>> Phil Fossett: So good afternoon. I'm Phil... the Microsoft Research Visiting Speaker Series. Jordan is here...

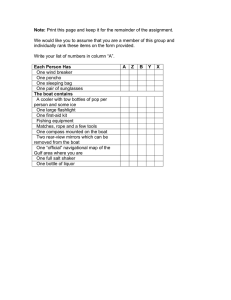

advertisement

>> Phil Fossett: So good afternoon. I'm Phil Fossett. I'm here to welcome Jordan Hanssen to the Microsoft Research Visiting Speaker Series. Jordan is here today to discuss his book Rowing into the Sun, Four Young Men Crossing the North Atlantic. Jordan and four college friends rowed in the first North Atlantic rowing race and won despite several big challenges. There are several challenges in this thing but I'm sure they are big. This is fairly a huge thing to do. Several years later he turned the vessel into a rowing science machine, oceanographic gathering data as they rowed. And they wrote photographed films and made the research readings and findings available to students and public before some disaster struck. Jordan Hanssen graduated from UPS, support his dual passions for travel, writing anyway he can. He's written guides, coached rowing and been part of several interesting expeditions and I've been a rower myself, so I rowed at Seattle Pacific for three seasons so I can somewhat relate even though our boat was a little lighter and a little bit different than the one that's in the book, so please join me and we'll give Jordan a warm welcome. [applause] >> Jordan Hanssen: Hello everybody. Blow the conk first. I can go little bit louder, but I figure small area. [laughter]. My name is Jordan Hanssen. Thank you all for having me here at Microsoft. My story starts at a little house in Seattle over in Wallingford, or actually just about a mile south at the boathouse at Lake Washington Rowing Club. I graduated college in 2004, and I had two passions. I love to travel and I love to row, and I decided that I was going to pursue rowing to see how far I could take that and see if I could get on the national team. I chose rowing because if you are going to train on that level, it's kind of a monk like lifestyle. I started doing that and about two weeks in, this poster appears on the boathouse wall, and it was of a boat that looks something like this riding down on a very big wave and I thought to myself, what a great way to mix both of my passions. I can row and travel. So I went back to the guys that I rowed with in college at the University of Puget Sound and I asked three of my friends and all three of them said yes, with just a very little bit of reservation. But we all moved into that house together and we spent the next 18 months planning. As we were planning this, we were looking for, you know, we wanted to do this adventure. We wanted to race and we wanted to win, but we wanted to add another kind of just some more heart and value to it, so we decided to raise money for the American Lung Association of Washington in large part, mainly, you know, rowers use their lungs, of course, the whole athletic side of things, but also because my dad died of asthma when I was three. These three guys came to me and said why don't we name the boat after your dad, so we named the boat the James Robert Hanssen. And over this period of 18 months we really had no idea what we were doing. You know, I'm a history major. Some other guy majored in geology, international business and IPE which he describes as learning how to read the newspaper, and we went to all of these people in Seattle and said we're going to row across the ocean and these people thought to themselves if I don't help them they will die. [laughter]. We managed to I guess be earnest enough that these people really volunteered an incredible amount of time and when we showed up in New York we had a boat that we felt compared to the others was the best and enough more boat that we wouldn't want to cross the ocean in any other boat that showed up in New York. June 10th 2006, we began rowing across the ocean and I found out that I get very seasick. I also found out that I can row and vomit at the same time. [laughter]. It was incredible. You know, we are leaving New York and it was actually the 30th anniversary of the Liberty Landing State Park, so just as we passed the barons under Narrows Bridge, that's the last piece of land that we can see and just as it gets dark all of these fireworks start coming up from New York and that was our last view of North America. We are rolling along, puking, getting over it, gradually evening out and day three rolls around and it's just dead calm. There's this perception that when you get out on the ocean that there's just this constant, you know, these big waves that are moving all the time and it's really deep ocean and it is this weird place where it's just always active, but sometimes it's absolutely dead calm and this was one of those days. We look down and you could see your reflection in the water, just the oars, that's all you could hear is just them clunking along and it was hot, about 95 degrees, 100 percent humidity and I hear something and I can't really register what that is, so I turn around and I see this line of white water stretching all the way across the horizon and I tap my buddy Greg on the shoulder and I say, do you have any idea what this could be. And he gets the other guys Dylan and Brad out of the cabin and they just have no idea and we are all just kind of sitting there watching this and it gets closer and closer and all of a sudden we can see these little black bodies that are leaping out over the water and its dolphins and its thousands of them and they are everywhere around us from horizon to horizon and we're right in the middle of it. So they are just stampeding straight through and we just have no idea what they could possibly be doing and it turns out that the farther you go out to sea the bigger these stampedes of dolphins can get and they were just basically chasing after food. They didn't hit the boat. They could, you could just stare down at the water and just see them stacked like 15 feet down and you could hear them and that was the most overwhelming thing. Here they are all around us and it just sounds like 1000 flippers just chatting to each other as they are ripping across the sea. Later that afternoon we got this e-mail. Here we go. That's kind of what it looks like. Later that afternoon we got this e-mail because, you know, we have internet in the middle of the ocean or at least we did, saying that tropical storm Alberto was not going to change course and it was going to continue to increase speed and hit us in the next 48 hours, so we rowed and rowed and rowed until the waves got about 10 to 15 feet tall and then we put out our sea anchor which is a parachute that sits in the water and has about 200 feet of line. So if this is the boat and this is the parachute it kind of holds the bow