>> Kirsten Wiley: Good afternoon, and welcome. My... I'm here today to introduce and welcome Daniel Yergin, who...

advertisement

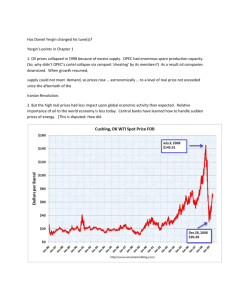

>> Kirsten Wiley: Good afternoon, and welcome. My name is Kirsten Wiley, and I'm here today to introduce and welcome Daniel Yergin, who is visiting us as part of the Microsoft Research visiting speaker series. Daniel is here today to discuss his book The Quest. Energy, Security, and the Remaking of the Modern World. It's actually on the New York Times best seller list right now, so we are very lucky to have him speaking at Microsoft. The world's appetite for energy is growing. The absolute numbers are staggering. Billions of people are becoming part of the global economy, and as they do, their incomes and their use of energy go up. Energy and its challenges. Where it comes from, who controls it, how it affects the planet will continue to be a defining issue for our future. Daniel Yergin is a highly respected authority on energy, international politics and economics. He received the Pulitzer for his book The Prize. He is the chairman of IHS Cambridge Energy Research Associates and serves as CNBC's global energy expert. Please join me in welcoming him to Microsoft. Thank you. [applause] >> Daniel Yergin: Thank you, everybody. I'm very pleased to be here and to be part of this event and to speak here under the auspices of the Microsoft Research visiting speakers session. And I also want to actually particularly acknowledge Curtis Wong because he -- a previous book I'd done and television series was called Commanding Heights, and it was kind of right at kind of a transitional point in terms of the web and so forth, and I continue to be very grateful to you for what you did in terms of driving to make sure that we had a web presence. And it's very interesting. We had a very highly rated TV series called Commanding Heights, but it didn't take very long before it turned out that more people watched it over the internet than over PBS, and so it was part of that transition, so I'm glad you're here today and to have the chance to meet you. So where I'd like to start is not with The Quest but the preceding energy book I wrote which was called The Prize. And a few days after Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, The Prize went to press with these final words: Ours is a century in which every facet of civilization has been transformed by the modern and mesmerizing alchemy of petroleum. Ours truly remains the age of oil. Well, that was two decades ago. That was the 20th century. We're now in the 21st Century. Oil remains the world's most important commodity, not only fueling modern society but in terms global economics and in terms of global politics. But so much has changed in the world of energy in so many different ways. And as I've found and was evident to me writing The Quest, first of all, the Soviet Union no longer exists. China, which was only, you know, a few words really in The Prize because at that time China was just a minor oil exporter, is now such a dominant factor in the world economy and world politics, and indeed, China is the only country that gets two chapters of its own in The Quest. So many other things happened. Climate change went from being an issue off to the side to being a major not only energy issue but economic and political issue. Oil, which was supposed to be $20 a barrel forever went to $147.27. The U.S. was going to import vast amounts of liquified natural gas. Instead, we have the Shell gas revolution which is changing the economics of the entire energy business. And then on top of all of that, just this year the dramatic and tragic accident at Fukushima in Japan in the course of the tsunami, and at the same time the Arab Spring, which, as it unfolds, has such implications for energy. So there was a lot that happened that made it very appropriate to try and make sense of the subject of energy. And that was the second thing. I really wanted to write not just about oil but write about the whole spectrum of energy. Natural gas, electric power, renewables, efficiency, climate change, and put it all together in a narrative and a story. And so all of those factors came together as I set out to write this new box called The Quest. Now, this story is populated by a host of very interesting characters. Some of them well known to everyone and some of them not well known and yet very influential. And I thought I'd just give you a flavor of them. Many of them, interestingly, are innovators, researchers, scientists in one form or another. And one of the -- Planet Money on NPR actually kind of talked about the role -- the important role that geeks play in this particular story. To just give you some examples, there's a professor at Cal Tech named Arie Haagen-Smit, and he was a great expert on kind of the chemistry of foods. He had figured out where the flavor of onions and garlic and wine came from, he was a man who achieved immortal status as identifying the active agent in marijuana, and he was fascinated and obsessed with trying to understand the flavors in pineapple, where that sweet flavor came from. And he was researching that one day in his lab at Cal Tech in Pasadena when he walked outside, I suspect to have a smoke, and instead of the clear, beautiful California weather which had helped to bring him to California, he felt in his lungs what he called that stinking cloud of smog. And he said, well -- at that time there was a huge debate as to what smog was and what caused it. He said I can figure this out. And he said he got it on the first nickel and he identified the cause of it. He became known as the father of smog, which irritated him a great deal because he said who is the mother of smog? But he then later, when the California Air Resources Board was set up, which has now become like almost the regulator of the world automobile industry, he was the first chairman, appointed by Ronald Reagan, and he went on from that to -- continued to do research on all of this, and you could kind of draw a line from when Arie Haagen-Smit walked out of his lab in 1948 to the appearance of the electric car on the road today. So that's one character in the book. Another is a man named Hader Alieth [phonetic]. Probably not many will know. A few will know his name. He was a KGB general. He rose to the top of the Soviet Union. He was in the polic bureau until he had a fight with Mikhail Gorbachev and was exiled back to his native Azerbaijan. It looked like things were over. The Soviet Union collapses, he emerges as no longer a Soviet man but a native son, the first native son, president of Azerbaijan, and more than anybody else is