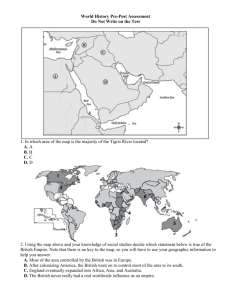

– Part 1: Jerusalem Teaching Geography Workshop 4: North Africa/Southwest Asia

advertisement

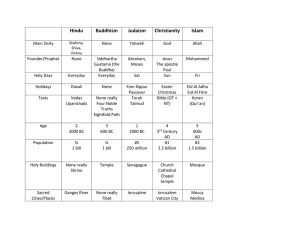

Teaching Geography Workshop 4: North Africa/Southwest Asia – Part 1: Jerusalem JIM BINKO: The region of North Africa/ Southwest Asia is unified by its desert climate and by the dominance of Islam. Such regional unification is exemplified by Geography Standard 5: That people create regions to interpret Earth’s complexity. Remember that regions are human constructs; they are fluid concepts, overlapping and changing over time, often defined by multiple criteria. As you watch the case study, identify the physical and human factors that serve to define the region in question. Our case study is Jerusalem, an ancient city whose history makes it sacred to Muslims, Jews and Christians. It is a holy city whose symbolic meaning and function illustrates Geography Standard 6: How Culture and experience influence people’s perceptions of places and regions. All three religions attach special significance to Jerusalem. Their competition for this sacred space has led to volatile conflict during the past 2,000 years. As you watch the case study, look for ways to explain why places and regions are important to human identity and as symbols for unifying or fragmenting society. The tragic conflict in Jerusalem provides a compelling context for exploring Geography Standard 13: How the forces of cooperation and conflict among people influence the division and control of Earth’s surface. In our classroom segment, ninth-grade teacher Ungennette Brantley Harris helps her students better understand this difficult situation. As they explore the plight of refugees and those living in Israel's occupied territories, they come to see the human face of the Israeli/Palestinian conflict. In doing so, these students gain insight into the complex claims on this region, claims that do not lend themselves to quick and easy resolution. NARRATOR: For half a century, Israelis and Palestinians have battled over Jerusalem and a larger homeland. Helping to mediate competing claims was Dennis B. Ross, Special Envoy for the first President Bush and then President Clinton. As his term ended, the peace process crumbled. DENNIS ROSS: The intifada that began has had lots of casualties. What is so disheartening for someone like me after having devoted so much time to this effort is that in the year 2000, the Palestinians were, in fact, this close to being able to achieve their aspirations. Today the gap between their aspirations and reality is enormous. NARRATOR: Whatever the future, it is rooted in the historical and political geography of the whole region. Here the culture hearth of Muslims, Christians and Jews was controlled first by the Ottoman and then by the British Empire in the first half of the 20th century. These were colonies without firm borders or recent experience with self-rule. At its core, Jerusalem was more a religious than a political center. David the king started the capital here 3,000 years ago. And since then, nobody ever made it a capital. And the Muslims were here for 1,500 years or something of the kind, 1,400 years. (\man speaking Arabic\) TRANSLATOR: This is a very holy place for the Muslims. For centuries it has been the first holy place after Mecca and Medina, the most holy places of the Muslims all around the world. NARRATOR: For Muslims, this is where Abraham offered to sacrifice his son, and Muhammad rose to heaven. \Jerusalem est le centre... TRANSLATOR: Jerusalem is the center and the source of the faith. For the Jews, it's the city of David. For me, it is the city in which Jesus died for us and rose again from the dead. This is the beauty, but also the paradox and sometimes the tragedy of Jerusalem. One city, two people, three religions. It could thus be a wonderful sign of oneness for which the whole world strives, a situation of peace or a sign of opposition. NARRATOR: As a place of religious significance, Jerusalem has few equals. But the conflict here is more about nationalism than religion. The modern story begins with upheaval, not in the Middle East, but in Europe. In the 1930s, a growing number of Zionist Jews immigrated to Palestine in search of a homeland safe from Nazi and other persecutions. They dreamed of a Jewish state. But the Palestinians wanted their own state, too. After World War II, the United Nations proposed dividing Palestine into a Jewish state with slightly more than half the land and a Palestinian state with 45%. Jerusalem and Bethlehem were to have special status under United Nations jurisdiction. In 1948, the pace quickened. At midnight on May 14, the British withdrew, and that was the end of the British mandate. Upon their withdrawal, Israel proclaimed statehood. NARRATOR: The Jews celebrated. But the Arabs were two-thirds of the population and owned more than half the land. They rejected the plan and began fighting. In the war that followed, the Jews prevailed, enlarging their territory, but only able to