Chapter 12: Fundamentals of Thermal Radiation Yoav Peles

advertisement

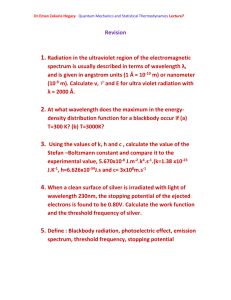

Chapter 12: Fundamentals of Thermal Radiation Yoav Peles Department of Mechanical, Aerospace and Nuclear Engineering Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute Objectives When you finish studying this chapter, you should be able to: • Classify electromagnetic radiation, and identify thermal radiation, • Understand the idealized blackbody, and calculate the total and spectral blackbody emissive power, • Calculate the fraction of radiation emitted in a specified wavelength band using the blackbody radiation functions, • Understand the concept of radiation intensity, and define spectral directional quantities using intensity, • Develop a clear understanding of the properties emissivity, absorptivity, relflectivity, and transmissivity on spectral, directional, and total basis, • Apply Kirchhoff law’s law to determine the absorptivity of a surface when its emissivity is known, • Model the atmospheric radiation by the use of an effective sky temperature, and appreciate the importance of greenhouse effect. Introduction • Unlike conduction and convection, radiation does not require the presence of a material medium to take place. • Electromagnetic waves or electromagnetic radiation ─ represent the energy emitted by matter as a result of the changes in the electronic configurations of the atoms or molecules. • Electromagnetic waves are characterized by their frequency n or wavelength l l c n (12-1) • c ─ the speed of propagation of a wave in that medium. Thermal Radiation • Engineering application concerning electromagnetic radiation covers a wide range of wavelengths. • Of particular interest in the study of heat transfer is the thermal radiation emitted as a result of energy transitions of molecules, atoms, and electrons of a substance. • Temperature is a measure of the strength of these activities at the microscopic level. • Thermal radiation is defined as the spectrum that extends from about 0.1 to 100 mm. • Radiation is a volumetric phenomenon. However, frequently it is more convenient to treat it as a surface phenomenon. Blackbody Radiation • A body at a thermodynamic (or absolute) temperature above zero emits radiation in all directions over a wide range of wavelengths. • The amount of radiation energy emitted from a surface at a given wavelength depends on: – the material of the body and the condition of its surface, – the surface temperature. • A blackbody ─ the maximum amount of radiation that can be emitted by a surface at a given temperature. • At a specified temperature and wavelength, no surface can emit more energy than a blackbody. • A blackbody absorbs all incident radiation, regardless of wavelength and direction. • A blackbody emits radiation energy uniformly in all directions per unit area normal to direction of emission. • The radiation energy emitted by a blackbody per unit time and per unit surface area (Stefan–Boltzmann law) Eb T s T 4 s=5.67 X 10-8 W/m2·K4. W/m 2 (12-3) • Examples of approximate blackbody: – snow, – white paint, – a large cavity with a small opening. • The spectral blackbody emissive power C1 Ebl l , T 5 l exp C2 lT 1 W/m 2 μm C1 2 hc02 3.74177 108 C2 hc0 / k 1.43878 104 μm K W μm 4 m 2 (12-4) • The variation of the spectral blackbody emissive power with wavelength is plotted in Fig. 12–9. • Several observations can be made from this figure: – at any specified temperature a maximum exists, – at any wavelength, the amount of emitted radiation increases with increasing temperature, – as temperature increases, the curves shift to the shorter wavelength, – the radiation emitted by the sun (5780 K) is in the visible spectrum. • The wavelength at which the peak occurs is given by Wien’s displacement law as lT max power 2897.8 m m K (12-5) • We are often interested in the amount of radiation emitted over some wavelength band. • The radiation energy emitted by a blackbody per unit area over a wavelength band from l=0 to l l1 is determined from l1 Eb,0l1 T Ebl l , T d l 0 W/m2 (12-7) • This integration does not have a simple closed-form solution. Therefore a dimensionless quantity fl called the blackbody radiation function is defined: f ln T ln 0 Ebl l , T d l sT 4 ; n 1 or 2 • The values of fl are listed in Table 12–2. (12-8) Table 12-2 ─ Blackbody Radiation Functions fl f l1 T l1 0 Ebl l , T d l sT 4 (12-8) f l1 l2 T f l2 T f l1 T (12-9) Radiation Intensity • The direction of radiation passing dA through a point is best described in spherical coordinates in terms of the zenith angle q and the azimuth angle f. • Radiation intensity is used to describe how the emitted radiation varies with the zenith and azimuth angles. • A differentially small surface in space dAn, through which this radiation passes, subtends a solid angle dw when viewed from a point on dA. n • The differential solid angle dw subtended by a differential area dS on a sphere of radius r can be expressed as dS d w 2 sin q dq df r (12-11) • Radiation