Running Head: Title: Author: Affiliation:

Running Head: Group-based Mobile Messaging

Title: Group-Based Mobile Messaging in Support of the Social Side of Leisure

Author: Scott Counts

Affiliation: Microsoft Research

Contact:

Scott Counts

Microsoft Research

One Microsoft Way, Redmond, WA 98052, USA

+1 425-722-5057 counts@microsoft.com research.microsoft.com/~counts

1

ABSTRACT

Communication on mobile devices plays an important role in people’s use of technology for leisure, but to date this communication has largely been one-to-one. Mobile internet connectivity can support a variety of group-based messaging and media sharing scenarios. Switching to group-based messaging should enhance the social and leisure aspects of the communication, but in what ways and to what extent? An experimental system for text and photo messaging on mobile devices was tested in a research deployment to four groups of 6-8 participants who used both a group-based and one-to-one version of the system. Results highlight a significant increase in message sending, in mobile device “fun”, and in the social qualities of mobile communication when messaging group-wide, along with a few minor costs. Qualitative feedback provides further explanation of the social benefits.

KEYWORDS

Mobile, leisure, social, social computing, groups, messaging, photos

1. INTRODUCTION

Mobile device-based communication is evolving rapidly, expanding from voice and text, to include photo sharing and, as internet connectivity on mobile devices proliferates, other communication media such as instant messaging. How can we take advantage of these new social communication and sharing capabilities in support of computer-mediated leisure activities?

One potential growth area is group-based mobile messaging and photo sharing. Group-based interactions have long been used in web and desktop environments to facilitate organization and planning, media sharing, topical discussion, and computer-mediated socializing to name a few uses. For the most part, these social benefits have not been translated to mobile devices, possibly because such devices historically were designed for voice communication, which does not scale well beyond the dyad (for a notable exception, see Aoki et al. 2003). Mobile devices are, however, in many ways well suited to group-based communication, especially within a leisure context. For instance, mobile devices often are the primary communication tool for coordinating the face-to-face activities that constitute a substantial portion of our social lives. These tend to involve last-minute coordination with a loosely organized group of friends or family, and the dynamic nature of these social events makes the continual connection mobile devices offer a practical convenience if not a near necessity. Indeed, if we look at teen use of mobile devices as harbingers of the future of mobile communications, we see a highly dynamic, continually updating social organization process (Ito 2005).

This type of messaging to coordinate meeting face to face highlights the role of mobile messaging in support of leisure.

Mobile messaging is also used directly for leisure purposes, such as messaging to pass the time while on a train, and thus for

2

the purposes of this paper, the “social side of leisure” will be defined as social interaction involving communication between two or more people directly for or as a facilitator of leisure. A terrific example of a more directly leisure oriented use of mobile messaging is to share experiences with a person not physically present. Such sharing often goes beyond text to include photos, and camera phones are becoming respectable tools for just this type of experience sharing. Without a doubt, meaningful experience sharing between two people will always be a desirable interaction mode, but extending mobile photo sharing to group-based sharing with family or friends should provide an immediate expansion of the scope of this form of a directly social leisure activity. In fact, widespread group-based text and photo messaging on mobile devices may be a significant step toward “continuous presence”, frequently mentioned as the logical conclusion for social interactions on mobile devices (Vaananen 2002).

Whether through social communication as an end or as a means, leisure activities that are social in nature, ultimately and perhaps most importantly, are about establishing and maintaining the emotional connection between people. Thinking about the interplay between emotional connections and social groups, the social psychology literature shows that cohesive groups encourage cooperation (Turner, 1980), that in turn leads to positive feelings among group members (Sherif, 1966). In the context of computer mediated communication, desktop-based systems supporting passive social awareness among groups have been shown to support coordination among co-workers (e.g., Dourish and Bellotti, 1992). Systems that support groupwide communication and social awareness on mobile devices should provide similar benefits: by expanding the social reach of communication and awareness among group members, group-based messaging on mobile devices should increase group cohesion and subsequently better enable users to meet a fundamental social goal of enhanced emotional connection to their social network. Such systems should also be more heavily used and should be more fun. The primary goal of the research presented here is to systematically assess the degree to which group-based messaging on mobile devices facilitates social communication and the resulting impact on social relationships amongst group members using group-based messaging as a means of direct and indirect leisure.

To test for these effects, an experimental messaging system called Slam was developed for the Windows Smartphone. This system allowed users to create social groups with just a few clicks of the device’s thumb control for text and photo messaging. In addition to group-wide distribution of text and photo messages, the system provided a number of benefits beyond today’s commercially available offerings, including group membership control from the device, group persistence for reviewing content historically, group member profiles, viewable and editable from the device, and simple social event scheduling.

3

This paper presents this system, then focuses on an experimental field study of 4 groups of 6 – 8 friends, family, and coworkers who used the system, and for comparison, an identical system limited to one-to-one messaging, over a 2 – 3 week period.

1.1 Mobile Messaging

Text messaging (texting) is a significant form of communication worldwide, particularly among younger generations, used largely for leisure purposes such as chatting (Grinter and Eldridge 2003). Among other uses, studies highlight the role of texting in “microcoordination” (Ling and Yttri 2002) and for creating a critical private connection for teens wishing to keep communications out of earshot of parents (Grinter and Eldridge 2001), particularly in cultures where teens have relatively little private physical space (Ito 2005). Preferable payment plans in many parts of the world also contribute to the significant use of texting.

