22140 >> Kirsten Wiley: So good afternoon and welcome. ... and I'm here today to introduce and welcome Evgeny Morozov...

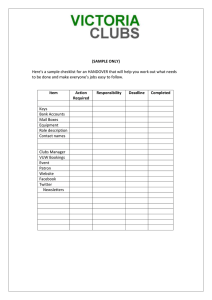

advertisement

22140 >> Kirsten Wiley: So good afternoon and welcome. My name is Kirsten Wiley, and I'm here today to introduce and welcome Evgeny Morozov who is visiting us as part of the Microsoft Research Visiting Speakers Series. Evgeny is here today is discuss his book, the Net Delusion, The Dark Side of Internet Freedom. Easier access to information and communication tools are not just utilized by helpful revolutionaries. Authoritarian regimes are using the Internet to suppress free speech, hone surveillance techniques and disseminate cutting-edge propaganda. The Web is as likely to distract as it is to empower. And both dictators and dissidents alike can exploit its novel features. Evgeny Morozov is the contributing editor to Foreign Policy and a regular contributor to Newsweek, The Economist and many other publications. He was the 2009/2010 Yahoo! Fellow at the Institute for the Study of Diplomacy at Georgetown University, and a 2008/2009 Open Society fellow with the Open Society Institute. Please join me in welcoming him to Microsoft. Thank you. [applause] >> Evgeny Morozov: Thanks for this introduction. And as you can probably immediately grasp from my accent, I come from Western Europe. I was born and raised in Belarus, and that probably explains why I've been so fascinated with not just the subject of how the Internet can promote democracy, but also the subject of democracy promotion in general. And this is what actually initially drew me to this subject. As you may know, Belarus is one of those places where you probably do not want to be a pro-democracy activist because it's not politically safe. A few years ago, Condoleezza Rice described it as the last outpost of tyranny in Europe, and I think it was probably an understatement on her part. So I've always been fascinated with finding new ways in which to open up and democratize the country, and I would say in 2004, 2005 when there was a lot of talk about the power of the media in the U.S. following the presidential election here and following the ways in which the [inaudible] campaign made use of new media, I began thinking about ways in which the same technologies and tools could be used in more closed societies. And this is how I began experimenting with all the blogs and social networks and wikis, could actually play in a country like Belarus. So I ended up working for an NGO, it was not based in Belarus but it was based in Prague over the former Soviet block and other countries in the region ended up working in 29 plus countries. And I eventually became their director of new media, and I was sort of an evangelist, if you will, for new media. So I was traveling around places like Kazakhstan or [inaudible] or Belarus, and meeting with activists and bloggers and journalists who were mostly in the opposition, of course, trying to train them in what they need to know about new media activism, how they can actually use it to their benefit, and a lot of our work was funded by [inaudible] foundations, mostly Americans ones, things like national democracy and by the European Commission. So there was a lot of excitement about the power of new media to bring political change to countries like Kazakhstan or Belarus back in 2005, 2006. So this questions for Internet freedom, which Hillary Clinton began a year ago, it's not new. The U.S. government and many of the foundations in this space have actually been funding a lot of bloggers and a lot of activists to take advantage of new media since I would guest the year 2000 if not earlier. It may not have been called support for blog, it was called something else. But a lot of these activities were present. In the three years that I've been doing that work, I became increasingly skeptical about the power of technology and the power of new media to change the situation politically in many of those countries. We do not operate in the middle west, but we operated, as I've said, in places like [inaudible] and places like Moldova and Belarus, and it was than quite a ranging list of experience for myself. And I noticed several things. I noticed that the assumptions that were made by most policy -- western policymakers who were helping out work -- were very naive and banal. They didn't have a very strong theory of change in terms of how blogs and social networks would live through democratization but they also had very little awareness of how their own support for such activities could actually harm or threaten the dissidents or bloggers. Few of them had the awareness of providing funds to bloggers in Belarus or a country like Kazakhstan may actually endanger their lives because that money comes from the United States. Nor did they consider the ways in which providing big grants to NGOs like ours, funding bloggers independently would actually create some culture of dependency in those countries. And would actually push away the people who would otherwise be innovating and building their own blogs and social networking sites and doing it because they wanted to do it, doing it because they hoped to get some money. It would basically put them on the U.S. government's payroll or the payroll of the foundations. And they would operate in a completely different innovation cycle, where they would wait for another 12 months until they get another grant, or they would fail deliberately to get another grant to fix whatever they have done wrong in the previous one. So I didn't like the dynamics in which that market was developing, and in which that environment was developing but I also noticed that authoritarian governments themselves were actually becoming much more sophisticated than we initially thought they would be. Our initial theory back in 2005-2006 was that all they would do would be Internet filtering. They