VETERANS ORAL HISTORIES PROJECT (VOHP),TPS CENTER FOR ORAL HISTORY,

advertisement

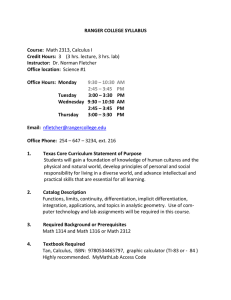

1 VETERANS ORAL HISTORIES PROJECT (VOHP),TPS CENTER FOR ORAL HISTORY, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS TEACHING WITH PRIMARY SOURCES, CALIFORNIA UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA, CALIFORNIA, PA & VETERANS HISTORY PROJECT, AMERICAN FOLKLIFE CENTER, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON, DC INTERVIEWER: JEFFREY L. MORRIS INTERVIEWEE:MICHAEL HUMMEL, PHD MAJOR (RET.), U.S. ARMY (1981-2003) INTERVIEW LOCATION: CALIFORNIA, PENNSYLVANIA INTERVIEW DATE: NOVEMBER 22, 2005 VIDEO: http://tinyurl.com/caluvets JEFFREY L. MORRIS [JM]: Hi, I'm Jeff Morris, conducting an interview for the oral history veteran’s project [i.e. Veterans Oral Histories Project]. My interviewee is Dr. Michael Hummel [MH], who is a[n] [Assistant] Professor of Criminal Justice here at California University of Pennsylvania. JF: Dr. Hummel, how did you decide to get into military service? MH: Well, I think that I had a strong sense…the primary reason, Jeff, is that I had a strong sense of service to our country. My father was a veteran, all my uncles were a veteran, my grandfather was a veteran. I think it was in my genes to continue that service. That was one of the primary reasons that I had to join, and spent the 22 years of military service for our country that I did. JF: Yes, sir. And I noticed on your biography form that you were in the Rangers… MH: Yes, I was. I was a member of the 2nd of the 75th Ranger Battalion that was…that is still stationed out of Ft. Lewis, Washington. I also served as a Ranger Instructor at the United States Army Ranger School, first phase of the course being in Ft. Benning, Georgia. JF: And what kind of training did you undergo as a U.S. Army Ranger? MH: Well, as a…one of the first things you need to do to get into a Ranger Battalion is you [must] complete—successfully complete—a Ranger Indoctrination Program [i.e. R.I.P.]. You go through your basic infantry training at Fort Benning, you go through your basic airborne training, then you volunteer for the Rangers. So you volunteer three times, but [first] have to successfully negotiate and complete a Ranger Indoctrination Program—they call it 2 “R.I.P.” for short, the acronym; that takes care of a lot of people that I think are not really sure if they want to be there or not. Once you complete the three week Ranger Indoctrination Program, then you are authorized entry to the Ranger Battalion, where you work under the auspices and the tight supervision of a Team Leader, a Ranger Team Leader, who then prepares you, through deployments and training in small unit operations, for a Pre-Ranger program, which is a three-week course, back at the time it was a three-week course; it may have changed now, that’s been twenty years ago. [3:15] Once you successfully complete the Pre-Ranger program—and of course go on several deployments and train in several live-fire operations—you can get on the list to go to Ranger School, based on the assessment of your team leader, based on the assessment of you going through the Pre-Ranger program itself. Once you complete that program, you are authorized a slot in the United States Army Ranger School itself, where you must successfully complete the course to be able to be authorized to wear to coveted U.S. Army Ranger Tab. I had did all of this within the year’s time frame, which is fairly unusual—Basic Infantry training, airborne training, Pre-Ranger training, deployment, the Pre-Ranger Program—[i.e.] R.I.P., the Pre-Ranger Program—and then Ranger School. I come in the Army in July and I graduate Ranger School the following June of the next year, which was fairly quick. Some people may stay a little longer in Ranger Battalion—maybe several years—before they are deemed ready to go to Ranger School. I did it fairly quickly. I think it’s all about your attitude; it’s all about your motivation, your enthusiasm, your mental ability to understand what you really want to do, and a strong sense of goal accomplishment. I think that’s the key to success in Ranger School. It’s not for everybody. [4:43] So once I completed Ranger School, I’ve become an effective member—a Fire Team member—in a Ranger unit at 2nd Battalion. I had a great platoon sergeant, great squad leaders. Everybody wanted to be there, everybody was