.661) 0.456 Linguistic Fractionalization (0.374) 1.839 Religious Fractionalization (1.738) 0.896*** % Annual GDP Growth Per-Capita (0.0282) N 657 *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.10 Standard Error in parentheses Log # Natural Disasters Hypothesis 3 theorizes that the intensity of a pre-existing civil war will be increased when a natural disaster or natural disasters affect the host country in a given country-year. However, according to Model 8, the data does not support this hypothesis. The logged number of natural disasters per year, which was so highly significant in past models when discussing the onset of a civil war, has absolutely no significant effect on the number of battle deaths that occur during a civil war. A possible explanation for the lack of significance could be that when calculating battle deaths resulting from war, there is a major amount of error. One study argues 38 that the PRIO battle death estimates are too low by a factor of three.34 My study utilized battle deaths as the dependent variable of the intensity model due to the lack of available data that documents the start and end dates of civil wars, past and present; this constraint, the inability to test intensity based upon the duration of civil wars, is worthy of note when discussing the inability to accepted Hypothesis 3. Implications & Conclusions Given the acceptance of Hypotheses 1 & 2, that natural disasters increase the risk of the rapid onset of civil war and that a population’s memory of natural disasters and their severity over the past 10 years increases the risk of civil war in the current year, it is essential that governments around the world take precautions to reduce their risk of war. It is important to remember that the natural disasters included in this study needed to satisfy at least one of four requirements: 1) more than 10 killed, 2) more than 100 affected (injured, require assistance, left homeless), 3) state of emergency declared, and/or 4) call for international assistance. To reduce the risk of rapid onset disasters, governments should seek to eliminate the possibility of any of these categories being fulfilled by building infrastructure to withstand natural disasters or reducing risk by building settlements away from areas with high natural disaster frequency. While the number of people affected by natural disasters per-capita was not a significant variable on its own, it is important to remember that it was incorporated into the highly significant, summed interaction variable cumulative misery threshold, indicating that a government should 34 Spagat, Michael, Andrew Mack, Tara Cooper, and Joakim Kreutz. "Estimating War Deaths: An Arena of Contestation." Journal of Conflict Resolution 53.6 (2009): 934-50. Sage Journals. Web. 29 Mar. 2014. 39 attempt everything within its power to protect its citizens from the negative effects of natural disaster if it hopes to avoid the onset of civil war. The importance of preventative planning is even more essential if a country is large, democratic, ethnically or linguistically fractionalized, and/or faces stagnant or negative GDP percapita growth, as indicated by the models employed in this study. However, the unfortunate truth is that countries that fall into this category more often than not lack the resources to adequately prepare for natural disasters and will continue to face a higher risk of civil war as a result. It can become a vicious cycle, especially as the severity of natural disasters continues to increase globally. Ultimately, there is little that can be done to decrease the number of natural disasters that occur each year and their severity, at least in the short-term. It seems that the best solution for a government to decrease their risk of civil war through the occurrence of natural disasters is to continue to develop economically and to create stable, inclusive regimes where ethnic and linguistic groups are not excluded nor discontented. 40 Bibliography – Literature Bergholt, Drago, and Päivi Lujala. "Climate-Related Natural Disasters, Economic Growth, and Armed Civil Conflict." Journal of Peace Research 49.1 (2012): 147-62. No Records. Web. 17 Feb. 2014. Brancati, Dawn. "Political Aftershocks: The Impact of Earthquakes on Intrastate Conflict." Journal of Conflict Resolution 51.5 (2007): 715- 43.Http://brancati.wustl.edu/. 2007. Web. 22 Nov. 2013. "Country and Lending Groups." Worldbank.org. The World Bank, n.d. Web. 23 Mar. 2014. <http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-classifications/country-and-lending-groups>. "EM-DAT Glossary." Emdat.be. Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters, 2009. Web. 1 Apr. 2014. Fearon, James D. "Iraq's Civil War." Foreign Affairs 86.2 (2007): 2-15. JSTOR. Web. 4 Feb. 2014. Gugoff, Casey. "Climate Change and Conflict in Migration from Bangladesh to Assam (India)." American.edu. American University, Dec. 2011. Web. 25 Mar. 2014. Guha-Sapir, Debarati, Philippe Hoyois, and Regina Below. .Reliefweb.int. Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters, Aug. 2013. Web. 20 Mar. 2014. Maxwell, John W., and Rafael Reuveny. "Resource Scarcity and Conflict in Developing Countries." Journal of Peace Research 37.3 (2000): 301-22. JSTOR. Web. 10 Dec. 2013. Nel, Philip. and Marjolein Righarts. "Natural Disasters and the Risk of Violent Civil Conflict." International Studies Quarterly 52 (2008): 159-85. www2.comm.niu.edu. 2008. Web. 22 Nov. 2013. 41 Slettebak, Rune T. "Don't Blame the Weather! Climate-Related Natural Disasters and Civil Conflict." Jpr.sagepub.com. SAGE Journals, 31 Jan. 2012. Web. 23 Nov. 2013. Spagat, Michael, Andrew Mack, Tara Cooper, and Joakim Kreutz. "Estimating War Deaths: An Arena of Contestation." Journal of Conflict Resolution 53.6 (2009): 934-50. Sage Journals. Web. 29 Mar. 2014. "Terminology." United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. United Nations, 30 Aug. 2007. Web. 4 Feb. 2014. "The Great Bhola Cyclone." Geol105naturalhazards.voices.wooster.edu. The College of Wooster, 23 Oct. 2012. Web. 25 Mar. 2014. United States of America. United States Agency for International Development. The Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance. A Critical Juncture Analysis, 1964-2003. By Richard S. Olson. Miami: Florida International University, 2005. Bibliography – Data Alan Heston, Robert Summers and Bettina Aten, Penn World Table Version 7.1, Center for International Comparisons of Production, Income and Prices at the University of Pennsylvania, Nov 2012. Alesina, Alberto, Arnaud Devleeschauwer, William Easterly, Sergio Kurlat, and Romain Wacziarg. 2003. “Fractionalization”. Journal of Economic Growth 8 (June): 155-194. EM-DAT: The OFDA/CRED International Disaster Database – www.emdat.be - Université catholique de Louvain – Brussels – Belgium. Lacina, Bethany & Nils Petter Gleditsch, 2005. ‘Monitoring Trends in Global Combat: A New Dataset of Battle Deaths’, European Journal of Population 21(2–3): 145–166. 42 Marshall, Monty G., Ted R. Gurr, and Keith Jaggers. Polity IV Project. Systemicpeace.org. Center for Systemic Peace, 2013. Web. 12 Feb. 2014.