Medical Student Guide to Surgery

advertisement

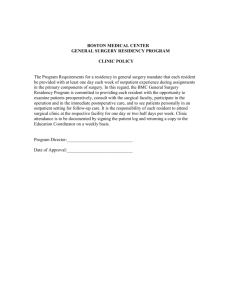

Medical Student Guide to Surgery INTRODUCTION Welcome to your Surgery Clerkship! This rotation can be one of the most memorable experiences of your third year. This may be the only chance you will ever have to see such things as a liver transplant, open-heart surgery, a laparoscopic gastric bypass, a trauma, or even an appendectomy. It can be an unbelievable experience, but we also recognize that it can be quite intimidating. With this guide, we hope to unlock the mystery of surgery and give you some tips on how to excel on this rotation. As faculty and residents, we see this as an opportunity to teach you some basic concepts about surgery that will benefit you regardless of which field you chose to enter. It also gives us a chance to show you how exciting surgery can be and to give you a sense of why we chose it for our own careers. With the help of this guide, we hope to unlock the mystery of surgery, to provide some tips on how to excel on this rotation, and to outline your responsibilities. There are four basic parts to any surgery service: Rounds, the Operating Room, Clinic, and Call. Below you will information to help you find your place and excel in each of these activities. 1. ROUNDS Most surgical teams round twice a day. Surgeons spend the majority of their time in the operating room and clinic. As a result, there are rounds before the day begins to set plans for the inpatients and afternoon rounds to follow up on the day’s events. With that in mind, rounds typically start at 6:30am on weekdays. With cases starting at 7:30, there is no more than 1 hour to round on the entire service, which can be anywhere from 10-30 patients. The only way this can be done successfully is for the team to work together. Teamwork enables us to be efficient and accurate. So, here are some tips to help you be a part of the team and make rounds run smoothly. Presentations: o Each student is generally expected to follow 3-4 patients. You should know everything about why these patients are in the hospital, what their relevant past medical history is, and where they are in the course of their work-up, treatment, and recovery. It is best to follow patient’s whose surgeries you saw or people you saw in clinic who were admitted. Obviously, this cannot take place in the beginning of the rotations, but should be how you pick up patients without residents having to assign them to you. o You will generally be expected to pre-round on your patients. This includes gathering vitals and recent labs and evaluating your patients with a directed history and physical exam. Gathering vital signs and labs for your patients is not scut work. This is something you will be expected to do as an intern in any field you choose to go into, so it helps to start learning efficient ways to do this as a student. o All post-operative patients and patients with abdominal complaints should be asked about pain, nausea, vomiting, flatus, bowel movements, and activity (e.g. have they been out of bed?). If you have questions about what to ask you patients or what physical exam findings are important, talk to the intern or junior resident on your service and they can help give you tips when you are on specialty services. For example, on vascular surgery it is always important to check pulses on your patient. o Present each patient in S.O.A.P. format. Start with a ONE LINE statement about who they are, why they are in the hospital, and where they are in their course. Your presentation should be an update on significant events since the last time the team rounded. It should include a directed history, pertinent physical exam findings (including vitals), and an assessment and plan. o If your patient has never been presented on rounds before (i.e. they are a new patient), give a brief introductory H&P, including relevant PMH and meds. o Vitals are presented as Tmax, Tcur, HR, BP, RR, Sat or pulse ox, and ins and outs, including Urine Output and Drain Output (usually presented as over last 24 hours and over last 8 hours). o Try to review new labs prior to presenting. Knowing trends is important (e.g. is the WBC increasing or decreasing?). o A directed physical examination should include the heart, lungs, abdomen, surgical wound, extremities. Although you should definitely examine all of these areas, you may be asked to only present the most relevant on rounds. o Know diets, antibiotics, cultures, and IV fluid status for all of your patients. o NEVER use terms if you don’t know what they mean. This means if your patient has a diagnosis you don’t understand, has had a procedure with which you are not familiar, or is on a medication you haven’t heard of, then you should look them up or ask someone before rounds. o Morning presentations are usually short, shoot for 1-2 minutes. In the beginning yours may be longer but you will learn to edit. General Tips: o Dress professionally for rounds; only wear scrubs when you are post-call. o Be on time and ready to go when the chief arrives. o Surgery is all about teamwork so help the team gather charts, door books, and MARs (inpatient daily medication administration records), if necessary. o Try to be brief and organized. Follow the S.O.A.P. format to keep organized. o If you are not presenting, help take down/change dressings. o Carry some dressing supplies with you such as scissors, gauze, and