In thinking about group-based messaging, it is worthwhile to consider some of the different purposes for which text messaging is used today. Grinter and Eldridge (2001) identified three broad categories of uses for text messages, all of which play a role in day-to-day leisure activities: chatting, communication coordinations, and planning activities. How would these uses be impacted within the social context of a group? Because group-based messaging expands the reach of the conversation, we expect that the amount of chatting would increase simply because conversations in the presence of a group are read and may be expanded on by any member of the group. Communication coordinations (i.e., planning a future communication) are likely more suited to a one-to-one communication context and thus would drop off in a group messaging environment. Messages for planning and coordinating are likely to increase as a direct reflection of increased social communication and awareness. For example, just knowing that someone is free on a Friday night increases the likelihood that others will include her in an outing or get together of some kind and the corresponding pre-event coordination.

How would the more intimate mobile messaging practices, such as gift giving (Taylor and Harper 2002) and teasing

(Kurvinen 2003) fare in the group context? We might expect intimate exchanges to drop off given the somewhat less appropriate communication context of the group. Additionally, there might be less obligation of reciprocity in a group context when messages are not addressed to a specific individual, contributing to a case of diffusion of responsibility (Darley and Latane 1968). Regarding teasing, the group context may better lend itself to a related form of communication: joking. In their frequency analysis of text message types, Grinter and Eldridge coded a fairly small percentage of messages as jokes

(joking was part of an “Other” category totaling only 12% of all messages). This percentage may increase in a group-based messaging environment as group members riff off one another.

4

Finally, how will the group context change the way mobile messaging is used to transition to face-to-face interactions? The increase in social communication might yield more face-to-face interactions. Group members who previously didn’t know each other as well, may feel more comfortable suggesting face-to-face get-togethers, or group members may realize through the messaging that they are physically close enough to one another that a spontaneous face-to-face meeting makes sense.

1.2 Mobile Photo Sharing

Photo sharing also plays an important role in the social side of leisure activities. It is a well documented medium for communicating experiences (Frohlich et al. 2002), and camera phones service such social goals as maintaining relationships and preserving group memory (Van House et al. 2005). Kindberg et al. (2005) stress the importance of common ground in these processes: because image sharing often includes few words, common ground between sender and receiver is critical for understanding the meaning of the media message. Given the additional recipients in group-based messaging, initially some group members might feel left out when they don’t understand the meaning of certain messages. However, the focus on images of everyday life we tend to see in photos from mobile devices (Makela at al. 2000) should help establish common ground. As common ground is established in group-wide messaging, or is already established in an existing social group, its effects reach multiple people simultaneously. Thus, one prediction for group-based mobile media sharing, particularly for known social groups, is an overall strengthening of the social bonds between group members.

Work on camera phone photo usage (Van House et al. 2005) and sharing (Davis et al. 2005; Counts and Fellheimer 2004;

Markopoulos et al. 2004), suggests that it is not only an important medium for social connection, self-expression, and experience documentation, but that usage increases dramatically when barriers to sharing are reduced. Sharing camera phone photos with a group as easily as with an individual marks a dramatic reduction of the barriers to sharing, and we would thus expect a corresponding enhancement to social connections. The experimental system presented here enables users to share camera phone images with social groups simply by taking a photo during composition of a message. Along these lines, the

MobShare system (Rantanen et al. 2004) supports group-wide sharing of camera phone photos with reduced barriers to sharing, although changes to photo sharing behavior and social interactions due to the group context are not reported in their work.

1.3 Mobile Group-Based Communication

The commercial system UPOC (www.upoc.com) that supports group-wide text messaging reports usage numbers that underscore the potential for group-based messaging systems: UPOC reports accounting for 4% of all text messaging traffic in the United States (www.upocnetworks.com/about-us.html). UPOC, however, only provides support for basic group-based

5

text messaging. One research system that certainly goes beyond basic text messaging is The Mad Hatter’s Cocktail Party

(Aoki et al., 2003). Designed for an era of near continual presence, this system targets the audio component of group-based mobile communication by simulating the natural “cocktail party effect” whereby people attend to a conversation among a smaller group in the midst of a larger social context. In a group conversation on mobile devices, The Mad Hatter’s Cocktail

Party system automatically detects who people are talking to and attenuates the volume on the remaining conversation members. Although the Slam system described here is focused on text and photo communications, it is analogous in the attempt to build into mobile devices support for naturally occurring social processes, with The Mad Hatter’s Cocktail Party mimicking natural group conversation dynamics and the Slam system mimicking group membership dynamics (see Slam

User Experience below).

Beyond UPOC the few commercially available options for group messaging generally are limited to adding multiple recipients to email or text messages. This presents a variety of issues, such as lack of user interface for group management and time consuming nature of typing in multiple recipients to an email from a mobile device, that hinder research on this form of mobile device-based computer mediated communication. Many of these issues were addressed nicely in the

QuickML system (Masui and Takabayashi, 2003) that supported the creation of distribution lists simply by sending an email to the system. Once distribution lists are created, distribution list members can be added by sending mail to the list and putting new members on the Cc line. Although not exclusively designed for mobile devices, approximately 45% of QuickML usage is from mobile devices, highlighting the benefit of simple group management, persisted conversation groups, and wider distribution of content to the mobile device user. Similarly the system presented here supports simple group creation and distribution list-like messaging, although rather than email, the Slam system uses either HTTP for internet connected devices and SMS for all other devices. As described in further detail below, the Slam system also provides a rich user interface and additional features such as personal profiles.

