GRAPPLING WITH GROUP-WORK AND PERSEVERING WITH PEER ASSESSMENT AT UCOL

advertisement

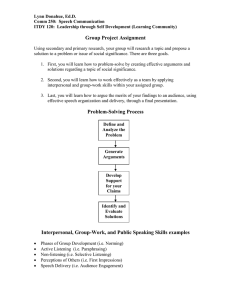

GRAPPLING WITH GROUP-WORK AND PERSEVERING WITH PEER ASSESSMENT AT UCOL Alison Rudzki, Faculty of Humanities and Business, UCOL (Universal College of Learning) Introduction Using a case study approach, this paper illustrates how group-work and self/peer assessment have been successfully integrated into the delivery and assessment of a level six paper within the Bachelor of Applied Business Studies (B.ABS) at UCOL (Universal College of Learning) in Palmerston North. The degree programme was launched in January 2005 comprising two majors in marketing and management and the paper referred to here has so far been delivered to two separate student cohorts. Background to the Case Study The paper which forms the basis of this case study is level 6 Marketing Communications, a compulsory paper for those enrolled in the marketing major of the B.ABS degree. Marketing Communications refers to the way in which organization’s attempt to communicate with various target audiences and comprises a whole range of activities from advertising and sales promotion to personal selling, public relations and direct marketing. In keeping with the applied philosophy of the B.ABS programme, the aim of the Marketing Communications paper is to develop students with the knowledge and practical experience to work effectively as marketing communications practitioners upon graduation Teaching and Learning Strategy Whilst the paper aims and learning outcomes for the paper were prescribed prior to its first delivery, the lecturer’s own experience as both a marketing practitioner and academic significantly influenced the context for teaching and learning. Furthermore, collaboration with others in the marketing industry before the start of the 2005 academic year, reiterated what was important for marketing graduates in terms of knowledge and practical skills. The teaching and learning strategy which was subsequently developed was intended to (in no particular order): • • • • • Engage students in deep versus surface learning Give students real experience of real marketing communications projects Demonstrate the value of reflective practice Simulate the workplace by engaging students in group-work Develop a range of transferable skills relevant to marketing communications practice D:\219547184.doc 1 To achieve these aims a ‘blended delivery’ approach was adopted which would provide a theoretical base, reinforced by experts in the field through external speakers, audio visual materials and case studies as well as traditional lectures and online discussions. As students moved through the curriculum, it was envisaged that they would become increasingly independent as learners and gain hands-on experience of solving problems and undertaking tasks which would serve them well in the ‘real world’, such as writing press releases and creating radio and press advertisements. Deep versus Surface Learning A key to developing deep rather than surface learning lay in the actual ‘doing’ of tasks, rather than simply hearing about ‘how to do’ through traditional lectures. Through the completion of ‘practical exercises, learning was reinforced, thus engaging students in a much deeper level of learning. Research indicates that ‘learning depends on feedback to the learner, and that providing quick and helpful feedback to students is extremely beneficial’ (Falchikov 1995, p.159), so by providing regular feedback to individuals and groups during class and following assessments, it was envisaged that students would be able to judge their progress and understand where and how they might improve. Simulating the workplace and gaining real experience The ‘hands on’ aspect was an important feature of simulating the workplace and providing students with real experience of actual marketing communications projects. Ideally, this would best be achieved by placing students in a real working environment unfortunately, whilst the B.ABS programme is based on a co-operative model, the degree does not offer a period of industrial placement. However, by bringing students and local organisations together on real projects, it was felt that students would be provided with significant opportunities to apply their learning. As a result, contacts were made with local organisation with a view to them providing some real marketing communications projects. The value of self-reflection The value of self-reflection was also considered an important principle with which to engage students, in addition to providing feedback in the form of oneon-one meetings between each student and the lecturer following the in-course test, and from members of the B.ABS teaching team and the rest of the class following student presentations of coursework. By way of encouraging students to become reflective practitioners, students would be required to reflect upon their own performance. Self assessment is of course, a learning process in itself, ‘improving student learning by passing on skills of evaluation and critical judgement’. In this sense the term 'self evaluation' used by Burgess (1999) may be more appropriate since it is about developing