Durban II: “Flip the Script” Short Version

advertisement

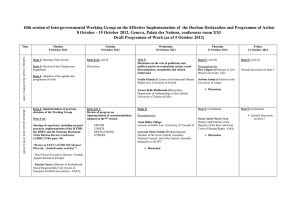

Durban II: “Flip the Script” Short Version1 Fernne Brennan©, Senior Lecturer in Law Human Rights Centre, University of Essex April 2009 Introduction The Durban Review 20-24 April 2009 (Durban II)2 provided an opportunity for Member States to tell the United Nations and the world what they had done to implement the Durban Declaration and Program of Action 2001 (DDPA), adopted following the World Conference Against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance.3 This dialogue was pursued through State and NGO representation at the Palais des Nations, Geneva, Switzerland and through the formulation of a draft ‘Outcome Document’.4 This document collates a number of matters. It seeks to review progress and consider the implementation of the DDPA,5 to assess “the effectiveness of the existing Durban follow-up mechanisms,”6 to promote “the universal ratification and implementation of the International Covenant on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination,”7 and consider the work of the Committee,8 to give consideration to “best practices achieved at the national, regional and international levels in the fight against racism,” 9 and to deal with the “identification of further concrete measures and initiatives at all levels for combating and eliminating all manifestations of racism and racial discrimination.”10 1 I would like to extend my thanks to the Centre for Housing Rights and Evictions for enabling me to attend this historic occasion, in particular to Mr Salih Booker (Executive Director) for his timely advice on the matter of reparations and the World Conference and to Ms Coleen Gooding-Petit (Executive Assistant) for her help in securing my access to the conference. A longer version of this paper is in preparation for publication. 2 Durban II refers to the Durban Review Conference, 20-24 April 2009, Geneva. 3 Also known as Durban I. 4 See General Assembly, A/CONF.211/L.1, 24 April 2009, Adoption of the Final Documents and the Report of the Durban Review Conference, http://www.un.org/durbanreview2009/pdf/Draft_Report_of_the_Conference.pdf 5 Ibid., section 1. 6 Ibid., section 2. 7 Ibid., section 3. 8 Ibid. 9 Ibid., section 4. 10 Ibid., section 5. 2 The various opinions that surfaced from government and non-governmental organisations attested to the tensions between rhetoric and action. One particular example of this dichotomy was raised by the Hon. S. D Blackett, Minister of Community Development and Culture (Barbados). Referring to Paragraph 158 of the DDPA, that gives historical recognition to the marginalization of Diaspora societies and calls for redress by way of social and economic development,11 he noted the gap between text and the failure to give concrete effect to this measure. Despite the very positive work carried out since Durban I by some National Human Rights Institutions (NHRIs) such as the Equality and Human Rights Commission UK (EHRC),12 there was criticism of the paucity of concrete measures. This was especially acute amongst those NGOs who argued that there was much work to be done to address the legacy of the Transatlantic Slave Trade. 13 Although they supported the adoption of the Outcome Document14 these NGOs argued that the scripting of Durban II needs to be ‘flipped’ in preparation towards Durban + 10.15 This should include implementation of DDPA with respect to slave trade legacy issues and the establishment of a Permanent UN Forum on People of African Descent.16 Perhaps some of the most innovative work to come out of Durban II with respect to the issue of the slave trade legacy was the focus on reparations as “development”. This report concludes with the suggestion that the notion of development provides a useful and more palatable focus for scholars with an Article 158 of the DDPA states, “Recognizes that these historical injustices have undeniably contributed to the poverty, underdevelopment, marginalization, social exclusion, economic disparities, instability and insecurity that affect many people in different parts of the world, in particular in developing countries. The Conference recognizes the need to develop programmes for the social and economic development of these societies and the Diaspora, within the framework of a new partnership based on the spirit of solidarity and mutual respect…” 12 Equality and Human Rights Commission, Commission supports global call to end discrimination at UN anti-racism conference, http://www.equalityhumanrights.com/en/policyresearch/hrsubmissions/pages/unantiracismconference.aspx. 13 December the 12th Movement International Secretariat, the Global African Congress, the International Association Against torture, the National Conference of Black Lawyers and the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America. 