responsible for yoking Central Asia and the Caspian Sea back into the world economy where they had once been. Somebody else who's important is a young man -- you know, we know many people graduate from university today with very good degrees who are having trouble finding jobs, and this particular individual also had trouble finding a job. He in fact was reduced to tutoring sort of like Taplan [phonetic] style, and he even -- he actually offered free samples of tutoring trying to get business. His father wrote a letter to a chemistry professor and said my son grows unhappier day by day. He feels that his career has been permanently derailed. This young man was Albert Einstein. He then found a job in the patent office in Bern in Switzerland. It was not very taxing. It was a very slow summer, so over ten weeks one summer in 1905 he wrote five papers that changed the world. One of them was a paper on photoelectricity for which he won the Nobel Prize, and that became the basis of the solar industry that we have today. It took 50 years from that paper to get the first solar cells up on satellites in competition with the Soviets after Sputnik was launched, and here we are now 106 years later and solar is still kind of finding its way. So one of the things it tells you is long lead times in the energy business. I'll mention two or people I think who are interesting. One is -- I can assure you that this is the only book ever written on energy that will talk about the worst moment in Ronald Reagan's career as an actor. And that moment was when he couldn't get work as actor and was reduced to doing stand-up comedy fronting a singing group called the Continentals in Las Vegas. He came back to L.A., thought his career was finished, the phone rings, it's his agent on the phone, says, Ronnie, you know, I have a great new job for you, and he goes to work as the spokesman for General Electric. And there's a wonderful picture in the book of Reagan and his wife Nancy demonstrating this amazing, incredible new invention called a portable radio. And it's not that long ago. But the reason I talk about him in the book is because it's a way of talking about the great shift that happened in America when society after World War II, we got electrified. Nancy Reagan talked, in one of the ads for General Electric, about this amazing new electric servant, a vacuum cleaner. It was really -- I mean, all these things that we now take for granted. And what unfolded in the U.S. in the fifties and into the '60s is now what's unfolding in China and other emerging markets. We had 10 or 11 percent annual growth in electricity. Now they do, and their struggles with that is part of what is the current drama of world energy. I'll mention one last character who also has his picture in the book, a man named Jim Delson, who spent New Year's Eve 1981 atop a wind turbine in a blizzard in the Tehachapi Pass in California trying to get his turbine up by midnight because at midnight the tax credits expired, and so the economics depended very highly on this. He thought, there has to be a better way to do this, and so he goes off to Europe and discovers -- goes to Denmark and discovers that much sturdier wind turbines are made in Denmark, and they are made by companies that came out of this very sturdy, hearty Danish agricultural machinery industry. And he imports them, and for a time really the California wind industry in California in the 1980s was the epicenter of the world wind industry were these Danish wind turbines. And so part of what I tried to do in the book is not only look to the future, to the kind of question you said, but how we supply a world that will be 8 and a half or 9 billion people with energy, but also how do things happen. So I came to the conclusion that the modern wind industry, not the wind industry that goes back to Persia and Don Quixote and everything, but the modern wind industry really owes its existence to the marriage of the Danish agricultural machinery industry and California tax policy, and it's out of that that we have the modern wind industry. Well, these are some of the stories. And as I thought and as I was coming here -- and so many of you are involved in research -- realized that this is really a -- the role of the innovators of technological innovation, of people seeing different ways to do things, being able to act upon it is one of the main themes and stories that runs through this book. But there are three big questions that defined the story for me as I was working on it over these past five years. One is we have a $65 trillion world economy. After the downturn and growth resumes, it might be $130 trillion economy in 20 years, a couple decades. Where does the energy come for that? So that was of the first question. The second question was security, energy security, both in its classic sense, disruptions, concerns, for instance, about -- you know, we've had a Civil War in Libya that has disrupted supplies, we've had disruptions before in the Middle East, but also new kind of disruptions, and described by the Sony after an attack on their website as a bad new world of cyber vulnerability. And that is a question for the critical infrastructure of the energy industry. And then the third question is how do you put together the world's need for energy with the world's environmental objectives? And not a simple answer to that. So all of those together form the three questions that I kept knocking up against, I kept running into, as I was shaping my story. The big themes are -- one is geopolitics, which is just -- always has been and always seems to be part of the energy business, and this theme runs throughout the book. Geopolitics was a critical part of what people call the Caspian Derby, this bracing competition for who was going to have the control of oil and natural gas, the countries, after the break of the Soviet Union in the arena of the Caspian and Central Asia. Certainly the geopolitics of energy is fundamental in the relationship between the United States and China, and that relationship overall is so important to the future of the world and certainly to the future of the two countries and energy, and we can talk some more about that. One way or the other, Iran's nuclear program will have a major impact on world energy markets. Indeed, we can see in so many different ways now this sort of sense of rising tension and the tension between Iran and Saudi Arabia played out in Syria, played out in Iraq, played out in Bahrain, played out in Yemen, and add to that the recent plot to assassinate the Saudi Arabian ambassador at a restaurant in Washington, D.C., that the U.S. Government traces back to the Iranian government and