students' ability to self evaluate. D:\219547184.doc 2 Self-evaluation involves students taking responsibility for monitoring and assessing their own learning, thus taking the first steps towards independent and autonomous learning, and becoming reflective practitioners, therefore a key aim would be to provide students with a level of autonomy, whilst maintaining academic rigour. The merits of reflective practice have of course, been acknowledged by industry and academia over the years. The work of Donald Schon (1983) for example, led tertiary educators to seriously consider the importance of engaging students in reflecting on their actions as part of their education. Schon’s Reflective Practitioner Model proposed that knowledge was acquired in the midst of the action itself (rather than at the end, a view which had been purported by the likes of John Dewey (Kernaghan, n.d.). It is within this context then, that students would be required to get into the habit of evaluating their understanding and performance as a matter of course through regular summary and feedback sessions in class, as well as through formal self-evaluation as part of their assessment and which is discussed later. Engaging students in group-work For many academics, effective group-work, particularly that which is assessed, is notoriously impeded by problems such as differing levels of commitment to the group and resentment on the part of those who feel they are undertaking most of the work, but have little power to do anything about this; through to failure to participate and a complete break-down of the group. Given this experience, it is not surprising that many people reach the conclusion that group based work, and particularly assessment is just not worth all the stress and effort and, many students would agree. However, within the marketing industry, it is essential that people are able to work well in teams, particularly in the area of marketing communications. Therefore, no matter what the problems were, it was felt necessary that group work was crucial to the applied nature of this paper. Moreover, research suggests that students learn best when they are actively involved in the process, and regardless of the subject matter, those working in small groups tend to learn more of what is taught and retain information longer (for example Collier, 1980 and Gross-Davis, 1993). Group work was therefore weaved into classroom teaching and learning throughout the semester and it was decided that group assessment would provide a very real (if sometimes stressful) reflection of the workplace. By adding the further dimension of peer evaluation through assessment (see below), it was intended that students would also be able to develop the ability to critically evaluate other’s work in parallel with their own – as would often be the case in industry, where marketers are continually judged by their peers. D:\219547184.doc 3 Development of Transferable Skills A further aim of the teaching and learning strategy was to encourage students to develop key transferable skills. The lecturer’s personal experience, networking with marketing practitioners and regular scanning of marketing communications vacancies, as well as the work of various authors and agencies into the area of graduate employment, led to the formation of a list of skills that were particularly important to the marketer. In summary, the key skills identified included: • • • • • • • • • Adaptability and transferable skills Communication and presentation skills General team-working skills Use of Information Technology Organisation and Planning Problem Solving and Decision Making Research Skills Stress management skills Time management skills Whilst some skills development occurred within the classroom, students were forced to consider these quite specifically as part of the assessment process (discussed below). By identifying and understanding the importance of these skills, it was envisaged that this would focus the students’ attention upon planning for their future professional development and employability. Assessment Strategy Given all that needed to be assessed then, it was crucial for the assessment strategy to be inextricably linked with teaching and learning. As Race recommends, an appropriate assessment of learning outcomes was considered early in the course design: ‘‘Don’t bolt assessment on – tie it into course design.” (Race, 1995, p.65). A combination of summative and formative assessment was considered the best approach, allowing for the assessment of some initial concepts through an in-course test and to some extent a final exam, as well as ‘deeper learning’ through coursework. The assessment which resulted from this process include an in-course test to assess the understanding of basic principles. As previously mentioned, significant feedback is provided in an attempt to bring ‘up to speed’ those students who clearly have problems in understanding. The assessed project work that follows the test, requires students to form groups and undertake a major marketing communications project which is split into two distinctive parts. In the first of these, students are required to take on the role of a team of marketing management consultants