17911 >> Kirsten Wiley: What if you never had to... sensing and computing will bring about an e-memory revolution in...

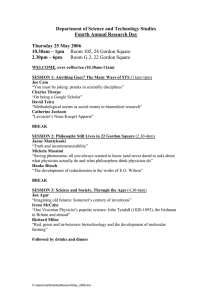

advertisement

17911 >> Kirsten Wiley: What if you never had to forget anything? Trends in storage, sensing and computing will bring about an e-memory revolution in the next 100 years that will enable you to record as much of your life as you want, in previously unimaginable detail. Everything you see here, every step you take, every heartbeat, all of it can be captured digitally. You can have total recall. Total recall will revolutionize our health, our learning, our productivity. It will change the story we pass on to prosperity, taking us to a level of digital immortality. The consequences to society will be profound. Some good and some bad. But good or bad, our experiences with the MyLifeBits project and the CARPE research community has convinced us that the e-memory revolution is inevitable. Jim Gemmell is a senior researcher at Microsoft Research. He's currently working on the next generation of search. Previously, Jim's research focused on MyLifeBits, part of the CARPE research community, whose first and second workshops he was proud to chair. Jim has also done research on the topics of personal media management, enhancement, telepresence and reliable multi-cast. His research has led to features in Windows XP, Windows Server 2008, Windows 7 and bing.com. He lives in the Bay Area. And Gordon Bell has been a principal researcher at Microsoft Research since 1995. He's a former vice president of R&D at Digital Equipment Corporation, professor at Carnegie Mellon University, founding assistant director of the National Science Foundation's [indiscernible] directorate, advisor, investor to 100 plus high tech start-up companies and founding trustee of the Computer History Museum in Mountain View. He's written several books about computer architecture and high tech ventures. Gordon created ACM's Gordon Bell Prize in 1987 to acknowledge and reward progress in parallel progressing. He's a fellow of the ACM, American Academy of Arts and Sciences, IEEE, NAE, NAS and the 1991 National Medal of Technology Medallist. Please welcome me -- join me in welcoming Jim Gemmell and Gordon Bell. [applause] >> Jim Gemmell: Here we go. Hello. We're here to talk to you about our book "Total Recall" and there's so much to talk about and so little time we have here. Of course, it takes a whole book to go in depth. What I'm going to try to do is get through the material quickly and have plenty of time to have a discussion with the points that are of particular interest to you. So I'm qualified to speak on the subject because I'm losing my mind, which is not to say that I need -- hello. >>: Hello. >> Jim Gemmell: Is that better? Did anything just happen? Okay. Not that I'm going crazy, but that I need things like this. And hopefully Gordon and I find the car where we parked in the parking lot afterwards. That's the way it goes with me these days. But what if you could remember absolutely everything? What if you could remember everything you've ever read, everything you've ever seen, everything you've ever heard and much more beyond what you think of as human memory typically? What's the temperature in the room right now? What's the humidity? Sensors all over the place. The premise of the book is that soon, if you want, you can have total recall, as much or as little as you like, but certainly way more than ever before. Even the people who we think are recoiling at the notion of this will still have a record of their life that would have blown away previous generations. There's three streams of technology that are going to take us for sure down the road to total recall. The first is recording devices. They're already all over the place, digital cameras are going crazy out there. We carry around cell phones, think of what you can do with a cell phone, audio recording and video recording, we can take pictures. Some of them have your location. They're amazing devices for recording. As we go forward, pretty much everything that can be instrumented will be instrumented, in a world just full of sensors. The second stream is storage. We all know it's so incredibly cheap and abundant and just getting more so all the time. We can store all this stuff. And the third stream is software. The software to find the stuff, to recall it, to search for things, to do analysis, to do data mining, to visualize to us and help us make sense of it and manage it. Based on those three streams of technology, and what we've learned from our own experience, we believe the next 10 years is going to see a revolution in the world. It's going to change society for sure and that total recall is inevitable. To clarify, what we're not talking about is life blogging. If you are one of those people who like to post, if you're like Jenny with the Jenny Cam or someone on Justin TV and you like to publish your life, go ahead, fine. I'm not going to tell you not to, but I think you're crazy. We would never do anything like that. For us, we think of it more like this: It's my diary with a lock on it. It's personal. It's intimate. It's for my benefit, nobody else's. And if I share, I'm going share a little bit very carefully. Now, it's my personal preference, but that's what this is all about. If you want to take that and share it, that's a different topic. So before we get into it we're going to talk a lot about -- can you just hold for a second? Again, I want to get through the material and we'll field a lot of questions at the end, because I promise you, we don't have time to even cover a bit of the book here. We'll leave a lot untouched. I want to make sure we get through things. What I want to do is tell you a little bit about our background, how we got into this. Gordon will describe that, actually. And we'll talk about some of the advantages of total recall that we've learned and societal implications. Gordon, why don't you take it away now. We've got the arrows on there. >> Gordon Bell: Okay. Let's see. It all kind of started back in October '98 when Raj Reddy sent me an e-mail and said: Can I take some of your books and scan them, because we're starting the Million Book Project and we want to see about formatting and how you do it and what the quality, just generally do some experiments with those books. So I said, sure, don't worry about copyrights, because Microsoft has a lot of lawyers. Now, it turns out at that particular point in time those lawyers were pretty busy. [laughter]. And so fortunately -- I don't think they would have been very happy if I had come to them with one more problem. So anyway but that was the beginning. Actually stimulated me thinking, because I'd been carrying boxes of papers around for a long time, and I started doing some scanning experiments. And just to see what formats you use and how good the recognizers were in terms of OCRs, because in fact scanning per se is no good unless the computer knows what their scanning. So basically the whole thesis of MyLifeBits is the computer's gotta know everything it's got in there. And that's a challenge for you guys, which is to make it that way. So whether it's a picture or whatever, or voice or whatever, the computer's got to understand that stuff. And that's all of the work for you to do, whether it's face recognition or voice recognition or what. But those are the limits right now. And what we said was we did that, did a lot of scanning. In about 2000, we had gotten kind of production going, and I said well why is it paper? I've got, I don't know, people -- you'd give a talk and you'd walk away with a videotape or you go to someplace, you get a coffee mug or something like that. And I said, "Why just can paper? We want to scan everything." Basically anything that can be digitized must be digitized. And we want to get rid of clutter. So it was at that point we decided it was going to be everything. And those things were all the goal was to encode everything into the hard drive. And also along about that time it was, well, we