under the waves so if you have like really rough water that bow is crashing through them, so we all hold up in the stern of the cabin. And the stern of the cabin is about 8 x 5' and if you want to get an idea of what this storm really looked like, it's something like this. [laughter]. This is probably the best part about having done something like this is that sometimes when I go speak to schools I get thank you notes and they look like this and that's pretty awesome. But yeah, we were in that little cabin sitting there sweating for about 19 hours and once we finished it was, you know, we came out and it was almost like the only way I can think of to describe it is it was like there was a bathtub full of toddlers and they were are you moving around and all of a sudden you pull them out and there is still that energy and the water but it's very slowly dissipating but it's on this absolutely massive level and so these were the biggest waves that I have ever rode in but they were just very gentle and just throwing us up on these little blue hills and blue valleys back and forth and you would get up to the top and you could just see really far in the distance and then you would go down and then the wave was over there and it was the size of the house. And eventually, it just slowly calmed down and we were eventually back to just rowing the ocean. It was a race and our strategy was the Gulfstream and I promise you this is the only time I'll do the reading presentation. I well read a little section from my book. The Gulfstream is born from equatorial water driven by the sun's heat and east wind into the Gulf of Mexico before it starts its journey up the eastern seaboard of North America. Somewhere between the latitude of Charlotte in New York, the 60 mile wide current meanders toward northern Europe at up to 5 knots throwing off equally strong and constantly changing eddies 150 miles long and as wide as the stream itself. On the pixelated thermal maps downloaded via satellite phone to our onboard computer the Gulfstream looked like a breath of red and yellow fires streaming into the cold blue North Atlantic. This natural phenomenon is the reason that London has a warmer winter than New York even though it is more than 750 miles closer to the North Pole. Harnessing its power would fling us towards our final race destination in England. Getting caught in the eddie would slow any boat, especially one without engines or sails. 17 days into the trip a with tropical storm, lightning and a stampede of dolphins under our belt, but no sign of our swift current an even larger problem was about to reveal itself. After I finished my two hour turn at the oars, sleep remained elusive, my body unable to wind down. I stared up at the note duct taped by Brad to the white bulkhead and read it for the hundredth time. Courage is starting the race with no end in sight. It was from Brad's mother. Brad shifted uncomfortably next to me in the cabin. He spoke clearly but his meaning didn't register at first. "What was that?" I asked. "I need to talk to you about the food." So on day 17 my good buddy Brad who I am out in the middle of the ocean with with three other guys and who was in charge of the food informs me that at the rate we're going through it we don't have enough and so from that point we have to make a lot of tough decisions. That's in the book. But there's more. A few years after I get back from rowing across the ocean I get the itch to do it again, but I've already done it so why? Why should I do it and what am I going to be able to ask people to help this time around? The first time I mean it was a pretty easy narrative. Four young guys just graduated looking to do something big for the first time in their lives, but at this point what was going to do it? What I noticed after this trip, once I thought about it, is that I had a lot of opportunities to talk to kids and had a lot of opportunities to answer questions. People were curious about it when they would find this out about me and I figured why not turn this into, turn this vessel into a science vessel and put some specialized equipment on it so we could basically take the pulse of the ocean as we're going across and then partner with some people who knew how to create curriculum and create curriculum that would come out concurrently with the adventure. So I was able to convince some other rowers, including my friend Greg from the first trip and more importantly, the Canadian Wildlife Federation who underwrote the expedition. So I had a new crew. My buddy Greg who is there leaping through the air, myself, Adam Kreek, he's a Canadian gold medalist and Pat Fleming who is another guy who I rode with in college and if any of you guys ever go ski up at Crystal he is a wilderness EMT up there on ski patrol. Anyway, we realized, Greg realized that it was going to take a little bit too long for him to stay away for this particular trip, so he jumped ship and became our shore manager. And we picked up one of the most relaxed people I've ever met, over in the corner, Marcus and we trained, did some safety training. And we turned our rowboat into a science vessel. We pretty much quadrupled the power we could create on the boat. We had about three times the solar panels and a wind generator onboard, so this was mainly, the most important thing that the power was making was water, but it was also powering about $40,000 of scientific equipment, which is temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen and dissolved CO2, pH, turbidity that was basically running with a little pump all the time, so it was logging all this data and every 15 minutes it would send a stream back via one of the satellites on there. So a few of the other things we had on there. This is our satellite dome. This allowed us to send back video and images,blogs and pretty much anything else. Then we had, this is our AIS antenna. When we turn this on it basically sent out a little message to all of the boats around us saying we are here. This is what we are and please don't hit us. And then VHF radio and then we had three GPS that were hardwired. This little guy right here is a air morrow [phonetic] weather station, which basically, you know, does the barometer; these are the variety of points that were also being logged. And we decided to do a training trip around Vancouver Island and that's what a rowboat looks like in the middle of the ocean. Saw some cool things out there, surrounded by a pod of whales; that was pretty extraordinary. And this is kind of, this is what the data look like when we got back, some of it at least, so you can see right here this is the temperature and you can see that it's about 3 degrees warmer on the outside of the island versus the inside. And