for a local organisation and must work with the firm’s management to research and develop a marketing communications plan. The outcome is the presentation of a Creative Brief – a document that would provide an outline of the creative tasks an D:\219547184.doc 4 advertising, design or media planning agency would use to develop their solutions. Sponsoring organisations and the B.ABS teaching team are invited to this presentation and verbal feedback encouraged from all members of the audience in addition to lecturer’s formal assessment. The second part of the project challenges students through role reversal, to assume the responsibility of an advertising, design or media planning team and respond to the creative brief produced in the previous assessment. They are required to produce a media schedule that integrates a number of marketing communications tools e.g. radio advertisement, poster, sales promotion, including a timeline and budge – in short – they have to undertake the actual task they have set themselves in the previous assignment. This approach forces students to critically evaluate the success of their earlier work. For example, if their initial objectives were unclear, or their recommendations unrealistic or inappropriate – then they have to deal with the real consequences of this, which can be a tough lesson. Grappling with assessed group-work Given some of the problems associated with group-work which have been mentioned previously, it was imperative that assessed group-work would benefit students, rather than have a detrimental effect. Gross-Davis (2003) recommends that for success in group-work, it is essential to create tasks which require interdependence i.e. ‘the group perceives that they “sink or swim” together, that each member is responsible to and dependent on all the others, and that one cannot succeed unless all in the group succeed.’ (Gross-Davis, 2003). In short ‘knowing that peers are relying on you is a powerful motivator for group-work’ (Kohn, 1986). Furthermore, Johnson, Johnson and Smith (1993), recommend that group-work should be relevant and integral to the paper, rather than ‘just busywork’. With a significant amount of marks riding on the success of group-work, it was felt necessary to provide a safety-net for those students who might experience problems. In an attempt to alleviate some of the issues, a group self-management system was introduced which places responsibility for the effective working of the group with the students themselves, and allows students to formally penalise those who are not fully contributing to the group. The self-management system originated from the game of football and allows sanctions to be used against members who are not contributing to group work. Those individuals issued with a yellow card lose 25% of their final mark, although the sanction can be revoked if their performance improves. Should the individual continue to fail to contribute, then a red card is issued, resulting in zero marks being awarded. A red card cannot be revoked once it is issued. The difference is that the lecturer does not act as referee, instead the students themselves decide if and when it is necessary to issue a card. D:\219547184.doc 5 This approach has been used in various guises by the lecturer for over twelve years, and has proven to be very successful in both reducing the amount of group-conflict and the time spent by academics in working through problems with student groups. Self and Peer Assessment Students were given the opportunity to show the various ways in which they themselves and others in the group contribute to the effectiveness of the team through anonymous peer assessment for both pieces of project work. This involved students allocating up to 10% of the marks for each assessment themselves, by submitting a form which ranks each team member against a list of skills and application of subject knowledge. Students are encouraged to be honest in their self/peer assessment, and although the process can be anonymous, this is discouraged. Instead, emphasis is placed on the value of giving and receiving feedback and to date, all of the students have opted to allocate marks as a ‘group’ rather than individually. Has this approach worked? So, has this approached worked? From an achievement perspective, the approach does appear to have been successful. From the two students cohorts that have been through this paper, two of the 15 have failed the paper, based on their final exam results, the remainder have achieved relatively high marks overall, and particularly in the project work. Student evaluations and informal feedback at the end of each semester have provided a mixed response. General comments from students about the course include: • “I can’t believe how much I have learned. I did half of this paper at another • (name provided) university before I moved down here, but it was all theory and when I got a part-time job in marketing I was really struggling. Since starting here I’ve done lots of different things and my boss is really pleased because now I can help more. She even let me do all the marketing for one of her events and she was really rapt with the posters and the press releases I did” “I am learning