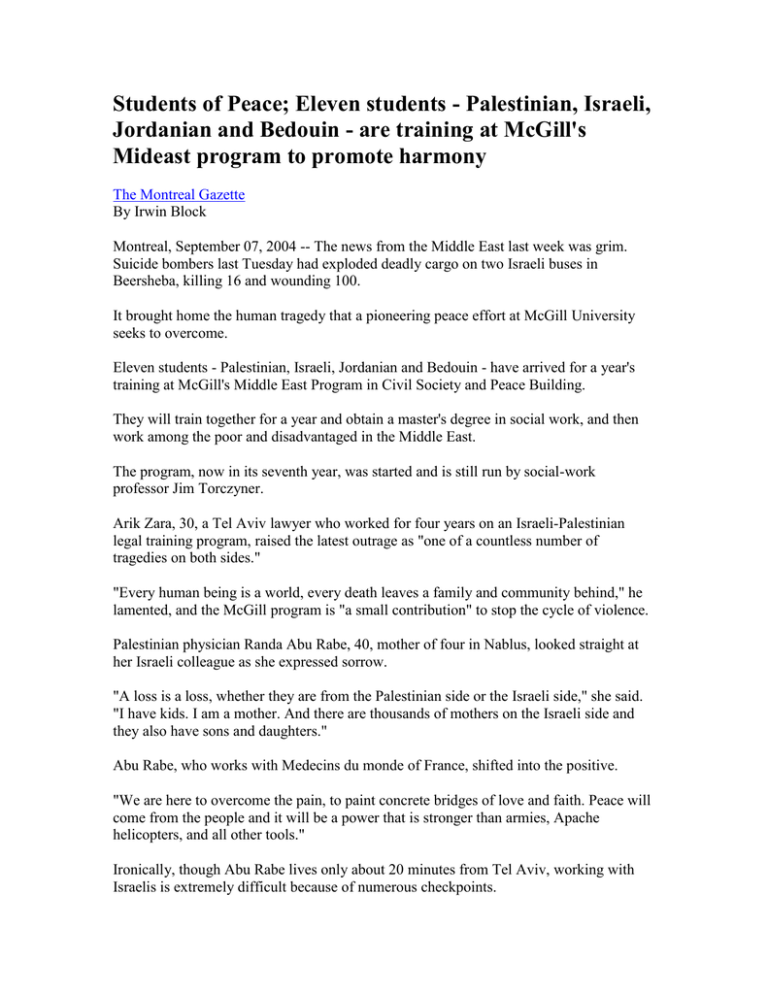

Students of Peace; Eleven students - Palestinian, Israeli,

advertisement

Students of Peace; Eleven students - Palestinian, Israeli, Jordanian and Bedouin - are training at McGill's Mideast program to promote harmony The Montreal Gazette By Irwin Block Montreal, September 07, 2004 -- The news from the Middle East last week was grim. Suicide bombers last Tuesday had exploded deadly cargo on two Israeli buses in Beersheba, killing 16 and wounding 100. It brought home the human tragedy that a pioneering peace effort at McGill University seeks to overcome. Eleven students - Palestinian, Israeli, Jordanian and Bedouin - have arrived for a year's training at McGill's Middle East Program in Civil Society and Peace Building. They will train together for a year and obtain a master's degree in social work, and then work among the poor and disadvantaged in the Middle East. The program, now in its seventh year, was started and is still run by social-work professor Jim Torczyner. Arik Zara, 30, a Tel Aviv lawyer who worked for four years on an Israeli-Palestinian legal training program, raised the latest outrage as "one of a countless number of tragedies on both sides." "Every human being is a world, every death leaves a family and community behind," he lamented, and the McGill program is "a small contribution" to stop the cycle of violence. Palestinian physician Randa Abu Rabe, 40, mother of four in Nablus, looked straight at her Israeli colleague as she expressed sorrow. "A loss is a loss, whether they are from the Palestinian side or the Israeli side," she said. "I have kids. I am a mother. And there are thousands of mothers on the Israeli side and they also have sons and daughters." Abu Rabe, who works with Medecins du monde of France, shifted into the positive. "We are here to overcome the pain, to paint concrete bridges of love and faith. Peace will come from the people and it will be a power that is stronger than armies, Apache helicopters, and all other tools." Ironically, though Abu Rabe lives only about 20 minutes from Tel Aviv, working with Israelis is extremely difficult because of numerous checkpoints. Getting to know people from the other side is one of the most attractive parts of the program, she noted. "Everybody knows that Arik is my friend and I really like the way he thinks and how he evaluated the situation. We are not politicians, we are people working to spread the peace among the people and on the ground, not just on paper." The program was boosted in December by $4.4 million in funding over three years from the Canadian International Development Agency. The program runs five centres modelled after Montreal's Project Genesis, the Cote des Neiges drop-in centre that counsels and advocates for the poor and elderly. Similar centres serve Arabs and Jews in Jerusalem, Beersheba, Nablus and Amman. Amman's Sweileh Centre has changed people's lives, said Mohammed Al-Hadid, president of the Jordan Red Crescent and a member of the McGill program's executive and management committees. The centre battles illiteracy, counsels women on issues like inheritance and divorce and even reunited a mother with a son abducted by her father, Al-Hadid said. By bringing academics and social activists together, this program builds links that can only nurture the push for peace, he noted. "We can't look the other way like our parents did at one time." Jordanian Samar Ata Alshahwan, 35, who has two law degrees and practises as a social worker, stresses that social progress in the area is impeded by violence and instability. In her research in tourist-dependent southern Jordan, she found that the second intifada led to a significant drop in tourism, which created more poverty. "You cannot separate peace, politics and human rights from people's livelihood and daily life." Some Palestinians do not support her working with Israelis, but Abu Rabe was adamant that people on both sides have to move forward. "We have to find pride in the future and go toward it. This is one of the reasons I came here, to make peace among the people, to persuade the politicians that peace is a necessity." © The Gazette (Montreal) 2004