tape. o Pay attention to your colleagues when they are presenting. You are expected to have a basic idea what is going on with all patients on the service. o If there is something you don’t understand, such as a term or a treatment plan, find the appropriate time and ask someone. o Keep everyone informed. If you find out information that you think may be really important, let a resident know right away. There is no need to wait until rounds. For example, if your patient has worrisome symptoms or physical exam findings or a new worrisome test result, mention it to someone before rounds. It may need to be dealt with quickly. This is a very important way that you can contribute to patient care. 2. THE OPERATING ROOM The promised land! This is what your surgical rotation is all about. The OR can provide some very memorable experiences, from seeing rare cases to getting a chance to suture at the end of the case. The key to getting the most out of each case is being prepared. The Teamwork concept is stressed here again. It is extremely difficult to perform a surgery without the appropriate help. This begins from the time the patient enters the OR until the patient reaches the recovery room. There are opportunities for valuable procedural experiences for the medical student. But, as noted above, just being present is not sufficient; you must be prepared to help with the case. So here are a few tips to help you get the most out of each trip to the operating room. Preparation: o Know what case you are going to do the next day! o Divide up the cases amongst the students on the team as early as possible. o Each service has an OR schedule that can help, but you must check the main OR board the night prior and frequently throughout the day to get the most up to date changes. o There will be times when the schedule changes and you end up in cases you hadn’t planned to be in. We understand this, but you need to be flexible and prepare as best you can. o Read about the patients – specifically know their presenting complaints, diagnosis, indication for surgery, and procedure being performed. o Review appropriate anatomy for the case – these are the most popular pimp questions. The Operating Room: o Be on time for each case. You should arrive with the patient or even before. Cases typically start at 7:30, except on Wednesdays when they start at 8:30 because of grand rounds. You are not expected to be on time to the first case as you have class, but you are expected to show up after your lecture. o Try to meet the patient preoperatively in the Pre-Care area o You can leave your pager # for the nurse and ask to be paged when the patient arrives but this is not a guarantee. The nurses have many responsibilities; paging you is something they do as a favor. You need to be diligent about checking on the room and the patient in the holding area. o Wear appropriate attire – scrubs, scrub hat, mask, eye protection, and shoe covers o Always get your gloves out for the scrub nurse/tech. Ask if they need an extra gown for you. o This is a great time for procedures – learn to place a foley, start an IV, prep the patient, etc. Again simply being present may not be enough. If there is something you would like to learn how to do, ASK. o Be attentive during the case – how much you can help is directly related to your being aware of what is going on. o At the end of the case, you can help the resident close and then help get the patient transferred to the PACU – this includes getting the bed, helping move the patient, and learning to write post-op orders and prescriptions. General Tips: o Introduce yourself to the OR staff. o Help the resident position the patient. o Remove your pager before scrubbing. o You are a part of the team. Ask questions and be ready to participate. The team is counting on you and will get you actively involved. o Understand that there is a time for questions and a time to be silent. If the situation seems tense or the team brushes you off, this may mean it is the wrong time for questions. Hold onto your questions, though, and ask them later. 3. CLINICS Each attending/service will have clinic at least one day each week. If you are assigned to a particular attending, you should plan to be in clinic with that attending. If you are not assigned to a particular attending then the chief of the service will direct you as to which clinic you should attend. Clinic is a great opportunity to meet patients preoperatively. It also provides a chance to follow patients through the entire process from preoperative evaluation through to the post-operative visit. General Tips: o Professional dress is required for all clinics. Sometimes you will be unexpectedly needed in clinic, so it is important to bring appropriate attire for clinic to work everyday. o Each attending has preferences. Ask the attending or the residents if they prefer you to see patients on your own or with a resident. o When seeing new patients perform a complete history and physical. You will present a complete H&P to the attending. o When seeing return patients perform a directed history and physical. Limit your interview and exam to the relevant information. o If you don’t know whether or not you should do something (i.e. take down a dressing), ask someone. Don’t just assume you should skip it or assume you should do it. o If the patient you see is going to be scheduled for the OR, ask a resident how you can help with the preoperative paperwork. o Try to be efficient. The clinics are often overbooked and you need to be fast, but thorough. 