what was fascinating was to go into classrooms and to talk to kids and to just kind of ask them questions about, you know, why is this a case? And most of the time it was very rare where someone would say well, it's because there's more freshwater, because you have more snow melt on either side and it's the snow melt that's dropping the temperature and it's also if you go to the salinity up there you'll see almost the exact same pattern. And just kind of communicating to kids that water flows downhill and so that everything on land eventually washes into the sea, it was then just amazing to see that something that I felt was so simple needed something like this to be explained to it. So our big trip was going from mainland Africa Dakar to mainland USA Miami. So we headed off to Dakar and our boat ended up being about 30 days late as we learned about the intricacies of shipping to the developing world. It was pretty exciting. And then, yeah, we began our trip across the ocean. So there we are again in our science vessel heading out and this is what ocean rowing looks like. One of the things that is a little bit challenging out there is when you see these oars, they are pretty big. It's a piece of wood, in this case fir wrapped in carbon, so it's a really substantial oar for anybody who has rowed. They are very, very heavy and occasionally, especially on days like that when the wind is coming from the beam, some of those oars will just get grabbed by the waves and then slammed into your shins, so there's some of the wounds that we got as well as the blisters. Our blisters were never really that bad in large part because we had very large handles for the orders and they were large wood handles and we found that while your hands hurt from rowing 12 hours a day, they weren't torn apart and anybody who has rowed if you've rowed on plastic handles, that stuff just rips your hands to shreds. One of the other studies that we were doing out there was a sleep study, so two to four times a day we would take two surveys and we got good enough that one person could just crack them off at the end of each shift and fill out the buttons. We had our CTD. This is conductivity, temperature and density. Drop this into the water twice a day and it basically takes a profile of the ocean for about as deep as you can drop it. In our case it was between 50 to 75 meters. Here's Adam working on our little tough books. You know, that was pretty much what we did every day. We rowed for 12 hours a day in shifts of between one, two and four hours and then we cooked, kept the boat clean and made sure all of the scientific instruments were running, wrote blogs, edited video, pictures and we sent all of that back, so we had a pretty busy schedule. Often it was interrupted by a little flying fish that would cruise over our boat and in the morning we would have a few. I'd pick them up off the deck and if they were about this big I would just eat them and the amazing thing about these guys is that they like, it's not like they're leaping really far. These guys are flying. They jump out of the water and you'll see them glide up and over waves for up to 400 meters and sometimes they'll drop down into the water and these big fins right here they'll extend them down and so they would just kind of hover on top and just build up a little bit more energy before they ramp up off another wave. We thought that was pretty extraordinary, but we kind of expected to see flying fish. We didn't expect to see flying squid and I'm sitting in the cabin. [laughter] Marcus is, they were both laying down. It was just one of those afternoons; it was hot as hell and, you know, you are out on the pad, we're outside and then oh wow! A squid just flew up on the deck. And at that point we started seeing these little squid that were about 6 inches long. They couldn't jet quite as far as the fish, but they would definitely fly and the way they would do that is they had their little fins on top, but they would take their tentacles and make another set of wings on the bottom and they could fly about 100 meters and they would jet in groups of anything from a random one to two dozen just leaping from wave to wave, and the reason they do that is it's just more efficient for them to, once they get going a certain speed the drag coefficient is such that it's easier for them to just pop out of the water and glide than deal with being underwater. One thing I noticed on both trips was birds every day and that's I think one of the neatest parts about being out in the ocean. I think people who are really into birds or who are really, really into birds and I have never been one of those people, but out on the ocean it is something extraordinary to see just nothing but ocean for months and just always know that you are going to see a bird. Meanwhile, back on shore, this is Greg. This is what he was doing. We would send him information. We would send him data in all of its various forms and he would basically send it to the Canadian Wildlife Federation. He would send it to our education guys, the media, and so he was taking in all of this data and he was working just as hard as we were to bring all this stuff back. This is life at sea. This is the middle of the shift change. Marcus is sitting there doing some dishes, just kind of a constant. This little leatherback turtle came to visit us. This guy was about 5 feet long and that's Marcus. So I was rowing one night and I had this, in these four hour shifts we take the middle part of that shift and we do some stretching and calisthenics to kind of balance out rowing for 12 hours a day, and I was sitting there stretching while Marcus was rowing along and a squall had just passed overhead and the moon was just exceptionally bright. I mean it was one of the best things about being out there. The stars are just incredible. The moon is extra bright and it's all the time as long as there's no clouds. And I look back and I saw this funky looking cloud appear on the horizon and I thought to myself that looks like the beginnings of a rainbow, but you must be hallucinating because it's midnight and you have been rowing for about two months. And I'm sitting there and keep stretching and I'm looking up again and I saw this thing, this grey rainbow extend all the way across the horizon and it turns out that moonbows exist. They are a real thing. They are well documented. It's just that not many people know about them. And it was absolutely incredible. So the evening of day 72 rolls around and Marcus and I are sitting outside and there is a big lightning storm and we're sitting there and it's just getting absolutely soaked and so when the lightning flashes it's just so bright that off our jackets it looks kind of, everything