said, gee, we'll be at a terabyte in maybe six or seven years. And with the terabyte you should be able to put your whole life, at least at some resolution, or at least given you have a terabyte, what would you do with it? I think that's the way we kind of went, and started allocating space to that in terms of e-mail. And at that point in time, you'll note these are very low resolutions, who would ever think of just having a 400 kilobyte JPEG image. But at that point in time 400 kilobytes looked like a lot. I remember looking at the first 100 kilobyte things, looks pretty good. That's when you had the first quarter mega pixel cameras. So anyway this was what a terabyte would look like. Now I'd say the reasonable number would be 10 terabytes at low resolution if you want to record video and audio. Now, if you want to have high fidelity, well, then, you're talking tens of terabytes and petabytes depending on the resolution, because video is whatever you want from that. It turns out, with that, with those budgets, why, then a terabyte would give you 65 years, which I thought was about enough. Since then I've gone past that. And it turns out that it's right now I'm at about a gigabyte a month. And on that list I didn't have -- I guess I did have every Web page that I looked at. So a lot of that are really the Web pages that are looked at and then e-mail now has lots of attachments. And then the photos are bigger and so on. But at least the number is about a -that I'm of the stuff I'm recording, a terabyte will hold at that resolution, but I don't think that that's realistic for the life that we'd like to have there. So basically it is that in these kinds of things that we are our own data. So if you look in my collection, there's all kinds of artifacts, whether it's paintings or postcard or a card from my granddaughter or pins or medals or whatever, a pennant, or just photographs and family kind of -- that was the goal to show you at the very beginning the kinds of stuff, the range of things that in fact virtually nothing is off limits kind of. So what you saw was pretty much the guts of what's in there. And then you certainly have all of these things of various medals, awards, stuff like that. But some of the harder things are notebooks. The nice thing is or the good news or the bad news is people don't really have the -- don't tend to use the engineering, handwritten engineering notes that at least I use. So I had a large number of engineering notebooks that we all scan, and of course those are totally unreadable by -- the computer has no idea what those mean. So books and other artifacts. Here's the document that created some controversy within Microsoft a few years ago. On my website I put the digital equipment VAC strategy note from 1979. And somebody said, "You realize what he's put out there? He's put this --" you'll note it was company confidential -"confidential memo." Come on, folks, the company has been dead or has been integrated into Compaq and then integrated into HP since 19 -- I guess 1992. So it's totally irrelevant. And I put it there for the idea to show people, hey, here's a strategy when people are always talking strategy. Well, I have a strategy, and it worked for about 10 years. People forgot to change it when I left. [laughter]. But basically it got decked to be number two in the computer industry at that time. So you've got it now. So now what do you do with it? And I think Jim's going to take over and I've got it all in there, and now the question is, now what? >> Jim Gemmell: Now what, indeed. So Gordon was off scanning everything. And he was building up this collection, and, yeah, what do you do with it? Can you make any use of it? And eventually he came grumbling into the office saying, "It's all just a bunch of bits." He was really irate. "I can't do anything with this." I thought that's a real problem. We were working for Jim Gray. And Jim, in the height of encouragement, offers to us that we've created the write once read never memory. [laughter] Thanks, Jim, that was really great. But he had a good point. I mean, it was just a bunch of bits. Can we do anything with it? So we said, hey, this is a research project. Gordon's our guinea pig. We're going to run an experiment. He's going to do everything we can think up and we'll start building software. What should software look like if you wanted to digitize your whole life? We started out saying we're going to use a database, use SQL Server, because we did our list of requirements and said if we don't use it, we'll have to build it and that doesn't sound like fun. We started building a suite of software around it. So sucking all our files into that database, writing a shell that lets you browse and search and look at things, letting you make comments in text or with audio, a tool for our browser where we record every Web page that we visit. So that's not just the URL, but an actual copy of the page so that if it disappears off the Web we've still got it. Capturing our chat sessions. Sucking in our e-mail. We set up a rig in Gordon's office. You would phone his office you'd hear a recording, because California law says you need to be notified so you can opt out, hang up. We played for a while with TV and radio recording. That was fun. We created several terabytes of TV recordings and said what would it be like to have tons and tons of TV recorded. The answer was overwhelming. I think there's still a UI challenge there for how to deal with really massive collections of video. But in the end we decided that actually having the radio and television content recorded was not that interesting because we believe it will be all available on demand eventually. What's interesting is the log of what did I watch, when did I watch it? What bored me and I shut it down in the middle? It was very interesting that we were recording the radio, and I started -- I used to always listen to the particular NPR news show. And then I had it on my pocket PC to listen to kind of Tivoed, and I could fast forward. And I discovered I actually only consumed 15 minutes of the typical news hour. Ever since then I've never been able to listen to the NPR news again because I felt like I was wasting 45 minutes, what am I doing here. The screen saver which may be the killer app here because there's so much stuff, you don't remember it's all there; you won't even look for it. The screen severe brings it up to you. And we found also if we want people to interact with the media, they have to be able to do it whenever they feel like it, however they feel like it. Whenever the material appears, you've got to be able to rate it, comment on it, or you might want to follow up or make a note or something like that. So we built a screen saver that did that. We got GPSs and started recording our location and building map displays to render that. I'll tell you about the SenseCam a little bit later. And finally we got software from Mary Truwinsky's team that helped us log everything we're doing with our PC. So what window's in the foreground, how long, how much mouse keyboard activity, what am I doing with my PC. Eventually, here's Gordon's collection in 2008. So by the number of items, lots of Web pages, lots of e-mails, lots of pictures. Not so much of everything else. By space, video dominates and then pictures and audio. And through Gordon's lifetime there's not a lot of video. He didn't have a lot of film. He said, gee, I really wish I had more film, once we got to the stage of this, I realized how little there was from his lifetime. So I think a lot of modern people with their little video recorders and so on will generate far more. The take-away from this slide for all of us in the future will there be video and audio and pictures and anything else will be a drop in the bucket, you will not care. In fact, like Web pages, we realize with Web pages we had this toggle to turn on and off the Web page recording and eventually I'd leave it on, even when I'm debugging my own website because I can't click fast enough to care about how much storage is represented