New Life in a Death Trap (excerpts)

advertisement

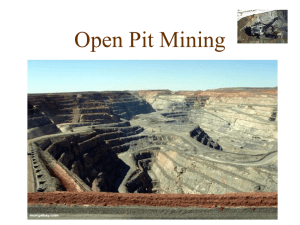

New Life in a Death Trap (excerpts) By Edwin Dobb from Discover Magazine, 2000 Pity the snow geese that settled on Lake Berkeley as a stopover one stormy night in November 1995. The vast lake, covering almost 700 acres of a former open-pit copper mine in Butte, Montana, holds some 30 billion gallons of highly acidic, metal-laden water— scarcely a suitable refuge for migrating birds stalled by harsh weather. So when the flock rose up and turned southward the following morning, almost 350 carcasses were left behind. Autopsies showed their insides were lined with burns and festering sores from exposure to high concentrations of copper, cadmium, and arsenic. Today one need only stand on the viewing platform and look at the pit— the lifeless yellow and gray walls that stretch for a mile in one direction and a mile and a half in the other and the dark, eerily placid lake— to see that it's hostile toward living things. Surely nothing could survive these perilous waters. But in 1995, the same year the birds died, a chemist studying lake composition retrieved some rope coated with brilliant green slime and took it to his colleagues at Montana Tech of the University of Montana, an institution locals proudly call the Tech. Having evolved in partnership with one of the world's richest and longest-running mining districts, it remains a world-class engineering and mining school. Grant Mitman, one of just three full-time biologists on the faculty, quickly identified the slime as a robust sample of singlecelled algae known as Euglena mutabilis. Life had somehow established an outpost in the liquid barren that is the Berkeley Pit. Lake Berkeley was born of human appetite and geological happenstance. During the early 1880s, just as electricity was lighting up cities and the need for copper mushroomed, an ambitious prospector named Marcus Daly discovered an enormous deposit of the red metal 300 feet down in his own Anaconda Mine. For the next 50 years, Butte provided a third of the copper used in the United States and a sixth of the world's supply— all from a mining district only four miles square. Thereafter the "Richest Hill on Earth," as journalists often referred to the place, continued to yield vast amounts of metals. After the Second World War, the shafts grew deeper— one company eventually dug a full mile beneath the surface— but the quality of the ore diminished. Mining officials decided to switch from labor-intensive and dangerous underground operations to open-pit mining, a more efficient method for extracting low-grade ore. Excavation began in 1955, and soon the pit became the world's largest truck-operated mine, along the way displacing some Italian and Serbo-Croatian neighborhoods that had grown up around the original mines on the east end of town. Mining came to a halt in the early 1980s, as did the pumps that had been sucking groundwater out of the mines for a century. The flooding began. Stroll across the mining landscape of Butte today and you will discover why the water has had such a profound environmental effect. The land is dull ocher, and the air smells like rotting eggs. If you look closely at the waste rock, you will see pyrite crystals— fool's gold— everywhere. These are all signs of sulfur. The bedrock is shot through with it. When exposed to air and water, long-buried sulfide minerals produce sulfuric acid, which also helps dissolve other minerals from surrounding rock. Acid-tolerant bacteria that thrive on iron and sulfur compounds hasten this process, and when the pumps were shut down, the Berkeley Pit became an immense chemical transformer producing ever-greater amounts of toxic soup. Making matters worse, it's self-perpetuating. By all accounts, groundwater will continue to migrate into Lake Berkeley indefinitely. Because of this threat to the community, the Environmental Protection Agency added the pit to the federal Superfund list in 1987. The designation also made it part of the country's largest complex of Superfund sites— a series that includes a good part of Butte and the upper 120 miles of the Clarks Fork River watershed.