2. SLAM

Group-based mobile messaging, then, should support the social side of leisure by increasing communication between group members, particularly around daily life and day-to-day activities. In turn, this should strengthen social relationships amongst group members. To test for these effects, an experimental system for group-based text and photo messaging was developed for the Windows Smartphone. Figure 1 shows the Slam application home screen. The four photo tiles at the top left serve as entry points to the text and photo-based conversation for the four most recently active groups. These photo tiles also show the most recently shared photo for these groups in order to give a sense of recent member activity at the top level of the

6

application. Clicking “All Slams” opens a list of all groups of which the user is a member. The conversation section of the main screen shows unread messages. Clicking a message opens the full message, at which point the user can navigate to the conversation for that group. Clicking the “Conversation” header bar opens an inbox of all messages across all groups.

Finally, the “Jams” section of the main screen shows upcoming events.

The group conversation screen (Figure 2), is a reverse chronological list of messages shared amongst the group. This was modeled after the typical SMS inbox in an attempt to maintain simplicity. However, in addition to text messages, shared photos and group membership changes are also reported as part of the conversation. From this screen, the user can send a new message or photo to the group, can view messages or photos full screen, can remove one’s self from the group, and can invite new members to the group.

To create a new group, the user opens the new group screen (Figure 3) by selecting ‘New Slam’ from the main menu on the

Slam home screen, gives the group a name, and then adds members either from existing groups or from the device’s contact

Figure 2: Group conversation screen

Figure 1: Application home screen list before clicking ‘Create’. Invited individuals will receive the invite in their Slam inbox. This process is particularly quick when selecting invitees from previously existing Slam groups, as entire groups can be selected in a single thumb click, followed by minor modifications to the final list of invitees.

7

Figure 3: Make new Slam group screen

Figure 4: Compose message screen

To send a message, the user opens the compose message screen (Figure 4) by selecting “New Message” either from the application home screen or from the group conversation screen. After keying in the message, clicking “Send” sends the message to all members of the group. Photos are also sent through the compose message screen. The user adds optional text, then either attaches a photo from the device’s storage or takes a photo that will then automatically get attached to the message.

Secondary functionality includes the following:

User Profiles: All users have a profile, with modifiable ‘About Me’ statement and photo. When viewing a profile, users see the intersection of content between themselves and that other user, such as groups and events in common.

Events: Users can send events to Slam groups. The event system in Slam is fairly simple, targeting everyday usage scenarios, such as a Friday night movie, rather than larger, more formal events. Event messages contain descriptive text along with a date and time, and are displayed on the application home screen until the event has passed.

SMS backwards compatibility: The Slam system can send and receive SMS text messages, so non-Smartphone users can participate at least in the group-based text messaging.

Home screen plugin: The arrival of new Slam content is communicated to the user through a plugin for the

Smartphone home screen that reports the number of new messages. While not novel from the user perspective, this is critical functionality for engaging the user with Slam content.

8

2.1 Slam User Experience

Broadly, Slam was designed to support messaging between two types of groups: long-standing groups, such as close friends, and temporary groups, such as business travelers coordinating a dinner. Messaging among long-standing groups, which might include family and co-worker groups, is a dominant scenario and is the focus of the experimental field study described below.

Even amongst long-standing social groups, a substantial percentage of social interactions involve similar, but different, groups of people: the group of friends a person had dinner with Friday night might have partial, but not total, overlap with the group she went to a movie with Saturday night. A major design goal was to mimic this natural and fluid social grouping process we experience in our real world social lives. Stepping through an example of this dynamic grouping process, the user would begin by creating a new Slam group, likely starting with an existing group and making necessary modifications to the group membership (see Figure 3). Once the new group is created, all messages and pictures shared are distributed groupwide. This group continues to exist in the system so members can view pictures later or leverage this group as a starting point for a new Slam group.

Slam groups are prioritized by recency of activity in the user interface. Thus if a group created for coordinating a big weekend party turns out to have no additional interaction, it simply fades into a history of temporary groups. On the other hand, if the group continues to communicate and interact, beginning to move toward becoming a long-term social group, the group bubbles to the top level of the Slam user interface. Should this group grow into a standing friends group, its membership is likely to evolve through a natural social networking process. For example, the group from the big weekend party might turn into a group of friends who like to go dancing. As group members meet new people or see old friends that also enjoy dancing, they can add these new people to the group. At some point, a subset of members might want to splinter off into their own group. Again, the goal was that the system, and the user interface, supports these naturally occurring social group dynamics.

2.2 Technical Description

Slam was implemented using a client-server architecture (Figure 5). The backend consists of a SQL database, web service, and additional software for integrating a set of phones capable of sending and receiving SMS messages. Any client type can interface with the web service using the HTTP protocol. In our case, the primary client is the dedicated Smartphone application, with client-server communication routed through a standard mobile operator internet connection. The SMS interface required the additional step of connecting each send/receive phone to a computer that handled message queuing and communication with the web service.

9

Figure 5: Slam system architecture schematic

In terms of data flow, any data transferred from a Smartphone client, say an acceptance of invitation to join a group, would be sent immediately to the server, which would store the content in the database along with any relevant organizational information (group membership changes) and metadata (system usage timestamps). Relevant outbound data, such as notification of the new member joining the group, is then routed to the appropriate message queue for distribution. If the recipient is an SMS user, the outbound message is sent immediately once it gets to the front of the SMS outgoing message queue. Due to battery drainage issues, the Smartphone clients check the web service for new data every 10 minutes. If there are new data, or if the user has sent a message, the Smartphone clients checks for new content every 30 seconds until there is no activity, at which point it returns to a 10 minute data check cycle. Smartphone users can initiate a send/receive if desired.