hanging over all Iran's nuclear programs. So that whole set of geopolitical issues very much will have a major impact on what happens to energy. Indeed, also we've now passed beyond the Arab Spring, and now it's the challenging work of reforming societies, reforming economies, reforming legitimacy of government, but one thing we do know is that the consequences of the Arab Spring upended the strategic balance which has underpinned the semi-stability in the Middle East and, thus, the stability of energy supplies, and we're still in the early stages to see how the new balance develops, and that will have big implications for energy. Now, this geopolitics of energy is accentuated by something else: A new demand for energy, a demand for energy that's coming from what used to be called the developing world and today are called the emerging markets. One way to express it and the term I came up with to try and describe it is the globalization of energy demand. That, just like everything else, gets globalized. So has demand. And so kind of give you a sense of it, just show you how it's changing, if we want back to 2000, two-thirds of world oil demand was used in the developed countries: North America, Western Europe, Japan. Today it's 50/50 between the developed countries, developing emerging markets, and it's going to shift and the developing countries are going to be using more oil. And that's going to be accentuated by what we're going to have in our country, which is the term that I use in the book, peak demand. That is, we've reached a point where our oil demand is going to go down partly because everybody is going to be driving more efficient cars. By 2025 they're supposed to get 54 miles per gallon in new cars compared to 30, and also demographic changes have occurred as well. So all of these things mean our demand is actually going down while it's going up on the other direction. And, you know, when you look at the whole picture, one thing really stands out -you won't be surprised -- to use a real estate term, the build-out of China. You have 20 million people a year at least moving from countryside to city. They need housing, they need jobs, they need transportation, and all of that requires energy. And we can see it happening. China already uses more energy total than the United States. Much of that is coal, but an increasing part of it will be oil. And its growing demand for oil seems to be just locked in. It's going to continue to unfold. Let me give you just something that will make it very vividly clear. Let's again go back to the year 2000. In 2000 the United States -- in the United States 17 million new cars were sold. China, less than 2 million were sold. Now we go to 2010. China, 17 million cars, 11 million in the United States, and it's thought that the Chinese number could go up to 25 million or even more. And so all of that will be reflected in oil needs. Now, some see an inevitable competition for resources developing. I think it's very -- and you can see how that could happen, but I think it's very important that it actually not happen and in a there be the emphasize on the common interests between the United States and China as consumers interested in stable markets and, indeed, how interconnected the two countries are. Let me turn to another theme in the book, which is technology. And this really does get to the questions of innovation, the kind of issues that many of you are very involved with. And it is so striking that innovations that were dreams or theories or science experiments, to use a term that is used in Silicon Valley, in one decade a couple decades later just become part of the accepted normal part of the energy world, and we've seen it again and again. One place that is unfolding is in what's called shale gas, which is associated with that word that has now become well-known, fracking. It is only in about 2008 that it became evident that this was a major new resource, yet it had been 25 years in development, but it burst on the scene in 2008. And in some ways it might even be described as the biggest energy innovation of the last couple of decades, at least in terms its scale, in terms its impact. It's 30 percent of our natural gas production now. It's a number that is certainly going to continue to go up, and it's changing kind of the whole economics of the energy sphere. It's affecting the competitive position of everything from nuclear to wind. Now, it's very interesting on oil, kind of the familiar old energy resource, one has seen major innovations. And if you look at it in a hemispheric way, sort of quite striking innovations actually. There are three that are kind of changing almost the map of world oil. And they all are the result of breakthroughs, technological innovation, and they're basically all things that are post-21st Century in terms of their real impact. One is what's called the oil sands in Canada, which now produce as much oil as Libya produced -- exported before the Civil War began. Canada is by far now the largest source of U.S. oil imports and continuing to go up. The second is what the Brazilians called pre-salt, which is -- it took incredible computing power, and as the president of the state oil company says, amazing algorithms to solve the problem of identifying the oil that rested beneath this very thick band of salt. And Brazil is now on the road to being a powerhouse of world oil. By the end of this decade it could be producing twice as much as Venezuela, which has always been thought of as the big Latin American oil country. The third change is here, home-grown in the United States. It's what's called tide oil or shale oil. It's the application of the same technology that brought you shale gas to oil, and it has turned North Dakota into the fourth largest oil producing state in the country, and also -- I checked last night -- the state with the lowest unemployment rate in the country. And we're seeing that in other parts of the country too. And so this is also an area of substantial growth. And so you now have an oil boom back in the United States which people hadn't expected to see again. So that's technology at work there. Technology certain at work in terms of what I call in The Quest the rebirth of renewables, because you had the kind of -- the modern renewable industry began in the '70s, early '80s, and then it entered what people in the industry -- and some of you may know people or been part of it -- called the Valley of Death because it was -- the economics turned so adversely against it, the price of oil collapsed. No one seemed to care. And then around 2000 it began to change. It was not only for general environmental reasons, not only to for security