BELIEFS AND EXPECTATIONS OF PRINCIPLES OF MARKETING STUDENTS

advertisement

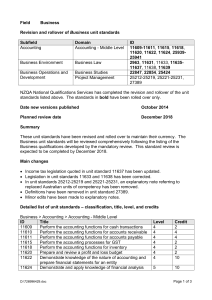

BELIEFS AND EXPECTATIONS OF PRINCIPLES OF MARKETING STUDENTS Tom Johnson, EIT Abstract Research conducted in the United States over recent years about Marketing Principles has revealed that the majority of students believe that the subject is best defined as selling, advertising and promotion. Significantly, students thought that marketing was unethical and many questioned marketing as a career choice. Whilst such research indicates student views at the beginning of a course, little, if anything, is suggested about how or when attitudes and opinions towards marketing principles change. A survey of thirty-three New Zealand marketing students was undertaken after fourteen weeks of lectures to assess possible changes in attitudes to marketing. Results would tend to indicate that students’ attitudes and opinions alter, though the time and reason for change remain unknown. It is thought that method of instruction and actual delivery by lecturing staff does contribute to this change, but this requires further investigation. Introduction Principles of Marketing courses have been taught at higher educational institutions around the world for nearly a century Tomkovick (2004). In an age of sophisticated telecommunication, computer software packages, and Internet technologies, marketing lecturers have resources of which early educational pioneers could only have dreamed. The delivery of material has changed, but early marketing teachers faced the same challenges faced today; how to engage students in a meaningful, learning environment. This research was stimulated by Ferrell and Gonzales (2004) who surveyed three hundred and nineteen students prior to commencing a Marketing Principles course, to determine their beliefs and expectations. The students were asked eight open-ended questions to assess their knowledge and awareness of marketing. Results indicated that they believed marketing comprised of selling, advertising, and promotion. Almost half believed marketing was a bad business practice, and nearly one-quarter thought that it was a poor career choice. Over a four-year period, students enrolled in Marketing Principles at the Eastern Institute of Technology have expressed similar views about advertising and promotion. This project was conducted fourteen weeks into a Marketing Principles course to assess what possible changes in perception and attitudes towards marketing would have occurred. Where changes have occurred, existing research has identified specific intervention methods, which had the most impact. The current research also has focused on the attitudes and teaching methods of lecturers that students deemed most effective in bringing about changes in their perception. Method The research was conducted using both secondary and primary methods. Proquest and library facilities were used to collate and analyse academic literature and information about the teaching of Marketing Principles. A questionnaire was designed and pre-tested before being used on respondents. Students were advised that the information collected in the survey was anonymous and that it would be used to compare perceptions about marketing principles and teaching methods of the United States of America. Thirty-three students took part in the survey. The questionnaire was divided into three parts. The first section consisted of three open-ended questions aimed at identifying how students would define marketing to a friend, and positive and negative thoughts students had about marketing. These questions enabled a comparison to be drawn with the American research. The second section listed seven learning methods and asked students to rate these according to how important they were to their learning. A 4-point Likert Scale was used that categorised each learning method from “Very important” to “Not important”. The final section used a Semantic Differential technique, which listed ten key teaching factors in the delivery of Marketing Principles. The ten teaching factors were adapted from Tomkovick (2004), and embraced similar attributes of outstanding teaching covered by Faranda and Clarke (2004), Conant, Smart and Kelley (1989), and Smart, Kelley and Conant (2003). The research complied with ethical standards set by Eastern Institute of Technology’s Ethics Committee from whom approval was obtained prior to the survey being conducted. The study is limited by its focus on a single institution, the comparatively small sample in a region of New Zealand compared to earlier USA studies and the interpretation of terminology used overseas. Objectives The overall objective of the current study was to compare the beliefs and attitudes of marketing principles students in New Zealand to those