would just be blocking access to specific websites they don't like or they'd just be blocking access to certain keywords. And we saw that's the cost we need to pay. And back then we knew there were tools that would allow to circumvent censorship, so not particularly worried about the authoritarian government sensoring this space and trying to at least control the conversation. But I began noticing that they were increasingly more sophisticated and the strategies they used were much more advanced. So Russia country I know pretty well. To me was a very interesting example. There was actually very little Internet censorship and Internet filtering in the country. They don't block access to almost any websites except for child pornography and a few extremist websites from the separatists and the caucuses. But everything else, all the political content, stays online. They don't really practice Internet filtering. But I would argue there's still many ways in which a government like Russia actually exerts a lot of pressure in the blogosphere and the new media environment in general. Some of it happens by establishing control over the new media platforms. So as you probably know, back in 2006, Anglagard who was very close to Kremlin actually established full control over Live Journal, which is the most popular and most influential blogging platform in Russia. Since then it became a full Russian company run by people who are still -- now has actually been resold to Anglagard who is even friendlier to the Kremlin. And some people think it has an impact on how it's abuse works and how to identify content and whatnot. Again, it shows -- at least to me it shows a little more sophistication on behalf of the government. But we are all becoming to discover new ways of surveillance, for example. In Belarus, the country where I come from, the security service, which is still called KGB, is actually in the habit of going through the social networking profiles of activists, which are, of course, publicly accessible, with the sole purpose of identifying how they might be connected to each other, but also identifying some of the new people who may be activist but who may not yet been on KGB's radar. So there are instances in which I also document in the book of them actually discovering new targets by just going through the social networking profiles of people they already know. So and that, of course, presents a dilemma, because in some way the activists who are on social networking sites, many of them are aware of the problems. And many of them are aware of the vulnerabilities. But because they need to be able to present their messages and to bring attention to their causes, that's the sacrifice and cost that they have to pay. So, of course, we need to continue educating many of them about the particulars of the data, policies of many companies, how they release data to third parties and so forth. But again that's the trade-off I think that many of them have made, unfortunately. But we're also beginning to see other forms of intimidation. Cyber attacks, specifically denial of service attacks, suddenly became very prominent and very influential, as a means of not only silencing independent publishers and bloggers and journalists, but also just exerting psychological pressure. In the book, I document very interesting example that I found in Saudi Arabia, where there was an online forum dedicated to philosophy. And philosophy is actually banned in Saudi Arabia as an academic subject. So the Internet was pretty much the only space where those people could come together and talk about it. And the moment that forum began gaining in popularity, it immediately became a target of denial of service attacks. And it was run on pure enthusiasm of several Saudis who were not wealthy, they were from the middle class, they just put their own money into the project. And at some point, as the cyber attacks became really severe, they basically got a call from their hosting company and were told that the company doesn't want to host them anymore. The company was in Canada. They then moved to another one. And the cyber attacks followed them there. And at some point their choice was to either seek protection from companies that offer basically protection from DDRS attacks and pay seven, $8,000 a month, or to sustain the attacks and risk the chance that their website may be down one week out of four. And they couldn't afford to pay. So in the end a lot of the users left, and they didn't return. So we see denial of service attacks basically as a means of undermining and weakening online communities. And that attack is very popular now also. So they also empirically used as I've noticed during particular political events. So often, for example, in Belarus we had the election in 2010. And what happened was several that things happened, first of all. There were DDOS attacks. So the websites of the independent media were not accessible because again they were attacked. But also very interestingly, someone managed to -- and I didn't know all the technical details how that happened, but someone managed to replace the front pages of the main opposition on newspapers, with the same basically pages, but that were at least a day old. So anyone who basically wanted to know about the protests and read the news could only access the news that was one day old. So people couldn't actually get the updates because there was an orchestrated campaign to basically, first of all, prevent news from being published but also to make it seem as if everything was normal. So in some sense it was a concentrated effort to make it seem as if those websites just basically didn't update themselves for a day. So, again, that was something that I myself was not even anticipating, as a tactic. So having seen all of that in the three years that I was doing this work, as director of new media and this NGO, I just decided to step back a little