volunteers, everybody was smart people—intellectually sound—very well physical conditioned Americans in the unit. As you progress, just like in any position, and excel at your work through various schools— such as NCO [i.e. Non-Commissioned Officer] professional development schools, various small arms schools—they see your ability to achieve higher levels of responsibility, and 3 accountability, and they send you off to good schools: Special Forces schools: I’ve been to the Jumpmaster’s School, I’ve been to Special Forces Freefall School, the Special Forces Special Operations Training School, Special Forces Freefall Jumpmaster School, and just a lot of other schools at the… [e.g.] the Pathfinder School I’ve been through at Ft. Benning, Georgia, which is a very good school. So the more you excel and the harder you work, the more you can achieve in a specialized unit such as the Rangers. [6:00] But it was all very challenging, academically challenging, very physically challenging, mentally challenging. A great, great sense of teamship. It was one of the greatest experiences of my life and I think one of the greatest achievements of my life. JM: AND AFTER YOUR TRAINING WAS COMPLETE, WHAT KIND OF EXPERIENCES DID YOU HAVE AFTER YOUR TRAINING? Being part of the HALO team, a Pathfinder team, where you jump into a drop zone and setup the drop zone—a lot of responsibilities—set up the drop zone for the rest of the battalion to jump in, or the rest of the company to jump in, the deployments—we were deployed all over the world basically, down into Central America area, a lot of amphibious training down where the buds trained in Corona, California. JM: AND WHAT IS, WHAT IS HALO? MH: HALO is another method of insertion—one of the many—that Rangers use. Ranger Battalions—the “Ranger Regiment” now, that what’s it’s called; there’s three Ranger Battalions—one at the Ft. Stewart, one at Ft. Benning (which is the third)… the first is Ft. Stewart, and the 2nd Battalion is at Ft. Lewis—a method of insertion, then, before it was three battalions, was HALO. HALO is an acronym for “high-altitude, low opening,” where you could exit an aircraft anywhere from up to 29,000 feet to 25,000 feet. We’ve made night jumps using oxygen. It’s a method of insertion—covert type of insertion. [7:47] We also have what you call a HALO operation, which is a, or a HAHO operation, excuse me [i.e.] “high-altitude, high opening,” where you could have a 5 to 7 second delay, and then open your parachute, and you could cruise or cross country from anywhere from 30 minutes up in the air or 30-40 kilometers. It’s another method of insertion that the Rangers use—covert method, a stealthful method of insertion. That's only one of many, but the basics are the same once you get on the ground; it’s a high-speed method of insertion, but once you get on the ground, basic light infantry specialized tactics take place, you know, your sabotage operations, your small unit raids and RECONS [i.e. reconnaissance], and small unit ambushes take place. 4 JM: AND, ALSO ON YOUR BIOGRAPHY SHEET, YOU MENTIONED A CONFLICT CALLED GRENADA... MH: Yes. JM: AND DO YOU HAVE ANY, WHAT WERE YOUR EXPERIENCES THERE? [8:47] MH: Well, I was one of the members of the Ranger Battalion—between the 1st and the 2nd Ranger Battalion—that was honored to be able to make the low-level combat jump in…Grenada. The primary mission there, Jeff, was a rescue of American medical students. There was appropriately 233 American medical students that were…at the time, the “intell” told us they was held hostage of some nature, but the bottom line is we felt that Americans were threatened, and anytime Americans are threatened we’re on call to come to their assistance—and we did. Initially, we [were] going to air land and escort them out. The situation become very hostile. Based on that hostility, we was unable to land the aircraft on that Point Salines runway, which was approximate 10,000 foot runway—a very large runway—that was constructed to hold large military transport aircraft. At the time, we thought that the politics involved included, you know, Cuba and the Soviet Union at the time in the early 80s, building that stepping, steppingstone to South America. And the main thing was our Americans were, we felt they were threatened—their lives were threatened—and I personally met one of them who is a friend of mine now—a doctor, a medical doctor—and he felt that he was