looks sepia toned. It's a very weird, just this very weird feeling. The difference between the North Atlantic and the mid-Atlantic, the North Atlantic was a lot more volatile. Things were, you know, you never stay on sea anchor for more than, you know, 20 hours and quite often it was just for six and then something would change and you could make progress again. On the mid-Atlantic everything just moved a lot slower, so when weather it would come in it would stay for 48 hours to five days, so out of the 73 days that we were out there, we probably spent almost two weeks on sea anchor just not going anywhere. And Marcus and I were sitting there on sea anchor, lightning was going around and then finally the lightning passes and we can start making really good time and the reason we chose the Dakar to Miami was because to take advantage of the Tradewinds and that current up there, but that really wasn't, that might have been the case in terms of how you make your prediction, but the weather that we had that year just wasn't in our favor. So things started to move at about 11 o'clock that night and they were moving really, really well. It wasn't too rough. We went to bed at two. Adam and Pat had gone on and we were making really good time. I woke up about 12 minutes before my shift, which was kind of weird. The longer you get out there, the more used to it you get and then the less sleep you end up needing, and I got outside and it was a brisk day. You know, winds between 20 and 25 knots and waves between four and six feet and keep in mind we'd been surfing down waves that were 12 feet the week before and everything was fine, so I'm talking with Adam and Pat and finally this stuff is going, and everything is going in the right direction. We make our shift change. I go out and I replace Adam on the bow section which is also the steering section. Marcus replaces Pat and instead of starting rowing he starts his morning constitution on the 5 gallon bucket that served as our toilet on the boat and Adam and Pat start making their way into the cabin and they're getting settled. So we're cruising along. I'm going downwind and I see these two waves that look a little bit different than all the other waves. They're not particularly high; they are just shaped differently. Most waves are shaped like triangles. These are shaped like squares and they had flat faces to them and they are very close together, so I turned the stern to face these waves which is how you want to take a big wave like that and many things start happening at once. I'm on the oars. Marcus is on the bucket. Adam is laying down. Pat is reaching out to close the door and this first wave overwhelms the stern of the boat, and it's not violent; it's just very strong and it starts dumping water on the gunwales. Instead of lifting it up, it just goes all the way around the stern and starts pouring water on the gunwales, dropping about, you know, 2 to 4000 pounds of water on the deck and you have these scuppers along the side that are shedding water. There's about 10 of them and stuff is pouring off the gunwales but the boat is listing as the second wave hits. So the boat’s 29 feet long and these waves are about 30 feet apart, so that second wave grabs it and shoves the bow into the back of that first wave and just spins us into the middle of the ocean and right as Pat is closing the door and so he can't get the door shut which is what keeps the boat self righting. So I get thrown into the water. Marcus is caught with his pants down. Adam’s inside the cabin and he has this weird realization where he thinks oh, I can't breathe water. I've got to get out of here and then he freaks out as he realizes that Pat also cannot breathe water and Adam is huge, absolutely massive human being and Pat is about 155 pounds and he just throws Pat through this cabin, goes up to the top, you know, the deck of the boat which is now the ceiling, takes a deep breath and dives out. And all within 15 seconds I see three other heads pop up and everybody’s okay. And it's, don't even have time to be fearful at that point. We check in with everybody. Knowing this boat, I know that it's really unlikely that we're going to be able to flip it back over with that cabin flooded. So we get, each of our life vests has something called a PLB personal locator beacon that's attached to them and Pat said how many do we turn on? And I said all four and that's -- it's about 6:05 when those go off and about 5 minutes later Greg gets a phone call from a guy named Chris Harper who is a petty officer in the U.S. Coast Guard. Greg knows that something went down when he gets this call at about 3:15 in the morning and he starts sending this guy Chris every single piece of information that he possibly can to give them all of the tools he can to help them find us. Three beacons registered, although we thought we set off four. Greg tells them, you know, we had a yellow break which is a system that basically gave our location on a daily basis. We had two VHF radios, satellite phone, satellite dome and they try every single one and they can pick us up. So meanwhile, we're back in the water and we get our life raft out, tie it to the bow of the boat and check in with everybody again. Everybody is in a really remarkably good spirits considering we spent four years on this project and it is now upside down in the middle of the ocean. We are actually just outside of the Bermuda triangle and we spend the next three hours working with whatever we can, the oars, the ropes, the dagger board and try to flip this boat over and we get really close, but then after hour three it starts to get cold and we hop in the life raft and start waiting. And we are going through, so on a life raft, it has a certain amount of supplies. It also has, we also had a supplementary grab bag, extra water, extra food, you know, all of the kinds of supplies that you need and the life raft, you know, we got a really good one, made sure it was well outfitted and we start going through and kind of checking to see what kind of tools that we have because we don't know how long we're going to be out here. So we check through all of these things, you know, the food, the drogue and all of those things and there's the little Bible, which is inside. And, you know, we're sitting there and Marcus just kind of passes it around and we all have a good laugh and then Adam looks at Marcus and he goes well, it couldn't hurt. So he starts reading Genesis which is two lines and at the end of that the Coast Guard comes, so this is an HC 144 and this is what it sounds like when the Coast Guard comes. Just kidding. It doesn't really sound like that. [laughter]. Yeah, but it felt like that. Pat goes absolutely nuts and he goes we're going home