“P ” M ’

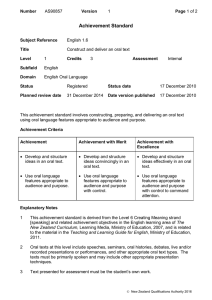

advertisement

New Zealand Applied Business Journal Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 “PERFORMANCE IS THE ONLY THING THAT MATTERS” A COMPARISON STUDY OF FRONT-LINE STAFF’S ATTITUDES TOWARD CUSTOMER SERVICE AND ACTUAL SERVICE DELIVERY IN THE HOSPITALITY INDUSTRY Herb de Vries School of Business Christchurch College of Education Christchurch, New Zealand herb.devries@cce.ac.nz Kelly de Lambert School of Business Christchurch College of Education Christchurch, New Zealand kelly.delambert@cce.ac.nz Abstract: Tourism is a key service industry for the New Zealand economy, generating an estimated NZB$11.5 in overseas exchange annually, equating to 9.3% of GDP and 16% of export earnings. New Zealand offers the global traveller breathtaking scenery, unique heritage and culture, and an abundance of outdoor activities. That said however, an important component of the New Zealand experience is delivered not through cultural experiences and landscapes but through the hospitality industry. Excellence in frontline customer service in hotels is a key component of competitive advantage, reinforcing the need for staff training programmes directed at achieving higher standards of customer satisfaction. Literature suggests that developing the ‘right’ attitude in staff is an important component of creating excellent customer service. This paper reports the findings of a study into the relationship between the quality of customer service within an organisation and the attitudes of that organisation’s staff towards factors relating to customer service as described by a specified marketing concept. The analysis is intended to engender discussion as to the relevance of such research with respect to the delivery of training programmes for frontline hotel staff. Key Words: Tourism, Customer service, Hospitality. TOURISM’S CONTRIBUTION TO THE NEW ZEALAND ECONOMY Over the past two decades, tourism has steadily transformed New Zealand’s regional and national economies. The transformation is evident in all sectors of these economiesfrom the traditional tourist-related ones like food and beverage, accommodation, visitor attractions, transport, souvenirs and conference facilities through to those not so commonly associated with tourism, such as agriculture and financial services. Statistics New Zealand (2000) estimates international and domestic tourism expenditure to be $NZB11.5, or 9.3% of gross domestic product (GDP). Information from Statistics New Zealand’s Provisional Tourism Satellite Account 1998–2000 report (2001a), which measures 1 Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 New Zealand Applied Business Journal tourism’s contribution to the New Zealand economy, including GDP, export earnings, total tourism expenditure, GST, employment, and so on, confirms that tourism is one of New Zealand’s largest export earners. The report also suggests that tourism is responsible for generating 16% of our export-related earnings, a figure greater than that for any other single export category in New Zealand. Moreover, the indirect tourism value added to supplier industries for the year ending March 2000 was $NZM4,739 (Statistics New Zealand, 2001b). The tourism industry is also significant in terms of our employment statistics. For the year ending March 2000, for example, the industry employed 94,000 full-time equivalent persons (Statistics New Zealand, 2001b). According to Ministry of Tourism (2000) figures, tourism accounts for one in every 10 jobs in New Zealand. Other tourist-related information compiled by Statistics New Zealand (2001b) reveals the changing profile of tourism in New Zealand. For example total international visitor numbers to this country grew by 85% during the previous decade. For the year ending August 2001, international visitors numbered 1.97 million, an increase of 11.3 % over the previous year’s figure. Although domestic tourist numbers are difficult to measure, Ministry of Tourism figures for 2000 show that domestic tourism grew by 40% during the 1990’s. The accommodation survey, conducted by Statistics New Zealand (2002), indicates that domestic visitors spent at least 1.3 million nights in short-term commercial accommodation in April 2002. Domestic overnight trips for 1999, for example, were estimated to number 17.2 million. Although domestic tourism accounts for 90% of all visitor numbers, it contributes only 44% of all visitor expenditure (excluding day trip expenditure) (Ministry of Tourism, 2000). The money spent by both international and domestic tourists is a major impetus for regional development throughout New Zealand, with every region benefiting. The report published by Tourism New Zealand late in 2000 estimated that international visitor spending would be $NZB4.7 for that year, with the government receiving GST revenue of $NZM478 ( Tourism and education services are the only New Zealand export industries liable for GST). While figures such as these provide solid evidence of the importance of tourism to New Zealand’s national