intensity ─ the rate at which radiation energy is emitted in the (q,f) direction per unit area normal to this direction and per unit solid angle about this direction. dQe dQe W (12-13) I e q , f dA cos q dw dA cos q sin q dq df m2 sr • The radiation flux for emitted radiation is the emissive power E dQe dE I e q , f cos q sin q dq df dA (12-14) • The emissive power from the surface into the hemisphere surrounding it can be determined by E dE 2 /2 f 0 q 0 I e q , f cos q sin q dq df 2 W m (12-15) hemisphere • For a diffusely emitting surface, the intensity of the emitted radiation is independent of direction and thus Ie=constant: E hemisphere dE I e 2 /2 f 0 q 0 cos q sin q dq df I e (12-16) • For a blackbody, which is a diffuse emitter, Eq. 12–16 can be expressed as Eb I b (12-17) • where Eb=sT4 is the blackbody emissive power. Therefore, the intensity of the radiation emitted by a blackbody at absolute temperature T is sT 4 I b T Eb W m2 ×sr (12-18) • Intensity of incident radiation Ii(q,f) ─ the rate at which radiation energy dG is incident from the (q,f) direction per unit area of the receiving surface normal to this direction and per unit solid angle about this direction. • The radiation flux incident on a surface from all directions is called irradiation G G dG 2 /2 f 0 q 0 I i q , f cos q sin q dq df (12-19) W m 2 hemisphere • When the incident radiation is diffuse: G Ii (12-20) • Radiosity (J )─ the rate at which radiation energy leaves a unit area of a surface in all directions: J 2 /2 f 0 q 0 I e r q , f cos q sin q dq df W m 2 (12-21) • For a surface that is both a diffuse emitter and a diffuse reflector, Ie+r≠f(q,f): J I e r ( W m2 ) (12-22) • Spectral Quantities ─ the variation of radiation with wavelength. • The spectral radiation intensity Il(l,q,f), for example, is simply the total radiation intensity I(q,f) per unit wavelength interval about l. • The spectral intensity for emitted radiation Il,e(l,q,f) dQe W I l ,e l , q , f 2 dA cos q dw d l m sr μm (12-23) • Then the spectral emissive power becomes El 2 f 0 /2 q 0 I l ,e l ,q , f cos q sin q dq df (12-24) • The spectral intensity of radiation emitted by a blackbody at a thermodynamic temperature T at a wavelength l has been determined by Max Planck, and is expressed as 2hc02 Ibl l , T 5 l exp hc0 l kT 1 W/m2 sr μm (12-28) • Then the spectral blackbody emissive power is Ebl l , T Ibl l , T (12-29) Radiative Properties • Many materials encountered in practice, such as metals, wood, and bricks, are opaque to thermal radiation, and radiation is considered to be a surface phenomenon for such materials. • In these materials thermal radiation is emitted or absorbed within the first few microns of the surface. • Some materials like glass and water exhibit different behavior at different wavelengths: – Visible spectrum ─ semitransparent, – Infrared spectrum ─ opaque. Emissivity • Emissivity of a surface ─ the ratio of the radiation emitted by the surface at a given temperature to the radiation emitted by a blackbody at the same temperature. • The emissivity of a surface is denoted by e, and it varies between zero and one, 0≤e ≤1. • The emissivity of real surfaces varies with: – the temperature of the surface, – the wavelength, and – the direction of the emitted radiation. • Spectral directional emissivity ─ the most elemental emissivity of a surface at a given temperature. • Spectral directional emissivity e l ,q l ,q , f , T I l ,e l , q , f , T Ibl l , T (12-30) • The subscripts l and q are used to designate spectral and directional quantities, respectively. • The total directional emissivity (intensities integrated over all wavelengths) eq q , f , T I e q , f , T I b T • The spectral hemispherical emissivity El l , T el l,T Ebl l , T (12-31) (12-32) • The total hemispherical emissivity e T E T (12-33) Eb T • Since Eb(T)=sT4 the total hemispherical emissivity can also be expressed as e T E T Eb T 0 e l l , T Ebl l , T d l sT 4 (12-34) • To perform this integration, we need to know the variation of spectral emissivity with wavelength at the specified temperature. Gray and Diffuse Surfaces • Diffuse surface ─ a surface which properties are independent of direction. • Gray surface ─ surface properties are independent of wavelength. Absorptivity, Reflectivity, and Transmissivity • When radiation strikes a surface, part of it: – is absorbed (absorptivity, a), – is reflected (reflectivity, r), – and the remaining part, if any, is transmitted (transmissivity, t). Absorbed radiation Gabs (12-37) a Incident radiation G Gref Reflected radiation • Reflectivity: (12-38) r Incident radiation G Transmitted radiation Gtr (12-39) • Transmissivity: t Incident radiation G • Absorptivity: • The first law of thermodynamics requires that the sum of the absorbed, reflected, and transmitted radiation be equal to the incident radiation. Gabs Gref Gtr G (12-40) • Dividing each term of this relation by G yields a r t 1 (12-41) • For opaque surfaces, t=0, and thus a r 1 (12-42) • These definitions are for total hemispherical