Once the new data arrives, the Smartphone client integrates it into a local store for faster display in the user interface and offline usage.

3. EXPERIMENTAL FIELD STUDY

An experimental field study was conducted with Slam to assess the potential social benefits of group-based mobile messaging. Groups of participants used the Slam prototype as described above for group-wide messaging as well as a slightly modified version of Slam that permitted only one-to-one messaging. Groups used each version of Slam for 7 - 10 days. Usage behavior was logged and participants completed questionnaires throughout the study, as well as provided qualitative feedback in a round-table wrap-up discussion. In addition to the impact of group-based messaging on social connections, secondary questions targeted the role of different usage modalities (e.g., coordination, social sharing).

10

3.1 Method

3.1.1 Participants

Participants were four groups of 6 - 8 friends, with some groups including siblings and co-workers. A total of 29 people participated, with group sizes of 8, 8, 7, and 6 people, respectively. Participants were given software gratuities in exchange for participation. Study groups were required to be existing social groups whose members communicate at least once per week and have a demonstrated desire to communicate with one another. All participants were required to have mobile phones with SIM cards. Participant ages ranged from 19 to 28, with a mean age of 24. Gender broke down to 9 females and 20 males, which was more skewed toward males than desired, but simply the result of the friends groups that were available and met the recruiting criteria. 17 participants were white, 9 Asian-American, and 3 Hispanic.

The groups were quite different in their social makeup. The first group consisted of highly social urbanites, who see one another “every day” and tend to go out on the town nearly every night of the week. They were also extremely savvy of social and mobile device technologies. The second group was also quite technologically savvy, but knew one another through church and were considerably less inclined to go out to bars and dance clubs. Members of this group reported being close, but not as close to one another as the first group. The third group differed in that they were slightly older, more professional, and less familiar with mobile and social technologies. Although they tended to own the latest “cool” mobile phone, it was used more for business and less for social messaging. Four members of this group worked in the same office, so they spent long blocks of time co-located during the work week. The fourth group was distinct in that they were geographically separated, with members living in three different cities, each several hours drive away from one another.

All participants were provided iMate Sp3 Smartphones with Slam installed. Participants used the SIM card from their personal mobile phones in order to maintain their phone number and contact list throughout the study. All participants signed up for unlimited data access for their mobile accounts, which was reimbursed by the experimenters.

3.1.2 Procedure

Participants met with the experimenter twice, once at the start and once at the conclusion of the study. During the first meeting, participants were introduced to the Slam software and given a hardware overview to ensure all participants had working internet and phone connections on the devices given to them for the duration of the study. During the wrap-up session, participants shared their experiences with the experimenter through a set of targeted round-table discussion questions.

11

Throughout the approximately 15 - 20 days of each group’s study session, participants used both the group-based and one-toone messaging versions of Slam, each for half of the total time. Differences in the total time for each group were due to issues with scheduling all members of the groups to meet for the introductory and wrap-up sessions. The order for which messaging condition participants experienced first was counterbalanced across the groups in order to evenly distribute any novelty or other order effects. The number of weekends also was distributed evenly across the messaging conditions.

Questionnaire feedback was solicited immediately following each messaging condition. That is, at the midpoint of the study, participants were sent email asking them to complete a questionnaire regarding their social experiences with whichever version of Slam they had just completed. They then switched to the other version of the software, and completed the questionnaire on use of that version at the end of the study.

3.1.3 Data

Data collected were of three types: system usage data, questionnaire responses, and round-table discussion feedback. Usage data were used to assess the quantity of social interactions as measured by the number of messages sent. All messages were also coded for message type to get a sense of how the two messaging conditions impacted the ways in which participants communicated using the software. The questionnaires were used to gather participant’s subjective sense of the impact each messaging modality had on their social relationships with other group members. Finally, the round-table discussions were used to capture qualitative feedback on participant’s experiences with both versions of the system.

3.2 Results

3.2.1 Usage Data

12

3

2.5

2

1.5

1

0.5

0

5

4.5

4

3.5

Group

One

All Text Photo

Figure 6: Participants sent more messages when communicating group-wide

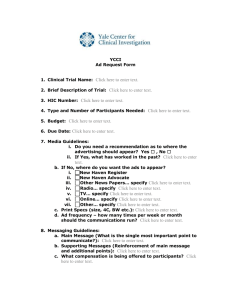

Usage logs were analyzed for the number of messages sent in each messaging condition. Initial scans of the logs showed a bit of a novelty effect where participants used the system heavily the first day or two. Although the order of the two messaging conditions was counterbalanced across groups, to better assess more standard usage, the first day’s usage was dropped from each group for this analysis. Given minor logistical issues, not all participants used each messaging modality exactly the same length of time. Usage results presented here are thus messages sent per day rather than an overall total. Unfortunately, 5 participants experienced technical difficulties that forced them to miss a substantial portion of one of the messaging conditions and were consequently dropped from the quantitative analyses. All statistical comparisons were evaluated with 2tailed within subject t-tests.

Participants sent significantly more total messages in the group-based messaging condition (M

G

= 3.93 per person, per day) than in the one-to-one messaging condition (M

O

= 1.83; p < .05). Total messages does include some group-only message types such as invitation and join messages for newly created groups. However, participants also sent more text only (M

G

=

2.93, M

O

= 1.39, p < .05) and photo messages (M

G

= .78, M

O

= .40, p < .05) each day when communicating group-wide

(Figure 6).