and regional economies, other, often lesser known, indices can also be used to measure the industry’s contribution. One of these is “total guest nights”, an index that indicates how long tourists stay in particular areas, and in what numbers. Travellers who stay longer and in larger numbers presumably spend more, thereby enlarging the economic 2 New Zealand Applied Business Journal Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 contribution that tourism makes to the broader New Zealand economy. It follows that New Zealand’s reputation and performance in the hospitality industry has a direct impact on tourism success. A key to competitive advantage (and consequently organisational effectiveness) in this industry is the delivery of excellence in customer service, which Schoell and Guiltinan (1995) define as the totality of what an organisation does to add customerperceived value to its basic products. In the hospitality industry, we can assume that frontline staff and the attitudes they hold about customer service play a key role in this regard. It was on the basis of this premise that we conducted a study to determine whether the attitudes of frontline staff are linked to the quality of customer service delivery in a sector of New Zealand’s hospitality industry. Before reporting that study, we provide some further information concerning the contribution that accommodation makes to tourism in New Zealand and offer brief discussion on the notions of customer service and staff attitudes, particularly in terms of methodological considerations associated with determining the latter. We also document the development of the hypotheses tested in this study. THE ACCOMMODATION INDUSTRY’S CONTRIBUTION TO THE SUCCESS OF TOURISM Accommodation options for travellers within New Zealand are wide and varied in terms of the type of accommodation provided, the services available and the standard of service provided. Not surprisingly, the substantial increase in tourist numbers over recent years has seen a commensurate increase in demand for accommodation. Demand for top-of-the-range accommodation, providing first-class service and a wide range of facilities, in particular, has increased with the rising number of international visitors. The latest Statistics New Zealand accommodation survey (2002) reports that guests spent 2.3 million nights in short-term commercial accommodation in April 2002, 1% more than in April 2001. Total guest nights for the year ended April 2002 were up 7% on the year ended April 2001, and up 13% on the year ended April 2000. Figure 1 also shows the generally steady increase in total guest nights over recent years, especially during December and January (two of the peak months for both national and international tourism in New Zealand). 3 Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 New Zealand Applied Business Journal Source: Statistics New Zealand (2002), Accommodation survey, Wellington, Author. Figure 1 Total guest nights (ooo) for the years 1999–2002. THE IMPORTANCE OF CUSTOMER SATISFACTION As Brooks (1995) observes, customer satisfaction is critical to every business’s long-term success. The concept describes a customer’s positive response to a service or product; their “delight” as Kotler, Armstrong, Meggs, Bradbury & Grech. (1999) put it. Brooks furthermore contends that in this world of over-supply, customer service has become the great differentiator among competing companies. Customer satisfaction, he says, is not just important to one’s business; it is the business. Customers are saying, “Your performance is the only thing that matters to us. Words are simply words, promises are empty and excuses are irritating. Your performance is our only reality” (p. 5). The hospitality industry is no exception in this regard, and, in fact, is probably more reliant on customer satisfaction than many other businesses. Yet, despite the strategic shift to a service culture within this industry over recent years, many hotel executives and employees do not have a commitment to customer service (Bullivant, 2001; Healy, 1993). Healey, in making this point in 1993, stressed the need to develop a “customer-first” attitude in frontline hospitality industry staff. In a similar vein, Bullivant (2001) points to the need for the right training in order to instil the right attitudes and a professional approach to the job in hand. MEASURING ATTITUDES AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF HYPOTHESES So what attitudes on the part of frontline staff are relevant to effective customer service and how can these be measured? Liska (1975) contends that attitude has attracted more attention from behavioural scientists than has any other behavioural characteristic. He goes on to say 4 New Zealand Applied Business Journal Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 that the measurement of attitude has generally proceeded as a kind of quasi-psychophysical problem. That is, it is assumed that attitudes are latent hypothetical variables that cannot be measured directly but can only be inferred from