and it might be today. [laughter]. And they proceed to start throwing stuff at us. So the first thing they drop is some life rafts and they throw a steel barrel the size of the keg that has a lot of equipment in it and so we're just blown away at how accurately they are dropping these things, that if they hit us could kill us. And Marcus goes and swims for this barrel and he brings it over and it's got a wool blanket, six emergency drinking water packets, six chem lights and two emergency food packets. So we're thinking what we really need is a VHF radio and if it was in there, I mean, the Coast Guard’s going to have this stuff labeled. We have all this stuff. If we open this barrel, we can't fit it on the boat and if we open it up all of the supplies could be ruined. It has a certain level of protection that's inside this barrel. We'll just tie it up to the bow of the boat and if we have to get into it, great. We have some extra stuff. Meanwhile, up in the aircraft they are looking down and they go well, why didn't they open that up? There was a VHF radio in it [laughter]. Meanwhile, they are running out of fuel so they have to switch out to a C-130 and the C-130 drops another barrel on us and this one is helpfully labeled open me about five or six times [laughter] and it floats up next to us and we open it up and it has a much more comprehensive list including VHF radio. So we get a hold of them and all of these guys with great Southern accents are on the Coast Guard, on the VHF, so they tell us that the Heijin is going to come and pick us up and this is a 580 foot car carrier. It can hold about 4000 cars. It has about 90 feet of freeboard. It's like a floating castle bigger than a city block, and it's headed our way. We were basically found identified by the Coast Guard five hours after the flip and these guys are going to be, they think they are going to be there between five and six that evening. We're down there, not super close to the equator, but close enough that the dusk is very, very quick. Things need to happen relatively quickly. So they are coming along and talking to the Coast Guard on the radio we want to be in a fairly, we want to seem, what do we need to do in order to be prepared to get picked up in these things? Is there a particular plan? And the words that came out of his mouth were, "I don't know. It's going to be interesting." [laughter]. The reality is if they are going to send us -- basically every single commercial ship and every -- to a limited extent -whatever boat’s in the area kind of by going out to sea you sign up for, you can officially do it but it's kind of expected that you respond to disasters at sea at least be in the area. And they can't know the asset of the vessel, so they can't really make that -- they just tell you. We'll figure it out as we go along. We're too far out for helicopter rescue. That's about between 250 and 300 miles at the absolute max, so this is what's going to happen. This guy is going to come and we're going to figure it out along the way. So Heijin comes and you can see this is the C130 and this is our rowboat and that is our life raft. This is what they filmed for us. So there's the Heijin. The wind is about, you know, 30 to 35 knots at this point. Waves are a solid six feet. That thing is like a giant sail and so it has these absolutely massive bow thrusters that are just churning up water on the side because it's turning to the side as we're getting blown towards it. Actually, you can see here, that's us right there. So the captain of the Heijin gets on a VHF radio and says time to cut loose from your boat. You're going to float towards us and then we're going to throw ropes and pick you up. And we do that and turnaround. I had to have this moment with this boat. I've spent about 150 days in this boat and it's named after my dad, and I think okay. This is my moment. I'm going to have it right now. And then I turnaround and that grey water has turned into the well oxygenated blue water from all the propellers that are getting chopped up, chopping up the water. And our little rubber life raft starts getting closer and closer to the ship. As it hits this blue water it starts racing down all 580 feet just from the wash and it's less than five feet away and you can see just the layers of paint that are at least 20 years old on this thing. You just don't want your rubber life raft as tough as you hope it is scraping up against it and there's about 20 guys that are all dressed in -- it's like this guy in orange and orange and hard hats and they all have these ropes and all 20 of them throw their ropes and they fall short and so they have to reposition this gigantic boat. It takes about 15 minutes and it's starting to get dark. We really only have one more chance for this to pass. So, set it up, do it again, have the same little scary little ride down the side of the boat. We grab one of the ropes and we grab the ladder and so there's about a 45 foot rope ladder hanging down the side of this thing and it's what the pilots use to get on and we grab both of these things and whoever is closest goes for it and I grab onto that thing and the life raft sinks down because you are in six-foot waves and just disappears beneath you as you grab onto that and make my way to the top. Then all of a sudden I'm walking around more than two paces that I can for that I have for the last 72 days and they give us clothing. Some pretty awesome orange jumpsuits and I get into, I get on the boat. I'm in my underwear and I march up to the bridge and I get to talk to the Coast Guard and say we're okay. And the thing that just blew me away is that once the Coast Guard was on scene they didn't leave and so that whole time you just heard that, of that aircraft and it just buoyed your heart like nothing else. You're not lost. You're not lost. I talked to the pilot later and he said that he actually did lose us for a little bit, but then they found us again [laughter]. I mean, here's another dramatic rendering of the rescue. So we were on the Heijin enjoying the hospitality of NYK for about 25 hours and we got to eat lots of food and watch Bollywood movies [laughter]. Then we made our way to San Juan Puerto Rico. We ran into our family and that very next day, so we flipped on Saturday morning at 11:00 PM; on Sunday night we're in Puerto Rico and then the next day we did these 40 interviews. Next two days we start researching what might we, what would it take to get the boat back. And the fact is it's just, there's just no way it's going to happen. I would need an aircraft that could go out into the middle. You would need a big boat, at least a tugboat in size, I mean to basically to go back into the Bermuda Triangle and go get the boat. Wednesday night