reasons, but two other factors came into play. One is climate change and concern about climate change moving from a minor issue to a major issue, and then the growth that I was talking about before in terms the emerging markets and suddenly seeing there was going to be much more energy demand and seeing renewables as part of the solution to that. So you had people come into the energy business who were not there before, and in the chapter called The Science Experiment in The Quest I talk about how venture capital found its way into the energy business, and I quote one of the pioneers of venture capital in renewable and new energy, in fact, one of the funders of Tesla, the electric car, but he said in the '90s when he was making this investment, his friends thought he was committing career suicide, that it was all over. But he stuck with it, and in around 2004 Silicon Valley in general started to move into it and you sort of saw the kind of ecosystem of innovation at work in the renewable sector that you hadn't really seen before. So today I think if you look at the green industries, they're actually big businesses. Last year about a third of the installed capacity in dollar terms in electric power around the world was actually renewable energy. But it's interesting that they're big businesses, but they're also small when you compare them against the overall scale of the energy industry in its totality, and so the need for the renewables is to establish that they're competitive at scale, and I think that's the kind of game that's being played out right now. But you look at the wind business, a wind turbine today is a very different wind turbine than one in the 1980s and it might produce 100 times more electricity. So an enormous amount of progress has been made. And we see the progress in solar, and the name of the game there is just to drive down costs, drive down costs. We've also seen, of course, the migration of a lot of the manufacturing to China because of the advantages that they have in China in terms of low-cost manufacturing. So the view that I have in the book -- and I think you'll find it's really the story, again, where did solar come from, where did wind come from -- is to try and understand the dynamics and, therefore, kind of some sense of the pacing and change, although always with the sense that there are innovations that can come and surprise us and come from left field and, you know, although it's now sort of off the table, I would certainly say keep your eyes on what happens in terms biotech and energy. The other major theme is environmental considerations. And as you know, environmental considerations are challenging, the very notion of a future based on fossil fuels. Government policies are either looking for low carbon sources like natural gas or no carbon sources like wind and solar. And there, too, I got very interested in the question how did climate change go from being this very peripheral question to being such a dominating question. And I thought I was going to write just one chapter on it. I actually ended up writing six chapters on it because it was so interesting, and I found myself starting actually this story in the Alps in the 1770s and then in the 19th century finding scientists who -- you know, kind of one thing leads to another. Around the 1830s a famous scientist named Louis Agassiz kind of figured out that there had actually been something called an Ice Age that had preceded the current age, and people were fascinated with glaciers and started saying, well, if there had been an Ice Age, how do we know that another Ice Age isn't going to come back and that glaciers are not going to migrate down again and destroy civilization? And so a lot of the climate research that was the original climate research in the 19th century was about the fear of a return of glaciers. And one of the most famous scientists, Arrhenius, who identified how carbon could make the climate warmer, he was a Swede, he was depressed by those long, dark nights and the long, dark winters, and he actually thought it would be great if there was global warming because it would make Sweden a verdant paradise of crop growing. But it was really only in the 1950s and 1960s when, again, another key scientist, another key tenacious, obsessive individual named Keeling, who had done his Ph.D. at Cal Tech went to Scripps and began measuring carbon that you started to see the beginning of the consensus that now drives climate policy. Just a couple of other things on other environmental considerations. Up until March 10, one would have been talking about a nuclear renaissance because is seemed that everywhere around the world, you know, the accident at Chernobyl was long forgotten, Chancellor Merkel, the German chancellor, was pushing for Germany to reverse its policy and commit to a more important role for nuclear in its future. Then came that terrible accident at Fukushima and she led the change in Germany to say we're going to shut down our nuclear industry by 2022, and we see -- instead of a nuclear renaissance now, we see a nuclear patchwork, some countries going ahead -- China, Russia -- some countries highly undecided. Really, Japan is quite undecided itself about what it wants to do. In the United States, the Obama Administration has said that they want to continue to pursue nuclear because it's seen as the only large-scale carbon-free electricity, and there are a couple of projects that are going ahead. I would say that also local pollution -- although not so much in the developed countries -- in the developing countries is certainly driving energy innovation, and nowhere, of course, more than China where the air is so difficult and so painful to breathe, and it makes the smog of Los Angeles look mild by comparison. And so in China, a very strong drive for cleaner energy technologies. Now, I kind of bring the story of The Quest together around two subjects. One is what's called the fifth fuel sometimes, i.e., energy conservation or energy efficiency. I've always thought and I continue to think that it is actually the biggest potential near-term supply that we have, and in fact when people say, oh, we've made no progress in energy efficiency, that's actually not correct. As a country, we're twice as energy efficient today as we were in the 1970s and the early 1980s. And it might be a legitimate, reasonable national strategy to try and double it again. The problem is how do you make it vivid. And it was summarized for me by the European Union's energy commissioner when he was extolling the virtues of efficiency and trying to promote it but saying the problem about promoting against renewables that you just don't have