observations of a subject’s responses to a selected set of graded behavioural opportunities. Dawes (1972), however, in arguing that attitudes are more easily measured than defined, has described attitudes as a “state of mind of the individual toward a value” (p.15). It is this notion of value that we consider particularly relevant to this study. In an attempt to make understanding of this notion more explicit, we turn to a model that McCarthy, Perreault and Quester (1995) developed to demonstrate how an organisation’s “marketing concept” is fundamental to its organisational success. Customer satisfaction Total company effort The Marketing Concept Profit (or alternative measure of longterm success) as an objective Figure 2 Marketing concept model. Source: McCarthy, E.J., Perreault, W.D. & Questor, P.G. (1997), Basic marketing: A managerial approach (2nd ed.), Roseville, NSW: McGraw-Hill, p. 24. In constructing this model, McCarthy et al. (1995) held to a philosophy of management wherein a business: exists to satisfy targeted customers’ wants involves a company-wide marketing effort (an integrated or systems approach) seeks to earn a satisfactory return on investment or achieve some other performance objective. In essence, the model suggests that an organisation which makes its marketing concept integral to all facets of its business increases the likelihood of organisational success by focusing the company’s full and combined effects on customer satisfaction and achievement 5 Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 New Zealand Applied Business Journal of organisational performance objectives. One limitation of McCarthy et al.’s model that became apparent within the context of our study is that the model applies to the organisation as a whole, whereas our aim was to measure the collective excellence in customer service delivered by individuals within organisations. However, if we return to Brooks’ (1995) earlier assertion that excellence in customer service (which in this study focuses on the collective individual efforts of frontline staff within the hotel industry) leads to greater organisational success, we can develop the following formula: If Marketing Concept = organisational success and Excellence in customer service = organisational success then Marketing Concept = excellence in customer service This equation easily lends itself to the adaptation of McCarthy et al.’s marketing concept model outlined in Figure 3, and in so doing allows us to see that frontline staff must possess the following if they are to be effective in delivering excellent customer service; an attitudinal desire to satisfy customer needs an acceptance that their role within the organisation is relevant and important to organisational success an understanding that their attitudes to personal achievement reflect their achievements in their job. 6 New Zealand Applied Business Journal Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 Effort at an organisational level through the understanding of their role, its importance and relevance Belief in the need to satisfy customers Marketing Concept Excellence in Customer service applied by individual staff Personal achievements reflected in organisational achievements Figure 3 Adaptation of McCarthy et al (1997) marketing concept model. An implicit assumption in this model is that staff will be more effective in delivering excellent customer service when their attitudinal behaviour is in line with the marketing concept variables of: the creation of customer satisfaction organisational effort and relevance personal and organisational goal attainment. This premise led, in turn, to developing the following hypotheses that informed our study. Hypothesis 1: Frontline staff in the hospitality industry are more effective in delivering excellent customer service when their attitudes reflect a greater acceptance that their own personal achievement goals need to be in line with organisational goals. Hypothesis 2: Frontline staff in the hospitality industry are more effective in delivering excellent customer service when their attitudes reflect a greater acceptance that each staff member has an important and relevant part to play within the organisation. Hypothesis 3: Frontline staff in the hospitality industry are more effective in delivering excellent in customer service when their attitudes reflect a greater acceptance that there is a need to create customer satisfaction. 