rolls around and the CEO of the Canadian Wildlife Federation shows up and I've been doing the research figuring out just what are the assets in the area that could make this thing happen. And Wade is this big really nice guy and I say well, Wade if we don't go after the boat, we won't find it. And if we go after it we probably won't. I said I think you should go for it. Next day I was in a 19-passenger turboprop and, with Greg and our photographer and our videographer and we all just passed out for the first hour and a half and this guy, Raul, who organized the whole thing, wakes us up and 45 minutes into this we're down at about 1000 feet and Greg and our photographer Aaron think they saw something and so they start kind of like bickering about it. Finally, they turn around and say it's our plane for the day. We can tell them to turn around. So we tell the captain to turn around and as he does there's our boat. So we were searching in an area about the size of Rhode Island, 1600 square miles and through absolute dumb luck or divine intervention, we found our boat. But it wasn't in our position at this point once we turned that aircraft around, we have a rough idea of where it is but how are we going to get a hold of it and that's where the tugboat Century comes in. We head out. That tugboat goes about 9 knots, so, you know, 13 hours before I get in the tugboat and 2 1/2 days later that search area has grown from, you know, 1600 miles to 0 at this point, 400 square miles. And we start running our search pattern back and forth, back and forth, again, still looking for a needle in a haystack and the first day passes. And the second day passes and I told Greg on the end of that first day, you know, if we are serious about this we have to get that airplane up again just to have a look at to know, so that we know that we are even in the same ballpark. He sends it up and we don't see the aircraft at all that day. And I know when the aircraft is going to take off. I know when it's going to be in the search area. I know when it's going to leave, so there's just little bits of hope along the way and 5:30 rolls around and this tugboat crew which is this awesome international crew from all over the Caribbean. They thought we were absolutely crazy when we got on this tugboat and they still thought we were crazy when we were looking for it, but everybody had gotten so excited and it was just like the energy was sucked out and everybody was just moving slower and more depressed and Carlos just runs out of the cabin and goes the guy with the beard, they found it. It's 36 miles away. It's five o'clock and it gets dark at eight and there's no way we're going to get a hold of it at night, so it's that old math problem. You have a rowboat stranded in the middle of the ocean and a tugboat that only goes 9 1/2 knots and it's three hours till dark. So we go with the intent to get in the area so that we can be searching first, the very first thing that morning, but that means that the way the drift pattern is it's still going to be a 25 square mile search area so it's still pretty darn small considering you could fit four of these rowboats in this room. At about 7:00 AM our captain, our captain who is this, he was a Muslim from Honduras named Israel, sees something on the radar and our photographer sees something on the horizon. They come out and they both point in the same place and they point it out to me and I bring the binoculars to my eyes. I look and I stare for about 3 minutes as we're driving towards it. I hand the binoculars up to Marcus and he nods his head and we found it. There was no, there was nothing on this boat. It was just, there was no beacon that was going off. I had left one, but after 36 hours it was a moot point. We get it up in the air, put it on the back of the tugboat and the best part about this was that Marcus and I had no experience working on tugboats before and it was up to us to basically figure out how we were going to use all of this 97 foot of tugboat full of hardware and get our boat up and so a lot of that was getting in the water with our Speedos and our life vests and rigging it up ourselves and then these guys taking over with the crane. Made it back to Puerto Rico, cleaned it up, we were able to salvage pretty much everything and out of that everything that had been sitting in salt water we were able to recover about 50 percent of that. Cleaned it up and sent it back and it's sitting in Ballard right now and about a week after that I went to Florida and thanked the Coast Guard for looking after us. So that's the end of that story. And what we're doing now is, the whole education thing worked pretty well. It was the first time we did it, but this is where I at least I see our organization OARNorthwest going. We want to be able to do this adventure education so we need, in order for teachers to really find it useful, we need to make something that's consistent and the way to do that is to do some kind of flagship trip, so what we're going to do is create a trip down the Mississippi that can be done by different people every single year, create the same curriculum, work with the same educators that helped bring our curriculum to life out in the ocean and that way you have new people each year that can bring new eyes and sort of fresh enthusiasm to it, but you have something that teachers can rely on and then using that audience that is excited about what we're doing and kind of knows how to use what we're creating, I want to use that to leverage a trip around the world. And that is OARNorthwest and what I do and thank you guys very much for having me and I would be happy to take questions. [applause] >>: Amazing story. So who's sponsoring you now, like are you your own? >> Jordan Hanssen: Yeah, we're our own 501(c)(3) and that was something we felt was really important from the very first. We didn't know what it was going to turn into. You know, we had gotten into this as a race, but we figured we'd give it the bones to do something more and this is what we've decided to do with it. >>: So is it a large organization? >> Jordan Hanssen: No. Not at all. >>: Do you take volunteers? >> Jordan Hanssen: Absolutely [laughter]. >>: Do you take kid volunteers? >> Jordan Hanssen: Yeah. The way it works for the most part is, I mean it takes, it took 18 months with four guys pretty much just doing this, but we didn't know what we're doing, but it still it took 18 months for four guys that all lived in the same house. And then the second trip took four years to get ready because it was four guys that were spread out over the West Coast and so we would meet up online and this stuff was, you know, we'd create these events and all four of us would come together just for some really