bit from that work and try to think through some of the -- first of all, intellectual assumptions, if you will, of how back in the '90s many of us thought that the Internet would transform the world and how to transform it through authoritarian states and how we in the west and those who care about democracy and who want to make sure that countries like Belarus or China become more democratic how we can take advantage of the Internet. And the problem that became to me very prominent and obvious in 2009 was that a lot of the infrastructure, electronic infrastructure and digital infrastructure that's being used for online activists in many of those authoritarian states, is built not only by private companies but by American companies of which you are one. So you have of course Google and Facebook and Twitter who own all the sites that are used for organizing the protests and used for discussing things that the governments basically do not like. And that's a new problem -- that's not a new problem, we knew about that a long time ago. What I think became really obvious in 2009 was that it would be very easy to link the foreign policy agenda of the United States with its technological dominance, when it comes to [inaudible] and other services. And many governments made that connection. And that became, I think, really, obvious during the protests in Iran in 2009. So if you followed those events closely, I mean, we can debate forever about the role that the Internet has played there and the role that Twitter played there. I spent an entire first chapter more or less trying to make sense of what happened in Iran. And the only tangible evidence I've seen came from Aljazeera, who actually they did some research and they did some fact checking immediately after the protests in Iran and they could only identify 60 active Twitter users in the country during the protests. Which is, of course, not what we heard with the many pundits proclaiming that Twitter was widely used as a tool for organizing the resistance and organizing the protests. Now the fact that there were only 60 of them doesn't mean that Twitter wasn't important. Of course it helped to get the news out and it helped to inform many people in the west about what was happening and it was used by the [inaudible] to communicate to each other and also to mobilize other people who may not have been following the events. All of that is true. But the truth is that it was not used very vitally, or at least widely as most of us believed for the actual organization of the protest. However, what happened was that I think of the Iranian government at this point believed that Twitter was one of the fundamental tools and platforms for organizing those protests. In part, because they tend to be far more paranoid than anyone in the west, because they have something to lose. Right? So they are the ones who are reading the same headlines and the same articles and who are more or less prone to exaggeration, if only by virtue of their paranoia, about their own survival. So what happened afterwards in Iran was very interesting. And I need to provide an additional detail here. Some of you may have noticed that the state department actually reached out to Twitter during the protests, and they asked them to delay their planned maintenance of the site. Twitter, for some reason, wanted to have maintenance during exactly the same days that was at the very beginning of the protests when Iran had elections. So an official from the state department reached out to Twitter, and asked them not to do it because it would interfere with the protests. And that news eventually leaked out to the New York Times and was front page news of how the Obama Administration is pushing its new media potential everywhere, foreign policy included, so it was basically used to highlight how new media savvy the Obama Administration is. But the Iranian officials interpreted that very differently. They, of course, again by virtue of their paranoia, assumed that the state department was actually pulling strings somehow and was actually responsible for the turnout of all those young people in Iran in the streets of Tehran, who actually are asking for the overthrow of the government. That in itself, I think, merged two up until then diverse narratives. One was about regime change. And regime change that is more or less facilitated from abroad, one which Iran already has a lot of experience. That was one area. Then it was another area about the use of technology and the way in which technology can be used for mobilization. And those two narratives merged in that way. So as far as the Iranian officials were concerned -- and I actually track how they reacted to it and Iranian official media and editorials on that subject immediately after the protest, as far as the Iranian officials and Iranian public was concerned, what happened was that there are those people sitting in Washington and the state department who are basically trying to take advantage of the fact that so many of the servers are American, and they're trying by some mysterious means and ways to basically use them for facilitating online -- well, off-line protests, and facilitating riots, uprisings and whatnot. And that was the narrative that actually was then repaired not just in Iranian media but also in the Russian media, in the Chinese media, even between papers in Moldova, and more or less was the same sort of take-away from what happened. And I think that sets a very dangerous precedent for America, but also for the Internet, because that triggered a whole different country dynamic in Iran itself, was the government immediately setting up several units of what they call Cyber Polic which began to monitor the Internet very closely. They set up their own social network to lure young people away from Facebook in which they are now pouring a lot of paid resources. They're trying to launch, if they haven't