7 Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 New Zealand Applied Business Journal We should also note at this point that we were concerned, when designing our study, as to whether the types of attitudinal values described here could be measured quantitatively in order to allow us to conduct tests of significance in relation to our hypotheses. Eiser and van der Pligt (1993) suggest that while converting people’s qualitative responses to a numerical score is a challenge, especially because of its potential to reduce something that may be rich and complex to a single index that then assumes an importance out of all proportion to its meaning, it does have the advantage of allowing comparisons of attitudes held by different peoples (or groups of people), or of the attitudes of a single person in different contexts or at different times. This attribute was an important one for our study. Furthermore, polls, surveys and other instruments designed by the likes of Likert, Thurstone and Guttman continue to be widely used and widely accepted means of capturing attitudinal information in numerical form (for discussions on the validity of these tools, see Lincoln & Kalleberg, 1990; Liska, 1975; Oppenheim, 1966; Schuman & Presser, 1981). THE STUDY The study was conducted within a major New Zealand hotel chain. The following qualitative and quantitative information was gathered to test the three hypotheses: 1. Management perceptions of customer service in two hotels, each from a different New Zealand region, followed by observation of the customer service in those hotels. 2. The attitudes toward customer service held by frontline staff in three hotels, each from a different New Zealand region. Two of these regions were the same as those in (1). We had ascertained before conducting this research that the Region one hotel and the Region two hotel were distinctly different in their customer service quality. The first was identified as less than satisfactory and the other as excellent (criteria for these determinations are listed below). The aim was to determine whether there was any significant difference between the attitudes held by staff from the two hotels in relation to the marketing concept variables. We collected information from a Region three hotel for simple comparative purposes. Participants Each of the three study groups comprised a variety of hotel staff, ranging from room attendants, restaurant and bar staff, porters, receptionists and supervisors. 8 New Zealand Applied Business Journal Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 Study Group One (Region one) comprised staff working in a hotel located in one of New Zealand’s foremost tourist destinations. This location was selected for the following reasons: The hotel chain’s Human Resource Manager had suggested that customer service in this particular hotel could be significantly improved. The hotel manager held serious concerns about customer service in the hotel. Staff in the region tend to be a transient, seasonal and of a young age. (accommodation tends to be expensive and short-term, which is not helpful to attracting long-term staff) A 24-hour observation of hotel operations, especially in relation to the restaurant, bar, rooms, cleaning and other services, highlighted some issues with respect to standards of customer service. Table 1 provides a summary of the observation findings. Overall Uniform attitude to customers Acceptable Not worn by level of all staff friendliness Partly worn by Generally some staff helpful when approached Satisfactorily maintained Restaurant service Staff-to-staff interaction Food of high Friendly but standard rather critical of one another Slow service Somewhat Inconsistent impersonal in service (e.g. their soup arriving interactions during main) Incomplete orders: not supplied as requested. Hotel appearance Reception Issues of Friendly untidiness (e.g. mess Helpful behind partitions, door at reception left open to reveal a half-eaten staff meal, and messy office floor visible to guests) Friendliness variable Table 1 Qualitative survey of level of customer service of study group one (Region 1) Study Group Two (Region 2) was selected from a major provincial urban centre. This destination was chosen for the following reasons: The hotel chain’s Human Resource Manager suggested that the particular hotel provided the benchmark in customer service for the chain. Management at the hotel were proud of the level of customer service provided and pleased with staff attitudes to delivery of customer service. The region had a stable workforce, with many of the hotel staff having strong provincial ties and a sense of pride in their district. Most were living locally in ‘affordable’ accommodation. 9 Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 New Zealand Applied Business Journal A 24-hour observation of hotel operations, especially in relation to the restaurant, bar, rooms, cleaning and other services, which confirmed the excellent customer service status of this hotel. Table 2 provides a summary of the observation findings. 