quick 36 or 48 hours and it was -- what we're working on now is grant funding so we can have a consistent funding to make this something that can happen on a more consistent basis, so we can do it better. But yeah, we are always looking for volunteers. There's just a need for it and it expands and contracts depending on what we're looking for at the time. >>: Because I could see kids getting super excited. >> Jordan Hanssen: Oh yeah. >>: It's like just an amazing thing, and that's what you're finding, right? You are going to the schools? >> Jordan Hanssen: Oh yeah, Uh-huh. >>: What was the final cost of the rescue? >> Jordan Hanssen: The final cost of the rescue was, so the Heijin’s fuel cost $10,000 and we paid for that. We paid for the two flights which were $14,000 each. The tugboat we got basically 50 percent off but that was still $10,000 a day and that was something that the Canadian Wildlife Federation generously paid for. Than the Coast Guard stuff was, you know, that was, that basically cost about $10,000 an hour to run those, and the way they explained to me was that every quarter they have a budget and either they use it saving people or training to save people, so it was -- when I went and actually spoke to these guys right here, they did a presentation and a, it was so easy to find us because we had these PLBs. They just kind of turned it into a training mission and started -- they didn't have to drop all of that stuff on us, but they were kind of required to at some point and they figured, well why not now? >>: [indiscernible] [laughter] >> Jordan Hanssen: Yeah, exactly, and I would, it was interesting because we all, every single coast guard person had that, that had read the brief was asked that question and that's something that at least when I talked to Petty Officer Harper he was saying that he would pass that up the chain of command and it would be interesting to try to track that down but navigating that bureaucracy was pretty tough and even, you'd think that you'd be able to go like say thank you to the guys that saved you and you would think that would be a pretty easy thing. The people who made the beacon, ASR, were just fantastic because they navigated all this bureaucracy. I couldn't have been able to call up someone and get on the base without her doing all of the work before hand which was really cool. >>: Did any of you guys have ocean going experience before this? >> Jordan Hanssen: No. >>: Wow. How did you make your selection of equipment, electronics and so forth? Were there consultants? >> Jordan Hanssen: Oh yeah. So we went, people who helped us out on both trips, but in terms of equipment, the people that took us under their wing were Emerald Harbor Marine out of Elliott Bay and Larry, a guy named Larry and a guy named Dan, they came out and they looked at this boat the first time they saw it and Larry turns to Dan and he says if we don't help these guys they're going to die. [laughter]. We just had all of these people take us under their wing and make sure that we had the best equipment and knew how to use it and we did training rows before. We'd start small and row to Bainbridge and let's go a little bit bigger. Let's row around the islands. Let's take it out on the Pacific and so we made it our business to really be in the boat as much as possible before we got to New York, but at that point we had pretty much spent three or four 24-hour periods at sea and then probably about maybe 12 days total on the boat, and out of that, 18 about 18 months. But I mean, a huge part of this you would think that you'd have time to row across the ocean. You're going to get in really good shape and that's not necessarily the case because we did everything. We had no idea how to make a nonprofit, so we had to beat our heads against the wall for that. Marine electronics, fiberglass, putting on events to raise money, sponsorships, the website, that was stuff we had no experience doing and I wouldn't really say that we are that good at it right now, but we are pretty hardheaded. >>: I have a question from online. How would you change the boating procedures to avoid capsizing again in the future? >> Jordan Hanssen: I think that, I think that the capsizing, I think that danger is always going to be there, but what I think you can do is we could probably put some like lead along the keel or we could take, so we have a dagger board that pokes down and like if you take a 10 pound weight you can hold it here for a really long time, but you can't hold it like out this far for too long. So the dagger board asked like that and so it's sticking down through the deck through the bottom of the boat and I think if you had something like that it would make it a lot more stable down there, but I think what you -- I mean it's the ocean. It's going to flip the 30 foot boat if it wants to flip a 30 foot boat. That's just the reality of it. But one thing you can do is create a bladder that we could keep on deck, put inside and if we flipped put that inside, blow it up to flush the water out of the cabin so that it would regain its self righting capability. At that point your electronics are going to be trashed, regardless. I mean you can only make them so tough, so just have a dry bag that has, you know, a few backup GPS, a backup VHF radio and backup like text satellite communicator and then you have like a hand pump water maker and keep all this stuff down there with enough lithium batteries to run them for, you know, two months if you need to and flush everything out, dry it off and keep going. >>: [indiscernible] >> Jordan Hanssen: Oh we had lots of dry bags. >>: But you didn't have a dry bag that was all set to go with the VHF radio? >> Jordan Hanssen: Everything on a 29 foot boat is a compromise and our grab bag had a VHF radio, but what we were discovering was that we were going to leave that VHF radio in that grab bag, but as we were going along we were talking to ships, every single time you would go into use the hardwired VHF radio which was a little bit stronger, could send out a signal a little bit further, you would wake up the guys and your four hour sleep shift in the middle of the night was, I mean that was an issue of safety. It was keeping people as rested as you could, so what we should have done, again hindsight is 2020, we should have had two extra handheld radios and one to never leave the bag but the decision we made at that time with the resources we were left with was to take that out and to keep that in the bow of the boat so that we wouldn't have to wake up the guys, whoever was sleeping when we would talk to ships. >>: Had you tested the self righting capabilities of the boat. >> Jordan Hanssen: We tested it before the New York trip and afterwards as