already, their own search engine to lessen their dependence on Google. You may have seen that they've banned access to Gmail in February of 2010. They have been sending text messages to the public threatening them with retaliation if they start cooperating with or even responding to any calls on Facebook. There was one of the Ayatollahs released a statement saying that participating in cyber war is okay as long as you're fighting the western enemies. But the biggest take-away for me, at least, was that the Iranian government responded the way they did, not so much to distract imposed by the Internet but to the threat of regime change. Engineered from abroad posed on the Internet. That concluded a very different response from them. That is the response that at least I'm beginning to observe elsewhere, where governments like Russia, the Russian government or the Chinese government, or even the Turkish government, want to lessen their dependence on American companies, whether it's Facebook. Whether it's Google, whether it's Twitter, perhaps Microsoft as well. So the question that we need to ponder, I think, is whether explicitly embracing a concept like Internet theorem as, for example, Hillary Clinton did with her first page on this subject a year ago, in which she did again just a month ago, whether doing it explicitly would actually somehow make it harder for America to promote the Internet theorem, and would it actually result in an Internet that would not be conducive to the promotion of democracy, feeling of extraction, human rights. The problem that at least I begin to identify is that when these regimes start replacing American companies with their own local clones, whether it's a social network in Iran or a social network in Russia where it's a whole social networks in China, as you know, video sharing sites, those tend to have far more restrictive practices and norms when it comes to freedom of expression. They are much eager to censor what American sites and services would not sensor, because, again, they would be under pressure from domestic media here and any acts when someone from the Chinese communist party places a call to Google or Microsoft and asks them to remove something from their site because they don't like it. While figuring out, while it doesn't trigger it out when it happens to local Russian or Chinese company. It actually happens all the time. [inaudible] McKinnon who studies the Chinese Internet, some of you may know, a very interesting experiment about a year ago. She basically created I think about 40 different blogs on 40 different blogging platforms in China. And she posted the same controversial antigovernment content on them, ranging from mentions of human rights to Dhali Lama to Tienemen, to sex. It was an academic study, but it was wide range of content that she published, and she just wanted to see how long it will take for the Chinese companies to remove that stuff. And, of course, all of them differed. Some of them removed it within hours and removed just a quarter of all materials she posted. Some of them removed more than a half. They all differ in terms of how they sensor and how much they sensor. But that happens because the government never specifies what exactly it is that needs to be censored. So the companies are left guessing because they don't want to run into any problems with the government. But the reality of that overall probably, they sensor far more than would be the case with foreign services. To me, a very interesting example here is Vietnam, which as some of you may know actually banned Facebook about a year and a half ago. But they not only banned Facebook, they also started their own state owned social networking site called Go on Line. Not a very creative title. They allocated four or 500 staffers who would basically trying to make it into a competing and competitive product. And of course it's very easy to compete when Facebook itself is blocked. It actually looks very much like Facebook. And the implications here, of course, are you just have to think about what the implications might be. It may be that the government would be spying on the private communication exchanged by the dissidents, with any other users. It may be that they will be shutting down that website during particular political events when they have protests, when they have elections, to make it unavailable. Again, the implications here are wide ranging. So there are many other things, which I think needs to be fixed with sort of the Internet -- freedom agenda. They may need to be done differently. So I do not really have -- I do not disagree with the fact that we need to use the Internet to advance and augment in front of democracy. To me that's a given. The question here is exactly we need to do it and where the emphasis should be. So far there is very little in Clinton's speech, for example, that she gave months ago, about trying to rein in some of the American companies which also supply a lot of Sarbanes to those regimes. It's all very forward looking, all very foreign-looking. What they want to do is basically ask the Chinese not to block access to certain websites or not to engage in cyber attacks. So the first Clinton speech actually sat and I think I'm quoting by memory here that any country that engages in cyber attacks should face the -- should behave according to the rules of international community and they should basically be reprimanded for doing that. And, of course, six or nine months later emerges that NSA and various other agencies have actually been launching a lot of cyber attacks. Many websites or Jihadists without consulting anyone without even consulting Congress. So there's a lot of stuff that needs to happen domestically to make America promises and intents sounds credible. That's the same kind of problem we've seen in American reaction to WikiLeaks, where you have someone like Senator Lieberman who actually happens