As mentioned, all messages were coded for message type. The message types were chosen based on an initial analysis of messages in the system, as well as from previous coding schemes of text messages in the literature (Grinter and Eldridge

2001). Messages were coded into one of seven types: chatting, coordination, microcoordination, joking, experience sharing, intimate, and photo sharing. Worth noting is that each of these message types is leisure related, with each reflecting a unique aspect of leisure within a social context. An experimenter and an outside party coded the more than 1400 messages for message type, with disagreements discussed and resolved to produce a final coding.

13

The following criteria were used to distinguish the message types. Coordination messages contained specific dates, times, or plans (e.g., “are we all doing something tomorrow night with ty?”), while microcoordation messages reflected obvious midcoordination text (e.g., “I’m on my way”). Slam event messages were counted as coordination messages. Experience sharing messages (“I just ate a chicken ceasar salad and [name] got into a bar fight”) made a statement about a current experience that was either detailed or emotionally meaningful, or both. This distinguished them from status messages (e.g., “I’m at work”), which were often a response to a greeting message, such as “what’s up?”. Status and greeting messages were both lumped into the chatting category.

Photo sharing messages were messages that either contained only a photo and no text or text that obviously referred to the photo, such that the focus of the message was on sharing the photo (e.g., “this is my favorite thing in belltown. it’s a hand.”).

Thus, many messages other than those coded as “photo sharing” contained photos. Intimate messages contained text that conveyed affection for the recipients, such as the “goodnight” message (Grinter and Eldridge 2001). Finally, joking messages were often hard to distinguish, as much of mobile messaging involves kidding and light ribbing. A joking message had to be a clear joke or contain words such as “ha ha” that indicated a joke was being made. All remaining messages were coded as chatting.

Figure 7 shows the message type breakdown for the two messaging conditions, with percentages relative to the total number for each messaging condition. The two were quite similar in terms of relative percentage, although keep in mind that in terms of absolute numbers there were more than twice as many messages sent in the group message condition. In both cases, chatting, arguably the most directly leisure activity, was the dominate usage. Group messaging did yield 10% less chatting, although half the difference was made up in the joking category, which previously had (Grinter and Eldridge 2001) been classified as a sub-category beneath general chatting. A slight increase in experience sharing in the group condition also contributed to the difference in general chatting.

14

In terms of planning, the amount of coordinating was identical in each messaging condition, although three times as much

Group Messaging

Intimate

2%

Exp. Sharing

11%

Joking

9%

Coordinating

18%

Photo

Sharing

9%

Microcoordi nating

3%

Chatting

48%

One-to-One Messaging

Intimate

3%

Exp. Sharing

8%

Joking

4%

Coordinating

18%

Photo

Sharing

8%

Microcoordi nating

1%

Chatting

58%

Figure 7: Breakdown of message types for group-based (above) and one-to-one messaging microcoordination took place in the group condition. The absolute amount of microcoordination was small, however. The percentage of photo sharing and intimate messages was roughly the same.

Looking at system uses other than messaging, first, an average of 3.75 subgroups were created per study group over the course of the group messaging period. Second, participants created very few Slam events in either messaging condition (M

G

= .06 events per person per day, M

O

= .04, ns.).

3.2.2 Questionnaire Responses

Upon completion of each messaging condition, participants completed a questionnaire regarding their social interactions with the other members of the study group. Questionnaire items were similar to those used in previous work (Counts and

Fellheimer 2004; Markopoulos et al. 2004), with key concepts including sense of connectedness and ability to share experiences. Table 1 shows all items, as well as mean responses for messaging condition and p-values reflecting significant

Item Group One Sig.

Easy to Communicate w/Others

Feel Connected to Others

Up to Date in Other’s Lives

Satisfied with Friendships

6.1

5.7

5.4

5.6

5.1 <.05

4.6 <.05

4.6 =.09

5.2 =.07

Group is Cohesive

Am Member of Community

Share My Experiences

Mobile Communication is Fun

5.3

5.5

5.5

6.0

4.1

4.4

4.4

4.1

Table 1: Mean questionnaire responses

<.05

<.05

<.05

<.05

15

improvements when messaging group-wide in most cases. Demonstrating the connection between social goals and the more playful side of leisure, participants reported communicating with their phones to be significantly more fun in the group condition. All items were 7-point Likert scale questions, and statistical comparisons made with standard 2-tailed within subjects t-tests 1 .

The questionnaire also asked for self-reports on how often participants saw one, and two or more, other member(s) of the study group in person, and how easy it was to coordinate face-to-face meetings in both cases. For both meeting one (M

G

=

5.96 self-reported instances, M

O

= 5.70, ns.) and two or more other group members (M

G

= 5.09, M

O

= 5.14, ns.), participants reported similar numbers of face-to-face meetings. It was, however, significantly easier to coordinate meeting two or more people when messaging group-wide (M

G

= 6.05, M

O

= 5.24, p <.05).

3.2.3 Qualitative Feedback and Message Content

In addition to the usage and questionnaire scale data, participants provided qualitative feedback both on the questionnaires and in round-table discussion sections at the conclusion of the study. This free-form feedback, along with an examination of message content, was useful for articulating the different ways the group-based messaging impacted participant’s social interactions.

Connecting and Experience Sharing The increased social connection reported in the questionnaire results was echoed strongly in the round-table discussion comments: “We definitely connected in ways we hadn’t before”; “group Slam was really easy to show your friends what you were doing”; “the easy access to sending a message to an entire group definitely enhanced my ability to communicate, made it feel like we were bonding more I guess.”