capture the western half of Jerusalem. They made their first capital in Tel Aviv. Jerusalem became a divided city. The boundary drawn between West and East Jerusalem was called the Green Line, and that's what Highway Number One is still called today. East Jerusalem was then part of Jordan, and it contained the Jews' holiest sites, including their ancient Temple, destroyed by the Romans in the year 70 C.E. MAN: The Western Wall faces the west of the Temple. Once the Temple was destroyed, all that remained was the Western Wall. This place is important for the Jewish people worldwide. ROSS: This is what people prayed to ever since the second Temple was destroyed, ever since the Jewish people were dispersed. NARRATOR: But because it was in Jordanian East Jerusalem, the site was off-limits to Jews until 1967. That year, Israel defeated threatening Arab armies in the Six-Day War, and gained control over more territory. From Syria, they took the Golan Heights. From Egypt, they captured the Sinai Peninsula and the Gaza Strip. From Jordan, they occupied the West Bank of the Jordan River, including the rest of Jerusalem. ROSS: After the Six-Day War, after the victory in '67, with the unification of Jerusalem, one of the very first things done, by a Labor-led government, was to make it clear that Jerusalem would never be divided again. NARRATOR: Israel had moved its capital to Jerusalem in 1950, but now it redrew and expanded the city's boundaries. The areas of Arab and Jewish neighborhoods had been clearly delineated by the Green Line, but in 1967, Israel began building Jewish settlements in East Jerusalem. They applied the same strategy in the occupied West Bank and Golan Heights. But victory and occupation did not bring peace. Israel fought its Arab neighbors again in 1973. They battled Lebanese militias and the Palestine Liberation Army, or PLO, in the north. Although Israel returned the Sinai in 1981, terror campaigns persisted through the '70s and '80s in the West Bank and Gaza. Hoping to eventually trade land for peace, Israel gambled on a 1993 plan negotiated in Oslo. ROSS: The main thing that Oslo produced was mutual recognition between Israel and the PLO. For the PLO, recognition of Israel meant, "All right, we are now accepting a two-state solution." For the Israelis to accept the PLO meant that they were accepting, in effect, the PLO agenda, and they knew the PLO agenda was statehood. KAMAL ABDUL FATTAH: If you accept the idea of having a Palestinian state-- and we insist on having a Palestinian state, you know-- we need a capital. And the only capital that could be from a geographical point of view for what would be a Palestinian state in the West Bank would be Jerusalem. IRA SHARKANSKY: The basis of our claim is that we're here. There's been a Jewish majority of the Jerusalem population since the middle of the 19th century. And now we are 72% of the population. NARRATOR: MAHDI ABDUL HADI: But that population is still heavily concentrated in the west, reinforcing some Arabs' hope for partition and sovereignty. They can share functional arrangement in the city, but they cannot share sovereignty. It has to be split, it has to be divided, between Arab Palestinian sovereignty and Israeli sovereignty. NARRATOR: In 2000, President Clinton and Ambassador Ross helped Israeli and Palestinian negotiators hammer out many details of an agreement. Jerusalem was finally on the table. But like most Israelis, Prime Minister Barak could not imagine a divided city. Ross argued the Palestinian case. ROSS: At one point, I said to him, "Mr. Prime Minister, you are the one "who believes in the concept of separation. "Well... look at East Jerusalem, "where you have Arab neighborhoods "that are exclusively Arab neighborhoods, "where Israelis don't live in them, Israelis don't go to them. "What is the logic of keeping them under your sovereignty if you accept the concept of separation?" And the Israelis found that to be a pretty compelling argument. NARRATOR: So the negotiators drew maps that would split the city along ethnic lines. The bigger problem came with the oldest part of the city, a zone whose importance was all out of proportion to its size. ROSS: The Old City is one square kilometer. Within one square kilometer there are at least 57 holy sites, holy to three separate faiths. The area is so small that if you spring a leak in one quarter, you have to turn off water in the adjacent quarter. So concepts of sovereignty as they apply to the Old City are a little bit more complicated. NARRATOR: At the core are the Haram al-Sharif for the Muslims, or the Temple Mount for the Jews. These Jews are praying in front of their ancient Temple, whose ruins lay buried behind its Western Wall. On top of those ruins are the holy Dome of the Rock and the al-Aqsa Mosque. In traditional real estate terms, both sides claim the same ground. A breakthrough required spatial imagination. ROSS: The Jewish Quarter extends to the wall and the Muslim Quarter envelopes where the Haram is. And you had... the wall is here, the Haram is up