to be a member of the Senate's Internet Freedom Caucus, who on one day would say that we need to promote Internet freedom, and then he would be the one placing the call to Amazon asking them to remove WikiLeaks files off their servers. That's exactly the same tactic that the Chinese officials would use when they don't want to see certain searches also on Google, see certain files hosted by Chinese companies. So there's a lot of stuff that needs to happen domestically to make America sound credible on the subject. So far there has been a lot of talk by diplomats in Washington which have not really been backed by serious [inaudible] action, both domestically and internationally. And I think this is something that needs to happen very soon. Another troubling aspect that I've noticed while working in this field, even as a practitioner, was that the governments actually authoritarian governments were not as eager to engage in censorship as they were eager to engage in propaganda. I think that's also a reflection of the kind of view the centralized Web that we see. The problem is that if you are in China, and if you publish something critical on your blog, if it's something really critical and something newsworthy, chances it will be published on hundreds of other blogs. And if the government suddenly starts going after you by blocking access to your URL or by forcing blogging company to remove you, it will probably confirm all the accusations you make in the blog post, because it will indicate that the government has something to fear from a blog post. And that will result in more people reposting that, something that those of you who follow Internet [inaudible] know as the Streisand effect, usually attempts to get something off the Internet backfire and result on more attention being paid to the subject. I think what happens instead is not that the government engage in censorship but simply they try to discredit the authority and the reputation of the person who published that material in the first place by accusing them of being CIA agents or Mahsad agents, or basically being crazy or irresponsible. And that happens often by having governments dispatch their own bloggers, dispatch bloggers who are friendly and loyal to the government. We actually are seeing in a lot of countries whole blogging armies and contingents who are there only to promote and advance a particular political ideology on line. And the government actually likes them. And often it's done in the centralized manner. There is one estimate that I've seen that in China there may be as many as 200,000 bloggers who may be at various points trained or paid by the government to advance their own ideology on line, right? And often it happens in the common section of law, because often it happens when something critical is being published and needs to be reacted against immediately. And there was an interesting quote from a Chinese official who handles their propaganda in the wake of the protests in the Middle West. He said that their rule of thumb is that if something critical appears on a blog about the Chinese communist party, it needs to be countered within two hours. So if they don't counter it within two hours, it means they're losing, they're losing the fight. So that, of course, in itself then triggers a lot of demand for data mining solutions, for example, which would be able to identify [inaudible] and what people are writing about in the near time so people will be able -- people the government-paid bloggers can be react in real time. So there are a lot of Chinese companies actually offering various data mining services to the government. One of them I found an interview with one of them and he boasts that thanks to his software, the government can now employ only one [inaudible] where previously they needed 10. And I'm pretty sure the other nine have not been unemployed, they've just been shifted to other tasks where they perform more analytical functions. But this idea of governments actively manipulating public space and manipulating public opinion by dispatching bloggers who are presented as genuine voices of the people, I think is increasing and it's increasingly disturbing as well, because it will, I think, replace more traditional ways of censorship. And to make it a little bit more relevant to the current events, and I think this explains why we are not likely to see something like what happened in the Middle West, in China or Russia. The middle western regimes. I'm talking mostly about Egypt and Tunisia they have not really developed a sophisticated Internet control apparatus beyond just sensor ship and beyond beating our bloggers. I mean, they particularly in Egypt where the government may have had all the tools for the target inspection and many other practices, we don't know if they ever used them, but we didn't see the active shaping of public opinion to the extent that we have seen, for example, in China or we have seen in Russia. It would be very hard, I think, for a group like the one for Facebook group like the one that galvanized people in Egypt, to stay on line for more than six or seven months as, again, it was the case in Egypt on the Russian or Chinese Web calling for active protests against the government. So in some sense you can actually argue that one of the reasons why Mubarak and [inaudible] lost the fight because they were actually unprepared to go and fight actively online instead of just shutting down the websites. And that's not what is happening in Russia. It's not what's happening in China. To a certain extent that's not what's happening in Iran where there's increased effort to, by the government, to beef up their own information warfare and to have people engage actively and counter actively. All sorts of online initiatives aimed at destabilizing it. So I'm not sure if the Google executive who was playing a role in the protests in the middle west, whether he