4. CALL Call is still a very real part of surgical training and practice. Therefore, students will be required to take call during the clerkship. This is a great opportunity to see the urgent and emergent cases that rest at the heart of surgery. This is also a great time to pick up patients for your write-ups. Medical students should not 'hang out' in the call rooms. You have your own designated workroom/call space. The call rooms are located on the 3rd floor of the Patient Support Tower. To get to these rooms you should go to the OR elevators on the 2nd floor, take the elevator to the 3rd floor and look for the coke machine. The on-call rooms and student workroom/lounge are inside the door on the left side of the coke machine. Consult Call: o For general surgery, the Senior In House (SIH) is a 4th or 5th year surgery resident whose primary responsibility is to see consults with a 2nd year surgery resident and to see pediatric and burn consults. This resident also provides back up for all the surgery residents on-call. o The Junior In House (JIH) is a second year resident whose primary responsibilities are to care for the Cardiac Surgery patients and to see general surgery consults. o On consult call, you will see consults first-hand and get a chance to see traumas and emergent cases that are done at night. o Ask questions. Things can be very busy, but this is a great opportunity to learn. This may be your only chance to learn how to evaluate abdominal pain or other potentially surgical complaints. o Take this chance to learn to write admit orders, read radiology studies, workup traumas, etc. 5. GENERAL HELPFUL HINTS The more you show yourself to be interested, the more people will involve you. By asking questions and asking for opportunities to participate, you show that you are interested in learning. People respond positively to this and whether intentionally or not, they will end up involving you more. If you don’t know where you are supposed to be, ask someone. Your residents are always around and can help give instructions or suggestions about where you might learn the most. Remember that we see all 160+ medical students over the course of the year. Sometimes we forget what we have taught to a particular medical student. This is why it is important to ask questions and remind us how we can help you learn. Ultimately, you are responsible for your learning. You are not given a detailed syllabus for third year like you were for first and second year. This does not mean you don’t need to read and study. It simply means you will need to do directed reading. Think about what you do and don’t know well and read to fill in the gaps. Even if you have no interest in surgery as a career, there is a lot to learn on your surgery clerkship. Every type of physician will interact with surgeons in some way. If you have no interest in surgery, figure out what you need to know about surgery for your career and use this to motivate and drive your learning during your surgery clerkship. For example, ask yourself what you need to learn in order to know when to call a surgical consult. Or, ask yourself what you need to know about pre-operative clearance of patients for surgery or management of post-operative surgical complications. Surgeons work closely with many types of physicians. Your surgery clerkship may be your only exposure to many of the smaller subspecialty fields. If you are interested in Pathology or Radiation Oncology or Interventional Radiology or Anesthesia, look for opportunities where you can gain exposure to these fields. For example, if your patient is going for a procedure in Interventional Radiology (VIR), ask if it would be okay if you go watch the procedure. Or, ask if it would be okay for you to follow the specimen to Pathology if one is sent for an intraoperative evaluation. Or, show up early to the case and ask the anesthesia resident or nurse anesthetist if you can shadow them as they prepare the patient for surgery. There may be times when the answer is “No, you are needed elsewhere.” But, more often than not, the answer will be “Sure go ahead.” Ask for feedback on your performance at least once during your rotation. This is another great way to show you are interested in learning. Don’t accept “don’t worry about it, you’re doing fine” as an answer. There are things that even the best clinicians can do to take their learning to the next level. Be prepared, though, when you ask for feedback, you may get some negative feedback. This is not intended to hurt you or put you down. This is intended to be constructive and to help you find ways to improve as a clinician and as a team member. Respect the non-physician staff. The truly successful medical student will quickly learn that everyone involved in patient care can be a valuable resource for learning. Often other staff will have more time for teaching than the physicians. In general, you will find that if you ask, almost anyone will be happy to teach you. Lastly, and most importantly, have fun! 7. IMPORTANT PHONE NUMBERS SIH Pager: 216-4363 JIH Pager: 123-7007 Bed Commander: 123-6650 OR Front Desk: 6-4355 SICU: 6-2181 NSIU: 6-4302 TICU: 6-5246 BICU: 6-3571 ISCU: 3-0727 5BTA: 6-5411 5BTB: 6-5416 5WST: 6-5776 5EST: 6-5616 4AND-N: 6-1943 4AND-S: 6-1952 ER: 6-4721 Stacey: 6-4781