Document 17878503

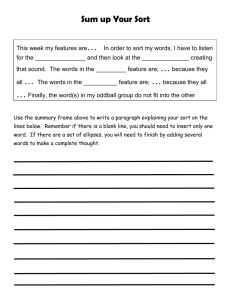

advertisement