a lot from BABS paper and think it will really benefit me in the area of employment. I thought working with a real business was very hard, but they give me lot of help and now offer me some work which will be very good for me I think.” Comments relating to group-work and the group management system include: • I hate working in groups, its not fair because you always get stuck with people who don’t work hard. But I thought the cards were awesome. We nearly gave a yellow one to one of the dudes but he sorted his stuff out when he found out and did some cool stuff in the end. D:\219547184.doc 6 • I’ve always tried to get out of groupwork, but it was actually ok this time cos • we could do something about it. We had power. Its cool to be treated as a adult for once. We didn’t use the system, we didn’t need it, I think the fact it was there really helped. I wish wed have had it when we did (another paper) because we had a real egg in the group and we couldn’t do anything about him and we ended up with a crap mark which wasn’t fair. With respect to self and peer assessment: • I thought this was good. We usually just talk about the subject and I don’t’ • normally think about things like how well organised I am. But I know it’s important and I know I’m really good at some things but now I have to concentrate on time management because it’s important when looking for a good job. My time management was all over the place in the project, so it was a good lesson. I think some of the other groups cheated and gave each other really good marks, but we couldnot see the point. I mean, the marks were there for a reason, you’re just a loser if you cannt see that. Comments from some of the organisations who have supported students with projects have also been supportive and two firms have already provided projects for 2007: • “What a refreshing change to get a group of students in who actually know • • what they are doing. Students are usually pretty good and writing plans, but this lot could actually implement them! They’ve saved me a lot of time and money and I have a whole list of project for your students next year”. The team came up with some fantastic ideas. The costings and plan were extremely helpful as I had initially dismissed radio, but now realise it’s an affordable option. I basically took their brochure and went straight to print – saved me a lot of hassle! Conclusion It would appear then that the approach adopted has worked well in achieving the aims of the paper and much more. Having a formal system in place to manage group-work has been extremely beneficial to both the students and the lecturer. Finally, it would be fair to say that students have most definitely benefited from reflecting upon their own learning and that of others and through self and peer assessment have focused their minds on aspects they might not have otherwise considered, but are very important to future employability. D:\219547184.doc 7 References Biggs, J. (1999). Teaching for quality learning at University. London: Open University Press. Burgess, H. (1999). Self assessment in Professional and Higher Education. Retrieved August 2, 2006 from http://www.swap.ac.uk/learning/Assessment2.asp Collier, K. G. (1980). Peer group learning in higher education: the development of higher order skills. Studies in Higher Education, 5(1), 62. Falchikov, N. (1995). Improving feedback to and from students. In D. Boud (Ed.), Assessment for Learning in Higher Education (pp. 157-166). London: SEDA/Kogan Page. Gross-Davis, B. (1993). Tools for teaching. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Harris, D. & Bell, C. (1990), Evaluating and Assessing for Learning. London: Kogan Page. Heron, J. (1981). Assessment revisited. In D. Boud (Ed.), Developing Student Autonomy in Learning. London: Kogan Page. Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R.T., and Smith, K.A.(1993). Cooperative learning: increasing college faculty instructional productivity. In B. Gross-Davis, Collaborative learning: group work and study teams (pp.1 – 10). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Kernaghan, A. (n.d.). Is the Reflective Practitioner Model an Impractical Theory? Retrieved July 4 2006, from http://www.qub.ac.uk/schools/EssentialSkills Kohn, A. (1986). No contest: the case against competition. London: Houghton Mifflin. Mowl, G. (1996). Innovative Assessment. Retrieved July 3, 2006, from http://www.city.londonmet.ac.uk/deliberations/assessment/mowl_content.html Mowl, G. (1996). Innovative Assessment. Retrieved July 3, 2006, from http://www.lgu.ac.uk/deliverations?assessment/mowl_content.html Race, P. (1995), What has assessment done for us – and to us? In P. Knight (Ed.), Assessment for Learning in Higher Education (pp. 61-74). London: SEDA/Kogan Page. Race, P. (1995). The art of assessing. New Academic, Autumn 1995, 3-5. Retrieved July 3, 2006, from http://www.lgu.ac.uk/deliberations/assessment/artof_fr.html Schon, D.A. (1988). Educating the Reflective Practitioner. Presentation to the 1987 meeting of the American Educational Research Association (pp. 1 – 15). Updated November 2000. Russell: Queens University, Ontario. Retrieved from http://educ.queensu.ca/~russellt/howteach/schon87.htm D:\219547184.doc 8