any good photo opps for energy efficiency. Or what he said is actually there's no red ribbon to cut. And so I think that continues to be actually an obstacle, and yet the impact of it could be enormous. Now, I didn't think when I was going to -- when I started the book, that I would finish where I finished t but I finished it on the question of what kind of car you and everybody watching will be driving in 10 or 20 years. Is it indeed going to be an electric vehicle or is it going to be a highly efficient internal combustion engine that gets 60 or 70 miles to the gallon? Will it be hybrids? What's the mix going to be? The truth is I don't think we know. Certainly this arrival of the electric car is quite a major development. It takes -- it reconnects the beginning of the 20th Century with the beginning of the 21st Century because there was a race between the electric car and the gasoline-powered car at the beginning of the 20th century. Indeed, there's a wonderful picture in the book of a paint of Thomas Edison and Henry Ford having dinner together where Ford is telling Edison about his electric car -- not his electric car, his gasoline-powered car, and Edison says, you know, that's a great idea, and he says, That hydrocarbon that you want use, that's a really good fuel. But then a couple of years later, 180 degrees, changes his mind, doesn't like the pollution, says we can do it with an electric battery, spends a lot of time and money trying to get an electric car going, but Ford comes out with the Model T, $895 without the top, and lo and behold the race seems to be over. And here we are 2011 looking into 2012 and the race has begun again. There's a great set of two pictures The Quest. One is of a woman charging a car in 1910 and the other is the CEO of Nissan Renault charging a Leaf in 2010, and it's sort of -- the pictures, I put them together because they almost look like identical pictures and sort of saying this race has begun again, but it's still very early stages. And I think would be four or five years before we have clarity about what kind of scale is going to be achieved, and it will be something that will obviously have a very broad ranging significance. Now, in writing The Quest I recognized that there will be surprises, that there will be new developments. There are always these, quote, surprises that come along when everybody has a consensus and agrees where things are going and then it goes in a different direction. And they may be technology that may come out of labs, they may be politics, they maybe the result of economics. We don't know. By definition, they're surprises, although you can spend time working with scenarios and other things to try and see what they might be. But even as these surprises occur and changes occur, I hope that The Quest will provide a perspective on how our energy world has become what it is, what our energy world may look like in the future, and how to prepare for it. You know, you come to the end of writing a book and you've got to go back and write two key parts. One is the introduction to set it all out because you've learned a lot, your thinking has changed over the five years you've worked on it, and you have to write the conclusion to tie it together. Where do you want to leave people? Where do you want to leave readers? Where is your thought at the end of it? And I'd come across a quote by a man named Sadi Carnot. Engineers will know his name because of the Carnot cycle describing how a steam engine works. He laid it out in 1824 in a paper titled Reflections on the Motive Power of Fire. He wrote that the invention of heat engines using what he called combustibles was producing a great revolution for humanity. Now, Sadi Carnot is very interesting because he was not only a scientist and engineer, he was also a soldier. His father, in fact, had been minister of war for Napoleon, and he looked on the steam engine not only from an engineer's point of view but also from a soldier's point of view, from a geopolitics point of view, because he said that Britain had defeated France partly because of its mastery of energy technology, and he saw his mission was to teach the French about this technology to kind of right the geopolitical balance. And I thought that is really interesting because, you know, even at that stage the geopolitics was part of the energy picture. But as I looked The Quest and I looked at the people I'd written about and the developments I did and how these stories unfolded, I concluded and you may rightly conclude when you read The Quest that indeed a great revolution, that phrase of Carnot, fairly describes the entire process of innovation, of harnessing energy that began in the 18th Century. And this is clearly a revolution that will continue into the future. And indeed, I conclude that this -- and it's why I conclude that this is a quest, this particular quest, this quest around energy, is a quest that will never end and is a quest that never should end. Thank you. [applause] >> Daniel Yergin: Would you like a little discussion? >> Kirsten Wiley: Questions would be good. >> Daniel Yergin: Sure. >>: You mentioned increasing fuel economy standards for cars. Now, we've been there before. In the '70s they had fuel efficiency standards for cars so they invented the mini van. Then [inaudible] for minivans and somebody invented the SUV [inaudible] truck. Don't you think they'll probably invent some new name and get around it a third time? >> Daniel Yergin: Well, first of all you're quite right. And, actually, one of the fascinating things I had was going back saying where did the minivan come from, and it was kind of an odd idea that Chrysler had. And in the early 1990s, on the basis of its progress with the minivan, people called Chrysler the most successful automobile company in the world. And indeed, I talked to the former CEO of General Motors and he talked about how General Motors was trying to catch up with minivans and trying to meeting the demand for SUVs. Partly, Detroit went in that direction because once gasoline prices went down, then consumers sort of -- Detroit had to make these efficient cars, but consumers weren't buying them, and, thus -- and, of course, the reason trucks, as they were called, minivans, SUVs had different fuel efficiency standards because, you know, no one drove them in the '70s unless you had a work reason for driving them. And then the invention of the -- the appearance of the soccer mom and it became a whole, you know -- and at one point half the new vehicles being sold were these kind of cars and America's love affair with the automobile turned into a mad passion for the SUV. But it was clearly connected to low gasoline