there. It just doesn't matter compared to this other kind of media. And, by the way, it turned out to save my butt a couple times when I hadn't backed up a certain version of code but MyLifeBits had a version of it from the website I was debugging. So then around 2003, would it be, Gordon? Lindsay Williams from the Cambridge Lab came up with a SenseCam. So I would have mine today except for journalists borrowed it from me. It's a camera where you wear around your neck and it has sensors built into it. The idea is it takes pictures automatically at a, quote/unquote, good time. So it has sensors on it. For instance, if the light level changes, say I walk outdoors in the sunshine, it says scene change and take a picture, let's grab where we are now. It has passive infrared detectors, the gray bubble on the front there, like from a burglar alarm, warm body detector. There's a person in front of me, take the picture. It has accelerometers on it. If it's jiggling, it says I'll take a blurry picture right now. I'll wait until it settles and I'll take a nice picture. So trying to get shots automatically. Here's Gordon with the standard issue SenseCam plus digital/audio recorder ready to go and capture. And here's an example of if you take a bunch of SenseCam pictures and put them together in time lapse fashion, you get something like this. This is from a colleague in Cambridge riding the bike down to the train station and purchasing lunch, too. One of the things you enjoy collecting out of the SenseCam are all these sequences of a heap of food on your plate, dissolving down into nothing. You can see it. See the food going on there. And really what we started to get out of this, the point of having automatic capture in our Web browser, having automatic capture with the SenseCam is that you get things you would never get otherwise. It's really interesting. Like in the browser, it's too much work to even click one button that says save. It has to be on. The same with the SenseCam. We all know families where child number one is born and, oh, we take pictures of that cute kid and shoot videos and all this stuff. And eventually you go, I'm tired of being the photographer at the birthday party; I want to be part of the birthday party. And the media drops way off. And child number two says why are there no pictures of me? Don't they love me? And the therapist ensues and all that stuff. But you get these pictures you wouldn't otherwise get when it's automatic with the SenseCam. This is a collection of some of my pictures that are special to me that I got with the SenseCam. Here's a sequence of Peter Hart, head of RICO labs having lunch with me. I never would have got out a camera and snapped all these. But he's very animated while he has lunch with you and you catch the mood of him here. I have Ben Schneiderman, the famous UI researcher when I went to visit him at the University of Maryland. He's on the far right in the middle. Walking up, about to stick his hand out to shake my hand. I caught the moment I met him. In fact, there's a post-doctoral researcher at Dublin City University who wore the SenseCam for an entire year as an experiment. He said, I'm going to wear it every waking moment for a year. At the end I presume I'm going to throw it as far as I can get away from the thing, but we'll do the experiment see how it goes. Actually, when the year ended he refused to give it back, worn it for over three years now. As far as I know he still has it on. He took 800,000 pictures the first year. I think he's well up over three million now. He claims it makes his memory better. He loves it for a number of reasons. But I wanted to point out this idea again of capturing moments you wouldn't otherwise. He said I caught the moment I first ever met my girlfriend before I knew she would become my girlfriend. So that's a pretty neat moment. Capturing your location. Recording meetings. Here's what you get when you're tracking what's going on on your desktop. So Gordon's usage hour by hour. George Robertson did this visualization from in this building. So hour by hour, how much time you're using it. What windows are in the foreground, so what apps are going on, what documents. You get a sort of time study of how you're spending your time with your PC. So in the end, what do we have? MyLifeBits, not a product. I mean a suite of random applications, if you will. But a sort of proof of concept. And we started a workshop at ACM Multimedia looking into life logging issues, the CARPE workshop. We also funded 14 universities and gave them SenseCams and gave them the MyLifeBit software. And they went off and did all kinds of interesting things. We interacted with a lot of people throughout MSR. Between what we played with, what things we developed and what we saw our colleagues develop, we got enough of a taste of it, a little foretaste to say, wow, I think we really see where we're headed. And we liked it. This is a bit of a surprise, because remember we started out, it was just an experiment. People would say why are you doing this? Well, because we can. Because Gordon had this idea of digitizing everything. And then we said, well, if we're going to have a terabyte hard drive, you could really go for it. Let's try it. We didn't know we'd like it or it would be useful. At this point we go, wow, it's actually good. So the heart of our book is five chapters that talk about advantages that we found to total recall, digitizing your life. In memory, health, work, learning and what we leave to posterity, how we enjoy things and tell stories. I'll only have time to touch on a few of them today, even briefly in that, but hopefully I'll give you a flavor of some of this. So, first of all, memory. Human memory is pretty interesting. Very different, our bio memories are very different from electronic memory. Human memory is transient. So we lose things over time. We often assign memory to the wrong source, which, by the way, is deadly with our e-memories because we're sure we're looking for something that someone from a certain source and it's not actually from that source, you can waste a lot of time with that. Bias, this is why they don't like eyewitnesses in a legal case to read the newspapers, because sometimes they have all kinds of interesting occasions where they end up claiming for sure they witnessed something that never happened because they read an account otherwise. Absent-mindedness. So here it's not that you forget it. You don't lose the retention of the memory, but it just won't come to you when you need it. Likewise, that tip-of-the-tongue experience. It's there you about it's just blocked. You just can't bring it up. And of course memory is a strange in many number of ways, we're constantly rebuilding memories and changing them. In contrast, electronic memory is cold calculating, doesn't get bored, keeps all the trivia. Just a few samples here to give you a flavor of it. Greg Smith here at MSR did this visualization, sort of saying here's kind of a breakdown of the ways we can look at some of Gordon's life bits. Let's say we want to look at what do we have from Florida from last year. So once we pick last year it refactors to show you here's what's available from last year. Go into location, and it will show you what we have by location. We can drill down into what's from Florida. And then you might say, well, that's Florida of last year, what do I have from Florida in general, never mind just last year so you can get rid of the restriction of last year and it will refactor to show you that. I did a little screen so I can do that screen capture. Here it is on an 18-panel LCD display. In this high resolution seeing your life laid out, visualization is just fascinating to make sense of things. You think of the scientists with the big datasets. They always want to visualize, right? We're all going to be like scientists with big datasets. We all need to make sense of it, need to visualize things. This is part of Gordon's life. We showed this at Tech Fest a few years ago. When it came up, Gordon just stood in front of it for a