Document 17925814

advertisement

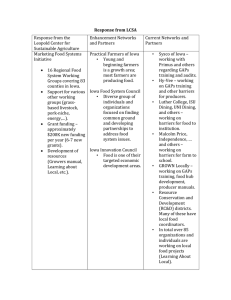

Organizing strategies for new immigrants in Iowa and the midwest Jan L. Flora Extension Community Sociologist Iowa State University Race/Hispanic Origin: Iowa Change 2000-2006 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 -5 Change in Thousands iv at an ic fr o in te at hi /L W c s ni ce pa ra is e H or m or 2 an an eric si m A A an e ic er m N A A Contribution of Immigrants to Iowa’s Population, 2000-2006 Analysis of U.S. Department of Labor statistics points to a deficit of available workers of at least 178,000 in Iowa by 2014. From 2000 to 2006, 41,500 more people left Iowa for other parts of the United States than arrived from other states. Had it not been for a net positive balance of 36,000 people arriving from other countries during those six years, Iowa would have had a serious shortage of workers. The worker shortage will only grow as more boomers reach retirement and fewer young people enter the work force. Immigrants fuel population growth Seven non-metro Iowa counties avoided population loss from 1990 to 2000 due to Hispanic growth (New Patterns of Hispanic Settlement in Rural America/RDRR-99, Economic Research Service/USDA, May 2004). New Iowans and their children fill empty storefronts with their businesses, purchase or rent homes, make our rural downtowns prosperous once again, and sometimes help avoid closure of rural and central-city schools due to lack of students. % Minority Enrollment 1990 Iowa 5.5 % 0 - 4.9 % 5.0 - 9.9 % 10.0 - 14.9 % 15.0 % + % Minority Enrollment 2000 Iowa 9.4 % 0 - 4.9 % 5.0 - 9.9 % 10.0 - 14.9 % 15.0 % + Immigrants pay taxes. Undocumented immigrant families pay substantial amounts of state and local taxes – between $40 and $62 million each year. Employers in Iowa contribute an additional $1.8 million to $2.8 million in state unemployment insurance premiums on behalf of their undocumented employees and contribute annually an estimated $50 million to $77.8 million in federal Social Security and Medicare taxes from which those undocumented workers will never benefit. Iowa Policy Project, October 2007. Immigrants can help make the social security system solvent Immigrant families are younger than the Iowa (and the nation’s) population as a whole. If we make immigrants unwelcome, once Boomers have retired there will be few persons in the workforce to pay into the Social Security fund. Comprehensive immigration reform at the Federal level is essential, but in the meantime, making immigrants (authorized and unauthorized alike) more insecure leads us away from, not toward, a solution. The cynical view—keep them illegal, so they will pay into social security without ever benefiting from it. Majority* Population Pyramid 2000 Iowa Females 85+ 75-79 65-69 55-59 45-49 35-39 25-29 15-19 5-9 6% 5 Males 4 3 2 *White race only, Not Hispanic 1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6% Hispanic* Population Pyramid 2000 Iowa Females 85+ 75-79 65-69 55-59 45-49 35-39 25-29 15-19 5-9 6% 5 *Of any race Males 4 3 2 1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6% IOWA’S NEW FARMERS A study of farming roots and aspirations among immigrants from Latin America Hannah Lewis, North Central Regional Center for Rural Development Iowa State University hlewis@iastate.edu Research Method: Surveys We explored experience and interest in farming among Latino immigrants with farming experience Spring 2006 50 respondents in Marshalltown Spring 2007 61 respondents in Denison Survey results: percent Agricultural aspirations 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Latino want to farm want to garden already garden percent 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 enough time access to land tech skills getting insurance finding mkts access to capital Survey results: Largest Perceived Obstacles Latino Key findings: interviews of Mexican farmers in Iowa (Hannah Lewis) o o o o Respondents are: farming on small acreage (10-20 acres), and raising vegetables, fruits and livestock for sale and home consumption Combining various o Pluriactive farming (combining resources to part-time farming with off-farm purchase land work) helps households achieve Marketing specialty economic and quality-of-life goals products to other • Livestock are central to their Latino immigrants enjoyment of farming (cultural Utilizing skills and capital) knowledge gained in State's dairy farmers turn to Hispanic workers To learn more about their employees as people, the Youngs [Maurie and Rita, Plainview, MN dairy farmers] also signed up for a trip to Mexico. . . There they met the families of some Minnesota farm workers, in poor villages. The experience was humbling, the Youngs said. The Youngs say their transition to foreign workers has been smooth, partly because they had participated in a foreign-exchange program earlier and because they found a terrific bilingual chief herdsman. Minneapolis Star Tribune, Sept. 03, 2007 State's dairy farmers turn to Hispanic workers (Minneapolis Star Tribune, Sept. 03, 2007) Likewise, that herdsman, a soft-spoken young man named