There were numerous comments on the role of experience sharing. For example, one person sent a message to the whole study group saying, “Yay! I got my apartment” when her application to rent a new apartment was accepted. In terms of receiving messages, one participant remarked, “I loved when I got pictures of my friends doing things throughout their day”, and in terms of sharing one’s own experiences, another reported, “I like being able to let people know what I am doing all the time”. Sometimes, the seemingly mundane was in fact quite meaningful. Several groups reported that even though they were quite close, seeing pictures of one another’s respective places of work opened a window onto a part of their lives they had not seen before.

1 These were also run using the Wilcoxon non-parametric test with no meaningful change to the results.

16

As shown in the message type breakdown (Figure 7), intimate messages, while constituting a small percent of the total messages, were sent out to groups. The “goodnight” message was sent around several times, as when one person sent a picture of his alarm clock reading 12:30 along with a good night message. Good morning messages were also seen, as were messages of general affection such as “I miss u guys!”, and emotional connection, like, “I’m totally in need of some praise and encouragement!”, and, “it's great to feel so CONNECTED guys! love you mean it. G'night!”

Although not common, there were instances of using the system for more functional sharing, such as sending URLs or phone numbers, or when one person sent out a picture of some shoes she saw on eBay: “who+has a size 8 foot? these heels are TO

DIE FOR- they're covered in SILVER SEQUINS. EBAY. get it.” In the wrap-up discussions, participants reported that they used Slam for these messages because they wanted group members to receive the messages immediately, rather than the next time they checked email.

Impact of Group Membership Like any social group, these mobile device-based groups have memberships with both positive and negative implications. Some of these implications are exacerbated because of the ubiquity and visibility of the mobile device. In several cases, for example, participants noticed a group that they did not belong to when they were co-located with another participant who had their phone out. “Why aren’t I in the Paris Hilton group!” exclaimed one participant, whose invitation to join the “Paris Hilton” group had been overlooked. In another example, one woman in the third group was the boyfriend of one of the men, and consequently had frequent access to his mobile phone. Because she could read the messages in the “boy talk” group by simply picking up her boyfriend’s phone, she was very aware of a social interaction to which she was not privy. Although “boy talk” was created to “spare” her from the somewhat vulgar exchanges, when the rest of the

“boy talk” members found out she saw their messages, they felt it a violation of an assumed confidence.

In the two groups that were largely men, women reported feeling a bit left out, and even self-conscious, thereby limiting their participation: it was “a little weird and restrictive because I wasn’t one of the boys”. On the other hand, subgroups were also used quite positively to reflect naturally occurring friendship groupings within the larger group. For example, three people in the first study group created a “three amigos” group of just three members who attended high school together, so they could talk about “the good old days”.

In terms of the number of groups participants thought they would have if they used a system similar to Slam regularly, most participants reported 3 – 10 groups, which might include family and work groups. Generally, participants assumed their groups would correspond to the different groups that they “hang out” with. More temporary groupings, such as for coordinating rides and sharing pictures from a party or weekend trip were only hesitantly endorsed.

17

As Entertainment For many people, group-based messaging on their mobile devices was an almost addictive new form of entertainment: “I didn’t want it to die, so I plugged it in at work… I would never SMS at work”. A number of participants noted in their wrap-up sessions that “it was so entertaining”, and that “[they are] going to miss slam”. Others mentioned how exciting it was to have their phones buzzing with new messages all the time, or how much they liked waking up to new Slam messages. The downside seemed to be that, for some, group interactions on a mobile device were socially overwhelming (“I don’t want to be that connected to my friends all the time.”) or too engrossing. One person commented was that “it kept me from interacting with other friends of mine that weren’t in the study” Another said, “Other friends were asking me how come

I never SMS anymore”.

Often the consumption of message content took on an entertainment quality. In addition to looking forward to the ongoing stream of glimpses into their friend’s lives, each of the four groups reported instances of watching group members trying to outdo one another for the funniest comments or contributing to a running joke. During the wrap up session members of one group noted that “they never knew [name] was so funny.” Based on these observations and as shown in the message type breakdown (Figure 7), it does appear that the group context serves as a catalyst for ribbing and humorous interactions that was part of the ongoing entertainment stream of group-wide messages. In a similar, but less humor related vein, there were several instances of users “publishing” a travelogue of a day or weekend trip.

4. Discussion

The increase in messages sent indicates that participants were either motivated to send more messages by the wider audience or replied to messages of interest they simply would not have seen if messaging one-to-one. In either case, this increase generated a corresponding increase in most of the social relationship metrics collected in the questionnaires: participants felt more connected, more like a member of a community, and that they shared more of their experiences. Participants also reported having more fun. The increase in system usage and corresponding increase in social relationship metrics indicates that, as a system supporting leisure, group-based mobile messaging played a larger role in participants’ social lives than did one-to-one messaging. Revisiting the impact on social psychological factors, participants did report greater cohesiveness in the group messaging condition. It was predicted that this would generate greater emotional connection, which was validated by the reported increase in connectedness among group members.

These increases suggest corresponding increases in additional social psychological aspects of group dynamics, such as being more likely to participate in and contribute to group activities (Brawley et al., 1988), the ability to work together toward group goals (Sherif, 1966), and the satisfaction with belonging to the group that derives from increased shared social identity

18

(O’Reilly and Caldwell, 1985). Although such findings are not directly assessable given the current data, there were indications to draw on. For example, the groups were inclusive and cohesive regarding group activities and goals. In one group, seven members covertly organized gift buying and party organizing for the eighth person’s birthday, with everybody contributing ideas and each person taking on a different role, such as stopping off to pick up a gift on their way home from work. More systematic study of the effect of group messaging on these additional social psychological aspects of group dynamics poses an interesting avenue for future efforts.