long time because it's fascinating that so much of this one is your life and you see your stuff and you start seeing those insights, it's really striking. Electronic memory, simple things in here. Just how you sort things can make things easier to find. I'd been having an e-mail discussion about storage with some people. And I wanted to get back to an e-mail because I remembered that guy said that really cool thing. That's my memory. So how do I find it? Well, I did a search for storage and I found storage in e-mail. I had over 5,000 items. But if I just look at who they're from, and I sort them by frequency, most of them are just from Gordon myself and Jim Gray and it drops off rather quickly and I'm able to scan down a list spot his name and get to it. Even though I don't have a precise starting point I can probably get to some good things. Another example is let's say Gordon has a phone call with his real estate agent, he wants to sell his house. He was selling his house in Los Gatos and she says, yeah, let's look at this, I have a comp for you. Bring up your browser, I'll tell you how to look at the comparable property and we'll talk about it. They talk about it in their phone conversation. They hang up. Time goes on. A week passes. Gordon says I want to look at that comparable property again, what's he going to search for? House? Real estate? Won't get him anywhere with all the stuff he's been looking at. He goes, I know I had this conversation with my real estate agent. If I go in and say let's look at the call and what happened at the same time as that call, then not that much really did happen at the same time. You can scroll down. You can find the page with the house on it, even though it's not on the Web anymore. The point is you start with little memory hook, what do you remember and you kind of browse your way around to it. We found this is the nature of a lot of our searches, you start with something you do remember. Maybe you remember it vaguely, maybe a little bit. You're not sure. You want to hunt and browse and go on correlations and things that are linked in our system and help you get to what you want. Another area of advantage, and the one that excites me the most about total recall, is health. Gordon was in for a bypass surgery at Stanford Hospital. And I went in to visit him. And the doctor came in in the middle and checked him out and looked at his chest. He peeled back and he looks at it, goes, yeah, looks like it's getting better. Gordon everything's excellent, way to go. See you later, walks out of the room. I said what was that all about? Gordon said, I've got this blotch on my chest here. They're worried it might indicate an infection. If I'm infected, I have to stay in the hospital. If not, I can leave and it's my birthday this weekend and I really want to be home and have a birthday party. Great you're getting better and get to go home. He said, yeah, it's great I'm going home but I'm not getting any better. I said, what do you mean you're not getting any better. The doctor just said you're getting better. He said I'm getting better but I know I'm not getting better. How do you know you're not getting better? I know because I've been taking pictures of it every day with my digital camera. And it's actually exactly the same. [laughter]. Our present medical system needs to change. Already the paper system is letting us down. Even though virtually always people have the chart available, also virtually always there's problems with missing information. RAND says we can save $77 billion a year if we had electronic systems and we'd save, we could save maybe 100,000 lives because of so many mistakes made by having the wrong information. So clearly we need to get rid of the paper-based system, be electronic in all our hospitals and the doctors' offices and so on. But even then some of your information is at your GP. Some is at the dentist. Some is at the lab. Some is at the hospital. Some is at the chiropractor. Spread all over the place. The natural hub for it is you. We believe in health records by the individual for the individual. You're the natural hub. You should own all your information. You should have all your information. That's one reason why I'm so excited about the Microsoft Health Vault project. I think that's outstanding. So Gordon actually went and did this. He went right now you have to request it in writing. It's a big hassle. He requested. He got all his records and scanned them and sent them all in. He's taking some data points and plotted them in Excel and tracked things. One of the universities that we funded, University of Pittsburgh, said, hey, this is interesting in its own right. What would it be like if you're doing MyLifeBits, we want to do MyHealthBits and work on a system for storing health bits personally. But let's go beyond that. The patient health records are electronic. You've got a copy. Good. But we can do more. Already you can go to Phillips and get a blood pressure cuff, a scale, a blood oxymeter, what have you, a number of devices in your home that will wirelessly talk to a hub in the home that I think in their system dials up and sends stuff to your doctor. You imagine you can send it to your health vault or do any number of things with that information. You could have wearable systems. We have body bugs that are tracking our heat flux and tell us our calories and the number of steps that we take. There's lots of smart materials coming out. Eventually you'll just put on your clothing and that will be tracking things. I saw a neat demo of some fabric at Dublin City University that would track the PH of your sweat and let you know when you're getting too dehydrated. And then when I talked to medical people about this and were telling them ideas in the book, they said, yeah, but, look, if you want to get the good stuff, you've got to go in the body. So the final frontier, the exciting part of these sensors that eventually there will be things in seeing what's going on with our blood, tracking what's going on with all kinds of vital signs. And the leading edge of this is implants people are already getting. So Gordon's pacemaker, for example, can wirelessly talk, is it induction or something, but anyhow, it can communicate with the outside world and tell the scoop on what's going on inside. The payoff for health e-memories is enormous. First of all, like this thing about those blotches. You know, think how many times you go to the doctor: When did you start having this fever, do you think? Oh, I don't know. I think maybe I got a little hot on Thursday. Maybe. No, it's going to all change. You walk in here's the graph of my temperature. Here's my blood pressure reading that I've been taking every night. Here's my weight. Real quantitative health. Solid values. It turns out also that there's a huge problem with people taking their medication. Apparently we're all really terrible at it unless it's pain medication. In which case we've got a built in incentive to take it. But otherwise people don't take it very well. But studies have shown if you can see the impact, if you can see your blood pressure going down over time, you're more likely to take your blood pressure medication. We can discover correlations in your life, what leads to illnesses or different values going the wrong way. Eventually having electronic nurses that will proactively come in and say, hey, this is kind of trending the wrong way, let me give you some tips. You could even interact, be some interesting prototypes in this space. Now, of course, electronic nurse will never be the same as a real nurse. But, on the other hand, while there's some disadvantages and some advantages, too, because people don't feel the same reticence about opening up about entirely everything that's going on to an Avatar, it turns out, compared to a real nurse, you might hold back a little bit. And, finally, anonymous data sharing. If we can anonymas a bit of this information being collected and do expert systems on it, we can look for all kinds of stuff. I gave this talk at Xerox Park, had a guy