would still be a credible figure if he tried to do those protests in China. There would be something on him that would be all over the Web in China, within a few days or a few weeks. So this is also something that I think we need to be very careful about. But overall, I think the situation is actually getting more troubling since those protests, because now it's not just Iran. Now we actually have seen cases of governments and regimes being overthrown with the Internet playing some role. And the fact that Mubarak shut off the Internet, I think it would be interpreted not in ways that most pundits in the west interpret it; that there was basically a futile act and it was useless. I think most [indiscernible] indicate he did it too late when he basically had a lot of people in the entire square. And I think that will actually lead to more of them trying to consolidate their control over information infrastructure and also to develop an Internet kill switch. And ironically again to link it to domestic American policies on the very date that Mubarak shut down the Internet, a couple of American sanitary again reintroduced the idea of an Internet kill switch, which again would then serve as enabling factors to any other dictator who basically wants to shut down the Web. As long as it happens in America, it looks like, okay, for anyone, because you can then point to the American experience and say, well, if democracies do it, why can't we? So there's an emerging need, I think, to connect domestic Internet agenda, particularly as we start entering the debates on very sensitive subjects, from privacy to good target inspection, to net neutrality. We need to link all of that to the foreign policy implications and to foreign policy agenda. It will be very hard for America to look and sound credible on subjects like Internet theorem in the eyes of the international community if we are limiting it at home. And if we are allowing for more, for example, traffic inspection. Because if we are entering an age where you will see more and more analysis of what kind of data passes through networks, of course it will then again be an enabling factor for dictators in Iran or China or anywhere else to have the same capacity, but them to use it for political purposes, as they very often do. So I think I'll stop here and we can then have some questions. I'll be happy to take any. Yes? >>: [inaudible] was a lot about the opposite of sharing information. I'd say. But if you think about countries that are the most open, what are the benefits for the country and what are the benefits for the citizens? So rather than starting with a problem, have you put some thinking in that? >> Evgeny Morozov: I think that case is very well established in economic theory and elsewhere. Sure, it will lead to better, it will listen to more efficiency in the markets. With better price signals. And so to me that case is very easy to make. And also very easy to make in terms of governance and democracy, because in most cases he has transparency in the political process does help. You do need some checks. I mean, you do need responsible system like Freedom of Information Act. But the reason I'm not tackling that subject, why I didn't write a book about it, is because it seems to me like it's a very farfetched scenario that that would help in a country like China, Belarus or Iran overnight. And it wouldn't. Actually, very often governments would use theoretical openings, and they would use the rhetoric of e-government, for example, of them providing services to citizens, as a way of generating legitimacy, because as many people if you give them a form to complain on line, they feel something democratic happened. They feel as long as they have a form to fill in, that that makes their government look democratic. They actually do see, particularly in Russia, to me it's a fascinating question, because you have this split between the regions and the capital and what happens in the regions is not often known to the rulers in the capital. So the government needs to find an effective way to build a system in which it can actually learn a whole day about that stuff and crime and bribes and whatnot that's happening in the regions. So for them they actually welcome such systems. Actually one blogger is often to go and publicize corruption locally. Often they would take action on it. You have now an established practice of bloggers in Russia complaining in the comment section of the [inaudible] blog, and then they would act on one or two of those complaints, which, of course, will create the solution that people are being listened to and that -- and very often maybe they are. I wouldn't doubt that there is a bureaucrat somewhere, if indeed the security service reads all those comments and then dispatching the information to his bosses about what may be happening in the regions. So it's more complex than that. Again, the questions of openness, when you apply them to authoritarian and closed societies, they tend to have a very complex political meaning behind them. Very often those governments embrace openness for strategic reasons, but it's a fake kind of openness. And talking about it in the abstract, to me the case for openness and democracy is well established. So there isn't need for another [inaudible] yes. >>: Only 60 people in Iran using Twitter. Why are we even bothering talking about the impact of the media if there is no impact? We're only creating a means for the government to actually track everybody who is involved in it. But in reality it doesn't help that much. >> Evgeny Morozov: Well, so the question was there were only 60 people who were using Twitter in Iran during the protest, why do we even bother talking about the impact of new media, right? >>: Especially because in addition we afford the government an opportunity to track the people that are working against them online. I'm an activist, I'm a protest, everybody