The Phillips curve

advertisement

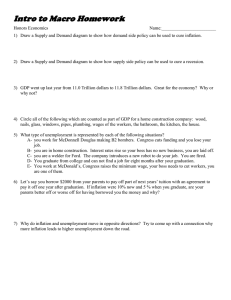

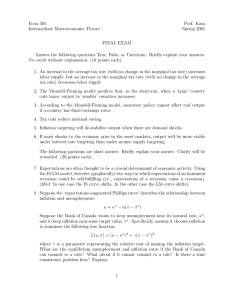

The Phillips curve • In last week’s lecture, we brought the labour market equations into the IS-LM framework and derived the aggregate supply-aggregate demand framework. The advantage of AS-AD over IS-LM is that you can use the AS-AD to talk about prices and unemployment. • A.W. Phillips (a NZ raised in Australia) found a negative relation between inflation and unemployment in the United Kingdom on data from the previous century. Phillips curve in Australia 1960s 6 Inflation rate (percent) 5 1967 4 1969 1964 1968 3 1960 1966 1961 1965 2 1963 1 1962 0 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 Unemployment rate (percent) 3.0 3.5 Moving from prices to inflation • Our labour market equations were in price levels, where here we would like to talk in terms of inflation. Can we put our labour market equations in terms of inflation? • Our labour market equilibrium equation: P = Pe (1 + μ ) F(u, z) • The we “linearize” F(.) by setting: F (u, z) = 1 – α u + z Moving from prices to inflation • So we get: P = Pe (1 + μ ) (1 – α u + z) • This can be rewritten in inflation (π)and expected inflation (πe) as: π = πe + (μ + z) - α u • The derivation is in the appendix for Chapter 8 and is NOT required to know. Simply know that this is only true for “low” levels of inflation. The new labour market equation • Our new labour-market equilibrium condition is: π = πe + (μ + z) - α u – A rise in expected inflation increases current inflation one-for-one. – A rise in unemployment lowers inflation by the amount α. – A rise in the mark-up increases inflation, as do factors, z, that increase the wage-setting term, F(u, z). Policy implications • If this new relation between inflation and unemployment is true, it means that governments had a tool to control inflation. • If governments were willing to raise inflation, they would achieve a lower level of unemployment. • Governments could permanently drive unemployment below the “natural rate of unemployment” by permanently raising inflation. Policy implications • There is an “inflation-unemployment tradeoff”. Governments could “choose” an optimal inflation-unemployment mix along the Phillips curve that best suited them. • Labor governments might choose a tradeoff with lower unemployment. Liberal governments might choose a trade-off with lower inflation. Inflation Phillips curve break-down 18 16 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 -2 0 1977 1983 1993 1970 2 4 6 Unemployment 8 2003 10 12 What caused the breakdown? • The governments assumed that the expected inflation rate, πe, didn’t change. • But the Phillips curve relationship: π = πe + (μ + z) - α u • The y-intercept is πe + (μ + z) and the slope is – α. So any change in πe shifts the Phillips curve relation out. • Governments in the 1970s assumed that the Phillips curve didn’t move. They were obviously wrong. Inflation expectations • So the Phillips curve depends crucially on how people form expectations of inflation. • Let’s say that inflationary expectations are slow to adjust, so: πte = θπt-1 • The we can make this substitution into the Phillips curve equation: πt = θπt-1 + (μ + z) - α ut Expectations πt = θπt-1 + (μ + z) - α ut • For θ = 0, we have a Phillips curve that does not move. For θ = 1, we have the relation: πt - πt-1 = (μ + z) - α ut • So the change in inflation depends on the unemployment rate. • We can also represent this equation in terms of the natural rate of unemployment. Natural rate of unemployment • If inflation is equal to expected inflation, we are at our “natural rate”, so we have: π = πe + (μ + z) - α un • But π = πe, so we can simplify to: 0 = (μ + z) - α un α un = (μ + z) or un = (μ + z) / α • Our natural rate of unemployment is: – Higher the higher is the firm mark-up; and – Lower the greater is the reaction of wage increases to unemployment, α. Natural rate of unemployment • Substituting into our Phillips curve relation for θ = 1, we get: πt - πt-1 = α un - α ut = - α (ut – un) • So if unemployment is lower than the natural rate, inflation will increase by α. • The way to lower inflation is to have unemployment higher than the natural rate. • The only way to keep inflation steady is to have unemployment equal to the natural rate- the non-accelerating rate of unemployment (NAIRU). Policy implications • There is no permanent trade-off between inflation and unemployment, as governments assumed in the 1960s and 1970s. • If the government tries to push unemployment permanently below the natural rate, it will have permanently rising inflation rates. • This is what happened to governments in the 1970s. The Phillips curve kept shifting as inflationary expectations rose.