prices. The highest sales were at the end of the 1990s when, in inflation adjusted terms, gasoline was cheaper than it had actually ever been. So I think that -- I think people are onto it now, and I think that the fuel efficiency standards are being rewritten -- have been written in such a way that they apply to those as well. So I think the whole fleet is going to move in that direction, and I think I see Detroit, the ethos has changed, and you can see the cars -- the focus on efficiency. Now, if everybody changes their mind and don't care about it again, then you could kind of have another crunch. But it seems to me it's more widely locked into kind of, as somebody says in The Quest, the DNA of thinking about it. But that is -- Detroit's fear is the volatility on the part of the consumer. >>: How do you see the end game for oil playing out? In what time frame? >> Daniel Yergin: By the end game ->>: The end game as in like when we stop burning oil to transport ourselves around or make energy. >> Daniel Yergin: Well, kind of think out to 2030. Once you get beyond that it gets awfully hazy. I think that one picture would be that we reach a kind of plateau sometime around the middle of the century, and then we get -- we get in the U.S. peak demand and decline, we start to get it on a global basis. If the electric car, other forms of transportation, come on more strongly and can economically displace the automobile, that could happen more quickly. Then you have the problem about how you generate your electricity. So I see it as a sort of -- not a sharp change but a long goodbye. >>: What about for aviation? Is there anything on the horizon there? >> Daniel Yergin: Well, the Defense Department is trying to do create -- when you talk about oil, you're putting biofuels in a different category? >>: Yes. >> Daniel Yergin: Right. Certainly the Defense Department is promoting and trying to develop a drop in biofuels that would replace jet fuel. And so that's an area in which a fair amount of research is going on. The Secretary of the Navy talks about a great green fleet and that he wants it to be half of the Navy's energy coming from non-oil by 2020, which is a very ambitious goal. So kind of one of the drivers there is the Defense Department. And also, of course, they're just aware of these convoys whereby people get attacked and so forth, and many of them are bringing oil. So are there other ways -- kind of other ways to use energy. So I think, as so often happens, that actually defense military may be a major solvers innovation. I have in The Quest the story about how Churchill converted the British Navy, Royal Navy, from coal to oil specifically to gain speed and flexibility against the German fleet. And so I think that will be a source of innovation. >>: Do you discuss hydropower? >> Daniel Yergin: I don't discuss it much. I mean, obviously it's interesting. If you look, last year about 8 percent of U.S. energy was renewables. If you go back to 1985, about 8 percent was renewables, but it was a much larger segment of hydropower. I think it's quite difficult to build large dams. And so it's kind of [inaudible], you know, but it doesn't seem to be a growth area. I don't know if you had a specific thought that you had ->>: I was just wondering, because it's one of these technologies that's been around for a long time, but it's sort of not really considered renewable the same way solar and wind are. >> Daniel Yergin: Yeah, it would be very difficult to build any large dam in the United States, and some would like to see some of the dams taken down. So, yes, it's not -- there was a period of great interest in small hydro, but even that involves damming rivers and so forth, and so there's controversy about it. >>: For emerging markets, what are your thoughts on India's energy needs, and do you see [inaudible]? >> Daniel Yergin: It's interesting. One of the innovators that I profile is an Indian wind tycoon, and he started the -- going into the wind business basically because of the shortage of electricity. Factories were shut down for five hours a day because they didn't have power, and here he could offer a solution to people. So I think -- so a fair amount of interest in renewables in Indian entrepreneurship around it, and India does have these formidable Indian institutes of technology which really turn out first class talent. So I don't see the same kind of focused direction from the top that you see in China, but clearly a lot of entrepreneurial energy going in that, and Suzlon is one of the major wind companies world, and its foundations are in India. >>: Whatever became of the hydrogen economy? >> Daniel Yergin: I think you had a speaker here -- didn't you? Did you have Jeremy Rifkin -- no? It's kind of one of the those things that's always out there, and -- you know, I remember at one point we were going to have a conference we do every year in Houston, we were going to have the Secretary of Energy speak and he was going to speak about hydrogen, and we just said, you know, you might want to use the word long term. So it always seems to be out there. >>: You mentioned your pet fuel being efficiency. We're already see in the U.S. sort of some distortions or some real insidious utility companies with their tarriff setting because their demand is coming down and they're focusing more on [inaudible] than they are on renews and use, and along with that you're seeing some consumer push-back or rate payer -- rate setting interventions from people who don't like the fact that so much more of their [inaudible] is just going to be to do infrastructure recovery rather than the variable costs recovery. It's almost a distortion like what happened in the wire line phone companies where that business just crumbled pretty quickly >> Daniel Yergin: I think it is a challenge for utilities. How do you turn energy efficiency, define it as an energy source, and then make -- you know, make money from it. How do you design rates to do that. There was a lot of enthusiasm about smart grid even until fairly recently, but then it turned out that one of the ways that you would -- you know, you would promote greater efficiency was with variable rates, time of day, and it turns out a lot of people don't like that. They want to have predictable rates. And certainly in the west there's been some real rebellion against it. So you don't see quite the excitement. But the basic thing is it should create a situation where it's neutral for utilities whether investing in new generation or whether they're investing in efficiency because you get the same impact. And I think in general utilities would prefer not to build new capacity because it's expensive and so