10 New Zealand Applied Business Journal Overall Uniform attitude to customers Very friendly Worn by all staff Very helpful Immaculately Approach maintained guests to offer help Consistent standard of Personal touch dress noticeable Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 Restaurant service Staff-to-staff interaction Food of a Friendly, good standard helpful, supportive of Extremely one another friendly service Sense of enjoyment in Professional their and helpful interaction Flexibility delivery customer requests Hotel appearance Reception Clean and tidy Extremely friendly staff Well maintained conversational, Everything in helpful and place cheerful in of Water supplied without asking Table 2 Qualitative survey of customer service of study group two (Region 2) Study Group Three (Region 3) was selected from a main city centre. The hotel in this region was chosen for comparative purposes only and was not subject to observation or an interview with hotel management. This region has a workforce consisting of stable and transient workers, with staff tending to have weaker provincial ties than those in Region 2. Most staff lived locally in reasonably affordable accommodation. The Human Resource Manager of the hotel chain considered that this hotel delivered a generally good level of customer service. Research Instruments Staff of the three hotels were asked to respond to a questionnaire designed to measure their attitudes to the three hypotheses variables discussed above. Participants were asked to rate a series of statements on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”. The questionnaires were administered to staff before they attended a staff professional development seminar during July and August 2001. Participation was voluntary and anonymous. A total of 89 questionnaires were returned 23 of a possible 25 from Study Group 1, 44 of a possible 45 from Study Group 2 and 22 of a possible 23 from Study Group 3. 11 Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 New Zealand Applied Business Journal The questionnaire statements were written according to the three variables given in Figure 2 and the hypotheses. The assumption that only three variables would be needed to account for the variances in customer service is a decided limitation of this instrument. Another is the assumption that each statement would have equal weighting in terms of assessing staff attitudes to customer services. A third limitation has already been discussed, that of trying to capture attitudinal data numerically. A fourth limitation is that we did not subject the questionnaire to tests of reliability and construct validity. However, the questions were drawn from similar instruments and a close reading of relevant literature. A final limitation related not so much to the questionnaire itself but to the conditions under which it was administered. The fact that staff were asked to complete it just before attending the seminar may have influenced the way they answered it. Data Analysis Mean scores across all statements pertaining to each of the three variables were calculated for each of the three groups in order to ascertain trends (as denoted by the means). The overall means for each of the three attitudinal variables for Study Groups One and Two were then subjected to a test of statistical significance (t test) in order to prove or disprove each hypothesis. Significance was set at a level of p = 0.05. RESULTS Our findings failed to show distinct differences in the attitudes held by staff across the three regions regarding their contribution to achieving their organisation’s goals, their personal importance and relevance to the organisation, and the need to create customer satisfaction. In fact, the attitudes of staff across the three regions in respect to these three attitudes were very similar, as the mean scores for each questionnaire statement in Tables 3 to 5 show. 12 New Zealand Applied Business Journal Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 Group 1 Group 2 Group 3 Mean (SD) 1. I have personal interests such as sports, hobbies or 3.09 clubs that are much more important than my work.* (1.08) Mean (SD) 3.33 (1.05) Mean (SD) 3.23 (1.19) Total Survey Mean (SD) 3.24 (1.09) 2. I am a person that puts my vocation (job) as my first priority. 3.61 (1.08) 3.37 (1.16) 3.05 (1.13) 3.35 (1.14) 3. My job is only a very small part of who I am.* 2.48 (0.98) 4.26 (0.45) 2.81 (1.37) 4.02 (1.03) 2.50 (1.10) 3.91 (1.06) 2.65 (1.22) 4.06 (0.93) 5. My personal and family needs come before 2.18 anything else.* (0.73) 2.14 (1.13) 1.91 (1.11) 2.09 (1.04) 6. I get great satisfaction out of working hard at my job. 4.09 (0.60) 4.37 (0.79) 4.55 (0.60) 4.34 (0.71) 7. My job helps me to search for what I am good at 3.74 and what I can accomplish with my life. (1.01) 3.81 (1.03) 3.77 (1.02) 3.78 (1.01) 8. A job with a steady income and good benefits is far 3.45 more important than one of personal growth and (0.91) achievement.* 3.44 (0.91) 3.45 (0.86) 3.45 (0.89) 3.39 (0.46) 3.41 (0.60) 3.30 (0.61) 3.37 (0.57) 4. Through doing my job I am also achieving some of my personal goals. Goal attainmentaverage Table 3 Frontline hotel staff’s attitudes regarding goal attainment Note: Each positive statement (in line with the attitudinal variable) required a response on the Likert scale in which 1= strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree, while each contrary to the attitudinal variable (denoted by *) required a response in which 1 = strongly agree and 5 = strongly disagree. 13 Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 New Zealand Applied Business Journal Region 1 Region 2 Region 3 Mean (SD) 1. I should be expected to complete my job 3.71 description – nothing more.