14 See General Assembly, A/CONF.211/L.1, 24 April 2009, Adoption of the Final Documents and the Report of the Durban Review Conference, http://www.un.org/durbanreview2009/pdf/Draft_Report_of_the_Conference.pdf 15 The term ‘Durban+10’ is reference to a future World Conference Against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance. 16 See Global African Congress and the December 12th Movement (Joint Statement) http://www.un.org/webcast/durbanreview/archive.asp?go=090423 11 3 interest in human rights education that seeks to address the call for reparations for the Transatlantic Slave Trade (TAST) as a way of addressing the legacy of racism faced by Diasporan Afro-descendants. The Script The World Conference Against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance (Durban I – 2001) has been hailed as a victory for the focus it gives to racism and related intolerance as a global problem that requires global solutions moulded to deal with particular instances at the local, national, regional, cross-border and international levels.17 Out of that conference was produced the DDPA. It is a historic document and a major achievement of the UN to obtain political consensus from sometimes diametrically opposed constituencies. It is clearly no mean feat to get Member States of the UN 18 and NGOs to agree on the text of a general declaration that sourced racism and its contemporary consequences, sought to identify the victims of racism, xenophobia and related intolerance, and consider strategies to achieve racial and related equality by way of a programme of action. This includes the monumental achievement to give international recognition to the Transatlantic Slave Trade as a source of racism today19 and to consider reparations for the consequences of this trade.20 For the advocates and critics of slave trade reparations alike, the DDPA provided a means through which to consider the issues of slavery and its vestiges – colonialism, genocide and apartheid and its consequences for Diasporan Afro-descendants. Never before have these issues with respect to reparations 17 Mary Robinson, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and Secretary-General of the World Conference against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance, Foreword, DDPA (2001). 18 As of 2006 there were 192 Member States of the UN, see General Assembly, GA/10479, at http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2006/ga10479.doc.htm 19 See paragraph 13, page 16 of the DDPA (2001). 20 Paragraph 158 of the DDPA (2001). 4 “been placed before an international governmental body including countries who were directly involved in the slave trade.”21 Durban II With respect to discussions about the Transatlantic Slave Trade and reparations; two quite contrasted positions presented themselves during the dialogue between NGOs and government representatives at Durban II. There were voices that considered the Durban Review to be an unmitigated disaster. A number of reasons were given. It appeared, like Durban I, to have been dominated by concerns over the Middle East conflict, in particular, the conflict between Israel and Palestine and the views from the Iranian Government. Indeed, the press were full of stories condemning the Iranian President’s statement regarding Israel 22 and showing in graphic detail the number of seats made vacant by some who had walked out of the assembly hall in protest at what was said by the Iranian President. It was made clear, however, that ‘walking out’ was a legitimate way to express discontent at the opinion of speakers. It could also be argued that having listened to the speeches of a number of Member States very little had been done in the 8 years since Durban I to implement the DDPA. Indeed there seemed to be some sentiment with the view that the UN is not capable of delivering more than rhetoric went it comes to making its ideas concrete. This is because it has to rely on the good faith of Member States to make good their commitments made at international level, and that there is very little by way of ‘carrot’ or ‘stick’ to get States to move from text to action. This view was portrayed by some with respect to the call for reparations for the Transatlantic Slave Trade. 21 A. Santana, Durban 400: The United Nations World Conference Against Racism and the Case for Reparations, a documentary on DVD produced by the Drammeh Institute, Inc and Al Santana Productions, 2003. 22 A. Callamard, Durban II: Now for the Legacy, Guardian.co.uk, 27 th April 2009, http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2009/apr/27/durban-racism-conference 5 In the Press Room of the UN, for example, NGOs were questioned about the call for reparations23 following their press statement entitled African Diasporan NGOs Declare Durban II “Outcome Document” A Victory.24 The main question asked by the press was for the NGOs to respond to the fact that the Outcome Document did not refer to reparations, that the DDPA was a document most people did not know about and that finding money for reparations was not feasible. NGOs replied that the Outcome Document specifically affirmed the DDPA. Indeed, the Draft Outcome Document25 “Reaffirms the Durban Declaration and Programme of Action (DDPA), as it was adopted at the World Conference against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance in 2001.”26 Filtering the messages of the DDPA to the general population was a question that should be addressed to Member States. Some States had actively engaged in dealing with the DDPA. For instance in Bolivia and Brazil census questions had been designed to take account of Diasporan Afro-descendants.27 This in itself is of major importance because if a group is not recognised, it does not count and is likely to fail to be reflected in government policies aimed at reducing inequalities and its causes. The Mexican and Turkish Governments have begun to look at issues of migration in the context of the DDPA. In the USA the disclosure legislation has provided opportunities for companies to give information regarding their involvement in slavery. 