come up to me at the end, he said I was one of Ed Feigenbaum's early students and we had these really early lame expert systems and we applied it to not much data and we found all these drug interaction problems. And he was super -- he said this blows my mind. If we had this much data and modern expert systems, it's unbelievable what we'll be able to turn up. Moving on from health, how about your everyday life and after life? I was working on my notebook in a restaurant one day and I couldn't help but overhear these two old ladies talk to each other. And one says don't call and leave a message on my home phone because you can't. Call my cell phone instead, because the home phone, all messages are all, full. It's all my grandson; I don't want to delete it. Isn't that the nature, it's not that she wants the transcript of his words, she wants to hear his darling voice. We want that special connection. And we like recording that increased fidelity to have that richer storytelling. And some people have said, oh, you cold, heartless guys, you talk about shredding all your stuff and digitizing. That's so cold and techie. I said, hey, you may say that but while your physical mementos are up in the attic collecting dust, mine are on my screen saver enjoying them. Who is cold and heartless. I'm having a good time with them all the time. Yours are where you'll never see them probably again. And it's amazing the level at which you connect to them. This is a time line visualization of pictures of Gordon's son. And on the bottom is the distribution in time of the shots. And I look at it and I go, okay, that's a distribution. But Gordon looked at it. He said to me, "Yeah, it drops off here because he went to college. There's a spike there. That was the family reunion. Picks up again because that's when the grandkids are born so we took lots more pictures with them." I went, wow, even here a histogram is telling a story to him. Even the data has a story in it. Take our locations. Here's -- some of my kids play hockey. I went down to southern California for a hockey tournament. I have my GPS with me. Here, the pink lines show where I went and the red dots show where I took pictures. And so there we are down at the beach, and here we are back up at the hotel. And since you being in a place a number of times the lines make a big mess up on each other, we can pick a particular trip and animate it. You can see the blue line showing as I drove up the highway. I got home after the weekend. I loaded this up. I saw this. I went wow, I've got this. I would have just said trip to LA and had a few photos, if I bothered to even say that. Now I've got the distinction between these little dots up here, I've got the distinction between the hotel, the Starbucks around the corner and the rink, which I would never have done on my own. Also, I have my calendar which is full of when all the games were. I thought if I could just roll this up and send it to my mom, she'd finally think I'm a good son who tells her what's going on with her grandchildren and I wouldn't have to do any work. That was interesting enough we actually hired an intern worked on this for a summer doing automatic blogging. You take all your stuff from your calendar, you say maybe these few shots are lame, or I leave out these and let it roll and away you go and you get a blog from it. So we talked about automatically capturing things, Web pages, pictures. If you're going to automatically capture, you've got to think also about automatic summarization. So think of a SenseCam. Now you're getting three to 4,000 photos a day. Wow. And, by the way, you can't look for the clusters of photos, it's just all photos. Well, Dublin City University, who we funded, they took it and started working on event segmentation based on they looked at faces. They looked at clothing patches. They said what do we see that's different. Took the accelerometer from the SenseCam, looked for patterns of activity. Using GPSs also, so they had location. They said, okay, if I wanted to summarize my day, what am I looking for? Their idea was let's look for novelty. If I'm having breakfast and it detects I'm at home looking across at the same old face, that's pretty boring. It's pretty usual. But if I'm out for breakfast somewhere, that's novel. Probably more interesting moment of your day. They stitched together a visual diary of the day and the boring breakfast ends up being a little thing in the corner and things they think are novel, they just make bigger. Mouse over, you get that time lapse view of whatever the event is and they're segmenting by event. Nice automatic summarization. Now the ultimate summary will have to come when you pass away and somebody gets your life bits and they go, wow, what is all this stuff, right? But there's some interesting angles to maybe even what you might consider digital immortality for total recall. I had lunch with Ed Feigenbaum down at Stanford, who is called the Father of Expert Systems. And he drew this on a napkin for me. He said, yeah, Jim, when we started we thought it would look like this. We'd have a bunch of logic and data and we'd do this reasoning and good stuff would come out. But the insight that we eventually gained is that it looks more like this. What we want is lots and lots of data and we really want to keep it simple. I say, wow, what have we got with total recall. Lots and lots of data. So even with Einstein and what he left behind, Carnegie Mellon lets you go to a virtual Einstein and ask questions you get answers based on his writing and biographies and whatnot. A company called mycybertwin.com took the transcripts from the Simpson scripts and you can talk to Bart. What do you think of your dad, Bart? My dad Homer got a chess set once, packed it away, when I asked him why, he said he was saving it for a brainy day. Do you have a pet? Who needs a pet when I have Homer. I have Santa's little helper, too; he's a dog. The scripts are nothing when you think of a lifetime recorded with everything you say, the phrases you tend to use, the facts about your life. Seems likely that we could do a pretty good job of simulating you when you're gone. And think about what it would be like if you could ask your great-grandfather questions, what was it like when you met great grandma, things like that. So total recall is coming. We think it's inevitable and it's going to shake up society, like we talk about the Industrial Revolution and other shakeups to our society. It's going to change it just as much. And like these other revolutions, these changes, some of them are just change. Some of them we view as bugs that need to be fixed. Some are just change. For example, we have automobiles. There's a bug that there's pollution coming out of them. But, on the other hand, the fact that I can commute a number of miles every day to work, that's just a change to our society or the transportation is different so I can get fresh vegetables in the wintertime. But we do have to face up to a lot. Actually, a journalist recently said to me, he said, "What are the problems that might stop this?" I said, no, no it's inevitable. It's coming. There are problems but it's coming anyhow. I said it would be kind of like back when cars first came out, they'd say those automobiles, they're smelly and they're noisy and they scare the horses. Right? There were problems. But it wasn't going to stop them. The same way we have problems we have to face. Here's a bug for you. When ACM 97 came out, we put it on the Web because we were interested in telepresence at the time, telepresentations. And within a few years someone emailed me to say, hey, there's an audio file you've got, I can't play it anymore. And I checked out with our media team up here and I said let's get that codec posted so they can play it. They looked into it and said, Jim, actually we had a license from this company. The license expired. The company is bankrupt. It's in receivership. There's no hope -- it's illegal for us to let you play that clip now. So we have to watch out. Here's Gordon's flight of fancy