* (1.14) Mean (SD) 3.93 (1.24) Mean (SD) 4.27 (0.55) Total Survey Mean (SD) 3.97 (1.09) 2. I prefer to put more effort into my job than is 3.95 expected of me (0.49) 4.23 (0.52) 4.32 (0.57) 4.18 (0.54) 3. I see my job as important to the success of this 3.95 organisation. (0.74) 4.09 (0.78) 3.90 (1.04) 4.01 (0.84) 4. Working as part of the ‘company team’ is the most important aspect of my job. 3.96 (0.82) 4.09 (0.97) 4.14 (0.71) 4.07 (0.87) 5. I am not concerned with the success, growth or 3.65 expansion of this organisation.* (1.07) 4.02 (1.06) 4.36 (0.73) 4.01 (1.01) 6. I would like to see this organisation succeed and 4.48 achieve its goals. (0.51) 4.58 (0.54) 4.55 (0.96) 4.55 (0.66) 7. I am proud to work for this company. 3.95 (0.58) 3.30 (0.93) 4.18 (0.79) 3.71 (1.01) 4.18 (0.73) 4.23 (0.97) 4.13 (0.72) 3.73 (1.02) 3.86 (0.37) 4.10 (0.50) 4.26 (0.47) 4.08 (0.49) 8. It is not my job to broaden or promote the organisations ideals.* Importance/relevance to organisation average Table 4 Frontline hotel staff’s attitudes regarding their personal importance and relevance to the organisation Note: Each positive statement (in line with the attitudinal variable) required a response on the Likert scale in which 1= strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree, and each contrary to the attitudinal variable (denoted by *) required a response in which 1 = strongly agree and 5 = strongly disagree. 14 New Zealand Applied Business Journal Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 Region 1 Region 2 Region 3 Mean (SD) 1. ‘First and foremost’ my responsibility is to satisfy 4.83 customer’s needs (0.39) Mean (SD) 4.73 (0.45) Mean (SD) 4.68 (0.48) Total Survey Mean (SD) 4.74 (0.44) 2. It is the responsibility of management to deal with 3.65 customer dissatisfaction.* (0.93) 3.37 (1.35) 3.86 (0.83) 3.57 (1.14) 3. I so not see my job as primarily being of service to 3.86 others.* (0.99) 3.91 (0.98) 4.27 (1.03) 3.95 (1.05) 4. It makes me angry having to deal with customer problems when I have other work to do.* 3.83 (1.03) 4.00 (0.90) 4.50 (0.51) 4.06 (0.91) 5. It is not my responsibility to ensure that this 4.17 organisation presents an image of excellence in (0.94) customer service.* 4.17 (1.08) 4.73 (0.70) 4.31 (0.98) 6. Helping co-workers to provide excellent service, is 4.55 very important to me. (0.60) 4.72 (0.50) 4.68 (0.48) 4.67 (0.52) 7. I get satisfaction in finding new ways to improve customer service 4.17 (0.49) 4.33 (0.64) 4.41 (0.59) 4.31 (0.59) 8. I do not believe it is my job to look for improvements in customer service.* 3.96 (1.07) 4.16 (1.09) 4.55 (0.51) 4.20 (0.98) Customer service - average 4.12 (0.47) 4.17 (0.47) 4.46 (0.31) 4.22 (0.46) Table 5 Frontline hotel staff’s attitude’s regarding the creation of customer satisfaction Note: Each positive statement (in line with the attitudinal variable) required a response on the Likert scale in which 1= strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree, and each contrary to the attitudinal variable (denoted by *) required a response in which 1 = strongly agree and 5 = strongly disagree. Similarly, the t-tests for the two independent samples, Groups One and Two, did not support the three hypotheses. For Hypothesis One, the computed t-value of –0.14 had a p-value of 0.444, indicating very little evidence of a difference in the average attitudes to personal achievement estimates for the two groups. For hypothesis two, the computed t-value of –1.89 had a p-value of 0.036, indicating little evidence of a difference in the average attitudes to importance and relevance for the two groups. And for hypothesis three, the computed t-value of –0.15 had a p-value of 0.442, again indicating very little evidence of a difference for the 15 Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 New Zealand Applied Business Journal two groups in the average attitudes to customer satisfaction estimates. In short, the present study cannot claim any relationship between staff attitudes and the quality of customer service as observed in the subject hotels. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS Although differences in actual service delivery were identified across the three hotels that participated in our study these were not echoed in the attitudes that frontline staff held in relation to the marketing concept variables (as found in this study). The mean attitudinal scores relating to those variables however did point to trends that could form the basis of further investigation. First, the results for attitudes towards personal and organisational goal attainment (refer Table 3) suggest that the participants in Study Group One (the hotel rated as ‘less than satisfactory’) placed marginally greater emphasis on personal interests than did those in Study Group Two (the hotel rated as ‘excellent’). This difference may be related to the transient nature of the Study Group One workforce and the attractions afforded them by the outdoor nature of the region. Furthermore, Study Group One appeared