of the United States. Specific objectives included ascertaining what learning methods New Zealand students deemed most important, and assessing New Zealand student’s impressions on what aspects of lecturer delivery were important to their learning. D:\99035746.doc 2 Literature Review Marketing Principles Many aspects of a Principles of Marketing course have been investigated (Ferrell & Gonzales, 2004), but there has been only limited information available to describe how students feel about marketing before their first course. Ferrell and Gonzales (2004) found that students believed marketing essentially consisted of promotion and advertising. Many students believed that marketing was simply a course you had to take to get a business degree. Dailey and Kim (2001, p.59) attempted to measure market-orientation principles that students acquire in their first course and how their market orientation can be improved. They concluded that the principles course produced a, "relatively low absolute increase in overall student market orientation” (disconcerting to many lecturers), yet stated "successful completion of the principles of marketing course should result in a significant increase in overall student marketing orientation." There is little data to support Dobscha and Foxman’s (1998) contention that because of deficiencies in the 4 Ps model, the Principles of Marketing course should focus on the exchange framework as a superior mode for teaching the subject. For the purpose of this research, the 4Ps model has been retained as the contextual basis for the teaching and learning of marketing principles. Teaching Environment Student’s beliefs or perceptions of what marketing is, before they begin a marketing principles course is probably not that important, if the learning and teaching environment is exemplary. Excellence in teaching, as advocated by Conant, Smart and Kelley (1988), is the key. There are many academic dissertations on how to improve the learning environment and teaching methods from Burns (1994) who suggested a stand-alone computer simulation designed to enhance the learning of basic marketing concepts. Alternatively, Drea, Singh, and Engelland (1997) examined the use of a marketing audit within the Principles of Marketing course as an experiential learning technique, whilst Celuch and Slama (2000) measured perceptions of a marketing course taught with a critical thinking approach. Teaching Intervention Methods Peterson, Albaum, Munuera and Cunningham (2002) found that in spite of the use of instructional technologies at an accelerated pace, there was little evidence of an incremental contribution of these technologies to student learning. Siguaw and Simpson (2003), in a satirical look at marketing classes, concluded that students are more interested in having fun and the personal characteristics of the “professor” than in the subject matter. Hurdle (2004) also found a positive relationship between expectations for a course being interesting and fun and the material learned being more valuable. D:\99035746.doc 3 A good deal of research on improving teaching delivery exists. Jaju and Kwak (2000) found that marketing students prefer concrete experience and active experimentation in their learning, while Johnson, Johnson and Golden (1996) found that both involvement and realism were significant predictors of perceptions of learning. Smith and Van Doren (2004) advocated reality-based learning as a simple method for keeping teaching relevant and effective. Acker (2003), in researching outstanding college teachers and the difference they make, concluded that teacher attributes include: having and showing enthusiasm for teaching; emphasising active, participatory learning and critical thinking skills; setting and enforcing high academic standards; genuinely caring about students; and, possessing both a command of ones subject and essential teaching skills. Faranda and Clarke (2004), whose research was on student observations of outstanding teaching, found there were five predominant themes for outstanding teachers – rapport, delivery, fairness, knowledge and credibility. These same themes are evident in Tomkovick’s (2004) Ten Anchor points for more effective teaching of marketing principles. Ethics It is concerning that a high proportion of American students surveyed felt that marketing was a bad business practice and a poor career choice. Ultimately they live in a consumer society and marketing affects all of them in some way in almost everything they do. Pressure in American education has come from the American Assembly of Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) and the American Marketing Association requiring colleges of business to incorporate ethics education into undergraduate programs (American Marketing Association, 2004). Whilst most