Javier Martinez, can't say enough about his new work. "I grew up with animals, and I love working with cows," said Martinez, who does everything from caring for newborns to assisting the veterinarian to overseeing the labor on the farm. "And I love small towns. Here, we can wake up and see the sun. State's dairy farmers turn to Hispanic workers (Minneapolis Star Tribune, Sept. 03, 2007) In the farm-dotted countryside of southeastern Minnesota where the Youngs live, the seeds for hiring Hispanic workers were planted by John Rosenow, a Wisconsin farmer about 30 miles east of Wabasha. Rosenow said he and his wife had been working on their farm about 90 hours a week for 10 years, when they decided they couldn't stay on the treadmill. He somewhat reluctantly checked into hiring Mexican workers in the mid1990s. "It's not natural for [farmers] to hire someone from another country, another culture, another language," he recalled. "There's been nothing but Swiss and German people here for 150 years.... But then you realize it's the best thing you can do." State's dairy farmers turn to Hispanic workers (Minneapolis Star Tribune, Sept. 03, 2007) Rosenow's workers were so reliable that other farmers took notice, he said. The otherwise low-key Wisconsin farmer found himself becoming an unpaid employment agent, helping about 100 farmers find Hispanic labor over the past decade. He relied on the contacts of his top Mexican employees. "I'd get calls from farmers in Wisconsin, Minnesota, North Dakota and Iowa, saying they couldn't find workers," Rosenow recalled. "I'd explain [to his worker] what we needed, and typically he could find someone by the next day. The networking was incredible." Rosenow and [Shaun] Judge Duvall were vital in creating Puentes/Bridges, an organization designed to smooth over cultural misunderstandings between the newest farm workers and the longtimers. The organization, based in Alma, [WI] is bringing another batch of farmers to Mexico in November and helping sponsor a community forum in nearby Arcadia, Wis., this month. Hannah Lewis—Dairy workers in Iowa New dairy workers invariably start in the milking parlor and are trained on the job by experienced workers. If they show promising skills, they can begin to take on more responsibility and some may climb an internal job ladder. Job titles include head herdsman, head of maintenance, feed manager, etc., depending on farm size. There may also be assistant positions. Farmers who hire Hispanic workers have a bilingual employee in a lead/supervisory role. Bilingual staff is also responsible (on the larger farms) for filtering and hiring and training new applicants. 3.) Recruitment takes place mainly by word-of-mouth among employee networks. These workers come with all documentation, but farmers do not necessarily know whether it is legal documentation or not. Hannah Lewis—Dairy workers in Iowa These six farmers say that looking to the local Anglo population for a labor supply is a dead-end path; they are completely dependent on immigrant labor. They would like to see immigration policy that allows immigrants to live and work in the U.S. legally. Training: Several farmers conduct periodic trainings/refreshers for established workers to reinforce the key point that the quality of the work in a dairy farm has a direct effect on the quality of the milk. These trainings are generally in the form of a bimonthly luncheon. Sometimes guest presenters are brought in, such as Alvaro Garcia from U of SD or bilingual presenters from Monsanto or Phizer. Farmers don't rely on written protocols since all information and knowledge is passed on through showing, doing and explaining. Lewis--Dairy farmers mentioned following labor concerns that Extension might address: Explain farm labor law requirements (workman’s compensation, etc.); Help organize chore relief for smaller farmers to attend Extension seminars; Help recruit summer interns onto farms (to cover employee vacation time); Prepare dairy students to become future dairy managers with more practical skills and on-farm internships opportunities. Conduct farm safety training; Provide language assistance on smaller farms with no bilingual employees; Educate general public to dispel negative myths about immigrants to build support for immigration policy that allows a stable reliable ag workforce. Explain details of guest worker programs, parameters and how to enroll; (Note: several farmers stated that it is not much help on a dairy farm to hire seasonal workers. Not only is dairy year-round work, but several dairy jobs are high-skilled and learned over time.) The “DAIRY AIR” Program Breathing New Life into the NE Iowa Dairy Industry Sharemilking is a contractual arrangement between a landlord/employer and a tenant/ employee that combines the management, labor, cattle and/or machinery in a multi-party dairy enterprise without a more formal arrangement such as an LLC, partnership or corporation. The overall goal is to build career bridges for beginning, mid-career and retiring farmers. The “DAIRY AIR” Program Stage 1: Hired and/or Intern Labor Prospective sharemilker works