forth. One thing we do see is that, you know, oil demand may be going down, but at least in our view, electricity demand continues to go up, and one of the reasons is, as you all know, servers and just the proliferation of gadgets. And so we talk -- I talk in The Quest about gadget watts, and those need to be supplied. Because if you go back to the Ronald Reagan day, the amount of electricity use in the home was pretty limited to just a few different things, and today just think of all the things that you have to keep charged all the time. >>: So I wonder -- by the way, I drove to this speech in a Nissan Leaf. >> Daniel Yergin: So tell us about it. >>: It's fantastic. And actually one of my questions when you're talking to the auto executives, in the PC industry there's something that we call the Osborne effect where an Osborne computer said, hey, just wait, we're going to have this fantastic computer, and they went out of business because everyone waited for that next fantastic computer. And so I'm wondering if any of the auto executives have an answer for how do you keep talking about these fantastic cars, the electric cars that are coming out, and not put people in a position to say, well, that would be great, so maybe I should just put off buying a car. >> Daniel Yergin: Right. By the way, do the questions get picked up for the ->> Kirsten Wiley: Yes. >> Daniel Yergin: Oh, they do? >> Kirsten Wiley: Yes. >> Daniel Yergin: Right. Good. The -- I have to think about the Osborne effect. And so your question is that rather than waiting for the perfect car -- can you just ask the question again? >>: Well, yeah. I mean, if I were to expand it, like I have some people respond as I talk about how fast and peppy this car is and how many miles it gets and how cheap it is to refuel it with electricity, recharge it. One of the things I've had people say is, well, I'll wait until they have a longer range or I'll wait until a bigger vehicle or -- you know, there are lots of different features that are important to people. And so you have two sides, which is one side is getting people onto buying something that they've never bought and they're not familiar with, and the other is discouraging people from buying a product that you currently make, which is, of course, a gas-powered car. So I know there's kind of a delicate balance between those two and where you put your marketing dollars, and I wondered if they had ->> Daniel Yergin: Well, I think all the companies -- I mean, not only -- what's interesting is you are getting a positive consumer response. I spoke the other day at, of all places, an automobile museum in Los Angeles, and there was a guy there who's actually in the business of refurbishing Corvettes, and he couldn't stop raving about his Chevy Volt and about how much he loved it. And I thought it's culturally very interesting. So I think you are getting early adapters, early users, and that feedback -- I mean, we're now in that stage that we'll feed back. I find among the automobile makers there's a kind of range of views. I talked to Carlos Goshn from Nissan Renault and he is -- you know, he's gung ho and feels this is the future and push ahead on it. I will Bill Ford in the book, though, who says we don't really know what the car in 10 years is going to be, so we have to play on all fronts. And the same with Daimler. Because I think the general thing you hear is that the cost of the battery has to come down. You still have a car whose price is -- you're not really reflected in it, and there are a lot of -- you've got a $7500 tax credit, et cetera. So that's why I say we're in this kind of period, but I think the feedback and people, you know -- this person, that person hearing what you're going to say, they're going to be -- feel more comfortable thinking about it too. And so we'll kind of see what the demand is. I mean, hybrids have been out now for 10 years and they're still a relatively small part of the mix. I know some automobile makers actually think the hybrid is really, truly the way to go. So I think it's still a testing period, but I think everybody in the room is actually very interested in your experience, which it sounds like you would describe it as positive. >>: Yeah. Very positive. >> Daniel Yergin: What made you decide to buy it? >>: I'm an experimenter. I'm sure everyone in this room, we're all gadget crazy, so, I mean, it's very much a technology gadget if you think about it. >>: Would you have bought it without the tax credit? >>: Absolutely. >>: Do you think anybody else would have [laughter]? >>: Well, it's relatively affordable. I mean, it's not like the hydrogen cars that are out there that are a million dollars ->> Daniel Yergin: Or even a Tesla Roadster. Those are a good deal more expensive. Well, I think this is really interesting. I think these are the data points that the early adapters, later adapters -- and it will partly depend upon the enthusiasm. I think that, by the way, you don't actually -- I mean, the psychology of global energy markets, even if there are not a lot of electric cars, if there are enough of them, people are satisfied with them, that will start to change psychology because what it will say is you'll have a system that's not primarily almost totally dependent upon oil. There are alternatives. Then you'll get into the question of how the electricity is produced and all of those other questions. But thank you for the comment. I think there and then we'll come to you. >>: So if we decide that we need to walk away from nuclear energy altogether, how far away are we from being able to replace all of our fossil fuel energy needs with renewable energy. My question is can we really, as a global economy, say nuclear energy is too dangerous? >> Daniel Yergin: Well, it's 20 percent of our electricity. It's about 30 percent of Japanese electricity. I think it's obviously almost 80 percent of French electricity, 77 percent. So I think it is embedded in the mix. By the way, one of the other great characters is a man who's probably more responsible for nuclear energy than anybody else in the book, Admiral Hyman Rickover. A few of you will know his name. Many won't. But he was the father of the nuclear navy and the father of nuclear power, and you do look back on it and it was actually done rather remarkably quickly actually, far quicker than people thought would be possible. There's some interest in small nuclear modular plants as a kind of alternative where they would be built almost like in a factory and then rather than have the kind of construction that you do now -- at our last meeting -- I'm on the Secretary of Energy advisory board -- that was a topic of discussion. But we