textbooks used in New Zealand marketing principles classes have sections devoted to ethics and social responsibility in every chapter, many ethical issues emerge in marketing, and it is very important these are addressed. Attributes – Honesty, Caring, Humour and Atmosphere Teaching intervention methods are often restricted by time constraints and are limited to those that prove most effective within such constraints. Just as honesty breeds trust, teaching and learning demand active engagement and mutual respect (Yoo and Donthu, 2002; Hagstrom, 1997). Kleine (2002) expands on the importance of enhancing student’s roles and Gremler and McCullough (2002) examined student satisfaction guarantees, as a means of delivering what was promised. Dishonesty undermines the process of education. Caring lecturers are important to students and humour can lead to a classroom atmosphere conducive of effective learning. Loomax and Moosavi (1998) point out that humour is an extremely effective tool in education. “Classrooms in which laughter is welcome help bring learning to life,” according to Chiasson, (2002, p.1). Tomkovick (2004, p113) states, “Humour and positive thinking provide the salve for the wounds…and where on earth is humour and joy more appropriate (and needed) than in a Principles of Marketing classroom.” Chiasson, (2002, p.2), adds that, “The job of a teacher is to get students laughing, and when their mouths are open give them something to chew on.” D:\99035746.doc 4 Seemingly, honesty, caring and humour combine to assist the creation of an important classroom requirement. Commanday (1993) believes that teachers’ reputations or images created outside the classroom play a part in establishing a classroom atmosphere. Faranda and Clarke (2004) found that motivation from professors/lecturers came in many forms, such as enthusiasm for teaching, well prepared classes, approachability and the development of human relationships. Studies link enthusiasm and overall attitudes to positive learning outcomes (Ferrell & Gonzales, 2004). According to Stein (2001), teachers must create a classroom atmosphere of mutual respect and trust, select instructional tasks that prompt students to take different positions and find different solutions to learn effectively. Other Elements The literature reflects on a number of other elements that are important contributors to student learning. Passion is identified by many authors (Tomkovick, 2004; McCoombs & Whistler, 1997; Day, 2004; Elliott & Crosswell, 2001) as providing a strong connection to good teaching and subsequent learning. Ferrell and Gonzales (2004) note that the professors who best motivated students also had the greatest success in facilitating learning. Another element of effective teaching is preparedness. This phenomenon of effective teaching according to Tomkovick (2004) is having something to say, keeping abreast of change and being able to engage students with multiple activities that motivate students to learn. Juric, Todd and Henry (1997) provide a hint to a further element concerning high standards when they indicate that many students enrolled in Principles of Marketing because they thought it was easy. According to Celsi and Wolfmbarger (2002) classroom innovation contributes to the setting of high standards. Tomkovick (2004) supports Juric et al (1997), notion but goes on to indicate that high standards in areas of content, presentation and assessment are integral part of teacher effectiveness. Lastly in this area is the element of humility. Humility is important to students and is poignantly phrased by Tomkovick (2004, p.114), “Confess when you are wrong, praise those with a knowledge greater than yours on a topic, and laugh at yourself when you do make a mistake.” Understanding students' perceptions in this challenging environment is critical to successfully teaching students and enables the perception of an accurate and clear understanding of the marketing discipline. D:\99035746.doc 5 Discussion Definition Whilst 60% of American students surveyed prior to attending marketing principles classes defined it as involving selling and/or advertising, the situation was different with New Zealand students not unexpectedly, as they had had fourteen weeks of tuition. However, whilst 91% of the class were either correct or partially correct in their definition of marketing less than half (42%) gave a fully correct definition. This is a quite disturbing factor that in spite of 14 weeks learning nearly half the class (48%) still only defined marketing in a partially correct manner. A further (9%) of the class gave an incorrect definition. Why? Is this a reflection on poor instructional methods, poor delivery or the ability of a student? In this instance, students, instructional methods and delivery form an important triangle