well, so I've seen the boat self right with people in it. >>: So it would have worked if you had been able to close the door? >> Jordan Hanssen: If it had been five seconds later. >>: You're so lucky that the storm just dissipated when it did, though. Even though you said you didn't have time to feel fear. >> Jordan Hanssen: It was one of those things. The weird thing about that day was it wasn't, it was rough, but it wasn't particularly stormy. It got stormy later that evening once we were on the Heijin a lot more lightning came and the lot more wind, so we were lucky that we got out when we did. >>: How did you manage interpersonal dynamics for four big guys on a small boat? >> Jordan Hanssen: I think the, as long as people are working you can't stay mad at them for too long. I mean, you are going to butt heads a little bit, but you get people out there that are very dynamic people who like to talk and you end up just talking things to death and that's one of -- I find a lot of times we would have the same kind of conversation piece would come up and you would have your little videocam that you could complain to and you just, you've got to learn just know when not to say something or just say hey, the fact that you bring this up all the time is making me feel this way the [laughter] and I don't like that and you don't want me to feel that way. The food issue was a really big deal. And that was because we had food on the second trip everybody was really in pretty good spirits all the time. You get tired and you have good days and bad days, but on that other one it was just you get way more volatile when you're like that, but still that's one thing that just makes me so proud of those three guys is that everybody kept it together and I mean, there was only one time when I had to have, when I needed to basically rein in one of them and tell them that he was going to tell it like it was and I said we can't afford that right now. >>: [indiscernible] Snickers. [indiscernible] >> Jordan Hanssen: Yeah, I'd get sponsored by Snickers. >>: What of the food issue, what happened? You guys just needed to eat more? I know you had to make a trade-off with the weight in the boat, but you just sort of, what happened there exactly? >> Jordan Hanssen: When you look at how a mistake is made, it's not like oh all of a sudden. There's a mistake. There's a bunch of very, a lot of mistakes along the way. Packing the food for a trip like this is a huge job. Anybody who's just packed food for four people for a long weekend, it's way more of a job than you think it's going to be especially if you haven't done it before. So when your food has to have the requirement of weight and it has to last and you have to have enough to feed people that are working out 12 hours a day and not sleeping, it starts to get a lot more complicated and 55 days worth of food at 5000 calories per rower per day looks a lot like 100 if you have no experience with it before. It's not like it's tough math, but you've got to be really precise with it. >>: So eating the fly fish, I mean [indiscernible] >> Jordan Hanssen: It was weird. On the second row, all the guys knew about that and so we did the food really, really well. We made sure that everything was double checked. We made sure we talked nutritionists and we got really, really great food, but I still had this mentality that I would purposely eat less the whole time and the other guys would make fun of me [laughter]. You don't have to worry about that out here, but it was kind of a hard thing when you haven't had enough food for a while and that's really the only option. >>: So eating the fish was good, right? >> Jordan Hanssen: Oh, totally. >>: That's what you are saying, right? You would eat that, because that was protein. >> Jordan Hanssen: Oh yeah, absolutely. >>: How did you deal with boredom? >> Jordan Hanssen: You are always rowing, so you would listen to music; you'd talk to people, but I think it helps to get people on board that like to row, so for the most part you just kind of do that. You sing songs. I mean the ocean is a really dynamic place. You get all the same ingredients, but every single hour the percentage of what's around changes a little bit and you just kind of get into this zone. You have books to read and then I mean you've got to cook. You've got to run the science equipment, write e-mails, write letters back home and I mean, you do that and your days, I mean you know what you are doing down to 5 to 15 minute increments every single part of the day, so you don't really have a lot of time to kind of wander. >>: So it was either stormy or you were rowing? There was no time for you guys to just be hanging out wherever the current would take you? >> Jordan Hanssen: No. We always kept it going. It was kind of nice in this last trip. I hated being on sea anchor just because it just stressed me out. You're not going anywhere; sometimes you're going backwards, but I started to really appreciate it for the amount of -especially when you had enough to eat and you get on deck and you drink some coffee, you could really just appreciate the time, the nearest time you had to sleep and kind of regenerate your body. So after two days on sea anchor your body was feeling really good and you are really eager to get on the oars and you just had more energy. >>: So the boat’s over in Ballard? Are you kind of keeping a permanent or kind of ongoing presence with that or are you using that? >> Jordan Hanssen: Yeah. Right now, it took a few hits to pick it up out of the water to get it on the tugboat and all of the electronics are trashed, so it's going to be a lot of fundraising to get ready for the next trip, so right now we're going to focus on creating this consistent trip down the Mississippi. It's going to happen on a yearly basis to be able to leverage something a lot bigger in which we'll need to get that boat back into top condition again, but right now it's basically stabilized and it's going -- actually tomorrow I am going to take it down to the Foss Seaport Maritime Museum down in Tacoma and it'll be down there. >>: Oh, okay [indiscernible] >> Jordan Hanssen: You know Foss Seaport all the way down there on the Foss waterway? It will be right there, right there for probably at least the next 6 to 10 months. >>: Okay. And then are you going to do [indiscernible] from map locations? >> Jordan Hanssen: Some of it, yeah. Some of it'll be down there. It just kind of depends. I'm doing a talk there tomorrow, but it all kind of depends on where they pop up. Anything else? >>: So you won't be doing much rowing then, will you? It would just go down the Mississippi and go whee. >> Jordan Hanssen: That's true. [laughter] >>: Thank you. >> Jordan Hanssen: You're welcome. [applause]