to be more inclined than Study Group Two to see their job as only a very small part of who they were and to gain less satisfaction from their work. Second, the survey results for the attitudes towards an individuals’ personal importance and relevance to the organisation (Table 4) suggest that participants in Study Group One were more inclined than those in Study Group Two to complete only work that was expected of them and were less likely to put any more effort into their job than was expected of them. Generally, the former group seemed less inclined to be concerned with the organisation’s success or promoting its goals. The average for this section was lower, overall, for Study Group One, which suggests attitudes less supportive of the organisation. Yet the difference was far from conclusive in setting a trend. Third, the survey results for attitudes towards customer service (Table 5) suggest that all three study groups had a good understanding of the importance of customer service. The overall mean scores were higher here than the corresponding scores for the previous two sections of the survey. However, Study Group One did appear slightly more inclined than the other two to consider management as responsible for customer dissatisfactions and hence 16 New Zealand Applied Business Journal Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 were more inclined to become angry at having to deal with customer problems. They also seemed to gain slightly less satisfaction out of helping customers and to be less likely to look for ways of improving customer service. The inconclusive nature of these findings should not detract from the importance of further efforts to establish a link between the attitudes of hospitality industry staff to their work and the quality of customer service actually delivered. The findings may have been as much an outcome of methodological limitations as anything else. Refinement of the survey instrument in particular, the way in which qualitative aspects (especially in terms of its validity and reliability) of the survey were conducted and sample size may produce quite different results. In this regard any future replication of this study should ensure the rating approach used to measure hotel customer service quality is robust in terms of reliability and validity, a larger sample size and clear defining of respondent variables e.g. age, vocation, etc may also assist. What is certain is that identification of all factors that impact on the quality of customer service delivered by staff in the New Zealand hospitality industry is vital given the important contribution that accommodation makes to the quality of New Zealand’s tourism industry. In this regard, further research could be done in the area of employees’ attitudes toward their own importance and relevance to the organisations in which they work, given that this was the variable that seemed to offer the most differentiation between the scores of the groups in this present study. Other variables could also be considered. Such as the perceptions and selfesteem of frontline staff. Only by identifying those factors that are critical for ensuring sound delivery of customer service within the hospitality industry can we ensure that customer service training for frontline staff is appropriately targeted. 17 Volume 1, Number 1, 2002 New Zealand Applied Business Journal REFERENCES Brooks, I. (1995). The Yellow Brick Road. Auckland: Nahanni Publishing. Bullivant, G. (2001). Credit management. Stanford, CA: 2001. Dawes, R. M. (1972). Fundamentals of attitude measurement. New York: John Wiley & Sons. Eiser, J. R. & van der Pligt, J. (1993). Attitudes and decisions. London: Routledge. Healey, W.J. (1993). Hotel and motel management; 208,3, p5 Kotler, P., Armstrong, G., Meggs, D., Bradbury, E. & Grech, J. (1999). Marketing: An introduction. Sydney: Prentice Hall. Lincoln, J. R. & Kalleberg, A. L. (1990). Culture, control and commitment: A study of work organisation and attitudes in the USA and Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Liska, A. E. (1975). The consistency controversy: Readings on the impact of attitude on behaviour. New York: Halsted. McCarthy, E. J., Perreault, W. D. & Quester, P.G. (1997). Basic marketing: A managerial approach. (2nd ed.). Roseville, NSW: McGraw-Hill Ministry of Tourism. (2000). New Zealand tourism strategy 2010. Wellington: Author. Oppenheim, A. N. (1966). Questionnaire design and attitude measurement. New York: Basic Books. Schoell, W.F. & Guiltinan, J.P. (1995). Marketing (6th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Schuman, H. & Presser, S. (1981). Questions and answers in attitude survey: Experiments on questions and answers in attitude surveys. New York: Academic Press. Statistics New Zealand. (2000). Key statistics. Wellington: Author. Statistics New Zealand. (2001a). Provisional tourism satellite account. Wellington: Author. Statistics New Zealand. (2001b). International visitor arrivals. Wellington: Author. Statistics New Zealand. (2002). Accommodation survey. Wellington: Author. 18