in the learning process. The purpose of the first question in the New Zealand survey was initially intended to enable a comparison to be drawn directly with the American survey about what marketing meant when described to a friend. A direct comparison can’t be made because the New Zealand students had the advantage of fourteen weeks classes on the subject. The fact that 60% of American students defined marketing as basically advertising and promotion, before attending classes, is probably consistent with the views of many people in both countries and not really important. What is more disturbing in the New Zealand results after fourteen weeks of teaching is that less than half the class were able to define marketing accurately. To find out whether this was a student learning deficiency, teaching failings or some other reason would require further research. TABLE 1: New Zealand Student Definitions of Marketing. Definition of marketing Correct Partially Correct Incorrect Total n 14 16 3 33 % 42 49 9 100 Positives Students were asked to explain the positives about marketing they had acquired in their studies. The results were interesting. Over 50% believed the main positive was acquiring a better understanding of marketing. A further 21% found that the subject was interesting and fun and a further 18% expressed that they felt they had a better understanding of buyer behaviour. This may be due to an emphasis placed by the lecturer on the importance of understanding buyer behaviour as a precursor to being a knowledgeable marketer. Whatever the reason, it is interesting to find that slightly less than three-quarters of the class (73%) could be linked with a common thread of better understanding of the subject being the most important positive gained from the course. The findings in this section enabled a direct comparison to be made with American results. D:\99035746.doc 6 The most positive thoughts about marketing held by the American students surveyed were; that marketing concepts were interesting or fun (50%); and, that marketing was important for business practice (29%). A further (3%) thought the subject would be easy. There is an interesting correlation between the Americans’ rating the subject interesting and fun, and New Zealand students rating this the second most positive factor acquired. High levels of interest and fun are important elements in class atmosphere and teaching delivery, covered extensively in research by Tomkovitch and others. It may seem paradoxical that a significant number of students, who claimed to have acquired a better understanding of marketing and/or buyer behaviour as a positive, were unable to give a correct definition of marketing. Positive perceptions should be used to build a bridge to reach students and engage them in learning course content. TABLE 2: Positive thoughts about marketing Positive thoughts about Marketing Better understanding of marketing Interesting and Fun Better understanding of buyer behaviour Other Total n 18 7 6 2 33 % 55 21 18 6 100 Negatives Students were then asked to explain their negative thoughts about marketing. Over one-third of students (35%) found that Marketing Principles was too broad a subject and too full in scope. A further 25% pointed out that marketing was ethically dishonest and manipulative in its advertising strategies. At the time of the survey, students had completed two assignments requiring some quite substantial research. As a consequence 15% of students found research work time consuming and dull. A further 9% felt that the jargon and terminology used in marketing was difficult to understand. Part of this problem emanates from the use of textbooks that can complicate concepts and facts about marketing. Thus there is an onus on the lecturer to make the subject matter more understandable and enjoyable for students. This possible approach is similar to the view of Faranda and Clarke (2004) who noted that delivery, knowledge and credibility and preparedness contribute to a good learning experience. It is interesting to note that of the negatives expressed in the research of Faranda and Clarke (2004), only one item appears to match the current study; that is, that students perceived the marketing principles course to be difficult (22%). However, other results from the same research seem markedly different. For example, they found that 46% of students perceived marketing to be a poor business practice and that a further 24% felt it was a poor career choice. The saga of Enron and other major corporate collapses, pricing scams, insider trading, false advertising and corporate fraud make these perceptions understandable and probably account for the 43% of the students who felt that businesses most of all need to be honest. This theme of honesty has an important parallel in the New Zealand