28 Furthermore, the public discourse in the UK and elsewhere around The Zong29 has opened up the possibility of discussing the potential 50 million bones of African people at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean who have not had a decent burial – a testimony to the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Moreover, the question of type of reparations ‘payable’ should not be reduced to a dollar amount. That only serves to commodify human suffering. The On the 23 April 2009 there was a number of NGO’s present a the press conference including the December 12 th Movement International Secretariat, the Global African Congress, the International Association Against Torture, the National Conference of Black Lawyers and the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America. 24 A statement was circulated at the press conference. 25 Also known as Draft Outcome Document Rev 1. 26 Section A, part 1 of the Draft Outcome Document Rev 1. 27 On Afro-Bolivians the UNHCR reports on the discrimination they face in Bolivia. However, since 2007 they have been recognised by the state as constituting a legitimate minority ethnic group, see http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/type,COUNTRYREP,,BOL,49749d527,0.html 28 See Iowa Insurance Division, Consumer Affairs Bureau, Report on Slavery Era Insurance, at http://www.iid.state.ia.us/educational_materials/slavery.asp 29 http://wilberforce.1kit.com/1kit/SlaveShip/TheZong/tabid/3799/Default.aspx 23 6 issue was about repair and this needed to be reflected in policies that would address education, health, the criminal justice system and other legacies of the TAST. A number of representatives from the press30 asked questions about the way forward. It was suggested that several matters could be dealt with leading up to Durban+10: To encourage States to report on their own goals and objectives in dealing with the DDPA; to encourage African States to support CARICOM31 in its endeavours with respect to slave trade-based reparations; to make links with the Global African Congress32 that is making inroads in this area; and to ensure that by Durban+10 the United Nations has a Permanent UN Forum of People of African Descent. ‘Flipping’ the Script Mr. Doudou Diène, former Special Rapporteur on Contemporary forms of Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and related intolerance for the United Nations advised the UN Human Rights Council in his report of February 200833 that racism is on the rise all over the world expressed in individual acts of aggression, extreme right-wing group propaganda and “political trivialization and democratic legitimisation of racism and xenophobia.”34 30 Furthermore, “the intellectual legitimization of racism, The RMT (UK), the Chicago Bulletin and the Oklahoma Post. African Diaspora Wants CARICOM to Pursue Reparations Agenda for Slavery, Caribbean Community (CARICOM) Secretariat, Jointly organized by the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), the African Union, (AU) and the Barbados Commission for Pan African Affairs. The African Diaspora Global Conference advocated for the establishment of an AUCARICOM International Reparations Commission comprising government and civil society representatives to study the issue of reparations and repatriation in a scientific and comprehensive manner, with a view to proposing credible options for reparations. The Conference also urged the AU and CARICOM to act on the Plan of Action of the United Nations World Conference against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance, held in Durban, South Africa in 2001, by also establishing a High-Level Panel of Eminent Persons from the AU, CARICOM and other African Diasporas, to lead follow-up action. The Conference held on 27-28 August under the theme, Fostering Sustainable Global Dialogue with Africa and its Diaspora: The Case of the Caribbean was organised in the wake of the observance of the 200th Anniversary of the Abolition of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade and in the context of the Bicentennial Global Dialogue on ‘Slavery, the Slave Trade, Reconciliation and Social Justice.’ at http://www.caricom.org/jsp/pressreleases/pres202_07.jsp 32 The Global African Congress is a grass-roots forum that emerged after Durban I (2001) and the Barbados Conference (2002) , M. T. Martin and M. Yaquinto, Redress for Historical Injustices in the United States (Duke University Press, 2007), p.433. 33 General Assembly A/HRC/7/19, 20 February 2008. 