come and meet me somewhere. Now the government knows we're going to track this guy. At the same time it's not very effective because only 60 people are using it. [inaudible]. >> Evgeny Morozov: Well, okay, I should word it that way. The fact that there were only 60 people in Iran on the ground who Aljazeera could find using Twitter it does not mean that Twitter Facebook couldn't use to mobilize people effectively. They listened to them and suggested there could be. Again, I think it would be premature to draw conclusions about the causality on the ground who caused what and who did what. I think at this point the reason we spend so much time talking about the Internet and Facebook and Twitter is because they are the most visible factor. And there the factor that all of us can relate to, even if we know nothing about Egypt, even if we know nothing about Tunisia. Very few people can talk with some level of understanding about the role of Egyptian trade unions in the revolution simply because few of us know about Egyptian trade unions. But it's very easy for us to talk about Facebook groups. And of course we don't actually have much data about Egyptian trade unions either. And we'll have it only in four or five years. So for me it's normal we spend so much time talking about new media at this point. But I think there is something different that's something which I try to address in the book and how we talk about technology. There is something that make a lot of people think that it does have an inherently liberating potential, and that the information itself has an inherent liberating potential. And I think that bias may stem back probably from the time of enlightenment, where, of course, there was a lot of -- there were a lot of assumptions about deliberating nature of information and knowledge and so forth. And I think a lot of those assumptions now do make an implicit appearance in many of the arguments about the role social networking or blogs could play in those countries. Whether we should continue talking about it, I think we should, in part because I wouldn't argue that it's a complete myth, it's a complete invention that -- the activists do use those tools, and many of them go to jail for that. I think those tools do have -- they can make a contribution that is not available on other [inaudible] it's very hard for you to reach 600,000 people in Egypt and tell them where they should show up for the next demonstration within an hour. You can maybe do it within a week, through word of mouth. There are very concrete benefits to social media, which I think we need to understand. But ideally we need to be very critical in terms of how these tools may be ultimately transforming not just the culture of Sarbanes but also political culture in many of these countries. I spent a lot of time in the book sort of thinking through how now the fact that so much activism happens on line, may actually make the goals that activists are pursuing harder to achieve, because for many people, pure speculation on my part, but I think for many people, the point of online activism is not really in achieving certain goals. It's in looking cool in front of their friends and showing that they care about saving the children of Africa or climate change, pick any other subject. And it's about feeling good about changing the world and often changing the world, that feeling you can get just by signing a petition or joining a Facebook group. There is very little that needs to happen afterwards. In Egypt, it was actually, I think, they were very lucky that people were willing to go out and protest, but I don't think it was driven by Facebook. The eagerness to go out and participate against Mubarak. There were many factors, many of which we still don't understand. It was not because they were mobilized via Facebook, they actually reported to the streets. If anything, the fact they were mobilized by Facebook suggested otherwise, that they wouldn't go and go and change Avatars to green, that's what happened in Iran. I think those questions need to be raised because very often and talking about my own country, about Belarus, I do see a lot of young people who have this very idealistic view of online activism where they think they can actually change the world, change the government just by joining Facebook groups and just by blogging. And they are actually eager to disregard the existing political movements and the existing opposition movements. Many of which are, by the way, completely ineffective. And if I had to choose whether to join them I myself would probably think twice. But I don't think that you can change the political environment in kind of like Belarus solely with digital activism. And to me the fear is that our celebration of new media as a form of activism may actually create the separation between the off-line activists who are very ineffective and getting old and getting older but eager to go to prison and get beaten up and participate in off-line rallies holding placards in front of the police. And the younger generation who would still be very keen to do things online. Again, it may be that I'm overstating the differences. But when it comes to policy, and this is my main interest in the book is actually a policy, how [inaudible] translate into thoughtful interaction by government. Think about it from a policy perspective, it's not really certain that what the state department should be doing now if it wants to bring democracy to Kazakhstan or China is to pour old money into getting groups on Facebook. Because that's the last thing that people would draw from the Middle West. If online activism works there, let's just go set up trainings and train everyone in using Facebook in the Middle West or Central Asia the caucuses. When you start thinking about those opportunities with sort of opportunity costs, many other things in time you do become more skeptical and cautious, because