research. Here, 25% of students felt that, marketing was unethical, dishonest at D:\99035746.doc 7 times and manipulative in its strategies and advertising. The findings supports Faranda and Clarke (2004) contention that Professors (lecturers) need to guard against focusing only on concepts and frameworks that do not address how marketing affects society and further that to overcome the belief that marketing is bad business practice. Adequate coverage of marketing ethics and an understanding how marketing fits into society should be incorporated in the class. Ethics should be presented as an issue that affects every aspect of business, not just marketing. TABLE 3: Negatives about Marketing Negative thoughts about Marketing Too broad and difficult a topic. Scope too large Unethical, dishonest and manipulative marketing strategies and advertising Research time consuming/ dull Jargon and terminology cause difficulties None Other Total n 11 8 % 35 25 5 3 3 2 33 15 9 9 7 100 Learning Methods Marketing Principles is presented to students over a sixteen-week course with a set number of topics. Because students attend two classes of two hours duration each week, the structure of the lessons and the number of different delivery and learning methods is limited. The list of seven learning methods in the survey was derived from the literature and an assessment made of the most common practices in New Zealand. Of the seven methods, five are classroombased and two are student task-based activities. In an age of constructivism, it may surprise that the most important method rated by the students was Lectures (3.85). This was followed by assignments (3.48) and Power Point presentations (3.48) as next in importance. These three are followed in sequential order of priority by textbooks (3.27), case studies (3.06) and videos (3.00). Group work was rated least important (2.79). The importance of classroom/lecture driven activities to students was further confirmed in the final section of the survey where students listed their most important lecturer attributes. If the class atmosphere is good then these methods are appropriate. The poor assessment of group work probably comes from an assessment by students that not all students do their fair-share in-group work and also because of the conflicts that often arise. D:\99035746.doc 8 TABLE 4: Student ratings of instruction methods in order of importance Instruction Method Lectures Assignments Power Point Textbook Case studies Videos Group work Mean 3.85 3.48 3.48 3.27 3.06 3.00 2.79 Delivery Methods Students were provided with ten paired adjectives concerning components of lecturer delivery in class. They were asked to rate these items across a sevenpoint scale. Five of these items were presented with a positive at the left end of the scale and five with a negative as the starting point. Positive and negative start points were therefore randomised across the ten items. In applying the scale and assessing the results, lower average scores are seen to reflect higher levels of importance in any delivery item; the lower the score the better the assessed item. Students’ perceptions of the best form of delivery by lecturers produced some interesting results. Honesty (1.36) was regarded by the New Zealand students as the most important factor in an effective instructor. There is a linkage here with the same students (25%) believing that, “marketing was unethical, dishonest at times and manipulative in its strategies and advertising,” and the American results that marketing was a bad business practice. Dishonesty undermines the process of education, and students want honesty in content and delivery. Caring rated next at (1.48). Stated perhaps best by Tomkovitch (2004) in citing Senator Jack Kemp. Another important factor in effective teaching is humour, rated (1.52) by students. “Classrooms in which laughter is welcome help bring learning to life.” (Chiasson, 2002, p.) A positive classroom atmosphere rated (1.55), confirming the studies of (Dana et al. 2001; Eckrich 1990; Friedman 1991; Haley 1992; and Lentos, 1997) linking enthusiasm and class atmosphere to positive learning outcomes. Passionate delivery (1.70) rated next. This also confirms the views of Day (2004) and Fried (1995) who argued that a sense of passion is essential to all good teaching. Preparedness (1.73), good use of time (1.97) and high standards (2.00) were next in the ratings. These are understandable requirements, closely linked not only in the delivery of teaching but, also to the more mundane duties of marking and administration of all student work and activities. Humility, an unknown word in the Australian lexicon, rated (2.32) as far as New Zealand students were concerned. Realism at 4.12 was the outlier. This was surprising as it flies in the face of the findings