here, and the Temple would be behind where the wall was. One Israeli negotiator actually put it quite well-- that for Israel, there was a dead reality that was extremely important for them to be able to protect, which was underground. It's a dead reality in the sense that nobody lives with it every day except emotionally, psychologically, spiritually. The live reality is what people do every day on the surface, where the Haram is. So we were coming up with an approach that was designed to protect the dead reality for Israel, while also governing the live reality for the Palestinians. The Israelis in the end, again, reluctantly accepted, and Yasser Arafat could not accept. NARRATOR: After Arafat's denial, the talks broke down. To Israelis, Barak failed to deliver peace after offering unprecedented concessions. His opponent, Ariel Sharon, unleashed Arab rage when he brought armed guards to tour the Haram al-Sharif. ROSS: It was obviously something that was bound to be seen as provocative. NARRATOR: But Ross does not blame the intifada on Sharon. Rather, it was a failure of Palestinians to curb the violence, and it was the ongoing Israeli occupation. ROSS: I think it was the absence of real change in terms of Palestinian control, at least in Palestinian eyes. The Israelis continued to control too many aspects of day-to-day life for the Palestinians. NARRATOR: So, will there ever be peace? Not soon, according to Ross. But if it comes, it will be based on two states, both with capitals in a divided Jerusalem. ROSS: I do believe that the ideas that President Clinton put on the table will ultimately provide the base for what will emerge as an outcome. NARRATOR: As teachers, you can prepare your students to monitor events as they unfold, comparing the outcome to the plan. GIL LATZ: A ten-minute case study, of course, can't do justice to this difficult human problem, steeped as it is in such extreme cultural, religious and historical complexity. Geography can provide useful tools to help sort out the important factors. Here, at the center of 50 years of modern territorial conflict, are the Palestinians, a stateless people, struggling to establish a sovereign territory of their own, yet seemingly unwilling to unequivocally accept the national and political legitimacy of their Israeli neighbors. A geographer's view of the intersection of politics and culture depends on which scale we adopt for our analysis. At one scale, we can see the way religious values imbue particular places with sacred meaning. For example, Judaism's Western Wall and Islam's Dome of the Rock. Who should exercise sovereignty over sites sanctified as holy? At another scale, we see Israel, primarily Jewish in its religious orientation, but located in the heart of a vast Islamic world. A geographic perspective helps us better understand the complex forces buffeting this region, and better understanding may someday help untangle this profoundly difficult human and territorial conflict. SUSAN HARDWICK: This Jerusalem case study provides an excellent opportunity to talk about the role of religion in shaping some of the world's most distinctive landscapes. Human geographers are fascinated by religious patterns on Earth because religion is one of the earliest and one of the most enduring features of culture. In the northwestern Chinese city of Lanzhou, an overlapping tapestry of religions has shaped the urban landscape. Once populated by a mosaic of religious and ethnic groups from China and Tibet, this ancient rest stop along the Silk Road today is home to two dominant groups, Han Chinese and Muslims. On the other side of the world, in Guatemala, Mayans worship in a Catholic church, practicing a religion forced on their ancestors by Spanish explorers and priests. The cultural landscape here reflects a blend of the transplanted Catholic and native Mayan religions. There can be no question that religion today plays a crucial role in shaping cultural and political landscapes, and will continue to shape our world in the years to come. BINKO: The case study of Jerusalem provides a compelling example of a centuries-long struggle for land within a region, a struggle intensified by deeply rooted cultural and religious differences. In the following lesson, our teacher, Ungennette Brantley Harris, has her ninth-grade students address the issue of what it means to live in the midst of such struggle. Her class has already studied the foundations and beliefs of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. They have also discussed the sources of conflict between the Israeli and Palestinian peoples. Now they continue that discussion and raise the issue of what it means to be a refugee in one's own homeland. As they design refugee camps and propose solutions to this conflict, they are attentive to multiple perspectives and points of view. Here, their objective and ours is one and the same: to evaluate the impact of multiple spatial divisions on peoples’ daily lives. By the end of Ungennette's lesson, I think you will agree with me that her students