The social benefits appear to be due to the sheer increase in volume of messages sent in the group messaging condition, as the types of messages sent when messaging group-wide were remarkably similar to those sent one-to-one. Had joking messages be included in the chatting category, the two messaging modes would have broken down nearly identically.

Nonetheless, in both the group and one-to-one communication modalities, the message content reflected the intersection of the leisure and social sides of mobile messaging: simply chatting was the most common activity, but participants also joked, shared experiences, and coordinated face-to-face activities. A more detailed look at how participants used group-based messaging revealed that it quickly became integrated into their lives in terms of time and place. Although evening was a popular time to message, early morning, late night, and daytime work hours were far from infrequent message times, with message content clearly relevant to the time of day, such as the good night message or the photos of workplaces. The messages also reflected the places that make up people’s lives, with text and photo messages covering places such as home, work, and social places. Because the messages were intertwined with other aspects of communication, the glimpses into people’s places often pertained to the everyday, but personal places such as the person’s desk at work or the home computer of the person who sent around the picture of the shoes on eBay. In other words, because the types of messages were so varied and because messages were sent at many times and from and about many places, a substantial amount of social presence was conveyed.

There were a few points worth noting regarding the message types. First, the increase in microcoordination messages in the group condition, while still a small percentage of the total, suggests that group-based messaging might support social coordination in cases where one-to-one messaging falls short simply by being too cumbersome or slow to use at the last minute. Whether the increase in microcoordination messages resulted from greater social awareness and therefore inclusion as proposed earlier is difficult to assess, but it was reflected in the reported greater ease of planning face-to-face meetings afforded by group-based messaging. Although this planning was easier, groups did not report an increase in the actual number of face-to-face encounters. This implies that this social technology does not, or rarely, facilitates serendipitous face-

19

to-face interactions, as these are largely dictated by other means, and instead facilitates the communication involved in coordinating these encounters. Second, that groups engaged in intimate exchanges was somewhat surprising, although the relative percentage of intimate exchanges was somewhat smaller as expected in the group messaging condition. The extent to which this would take place amongst groups likely depends on the makeup of the group. Indeed, the two groups consisting largely of men sent only a couple of intimate messages, whereas the more gender-balanced first group sent almost 20.

Families, and other groups that share the precursors to intimacy (Vetere et al. 2005), such as trust and commitment, might engage in more intimate group-wide messaging. While intimate messages were shared with a group, the round table discussions revealed that the act of sharing alone is often enough to heighten connectedness. More than one group remarked that just getting small glimpses into the “little things” in their friend’s day to day lives that they would not otherwise have seen was meaningful. This type of mundane sharing helps establish or build on existing common ground, and is facilitated by group-wide messaging in that recipients are receiving messages that might otherwise have been sent only to someone else.

That this technology supports physical world social groups impacted how the communication medium was employed. Group and subgroup memberships were fairly discoverable in regular face-to-face contact, and membership and privacy violations appeared to be taken quite personally. This highlights the need for further thinking on membership privacy issues. Important differences from other online group interaction spaces are that mobile device-based groups such as these are small, making lack of participation noticeable, and the members of the group all know one another in their physical world social lives, increasing the comfort level for commenting on other group member’s behavior. In fact, lack of participation was often called out to the whole group by other group members: “[User name] why aren’t you slamming?” To compensate, it is critical that these systems support naturally occurring social group boundaries and their always evolving dynamic nature. New groups need to be easy to make, and systems might leverage naturally occurring physical world social interactions, such as social events, to suggest subgroups to the user. Flexible memberships for ongoing membership modification can also help.

The somewhat controlled nature of the study provided the opportunity to attain critical mass among small, existing social groups along with other benefits to the research process, such as being able to meet face to face with each study group. The downside to this methodology was that the system is somewhat removed from the broader context of users’ full social networks. In fact, this was noted by several participants, such as one person who commented that he would need a much larger portion of his social network in the system, “so [he] could seriously separate the large group into smaller social circles,” in order for it to be really useful. Regarding group memberships and group formation, how might Slam or something similar be used in a less controlled setting with a wider net cast across user’s social networks? Given that even in this limited

20

trial, the naturally occurring subgroups arose quite quickly, such as the group of three friends from high school or the woman somewhat isolated in a group of men who could “easily see a girls group”, we would expect to see many more groups and subgroups in a more comprehensive social context. The ability to make these groups easily should smooth out some of the sensitive social issues surrounding group membership, and issues of exclusion due to the closed nature of the system, such as participants failing to text message with their other friends, presumably would subside in the case of an ubiquitous groupbased messaging system. However, digital communication groups are not likely to be tremendously different from their physical counterparts, complete with their share of membership and status issues. Fleshing out the degree to which these two are similar regarding social status presents a fascinating research opportunity. Although this may be done with web-based groups, like Yahoo! Groups, mobile messaging groups arguably are better digital analogues of the physical group dynamics of interest given their close tie to the physical groups themselves and their focus on communication and experience sharing, which influence group cohesion and other indicators of the health of a social group.

In summary, this paper presented an experimental system for group-wide text and photo messaging. In a user study, system usage revealed that the presence of the group significantly increased the number of messages sent by group members.

Participants used group-based messaging for roughly the same purposes as one-to-one messaging, but the increase in message volume generated improvements in social relationship metrics. Given that the message types all reflect some aspect of the social side of leisure, the group context augmented both participant’s social relationships and their interpersonal leisure activities. This type of group communication is relatively unique in a mobile device context in that it supports small groups of known, and close, friends or family. Results and feedback suggest this meant that group-wide messaging was often personal in nature, and that group memberships were discoverable and meaningful, which also generated some social costs.