side by side with producers to learn day-to-day dairy management. Stage 2: Working for a Percentage Wage After building trust as an employee, the relationship can build to receiving increased incentives based on milk price premiums and assuming risk in the ups and downs of milk prices. Providing the milking, feeding, manure scraping, calf and herd health roles for 10%-20% of the milk check is common. Phase lasts about a year and is a good “testing” time to see if parties are compatible for advanced sharemilking. The “DAIRY AIR” Program Stage 3: Owning Cattle Cattle ownership. This is accomplished by outright purchase or lease of new or existing herd animals by the sharemilker. Ownership of 10%-20% is often a good first step. The sharemilker is often compensated for their investment in the herd either by an increased percentage of the income, assistance in the cost of raising their heifers, etc. Contractual arrangements are increasingly important from this stage onward. Stage 4: Sharing of Income and Expenses The sharing of expenses can begin in any of the above stages as it goes hand- in- hand with the varied ways of sharing income. An overriding goal of this sharing is “fairness” as an unfair sharing often invites its own destruction. Thus, it is in the interest of both parties to do what’s fair, which often may go against the custom of the community from past sharemilking arrangements. Building Capacity to Engage Latinos in Local Food Systems in the Heartland North Central SARE Professional Development Program March 21-22, 2007 NC SARE PDP -- Grant Recipients Meeting -- Chicago Activities 2 multicultural trainings on working w/ Latino families 4 experiential learning visits Eight one-day trainings in Local Food Systems Facilitated planning session for professional leadership Outcomes Increased awareness of Latinos as valued community members and current/future farmer Improved skills in engaging Latino audiences w/ culturally appropriate programs Improved understanding and skills in assessing, analyzing and gaining resources for Local Food Systems Improved understanding, skills in marketing and business development strategies appropriate to LFS Ability to integrate knowledge, skills described above to develop strategy for sustained support programs Marshalltown Farmer Entrepreneurship and Local Food System Marshalltown Community College Entrepreneurial and Diversified Agriculture and farmer incubation program Growing Food and Profit El Colectivo & Latinos en Accion Key elements in place in Marshall County Many farmers and resources to grow new farmers Farmers’ market Emerging intercultural network of farmers and eaters (Growing Food and Profit) Lots of independently owned food businesses; several with interests in local foods Marshalltown Chamber “Target 5” campaign to encourage local sourcing Local culture of interagency collaboration (example: Community plan for another possible ICE raid) Slow Foods movement beginnings Regional Food Systems Working Group (Leopold Center) and Prairie Rivers RC&D as support group Marshalltown Hispanic Small Businesses 42 Registered, Operating Hispanic Businesses… and counting 55 Total… and counting Business Types Number of Businesses Retail Services* (clothing, others) 16 Auto Repair, Tires, and Towing 10 Restaurants 9 Food Products (“groceries”) and Services* 6 Entertainment, dancehall 4 Construction and Painting 3++ Food Products and Bakery 2 Laundromat 1 Auto Insurance Provider 1 Hair Stylists and Barbers 0 Hotel/Motel 0 Other (bands, healers, auto dealerships, etc.) 3++ Total 55 *e.g. money transfer, translation, tax preparation ** Total is more than 100% due to rounding. % 29 18 16 11 7 5 4 2 2 0 0 5 99** Start-up Characteristics Where do business owners come from (n=18)? - - Mexico, Jalisco Mexico, MIchoacan Mexico, Zacatecas Mexico, Guerrero Mexico, Puebla Mexico, Guanajato Cuba, Havana 6 3 2 1 1 1 1 Total Accumulated Start Up Investments (n=14) Utilized personal savings and/or family loans Applied for bank loans for start-up/expansion Bank rejected loan application Returned to same bank (or other) and received loan Previous Experience owning a business Developed a Business Plan before starting $1.1M 17 10 6 7 7 0 Sales and Marketing Total Avg. monthly sales (n=11): $265K Total Avg. annual sales (n=11): $3.1M Total Average # of clients (n=12): Weekday: 335 Weekend: 783 Month: 11,802 5 have a business accountant 9 Advertise in English (Print: Penny Saver, Radio) Employment Total employees (n=18): Full time: Part time: 65 46 19 Employing family members: Owner and Operator: Insures employees (n=16): Total Annual payroll (n=13) 13 16 0 $716,600 Expected Outcomes (Systemic Changes) Successful Latino farmers and local businesses engaged in local food systems Sustained institutional engagement in education and technical services in support of Latino farm families Outcomes of ICE raid study Play on the raids experience in Marshalltown based on in-depth interviews)-Plan for responding to raids for other communities—newspaper person. Legalist, pluralist, pragmatist—design a program for education about immigration. Regional project