have a far better and more personal understanding of the consequences of living in contested space. HARRIS: Well, with this Middle East unit, you know, they did do a research on the three major religions, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. So, you know, they had to come up with the symbols and find out what's the differences and what's the similarities. So they really got really involved in that, because a lot of them, you know, go to Sunday school, so they were able to relate back. And they had no idea that the same places that they were studying in the Bible were these places now that we're talking about. We've been talking about the Middle East and we've been looking at the Israeli-Palestinian problem. Okay, why are Palestinians now refugees in their own homeland? Why are they refugees, Sean? SEAN: Because they lost wars. HARRIS: Okay, they lost wars. What wars were those? What wars, Chris? CHRIS: Wars against Jewish people. Okay, against the Jewish people. Why are now Jewish people in what was once called Palestine? Why are they there? Why are they there, Rakisha? HARRIS: Because it was their homeland. It was their original homeland. Why is that? Why do they consider it to be their original homeland? Um... Carolyn, help her. CAROLYN: That was where their religion came from. HARRIS: Okay, they started... Their religion started there, okay, good. Once they fought the war of 1948, then land became occupied by the Jewish people. What are those three major occupied lands in Israel? What are the three... Levaris? LEVARIS: Golan Heights. West Bank. And the Gaza Strip. HARRIS: And the Gaza Strip, okay. What does it mean when you say they are occupied? Chelsea. CHELSEA: The Israeli soldiers guarding it. HARRIS: All right, the Israeli soldiers guard the borders between those places. Now, what other people are being forced into refugee camps? Uh, Anthony. ANTHONY: Afghans. HARRIS: The Afghans, okay. I thought it was important, because after September 11, the kids really did not have a grasp of what was going on in the world, and I figured that they needed to get in touch with what was going on in the Middle East and then we could understand better what had happened on September 11. So the last time that we were in here, we worked on... You were brainstorming some problems in refugee camps. You had some potential problems that might have come up. And then you were going to come up with some solutions to those problems. So what we're going to do today is, we're going to get back into your group. I'm going to give you a chart piece of paper. Once you finish getting down... I want the immediate problem, what would be some potential problems, and how are you going to solve those immediate problems. Then, once you finish that, you're going to put your chart paper up on the board and someone from your group is going to explain what you came up with. What I need you to do now is, get into your groups. Number one, ten people to a room. GIRL: Very overcrowded. Yeah. CAROLYN: The second would be hardly no water. GIRL: The hygiene. CAROLYN: The hygiene is... If I was in a refugee camp, it would be one of my problems. Stinks. HARRIS: Yeah, you guys. Once you say you're going to build, you got to come up with... Where are you going to get the money to build? STUDENT: So we have to write that down under "solution." Yeah, once you decide what it is, you sure do. STUDENT: Think that a fund raiser would come up with all the money to build a building? It should, all the money they get on TV. HARRIS: What if nobody gives to the fund raiser? What if nobody gives any money to the fund raiser? ~(\students talk \over each other\) Okay. HARRIS: It's basically more to make them start thinking. Fill-in-the-blanks or multiple choice, that is short-term, and tomorrow, they will not remember one thing about it. But if you ask them why, and go into more detail-"how did that happen?",…you know-- they will begin to at least start thinking about it. They might not come up with the answer that you want them to come up with, but they will start to think, and then you can probe more into that. And what's the purpose of the water filters? BOTH: Purify the water. HARRIS: Okay, make sure you say all of that, because... Okay, get water filters to purify the water. BOTH: Well, it is on, like... It's in the Gaza Strip. Yeah, and this is the little thing, right here. So they can have a pump reaching out to here, bringing their water close to the filter system. And there you have it. And that's where they get the water. HARRIS: Two minutes, two minutes. Put your final touches. We're going to start over here, with this group here. And they'll explain what they came up with, and then we'll just follow suit all the way around. STUDENTS: Our immediate problems, we only had three that we felt like were a major problem right up front, and that was: no water, overcrowdedness, and no resources. Like, they didn't have any natural resources, because they're in the desert. And then, for potential problems, we had natural disasters, curfew