Because the system is so closely tied to physical world social groups, it must mirror the dynamic nature of user’s social groups. Despite any relatively minor social costs, group-based mobile messaging shows promise for strengthening social ties and providing an outlet for both digital and physical world leisure that is entertaining and functional.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks to Shelly Farnham and Jordan Schwartz for their work on the Slam project. Also thanks to Henky Alimin for his development work on Slam.

21

REFERENCES

1.

Aoki, P.M., Romaine, M., Szymanski, M.H., Thorton, J.D., Wilson, D., and Woodruff, A. The Mad Hatter’s Cocktail

Party: A Social Mobile Audio Space Supporting Multiple Simultaneous Conversations. In Proc. CHI 2003 , ACM Press

(2003), 425-432.

2.

Brawley, L.R., Carron. A.V., and Widmeyere, W.N. Exploring the relationship between cohesion and group resistance to disruption. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 10 , 199-213.

3.

Counts, S., and Fellheimer, E. Supporting Social Presence Through Lightweight Photo Sharing On and Off The Desktop.

In Proc. CHI 2004 , ACM Press (2004), 599-606.

4.

Darley, J.M., and Latane, B. Bystander Intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8 , 1968, 377-383.

5.

Davis, M, Van House, N., Towle, J., King, S., Ahern, A., Burgener, C., Perkel, D., Finn, M., Viswanathan, V., and

Rothberg, M. MMM2: Mobile Media Metadata for Media Sharing. In Late Breaking Results CHI 2005 , ACM Press

(2005), 1335-1338.

6.

Dourish, P. and Bellotti, V. Awareness and Coordination in Shared Workspaces. In Proc. CSCW 1992 , ACM Press

(1992), 107-114.

7.

Ito, M. (2005): Mobile Phones, Japanese Youth, and the Replacement of Social Contact. In Mobile Communication s: Renegotiation of the Social Sphere , Rich Ling and PerPedersen, Eds.

8.

Frohlich, D., Kuchinsky, A., Pering, C., Don, A., and Ariss, S. Requirements for Photoware. In Proc. CSCW 2002 , ACM

Press (2002).

9.

Grinter, R.E., and Eldridge, M.A. Y do tngrs luv 2 txt msg? In Proc.

7 th European CSCW Conference , (2001).

10.

Grinter, R.E., and Eldridge, M.A. Wan2tlk?: Everyday Text Messaging. In Proc. CHI 2003 , ACM Press (2003), 441-448.

11.

Kindberg, T., Spasojevic, M., Fleck, R., and Sellen, A. I Saw This and Thought of You: Some Social Uses of Camera

Phones. In Late Breaking Results CHI 2005 , ACM Press (2005), 1545-1548.

12.

Kurvinen, E. Only When Miss Universe Snatches Me: Teasing in MMS Messaging. In DPPI 03 , ACM Press (2003), 98-

102.

22

13.

Ling, R., & Yttri, B. (2002). Nobody sits at home and waits for the telephone to ring: Micro and hyper-coordination through the use of the mobile telephone. In J. Katz & M. Aakhus (Eds.), Perpetual contact (pp. 139-69). Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

14.

Makela, A., Giller, V., Tscheligi, M., and Sefelin, R. Joking, storytelling, artsharing, expressing affection: A field trial of how children and their social network communicate with digital images in leisure time. In Proc. CHI 2000 , CHI Letters

2(1).

15.

Markopoulos, P., Romero, N., van Baren J., Ijsselsteijn, W., Ruyter, B., and Farshchian, B. Keeping in Touch with the

Family: Home and Away with the ASTRA Awareness System. In Late Breaking Results CHI 2004 , ACM Press (2004),

1351-1354.

16.

Masui, T. and Takabayashi, S. Instant Group Communication with QuickML. In Proc. of Group 2003 , ACM Press

(2003), 268-273.

17.

Sarvas, R., Viikari, M, Pesonen, J., and Nevanlinna, H. MobShare: Controlled and Immediate Sharing of Mobile Images.

In Proc. of MM 2004 , ACM Press (2004), 724-731.

18.

Sherif, M. (1966). In common predicament: Social Psychology of intergroup conflict and cooperation.

Boston: Houghton

Mifflin.

19.

Taylor, A., and Harper, R. Age-old Practices in the “New World”: A Study of Gift-Giving Between Teenage Mobile

Phone Users. In Proc. CHI 02 , ACM Press (2002), 439-446.

20.

Turner, J.C. (1980). Fairness or discrimination in intergroup behavior? A reply to Braithwaite, Doyle, and Lightbrown.

European Journal of Social Psychology, 10 , 131-147.

21.

UPOC: http://www.upoc.com

22.

UPOC Networks. http://www.upocnetworks.com/about-us.html.

23.

Vaananen, K. The Future of Mobile Communities: Evolution Towards Continuous Presence. In SIGCHI Bulletin ,

May/June, (2002), 9.

24.

Van House, N., Davis, M., et al. The Uses of Personal Networked Digital Imaging: An Empirical Study of Camerphone

Photos and Sharing. In Ext. Abstracts CHI 2005 , ACM Press (2005).

25.

Vetere, F., Gibbs, M., Kjeldskov, J., Howard, S., Mueller, F., Pedell, S., Mecoles, K., and Bunyan, M. Mediating

Intimacy: Designing Technologies to Support Strong-Tie Relationships. In Proc. CHI 2005 , ACM Press (2001), 471-480.

23

24