of Johnson et al. (1996) and Smith and Van Doren (2004) who advocated reality-based learning to keep teaching relevant and effective. D:\99035746.doc 9 This result may be due to students trying to balance the two factors of realism and theoretical in importance. TABLE 5: Semantic differential rating on delivery methods Item Honesty Caring Humour Atmosphere Passionate delivery Preparedness Good use of time High standards Humility Reality/Theoretical 1.36 ** 1.48 ** 1.52 ** 1.55 * (**) 1.70 * 1.73 1.97 2.00 2.32 4.12 * Significant by Gender ** Significant by Major None significant by age A great deal of the literature makes little, if any, attempt to demonstrate the possible relationship amongst delivery mechanisms. As a result, readers might be left with the idea that the ten items are a rather flat uni-dimensional phenomenon. To assess the relationship between the items measured in the study, a correlation analysis was applied. This revealed some very interesting results. For example, the three strongest correlation pairs were Humour – Atmosphere (.781), Honesty – Atmosphere (.669) and Humour – Caring (.660) At the other end, the lowest three pairs were Delivery with Passion - Delivery as Realistic(.051), Good use of time – High Standards (.233) and Honesty Humility (.239). Taken a further step, a similarity matrix was developed and this is shown as Table 6. What this shows is that Humour and Atmosphere (1.00) are the two most similar delivery methods, followed at a slightly lesser level by Humour – Caring (.928) and Caring and Atmosphere (.915). Full details are shown below. TABLE 6: Similarities Matrix Caring Realistic Prepared Atmosph. Humour High Stan. Passion Humility Use of Time Honesty Caring Realistic 0.284 Prepared 0.802 Atmosph. 0.915 Humour 0.925 0 0.120 0.106 0.772 0.868 1 High Stan. 0.646 Passion 0.595 Humility 0.751 Use of Ti. 0.610 0.239 0.344 0.765 0.740 0.683 0.785 0.577 0.737 0.790 0.446 0.064 0.858 0.783 0.586 0.696 0.626 0.672 0.873 0.575 0.751 0.678 0.660 Honesty 0.228 0.724 0.895 0.881 0.760 0.845 0.517 0.772 D:\99035746.doc 0.591 10 Based on the similarities in Table 6, there is potential to consider a hierarchal interconnection amongst the delivery methods and thus propose the development of a “building-block” model of delivery methods. Whilst such a model needs further investigation, a suggested structure is shown as Figure 1 in Appendix .1 Conclusions Fourteen weeks tuition by New Zealand students precluded any direct comparison being made on a definition of marketing with American students. As most people tend to regard marketing as consisting mainly of advertising and promotion, the American results are understandable. The fact that less than half the New Zealanders were able accurately to define marketing may be a student learning deficiency, a teacher failing or some other reason, which would require further research. Where negative or incorrect perceptions about marketing exist, knowledge about these issues should be incorporated into the course content and lecturer delivery. Effective teaching will help change and overcome negative views that marketing is unethical and a poor career choice. In both the American and New Zealand research, the concerns expressed over marketing ethics were very real. By experiencing the realities of marketing. students can establish their beliefs and expectations correctly, thus understanding from the course, that unethical conduct is never acceptable in marketing practice or in the classroom. Academic integrity provides the foundation upon which a flourishing academic life rests. Teaching methods need to be varied and stimulating enabling students to experience the various activities and elements of marketing through a variety of exercises, cases, and speakers or videos that relate marketing to the students' past experiences. For many students the jargon and terminology can prove difficult to learn. Part of this problem is because the textbooks used tend to be “too academic” and can complicate a simple subject. In spite of new technology and the advocacy of many different approaches to learning the traditional use of lectures, assignments, and the use of textbooks still rate highly with students as the best forms of teaching interventions. Marketing students respond positively to teachers who are honest, caring, at times humorous in their presentations, and passionate in delivering well prepared lesson content. Teachers need to set high standards, make good use of time, blend reality with theory and at all times show humility. New Zealand students in rating honesty the most important lecturer attribute, highlight the need for integrity in teaching and an ethical approach to all aspects of marketing. D:\99035746.doc 11 REFERENCES Acker, J. R. (2003). Outstanding college teachers and the difference they make. Criminal Justice Review, 28(2), 215-231. American Assembly of Collegiate Schools of Business. (1998). Enrolment trends in management education. AACSB Newsline. American Marketing Association. (2004). AMA mission stummem. Retrieved February 15, 2004, from http://www.marketingpower.com Burns, A. (1994). Micro marketing education review of applying marketing principles. Marketing Education Review. 