34 Ibid. 31 7 xenophobia and intolerance [is] another worrying trend.”35 The former Special Rapporteur noted the pivotal place “of the historical and cultural legacy of racism in the collective subconscious” 36 and considered the “cultural and historical processes shaping all forms of racism.”37 He suggested that “the Durban review process should provide the opportunity for the international community to express its political commitment to assess these [developments]…”38 and it should help to revise a programme that takes account of these problems. In addition to these views were those expressed at the conference from the representatives of Guyana and Cuba. Mr Patrick Gomes, representing Guyana, with support from Barbados, Jamaica, Haiti and Surinam, suggested that the reaffirmation of the DDPA was a positive step, however the major issue of reparations and compensation for the TAST was one that needed to be addressed. He said that the TAST was a crime against humanity and that the descendant victims deserve recognition.39 The representative of Cuba, H.E. Mr Rafael Bernal Alemany, First Deputy Minister of Culture, said that the TAST was a crime against mankind and that for the descendants of those crimes reparations and compensation was long overdue.40 The question is then how we in the field of education address these questions? The issue is whether we as educators in Britain have an obligation to consider the question of reparations for the TAST. The DDPA which has been affirmed at Durban II informs us that we have and that this is more than a consideration. In the section of the DDPA that deals with national processes, paragraphs 117-120 refer to ‘Education and Awareness-Raising Measures’. In particular we are asked to work-in the subject of the marginalization of Africa’s contribution to world history41 and to build on the 36 Ibid. Ibid. 38 Ibid. 39 Durban Review Live Webcast, http://www.un.org/webcast/durbanreview/archive.asp?go=090423 40 Durban Review Live Webcast, http://www.un.org/webcast/durbanreview/archive.asp?go=090421 41 Paragraph 118 of the DDPA. 37 8 Slave Route Project of the United Nations Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO)42 which has a theme focused on “breaking the silence” about the slave trade and its consequences.43 It is time we as legal and human rights educators “flipped” our own script. We should begin to build the story of the TAST and its legacy into the work we do as human rights educators with our students, scholars and others. Historians and other scholars are adept at doing this44 and American scholars have an excellent track record in this area with respect to America and its part in the TAST.45 The matter cannot be left to history alone, nor should we source our own knowledge in the work of American scholars. We have an educational obligation to look at the British Slave Trade, Slavery in British colonies, links with other western colonial powers such as France and Denmark. UNESCO has begun to pursue this work.46 Such research enables us to source the roots of racism and racial discrimination in a past that has continuing and current consequences for many of our fellow citizens. Historically sourced discourse on the TAST and its consequences provides human rights educators with a firmer grounding upon which to consider the content and application of measures aimed at eradicating racism in the public and private domain. Such work gives fresh impetus to issues of law, justice and human rights. These are also contemporary issues sourced in problems that were not eradicated with the invention of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the development of the International Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination, or the European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms and subsequent instruments. We need to design projects that enable us to engage with others to help deliver the concrete goals of the DDPA. With our expertise we could focus on development. Development takes many forms – economic, social and legal, for example. These relate to questions of social, economic and political rights, the right not to be discriminated against and the right to participate in decision-making through effective 42 Paragraph 119 of the DDPA. Ibid. 44 See the Wilberforce Institute for the Study of Slavery and Emancipation at Hull University. 45 See for example the excellent scholarly work at Hull University’s Wilberforce Institute at http://www.hull.ac.uk/wise/ 46 The Slave Route, UNESCO, see at: http://portal.unesco.org/culture/en/ev.phpURL_ID=25659&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html 43 9 implementation of minority rights and the notion of gender-mainstreaming. When we consider the right to health, the right to fair treatment in the criminal justice system, fair treatment of ‘immigrants’, fair trade with developing countries, and corporate social responsibility, how often do we shape the narrative in terms of development that takes account of the call for reparations? Who do we engage with to help us figure out how we might address these questions in the delivery of our work as scholars and educators? Durban II was a place where many battles were lost but serious questions continue to form the substance of on-going dialogue that the Human Rights Centre and the School of Law at the University of Essex are well-equipped to engage with. It is my desire that by Durban+10 we can be seen to be making a more specific contribution to this very troubling part our educational landscape and the struggle for human rights and justice for all.