yes it's great to celebrate social media as a means of often engaging in protest. But it just wouldn't work everywhere. And I think we have to start our assessment with the political and social conditions on the ground and not with some inherent features of social media, when you think about resource allocation. So this is kind of a glancing answer but yes. >>: You mentioned that Vietnam is building their own social network. >> Evgeny Morozov: It launched. >>: Launched. This sounds like an arms race that is the exact kind of bankrupt of the Soviet Union. Right, you have -- in America these things, right, these companies are actually making money. And so they're going to keep innovating, and there's going to need to be the constant need to keep copying them whereas in countries like Vietnam, you're going to be spending a large amount of resource in many cases losing money. And it would seem that this is something that's going to bankrupt governments and possibly be good. >>: You know, I wish that were the case, but they do find ways to make money. I mean, not all of them have credit cards, but all of them have mobile phones. So you charge people for -- you know to me there are some countries where you actually charge people for looking up who has looked at their profile, right? So to know anyone who has looked at your profile you actually have to pay up Y [inaudible] amounts. There's way to monetize those networks. I can't speak about the sustainability and profitability of that network in Vietnam, but lots of similar sites and projects in Russia or China are very profitable. Not all of them are state-run. And, again, the state ->>: I think you have to differentiate the large markets where this strategy may be bible. China has its own social networking site versus it's smaller countries where ->> Evgeny Morozov: Sure. I agree with you. And what I'm trying to say is that in the case of Russia and China and they actually have a slightly different strategy where the government does not try to build around social networks. They already have domestic companies that are doing it pretty well. They're just trying to favor them indirectly whether it's by giving them better attacks environment or not sending tax man to examine their doctors as they would with foreign companies. More and more often. So I didn't know how far they would go and how much money they are prepared to lose. To me it seems that profit in Vietnam at this point for them is not the main concern. Right? So they may as well write it off as some kind of a political tax that helps keep people busy and not out in the streets. So I just don't know how far the governments would go in tolerating their losses if such group size proved to be unprofitable. And, again, I don't know how many people they will need to run them, eventually. So it may be that they'll be fine with 200 people. It may be that they will near 2,000. A lot of them are quite okay with stealing technology from the west. So it's not like they need to run their own research labs. But, again, it's pure speculation. I just don't know what are the figures involved. I wouldn't doubt their capacity to monetize. >>: The online lawsuit, is the Microsoft Corporation, online services division. >>: Particularly good at that. >>: We are a world leader in losing money online. [laughter]. >>: One more question. >>: So have you tried to bring in the old guard and the new guard together? >> Evgeny Morozov: I don't get involved in politics myself. So I don't serve as a convener. >>: You were an NGO. >> Evgeny Morozov: I was. I do a lot of work for George Soros, by his Open Society Foundation. I do what I can. But the problem there is generational and there are a lot of people who just don't want to work with the older guard, because they do think that there is an entirely new world out there. Even if you look at [inaudible] the Google executive in Egypt, who, he used to do much business with the established actors and he refused to get offered funding to help them run the Facebook group a while ago before the protest started and he deliberately said no, in part it would jeopardize their status as a grassroot organization. If you're a group of cyber activists in Tunisia in September openly challenged the United States and their Internet freedom policy. They opened up and spoke out about the United States entering the space, activists with tools and they said we don't want any money from America. We are happy on our own, very cheap to do online activism and we don't want resources. We don't want our governments to use American support form of activism as an excuse to discredit us. That's not how the old guard thinks. Because in part what they do is far more resource intensive. Many are on professional organizations, they have staffs and offices, and that's also part of the clash that they have. In some sense, those who celebrate the Internet in this respect [inaudible] there are ways in which you can now do a lot of things on the chip, and that lets you get away without any institutional affiliation. But it's not how the older political and social groups work. Many of them, think of the countries that had dictators 30, 40 years and no position has been there for as long. They have already become -- they're no longer the kind of up and coming political entrepreneurs said they were sort of years ago. Now they have structures and it's very hard for the young people to deal with them. So it may be that they will just die off but I doubt it. In part because a lot of young people joined them. Just for career reasons and some were -- I know you look surprised. But, again, I don't want to enter into politics here. But for many people being in the position it's a nice career because you get to travel quite a bit. All right. >> Kirsten Wiley: Great. Thank you very much. And books are ready if you want to sign them. >> Evgeny Morozov: Thank you for coming. [applause]