properties. • Like emissivity, these properties can also be defined for a specific wavelength and/or direction. • Spectral directional absorptivity a l ,q l ,q , f I l ,abs l ,q , f I l ,i l , q , f (12-43) • Spectral directional reflectivity rl ,q l ,q , f I l ,ref l ,q , f I l ,i l , q , f (12-43) • Spectral hemispherical absorptivity al l Gl ,abs l Gl l (12-44) • Spectral hemispherical reflectivity rl l Gl ,ref l Gl l (12-44) • Spectral hemispherical transmissivity t l l Gl ,tr l Gl l (12-44) • The average absorptivity, reflectivity, and transmissivity of a surface can also be defined in terms of their spectral counterparts as a 0 a l Gl d l 0 Gl d l , r 0 rl Gl d l 0 Gl d l , t l Gl d l t Gl d l 0 (12-46) 0 • The reflectivity differs somewhat from the other properties in that it is bidirectional in nature. • For simplicity, surfaces are assumed to reflect in a perfectly specular or diffuse manner. Kirchhoff’s Law • Consider a small body of surface area As, emissivity e, and absorptivity a at temperature T contained in a large isothermal enclosure at the same temperature. • Recall that a large isothermal enclosure forms a blackbody cavity regardless of the radiative properties of the enclosure surface. • The body in the enclosure is too small to interfere with the blackbody nature of the cavity. • Therefore, the radiation incident on any part of the surface of the small body is equal to the radiation emitted by a blackbody at temperature T. G=Eb(T)=sT4. • The radiation absorbed by the small body per unit of its surface area is Gabs a G as T 4 • The radiation emitted by the small body is Eemit es T 4 • Considering that the small body is in thermal equilibrium with the enclosure, the net rate of heat transfer to the body must be zero. Ases T 4 Asas T 4 • Thus, we conclude that e T a T (12-47) • The restrictive conditions inherent in the derivation of Eq. 12-47 should be remembered: – the surface irradiation correspond to emission from a blackbody, – Surface temperature is equal to the temperature of the source of irradiation, – Steady state. • The derivation above can also be repeated for radiation at a specified wavelength to obtain the spectral form of Kirchhoff’s law: • This relation is valid when the irradiation or the emitted radiation is independent of direction. e l T a l T (12-48) • The form of Kirchhoff’s law that involves no restrictions is the spectral directional form e l ,q T al ,q T Atmospheric and Solar Radiation • The energy coming off the sun, called solar energy, reaches us in the form of electromagnetic waves after experiencing considerable interactions with the atmosphere. • The sun: – – – – – is a nearly spherical body. diameter of D≈1.39X109 m, mass of m≈2X1030 kg, mean distance of L=1.5X1011 m from the earth, emits radiation energy continuously at a rate of Esun≈3.8X1026W, – about 1.7X1017 W of this energy strikes the earth, – the temperature of the outer region of the sun is about 5800 K. • The solar energy reaching the earth’s atmosphere is called the total solar irradiance Gs, whose value is Gs 1373 W/m 2 (12-49) • The total solar irradiance (the solar constant) represents the rate at which solar energy is incident on a surface normal to the sun’s rays at the outer edge of the atmosphere when the earth is at its mean distance from the sun. • The value of the total solar irradiance can be used to estimate the effective surface temperature of the sun from the requirement that 4 L G 4 r s T 2 2 s 4 sun (12-50) • The solar radiation undergoes considerable attenuation as it passes through the atmosphere as a result of absorption and scattering. • The several dips on the spectral distribution of radiation on the earth’s surface are due to absorption by various gases: – oxygen (O2) at about l=0.76 mm, – ozone (O3) • below 0.3 mm almost completely, • in the range 0.3–0.4 mm considerably, • some in the visible range, – water vapor (H2O) and carbon dioxide (CO2) in the infrared region, – dust particles and other pollutants in the atmosphere at various wavelengths. • The solar energy reaching the earth’s surface is weakened considerably by the atmosphere and to about 950 W/m2 on a clear day and much less on cloudy or smoggy days. • Practically all of the solar radiation reaching the earth’s surface falls in the wavelength band from 0.3 to 2.5 mm. • Another mechanism that attenuates solar radiation as it passes through the atmosphere is scattering or reflection by air molecules and other particles such as dust, smog, and water droplets suspended in the atmosphere. • The solar energy incident on a surface on earth is considered to consist of direct and diffuse parts. • Direct solar radiation GD: the part of solar radiation that reaches the earth’s surface without being scattered or absorbed by the atmosphere. • Diffuse solar radiation Gd: the scattered radiation is assumed to reach the earth’s surface uniformly from all directions. • Then the total solar energy incident on the unit area of a horizontal surface on the ground is: Gsolar GD cos q Gd W/m 2 (12-49)