will face, in a way, your question because nuclear plants when they're first established have a 40-year lifetime and then pretty clearly get a 20-year extension. But they get heavily upgraded in the course of that. I mean, so many things get changed. The next 20 years, then there starts to be a question, at least I hear people saying, about just will the economics work to retrofit them again so that they can go 80 years. So I think in a way what you're raising is a question that will start to come on the agenda in the next five or seven years, and I think renewables clearly are going to grow to a very important role, but there's a gap that would have to be filled. Right here. >>: Related to that, given the challenges of the economics behind solar and wind, are there sustainable policies that governments could implement to help us at least diversify our energy portfolio a little bit more? I think everyone's aware of some of the policies that have risen and been squashed, but do you have some thoughts about what policies might be more effective? >> Daniel Yergin: I think that -- I mean, it was Germany really that's responsible for the rebirth of the renewable industry starting in the 1990s. And there they did it with what are called feed-in tariffs which kind of blend the high cost of renewables so they're blended to the overall electric price and people don't really see it and so it gets the industry going. We do two things in this country. One is the tax incentives which exist, and we have different -- the tax incentives that Jim Delson [phonetic] was trying to get on that Tehachapi Ridge in 1981 were based upon just the capacity, but now it's based upon how much electricity you produce. And then the other thing that I think is very significant is the portfolio standards that the states have, and that is a huge driver. I mean, Jerry Brown in California just signed a bill a couple of months ago saying that California will get one-third of its electricity from renewable by 2020. A very ambitious goal, particularly in a state with 12 percent unemployment. But, nevertheless, directionally it tells you where it's going to go. So I think those are the kind of -- affect the decisions that get made and probably what's really actually accelerated wind and solar and the idea is that the more you have, the bring down the costs. So I think those are the kind of policies. I think in this era of fiscal austerity we're not going to see a lot of new policies, we'll see retrenchment, and one thing I worry about is what happens to the basic research and development budgets and just maintaining their integrity through this what might be a very stringent period. We'll come around. >>: As the costs for different co-gen technologies out there, you know, ma and pa can go buy solar panels, put them on their roof and there's the fuel, so as that becomes more cost effective, when do you think that that type of energy source will become a significant part of the grid? Or will it ever? >> Daniel Yergin: Well, I think wind is kind of -- in the last few years before the downturn a significant part of the new capacity being put in was wind, and so wind is much larger than solar. I think solar has clearly grown a lot. It's a global business, but just look at the percentages. It's still very small. And, still, it's a question of, you know, of getting the costs down where these compete without subsidies and incentives. But that's the name of the game, and I see it just so much on solar. It's all finding new ways to bring down the cost. Wind is a business that's already kind of dominated by the Siemens and the General Electrics and the [inaudible], so it's already -- and, of course, there too you see the Chinese companies, they're clearly global leaders in solar now in production. What their role will be in the wind business is something on the mind of everybody in the wind business. >>: Do you see telepresence playing a big role in the efficiency fuel? >> Daniel Yergin: So that we don't have to travel? >>: Right. >> Daniel Yergin: Probably. Yeah. Yeah, I mean, that's something you all work on here and -- [laughter]. We had Steve Palmer at our conference in March, and he certainly was demonstrating and talking about it. >>: Do you know of any data that exists on its effect today? >> Daniel Yergin: I don't. I don't. Somebody probably in the room does. Does anybody here have a handle on that? >>: Like the potential impact of telepresence on producing travel? >>: Yeah. Like how many people are watching this and ->>: [inaudible]. >>: He's not going to share it with you, but -- [laughter]. >> Kirsten Wiley: That's funny. >> Daniel Yergin: Okay. I think -- you. >>: So can you share your unvarnished thoughts on carbon capture and storage? >> Daniel Yergin: Yes. Carbon capture and storage, the notion is that you capture the carbon one way or the other out of a power plant, compress it, transport it and bury it somewhere. And, you know, you do the numbers and you come to the conclusion that it would be as though you were creating a whole new energy industry that works in reverse, that goes backwards. And the system we had, what is it, 150 years old or however you want to say, so -- and at least at this point you don't have any really significant demonstration projects of it, and the cost of it is -- people send it [inaudible] 75 percent or 100 percent of costs. So there are some people -- clearly, it's one of those things people are working on and committed to and trying to make it work, and at least it may be part of the solution. But it's hard to imagine it on a huge scale. And then the question is once you bury the CO2, who owns it? Who's responsible for it? What happens if there's a leak? I'm on this commission that we're reporting to President Obama on shale gas, and we know the controversy around that. So I think there's this the whole -- the whole legal side of it is still unclear. So I guess I would say it's kind of part of the mix, and people will do it, and some projects may be built that way, but we're far, far, far from seeing it as something of large scale. >>: Sounds like it's as far off as [inaudible] to some extent. >> Daniel Yergin: Well, I don't know in chronology where to put it, but, you know, as John Deutsch of MIT says, you need a couple of significant demonstration projects first, and we're not there yet. And so that's the kind of first gating item that you have to get through. Well, thank you. It's great to be here. I enjoyed it. Thank you very much, and everybody who's viewing this, and if you offer, I'll take you up on a ride in your Leaf to the airport. So thank you very much [laughter], and I'm glad to be here with you all. [applause]