poor, lost and forlorn data saying dear application, why have you abandoned me? We all know this, too, you have these formats that go stale. So there's a challenge here. I think there's a real opportunity. I mean, the ultimate in this is that we have virtual systems that can run every past software and hardware environment. In between that, the services they can roll things forward to formats that are still usable. And i think anybody who offers a back-up service should have a freshener service that goes along with it that keeps things fresh. In the meantime, we try to go for what we call the golden formats, formats we think will survive. My rule of thumb, if more than ten million people are using it, there should always be a market for keeping it usable somehow. Privacy. Boy, this is a big one. But already if you don't behave yourself on your next date, gentlemen, you could end up on dontdatehim.com. We all know stories n the YouTube videos out there and surveillance cameras all over the place. But when we talk about audio/video recording in particular in relationship to total recall, there are some serious privacy issues here. But I would argue that we've maybe crossed the line already for all the problems you think you're going to have you already have. And I looked to the experiment by Steve Mann that I think demonstrates this. So Steve gets a group of people and they'll wear t-shirts like this that say for your protection the video may be recorded and transmitted. You can't see well here but this is sort of that smokey glass here, so there might be a camera behind it. You don't know. Or else they wear the bulb that looks like a surveillance camera on it. And you might -- so they call it the "MaybeCam." You might be recorded. Steve likes to do this because he wears this recording apparatus all the time. He's been really hassled by people. And he gets mad when he says, you're hassling me, but you've got all these surveillance cameras up. So fair is fair. Anyhow, so his big thing is to go into someplace with a lot of cameras wearing these things and watch everyone freak out. The interesting point that I want to make here, though, is even if no one actually has a camera, you will get the same reaction. You don't have to be recorded for it to change things, just maybe be recorded to change things. And I would submit to you that we are already there. I mean, besides the amount of surveillance that's out there that may be recording you already, if people want to do it personally, you can already go online and get a little USB stick that has a pinhole camera in it that would record a number of hours of video. Microphones are so easy to conceal. Cell phones could be rolling. You don't know. In fact, it's interesting, with the SenseCam, I went into a deli one time. It was around my neck. And I walked up, and I'm buying the stuff. The girl behind the counter said, is that a camera? I thought, uhoh, maybe is this one of the moments where it's like shut the camera off. And I said yeah. She said oh, and kept going. Because she presumed that I would have to hold it up and go click, click, click to take her picture. But actually I took three or four pictures of her while I was in there. You never know. Then legally will my electronic memories testify against me? What's going to happen here? Could this be a downside where I get called into court and have to bring these things back up. So one idea that's floated is maybe we get some wrong on purpose. If we inject some fake pictures and put some wrong locations in and stuff like that, then maybe the court won't be able to admit it. Sounded good but a lot of legal people said no that's not going to fly. Maybe we can work on that. We'll change our laws. I'm all in favor of this. I think that this should be treated more as like an extension of our biological memories than some kind of piece of paper that can be subpoenaed. And it's interesting. There was a case where someone was trying to be compelled to court -- the authorities wanted to compel and hand over an encryption key to decrypt his drive. And the judge said no, you can't do that. That's like testifying against yourself. Now it's being appealed now. We'll see where it goes. But already our laws are starting to grapple with this and say what does this mean. Another example is where some have offered the opinion, hey, look, if you're going to go after this stuff, all right, but we already make a distinction between saying, hey, let me see your papers and I'm going to strip search you. There's a higher standard needed for strip search. It ought to be at least like that, ought to be an increasingly high standard. So some movement in the law, some discussion. In the book we suggest how about we put it in a Swiss data bank. Now whenever I say that, the people go, yeah, but the Swiss are having to hand things over like they didn't used to. I'm talking about how Swiss banks used to be. And the idea is it's the anonymous. It's the deniable place to store things. And if you think about technologically there's a number of approaches we could have here. Imagine a peer-to-peer system where you don't know what you're storing even. You don't know who it's coming from. It's all encrypted. You never see what it is. Things like that. There ought to be ways for us just at least to take the sensitive parts that we have and lock them down and keep them safe. And, by the way, maybe even have -- you know, in the spy movies, when the spy has the code word. He's called up. He says a certain word, then they know he's compromised and they all bug out. They should have that, too, where if I go to my Swiss data bank and I give the special password, it goes, oh, the stuff over here in this folder, shred. Right? So here's another time line like the one I showed you before. This is my Web pages. And in the middle here this big blank spot in the data distribution is where my hard drive crashed after four months of not backing it up. And until that day I thought, well, it's kind of fun recording my Web pages. Like it's sort of cool. But the day it happened, I got surprised. I got really emotional. I was upset like; my memories have been lost. And after that I would start hunting for things, and I couldn't find them. I go that was in the four months that I lost. I realized I crossed the line from this is kind of fun, it's a novelty, to I count on it. I expect this is what life is like. It's like I wouldn't buy a house without flush toilets why would I want to have a browser that doesn't record every Web page. That's how my attitude has shifted on it. And that's kind of how our attitudes have shifted on what we thought was just a crazy experiment with electronic memories. We think that -- today we talk about prehistory. Like before there was writing. It doesn't even count. Eventually you're going to talk about pretotal recall. All those poor humans with pathetically documented lives that lived back in the 20th century as the electronic memory revolution changes everything. Thank you. [applause] Now, questions. Go ahead. >>: This idea is about filtering. But is there things for prioritizing things to get through the deluge? Because what I'm seeing is the impact of just too much data makes people [indiscernible] and actually lose focus on all of it. >> Jim Gemmell: Right. Absolutely. If you have too much data you suffer from clutter -- by the way, I forgot, remember the picture of Gordon, the big pile of books? Part of that was to talk about clutter. One thing is, first of all, we feel incredibly decluttered by going digital. We're able to get rid of so much paper and our offices are tidier, incredible feeling of liberation that the computer is remembering for me and I don't have to worry. But the good point about clutter, and Gordon came in part way through the project and he said: I got too many Web pages and a lot of them are practically the same thing and I'm getting cluttered. He said I need a delete button. I said, hang on, not necessarily a delete button. Instead we had an intern come in and do a near duplicate similarity detection. And