never going to get out of there alive. [10:17] I met him after twenty years and we lived ten miles apart. I lived in Moundsville [West Virginia]; he lived in McMechen, West Virginia. We didn't even know each other. We was about the same age. My brother ran into him because he changed medical doctors, went for him, went to him for a physical and seen pictures on his wall hugging Ronald Reagan, and he was invited to a dinner, the students were invited to a dinner, to the White House back then, it was in 1983. And my brother Joe—who’s been a police officer for over forty years—asked him, he said “Jeep, what is that on your wall with [President] Ronald Reagan there?” He [the doctor] said, “Oh wow, I was a hostage in Grenada, and the Rangers come in and rescued us and some other Special Operations guys come in and rescued us. The Rangers was the actual…the ones who led us out of there and found out where we were. And Joe looked at him. He says, “Well, my brother was on that mission.” And “Jeep” is his nickname, and he says, “No kiddin.” He says, “Yeah” and he wanted to meet me, and so they set-up a meeting and we met and become friends ever since. 5 And he just went to a visit to Grenada last year—or, it was in 2003, it was like an anniversary—twenty-year anniversary—and brought back a couple of shirts and talked to me about it and shared his, what it looked like there, tourist attraction. [11:46] Economics there are good, are sound, people are happy, people are doing well in a democracy, so I think what we did was a good thing, not just humanely—getting our Americans out—but politically and all, so…but the, that was our primary mission was to go in there and escort them out, to become hostile. We couldn’t air-land and get them out. We ended an hour and twenty minutes, or sometime of that nature, putting parachutes on to jump in. [12:24] No reserve [parachutes]; we were told it was too low to jump in with reserves. Reserves are not going to do you any good—if your main doesn’t open, well, it’s your time to go anyway. As far as Rangers are concerned, their attitude is “whatever it takes to accomplish the mission.” So, a funny thing about that is, I was in HALO Jumpmaster in Yakima, Washington doing some HALO Jumpmaster Training with Special Forces, a cadre, and they called us up to go down there and I was used to making 17,000 to 25,000 foot high-altitude jumps and all a sudden now we’re jumping at low-level, at 500 feet, was the call I had at the time, with no parachute, so it was quite a different… a difference, the ground looks like, it was like you could step out of the aircraft and step on the ground. But nevertheless, we was told we were going in hot, and we did go in hot, there was combat activity going on. We jumped in, 1st Battalion jumped in, 2nd Battalion jumped in. There was a, you know, firefights going on (on the ground in several areas), pockets of resistance going on. I recall jumping in, when I jumped in and released my rucksack, the rucksack was so heavy we basically fell out of the aircraft. [13:42] It was nothing but ammunition and grenades and anti-tank weapons, laws, and claymores, and I think we might of had one meal or an extra canteen of water in there. Everything was ammunition: 60 ammunition, 7.62 ammunition, and two out of three ammunitions, for [inaudible] my grenade launcher, which I used to, had an M-16 dual purpose weapon anti grenade launcher. And we jumped in and I released my rucksack and I hit the ground so quick that my 14 foot, 10 inch hook pile taped type lowering line, which is escrow in the pack body hooked to your D ring on your harness, wasn’t even fully elongated, out of the pack body. [14:24] 6 That’s how fast we hit, of course I might of released a little late, but we got on the ground, we assembled, called in aviation support—fast movers, C-130s, AC-130s—and they begin to take out the gun positions located in the hills. They had ZSU 232s if I recall, and fours, quad 50 cal [i.e. caliber]-type machine guns—heavy caliber machine guns, they had antiaircraft guns located in the hills. They had trenches dug all around the runway with fresh AKs and ammunition all-around the runway, like they was prepared to defend the runway at all costs. I think we got the element of surprise when we jumped in, I think they expected us to come from the ocean and do a beach assault. And we didn’t. We come in low-level over the ocean. We hit the