and economy, because they've got jobs and money, but if they, it might, if they get put on curfew, they won't anymore, because they won't be able to leave the camp. And then, for our solutions, we've got: take up donations from other countries to help build wells. For food, we're going to grow crops, and food in the wintertime, we're going to have a storage to put that food in. And, like, to lift up their self-esteem, we're going to give the people jobs. Some of them can be sanitation workers for littering, some of them can be farmers for the food, some of them can clean the houses, and some of them can be teachers, teach the kids. HARRIS: If you lift up their self-esteem-- I like that word-- if you do this, then maybe the people would be willing to give a hand to improve their camp. So that's a good thing in itself. BOTH: Well, for our first problem of no clean water, we decided to, like, put pipelines. See, the women had to walk to the nearby villages to get water. Why don't we just build pipelines so that water could be transported from one village to another? And then we could get them water filters to clean and purify the water. Okay. And then, for medical problems... See, we can't solve all the medical problems that are out there, because we can't even solve our own, so we could get them vaccinations for the medical problems that we do know of, that we can slow down the sickness rate just a little bit, if we could. HARRIS: Okay, uh, you came up with some good problems from reading those articles, the problems that were there. And coming up with some solutions. And I think it goes back to, one of the groups had said, if selfesteem... If you don't have any place to go and to build up your selfesteem, then I think maybe some of the other little things could fall into place. That's good, that's real good. Now, what I want you to do now is to get back with your groups. Then I'm going to give you a sheet of paper, and you're going to create a better refugee camp. And you have a requirement sheet that will go along with that map, okay? Every refugee camp on your site map will have a small body of water near you. But there's a lot of people in this little space. You got to think about how many people... GIRLS: 16 people per house. Shoot, that's a lot of people. How many refugees do we have? 150, at present... 120, at present. And you're going to be... Your camp will hold 250. STUDENT: It will hold 250, but we only have 120. HARRIS: You only have 120 at present, right. HARRIS: Now, you're going to have to cut these out. These are the things that you will have to put in your refugee camp. STUDENT: Yeah, we got to have enough room to get the landfill five inches away from them. HARRIS: You have enough space, I believe. STUDENTS: You said, "Put 15 houses on the map," right? All right, we have three corners. I was saying, why don't you put five houses in each corner. That's your choice. I'm saying, you have five houses in each corner, and then, right around in the middle, in the center of the corner... Just like a little town, you have your medical places and the bathrooms. But the bathrooms can be a little bit farther out from the center. Well, where are you going to put your trash? STUDENT: See, you got to put the trash down near the... HARRIS: Where are you going to put your trash? You got trash to put somewhere. Put your bathroom closer to the landfills. Where are you going to put your wells? The most important thing that every one of you said, water was a problem. Where are you going to put your wells? STUDENTS: And the main road coming from, like, out here up through here. And, like, off the main road, have tributaries. Okay. That's still, like, half an inch, all right. Yeah, that's more than enough. How far does... It doesn't say how far this has to be from the... STUDENT: This house is just... HARRIS: Okay. The bell is getting ready to ring. When we come back on Tuesday, we'll finish up these and let us look at... See who used their space the wisest. HARRIS: Geography, as most people will acknowledge, you know, is memorizing places. That's not important, to memorize. You know, to know the country and the capital. That's good, I guess, if you wanted to know trivial stuff. But, you know, they need to understand place, and why is the Middle East a volatile region right now. Why is it so conflicting right now? And what does culture and religion have to do in an area? So if they understand location, place, movement, human-environmental interaction, then they can understand what geography is all about. This lesson presents some very important geographic concepts. JIM BNKO: As Ungennette's students grapple with the problems posed by refugee camps, they see in concrete and specific terms how the forces of cooperation and conflict among people influence control of a region. These students also explore how deeply felt cultural and religious beliefs can affect people's perceptions of place. Ungennette's students have gained an appreciation for the complexity of the causes and the effects of human conflict.