then we just took the near duplicates and can shuffle them away. Voila. Now you're down to what you want. There's a number of automatic thresholds. For one thing we can also -- we had a little thumbs up button at the top. We can say this is explicitly interesting. But besides that, another useful threshold we had, remember we were tracking the window that was in the foreground, the time and the activity. We could look at the Web pages that you engaged with and a really good heuristic I found when I was looking for pages would be say eliminate anything that I spent less than ten seconds on. And that gets rid of a whole bunch of pages, too. And remember the Dublin City University example looking for novelty and things like that. Again, these are some examples. There's a lot more. It's a great challenge to Microsoft. We have to deal with quantity and get rid of clutter. But one final thing, Gordon has the suggestion of the cloaking function. >> Gordon Bell: Right. >> Jim Gemmell: Tell them about that. >> Gordon Bell: I had proposed it. I can't get it anywhere. I also proposed it to Apple so that we can copy it. >> Jim Gemmell: See, if we don't listen to him pretty quick, you never know where he might go. >> Gordon Bell: But anyway, the basic function is because you do get a lot of things as you're moving along. And in the event that you find something that you're looking for something by location. Generally you look for things two ways, two principal ways. Where it might be and what the content is. So you're trying to get, usually trying to get something by content, basically, or, quote, searching it. But in the event that you have to go into a folder or something and there's a lot of stuff there that's old and you know that you're not going to use it in sort of that year, day-to-day, I want to cloak those. I want to cloak folders. For example, I've got folders for all of the financial -- I've got a folder per year every year in my main -- whoops -- that's in my main kind of let's call it my business folder. And I'd like to cloak all those, because I know I'm not going to -- it's unlikely I'm going to use them, but in fact I want them there. I don't want to get rid of anything. Oh, that's the other thing. You had a talk here about delete. How many of you were at the delete talk? Anyway, we don't believe any of that, by the way. I listened to the talk, too. Jim, I couldn't get Jim to listen to it. >> Jim Gemmell: I won't take it seriously enough. I guess my initial response to it even would be: Anything you would have deleted you could cloak. You could hide it away and say don't return it to me unless I specifically -- you could have a second level of really lock it down. Even put on external drive and unplug it and stick it in the closet. But you never know the value that you're going to find. I would like, for my cloaking, I have a folder just with bills. And as they age I would like them to automatically become cloaked unless I say otherwise. If you look at sort of a least-recently used principle. Because I don't want to have keep creating new folders by dates, I want to keep dumping ->> Gordon Bell: You had a good example of looking for an old bill because you were trying to find a vendor that had a guarantee on it. So you don't care about that bill this year because it's all -- you really care year by year because the Internal Revenue Service wants you to deal with things on a year-by-year basis, but then you're looking for a vendor three years, five years ago. >> Jim Gemmell: You go back to the cloaked stuff or archived something like that. Maybe we should move on. Another question. >>: So you talked about the challenges of media, broadcast media, all those sorts of things, which if you glance away, look at them, the parts you experienced you wanted to capture, is there a way to have an agent record for you on your behalf, rather than you having to record it, because many people are viewing the same TV show. I wonder if you started thinking about, rather than you capturing or acquiring all of those things and archiving them yourself, where you are ->> Jim Gemmell: Like TV shows and stuff? >>: Yeah, your attention -- >> Jim Gemmell: Well, actually, for those, in the end, I don't really have any interest in capturing them, because more and more -- I mean, I'm virtually certain 10 years from now I'll just go online and whatever TV show I want to see or movie I want to watch again it's just going to be there. Really, it's more about logging what I do. Which is really interesting, by the way. I'd like the system to learn even with my personal media. Oh, when that photo comes up on my screen saver I always skip it or when it comes up at a certain time of day or something like that I'd like it to learn from my patterns. >> Gordon Bell: But you have to have the equivalent of thumbnails there. In fact, we just had lunch with co-conspirator on this, Roger Litter. He said I'm recording lots of video now, I have eight terabytes of video, and I calculated high -- he had maybe 800 movies that he may want -- he said I record these movies or these shows if I think I might want them. But you need the equivalent of thumbnails or something that lets you go ->> Jim Gemmell: Again, he's overwhelmed by the size of his collection. He needs a recommender system. He said I wish I had even random clips pop up to me to help suggest things. Let's take a question here. >>: Interesting you bring up the [indiscernible] right now. But I had questions more about the social aspect of total recall, especially since I've been living in [indiscernible] taken photos -- taken photos, but I have. And then I have noticed most people, even sometimes I do myself, when you're aware of being recorded, they do change a little bit, you might say. And even at Microsoft, [indiscernible] a person, when you don't want that physical there. Have you noticed people, when you are carrying your life bits or sensor camera, whatever it's called, do they censor, change their behavior somewhat? >> Jim Gemmell: In principle, you're absolutely right. I think people are more sensitive to audio, though, so the pictures as not as big a deal. But when you record audio, they really start self-censoring, I think the best example are politics. Politicians are the leading edge of people who are recorded all the time. What have they found? I better not say anything off-the-cuff. All you'll ever hear from me are scripted banal totally boring, safe stuff. And that is the risk. And I'm glad you brought that up, because in the context of total recall, we're saying some aspect of it is inevitable and it's coming. The continuous AV is least interesting to us. I like it for holidays or birthday parties or things like that. But what I'm really excited about is having a record of everything I read, of giving students the ability to record all their educational experiences, of giving information workers the ability to record all the kind of information that they deal with and have that at their fingertips and use it. Of enabling all the health data to make us healthier, things down the line there. And the last thing, and the least thing, is the continuos AV. That said, the technology is there. And you're right, it does make you behave different. And my point with the "MaybeCam" is even being maybe recorded will change your behavior. Another question back here. >>: I'd like to follow on that. So at least very anecdotally, so n of 1, the scenario where I want the audio, in particular, maybe the video, and maybe there's a sort of DVR, somebody said I was supposed to get something when I'm here at the grocery store and I don't remember what those things were. And I want to be able to roll time back to that or mark this thing as important and that level of explicitness, the save button phenomenon, I think, you're right, there's a nightmare associated with that. But making all of it archived and saying, oh, we don't think the audio and video are that important; it feels like that's kind of on a collision course of itself. Again, anecdotally, I know. >> Jim Gemmell: I have a