east side of the runway and shot up over the ocean to about 500 feet, I think it was. And under gunfire…we jumped, and we used the old T10 type parachutes so we… quick descent, get on the ground, high winds, it didn’t matter. [15:45] Later on, a couple years down the road when I was a Ranger Instructor…see I thought it was 500 feet, is what I was told, which is very low. And a couple years later I was a Ranger Instructor at Fort Benning, Georgia and I was the primary Jumpmaster for all the Ranger students, so it was my responsibility to go on to the aircraft and inspect the aircraft along with the pilots—the C-130 Air Force pilots. And I was talking to an Air Force pilot, he seen my Combat Patch and he says, “Ah, Grenada, huh?” I said, “Yes, sir.” He says, I says, “That was a good jump in there.” He says, “I flew that jump.” I says, “I appreciate your service” [inaudible] “and it was a good blast, wasn’t it?” I said, “It was a good 500-foot jump, wasn’t it?” He says, “It wasn’t 500 foot according to my altimeter; it was 400 foot. So I said, “Alright, that will work.” But nevertheless that was a light moment, and we went on to accomplish our mission. We had several missions. We lost several people out of the platoon I was in. Several people wounded. [16:51] Lieutenant Eskridge, who was my Platoon Leader, lost his leg on that mission. We had several people in the platoon that was wounded severely; several people in the company: Captain Kearny, was the commander at the time, good commander; Sergeant Klein (Gerald Klein), was the Platoon Sergeant, good Platoon Sergeant, but we took some casualties because we was the spearhead unit, for the most part, along with 1st Platoon. The Alpha Company itself was [a] spearhead unit. And so, we had several missions going on, stayed there three or, three or three and a half, four days. Several missions going on, all successfully accomplished, to include the attack on Calivigny Military Barracks to rescue the hostages, and a couple ‘search and destroy’ missions, cleaning up some of the areas in there, down around the airfield cause we kept taking sniper fire all day, so we did a couple movements to contacts. And we was the company that meet with the BTRs and destroyed the BTRs the initial day. So we was busy 7 for several days, but it was a good typical Ranger mission—in quickly, in unconventionally, low-level combat assault. Anyway to get in, we’ll get in, that’s typical Ranger attitude. Stayed there for just short period of time. Very busy, very productive. I taken out any position, any positions. And a very productive [mission] in getting out the hostages without any casualties on the hostages, and that was the key: that even though we’re committed and we know it's a dangerous job, the primary goal is the safety of the hostages and that occurred without any incidents or injuries and they all come home safe to their families, and that was something that the Rangers enjoyed doing, and they’ll do it anytime they’re called upon. [18:48] JM: AND I NOTICED THAT YOU MENTIONED YOU HAD LEADERSHIP, LEADERSHIP EXPERIENCE IN THE RANGERS THEMSELVES, AFTER… MH: Absolutely. I was a Team Leader during the actual Grenada operations. And, as a matter of fact, from there, I went to OCS [Officer Candidate School] later on, after being a Ranger Instructor. I spent six years in the 101st Airborne in the Gulf War, I was in the Gulf War as Scout Platoon Leader, 2nd of 502nd Infantry, 101st Airborne Division, so I was also in the Gulf War as a Scout Platoon Leader. Went on to get my graduate degree at Columbia University School of Public and International Affairs—and my PhD—become a professor at West Point [i.e. The United States Military Academy at West Point]. And after that, I thought that, for family reasons— and I wanted to put that PhD to work—I thought I’d go ahead and retire after 22 good years of service to our country and continue to serve our country in this manner, still working with young people [to] help set them up for success as they go out in the real world and take on that challenge of life and go for peace and American dreams, right here in America. JM: YEAH, AS A CALIFORNIA UNIVERSITY STUDENT, WE’RE LUCKY TO HAVE A PROFESSOR WITH YOUR BACKGROUND. MH: Well, thank you, Jeff, I appreciate that. Thank you for giving me opportunity to share some real word experience with you, sir. JM: MY PLEASURE, SIR. HM: Thank you. JM: THANK YOU. [20:20]