12(1), 62-63. Celsi, R. L., & Wolfmbarger, M. (2002). Discontinuous classroom innovation: Waves of change for marketing education. Journal of Marketing Education, 24(1), 64-72. Celuch, K., & Slama, M. (2000). Student perceptions of a marketing course taught with the critical thinking approach. Marketing Education Review, 10(1), 57-64. Centre for Academic Integrity. (2006). www.academicintegrity.org/cai_research.asp. Chiasson, P. (2002). Using humour in the second language classroom. http://iteslj.org/Techniques/Chiasson-Humour.html. Commanday, P. M. (1993). Practical peace making for educators. The Education Digest, 59(3), 17. Conant, J., Smart, D., & Kelley, T. (1988). Master teaching: Pursuing excellence in marketing education. Journal of Marketing Education, 10(Fall), 3-13. Clayson, D. E., & Haley, D. A. (1990). Student evaluations in marketing: What is actually being measured? Journal of Marketing Education, 12(3), 9-17. Dana, S. W., & Dodd, F. (2000). Student perception of teaching effectiveness: A preliminary study of the effects of professors' transformational and contingent reward leadership behaviours. Journal of the Academy of Business Education, 2(Fall), 53-70. Day, C. (2004). A passion for teaching. London: RoutledgeFalmer. Drea, J. T., Singh, M., & Englelland, B. T. (1997). Using experiential learning in a principles of marketing course: An empirical analysis of student marketing audits. Marketing Education Review, 7(12), 53-59. Eckrich, D. W. (1990). If 'excellent teaching' is the goal, student evaluations are backfiring. Marketing Education (Fall), 1, 6. Elliott, B., & Crosswell, L. (2001). Commitment to teaching: Australian perspectives on the interplays of the professional and the personal in teachers’ lives. Paper presented at the International Symposium on Teacher Commitment at the European Conference on Educational Research, Lille, France. Faranda, W. T., & Clarke, I., III. (2004). What makes a good professor? A qualitative investigation of upper-level students' perceptions. Proceedings of the American Marketing Association, 15(Winter), 304. Ferrell, L., & Gonzales, G. (2004). Beliefs and expectations of principles of marketing students. Journal of Marketing Education, 26(2), 116. Floyd, C. J., & Gordon, M. E. (1998). What skills are most important? A comparison of employer, student, and staff perceptions. Journal of Marketing Education, 20(2), 103-109. Fried, R. L. (1995). The passionate teacher: A practical guide. Boston: Beacon Press. Friedmann, H. C. (1991, January). Fifty-six laws of good teaching: A sampling. Teaching Professor, 3. Gremler, D. G., & McCullough, M. A. (2002). Student satisfaction guarantees: An empirical examination of attitudes, antecedents, and consequences. Journal of Marketing Education, 24(2), 150-160. Hagstrom, R. G. (1997). The Warren Buffett way: Investment strategies of the world's greatest investor. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley. Haley, S. (1992, February). Advice for establishing an effective teaching attitude. Teaching Professor, 1-2. D:\99035746.doc 12 Hativa, N., Barak, R., & Simhi, E. (2001). Exemplary university teachers: Knowledge and beliefs regarding effective teaching dimensions and strategies. The Journal of Higher Education, 72(6), 699-729. Hurdle, P. M. (2004). Exploring marketing students' classroom expectations. Proceedings of the American Marketing Association, 15(Winter), 4-10. Jaju, A., & Kwak, H. (2000). Learning preferences of marketing students. In J. P. Workman, Jr & W. D. Perreault, Jr (Eds.), Proceedings of AMA Winter Educators' Conference (pp. 243-250). San Antonio, TX: American Marketing Association. Johnson, S. C., Johnson, D. M., & Golden, P. A. (1996). Enhanced perceived learning within the simulated marketing environment. Marketing Education Review, 6, 19. Juric, B., Todd, S., & Henry, J. (1997). From the student perspective: Why enrol in an introductory marketing course? Journal of Marketing Education, 19(1), 65-76. Kennedy, E. J., Leigh, L., & Plumlee, E. E. (2002). Blissful ignorance: The problem of unrecognised incompetence and academic performance. Journal of Marketing Education, 24(3), 243-252. Kleine, S. S. (2002). Enhancing students' role identity as marketing majors. Journal of Marketing Education, 24(1), 15-23. Lantos, G. P. (1988). Tricks of the trade: Strategies and tactics for achieving excellence in undergraduate marketing education. In Gary Frazier et al. (Eds.), 1988 AMA summer educators' proceedings (pp. 137). Chicago: American Marketing Association. Loomax, R. G., & Moosavi, S. A. (1998). Using humour to teach statistics: Must they be Orthogonal? Paper presented at the Annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Diego, April 17th, 1998. McCombs, B. L., & Whistler, J. (1997). The learner-centred classroom and school: Strategies for increasing student motivation and achievement. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Motivating students: The attitude of the professor. (1997). Marketing Education Review, 1(2), 27-38. Peterson, R. A., Albaum, G. A., Munuera, J. L., & Cunningham, W. H. (2002). Reflections on the use of instructional technologies in marketing education. Marketing Education Review, 12(3), 7-17. Siguaw, J. A., & Simpson, P. M. (2003). A marketing plan for marketing instruction: A satirical look at student comments. In H. Spotts (Ed.), Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science (pp. 129-133). Coral Gables, FL: Academy of Marketing Science. Smart, D. T., Kelley, C. A., & Conant, J. S. (2003). Marketing education in the year 2000: Changes observed and challenges anticipated. Journal of Marketing Education, 21(3), 206-216. Smith, L. W., & Van Doren, D. C. (2004). The reality-based learning method: A simple method for keeping teaching activities relevant and effective. Journal of Marketing Education, 26(1), 66-74. Stein, M. K. (2001). Mathematical argumentation: Putting umph into classroom discussions Mathematics Teaching in the Middle School, 7(2), 110. Tomkovick, C. (2004). Anchor points for teaching Principles of Marketing. Journal of Marketing Education, 26(2), 109. Wolburg, J. M., & Pokrywczynski, J. P. (2001). A psychographic analysis of generation Y college students. Journal of Advertising Research, 41(5), 33-52. Yoo, B., & Donthu, N. (2002). The effects of marketing education and individual cultural values on marketing ethics of students. Journal of Marketing Education, 24(2), 92-103. D:\99035746.doc 13 Bibliography Albers-Miller, N. D., Straughan, R. D., & Prenshaw, P. J. (2001). Exploring innovative teaching among marketing educators: Perceptions of innovative activities and existing reward and support programs. Journal of Marketing Education, 23(3), 249-259. Alderson, W. T. (1957). Marketing behaviour and executive action. Homewood, IL: Irwin. Bacon, D. R. (2003). Assessing learning outcomes: A comparison of multiple-choice and short-answer questions in a marketing context. Journal of Marketing Education, 25(1), 31-36. Bacon, D. R., & Novotny, J. (2002). Exploring achievement striving as a moderator of the grading leniency effect. Journal of Marketing Education, 24(1), 4-14. Bartels, R. (1962). The development of marketing thought. Homewood, IL: Irwin. Buchanan, R. W. (1996). The enemy within. Sydney, Australia: McGraw-Hill. Civikly, J. M. (1986). Humor and the enjoyment of college teaching. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 26, 61-69. Clayson, D. E., & Haley, D. A. (1990). Student evaluations in marketing: What is actually being measured? Journal of Marketing Education, 12(3), 9-17. Davis, R., Shekhar, M., & Van Auken, S. (2000). Relating pedagogical preference of marketing seniors and alumni to attitude towards the major. Journal of Marketing Education, 22(2), 147-154. Desai, S., Damewood, E., & Jones, R. (2001). Be a good teacher and be seen as a good teacher. Journal of Marketing Education, 23(2), 136-144. Hunt, S. D. (1976). Marketing theory: Conceptual foundations of research in marketing. Columbus, OH: Grid. Dailey, R. M., & Kim, S. S. (2001). To what extent are principles of marketing students market oriented? The review category: Marketing education. Marketing Education Review, 11, 57-72. Dobscha, S., & Foxman, E. R. (1998). Rethinking the principles of marketing course: Focus on exchange. Marketing Education Review, 8(1), 47-57. Duffus, L. (2002). SMA innovative teacher comment: Developing a personal strategic plan in the introduction of marketing course. In B. T. Venable (Ed.), Proceedings of the Society for Marketing Advances. Greenville, NC: Society for Marketing Advances. Lantos, G. P., & Shibli, M. A. (1993). Learner principles should be practised by excellent marketing instructors. Marketing Education Review, 3, 17-25. Pride, W., & Ferrell, O. C. (2005). Marketing basic concepts and decisions. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Simpson, P., & Siguaw, P. M. (2000). Student evaluations of teaching: An exploratory study of the faculty response. Journal of Marketing Education, 22(3), 199-213. Smart, D. T., Kelley, C. A., & Conant, J. S. (1999). Marketing education in the year 2000: Changes observed and challenges anticipated. Journal of Marketing Education, 21(3), 206-216. D:\99035746.doc 14