couple of things to say about that. What's the thing you learned about the belt? Deja view. There was this deja view camera, recording video on a continuous loop like a 90-second buffer. If you pushed the buffer, it would say the past 90 seconds is interesting, keep it. It's another interesting model where you're not necessarily intimidating people that you're recording everything. And you could maybe have a little flash to go off to say I just kept the past and they know. The other part of it, though, is you want to be reminded. And I think there's some great products. We love a product called REQALL. If I want a reminder, if I think of a good idea while I'm driving, I call REQALL on my phone and I say add. I say what I want to remember. You could say buy milk on Tuesday. Tuesday you get a reminder. You can say I need to buy milk when I'm at the grocery store. >> Gordon Bell: He's not trying to make that work with GPS so you're in the grocery store and it says. >> Jim Gemmell: When you're at a location you get that reminder. >> Gordon Bell: It says you've got to get ->> Jim Gemmell: It has the here and now reminders. >>: I see pieces of this vision happen already. >> Jim Gemmell: Oh, yeah. >>: [indiscernible]. >> Gordon Bell: Should be. It's happening all -- that's one of the points of all this, too, that in fact you are doing it. We realize we're doing it. I don't know. I personally believe it is the trajectory for the personal computer. What is the personal computer all about? It's this. It's your surrogate memory. And that's what we're all engaged in. >> Jim Gemmell: We were afraid the book would come out too late. Since we released it in September, iPod nano said they're recording video in steps. Samsung has come out with a new GPS enhanced camera. I mean, this is moving rapidly. >>: My question is -- bought in a full lifestyle. My question is, do you think people are going to go there, or will you see some small start-ups, little pieces? >> Jim Gemmell: Little pieces, absolutely. Which is already happening. >> Gordon Bell: But it's step-by-step. >> Jim Gemmell: And you get -- so we mentioned REQALL. There's another product Evernote. You can snap pictures with your phone. .it will do OCR on it. So health alone. So talk about little pieces. Some people will say I want improved health. They'll use the Health Vault and record more stuff, wear the devices. Someone else will say I want that digital photo record. I'm going to go crazy with my photos, want to have the management for it. Different people enter at different points. Ultimately, though, it's all going to spread and build. And one thing that we learned there's a lot of power of bringing things together for us to be able to say things like when was it on that hot day? What happened the same day as I emailed. Right now we have too much in different silos, and it's a real challenge to Microsoft to help us integrate across the silos and use the correlations between them to give us real power. >>: What type of work can be done to look at monopolization? For example, you give a point in time. Someone else, were you there a week ago, and trying to put together interesting parts or multiple people having multiple views of the same type of event. Because right now you talk about it as an individual, but it's interesting to say [indiscernible] everybody else and put that together. >> Gordon Bell: I'd say we didn't consider that. And within -- it's come up. Some of the things, when you look at Facebook, there may be something there. There's a source of other content that's going there. I don't really know how you sort of fuse this stuff together, because one of the things is really keeping a lot of this private in terms of that's what you're doing. >> Jim Gemmell: But if I could interject there, though. I think for public moments, so a couple of scenarios I think would be great to take advantage of. So say you're at a family gathering. All you need is the one person of that bent. I won't say anal. But the person who wants to comment and mark it up, make it pretty for us all to take advantage. Or another example, imagine -- so I mention I'm a hockey dad. Here's what I would love is I go to the rink, I watch my kid play. There's cameras all over the rink and they're recording the game. I go home and of course I fast forward to where my kid made a good play and I mark that. And in fact maybe I don't mark it. Maybe the system notes I watched it 17 times. At the end of the season, the system just looks at it says here's all the bits that people watched a whole bunch of time and right now you see somebody generally goes and spends 97 hours constructing the indices and video. We could just do that automatically. And, plus, you could do more. So I might have said a comment, I might have said great goal or I said things about it. We could share. And so yeah there's a lot we can gain out of sharing. We didn't work on that. Let me add, this book is not about the work that we did. Again, we only got a little sliver of this. But we got enough, we see where it's going. This book is about the future. It's about where we're heading. I think it's important for all of us. It's a revolution that I think we need to come to grips with. I'll take your question. >>: Two questions. As it stands today, as you start life blogging, what kind of software is commercially available for organizing and parsing data that we can capture, video or images or text or whatever? And the second one is, is Microsoft pioneering any of this revolution, other teams at Microsoft planning to implement software like you talk about? For example, I've tried using Health Vault, but it doesn't come anywhere close to myHealthBits. Doesn't ->> Gordon Bell: Right. You can't upload images. >>: It's very basic, almost laughable. >> Gordon Bell: Well, one of the things, there's a chapter with 10 start-ups in there of things that can come. And so the idea was really to stimulate within this environment. We just think that that's -- again, it's inevitability, and that's really what's happening. And as you guys become aware of this is what you're really -we think this is what you're really doing here or this is what we're all about. Unless you're working on databases for genomes or something that's in another particular application domain but anything around personal computing, this is it. This is where we're going. >> Jim Gemmell: By the way, is Microsoft innovating? When we started, there was no desktop search. >> Gordon Bell: Right. >> Jim Gemmell: Gordon sent a memo saying we need desktop search and their answer was: Why would anybody want that? [laughter]. >> Gordon Bell: And, furthermore, I said and, by the way, here's the company that we ought to buy. And ->> Jim Gemmell: But we didn't. >> Gordon Bell: And actually Steve Sonofsky, I think Jim Gray had to intercede and say, really, Gordon's okay; he's just very intense when he wants something, he goes after it. >> Jim Gemmell: Another question here? >>: When you accumulate all the data, obviously one of the core things is to relive your life, right, it's not just to recall, it's reliving moments as well. Are people really looking into what it takes to relive moments and post data? Has anybody really thought about that? >> Jim Gemmell: Well, the dimensions you can push of it. Higher def video. And research demos of smell playback and things like that. >>: Prompted by what she mentioned earlier and what you actually mentioned, like maybe I take my part in a restaurant, it would be nice to have context of what created the memory and that's a very complex question. >> Jim Gemmell: What's funny, though, is that the way things are going is in these areas that we don't think of a memory. We would think our senses, I'd like high-fi video and audio and surround sound and smells stuff like this and instead we're getting temperature and humidity, what's the RPM of your car and how many loads did you do in your washer. It's not playing out exactly how we might expect. But there's some real power in it to help you find things to say I'm looking for the stuff to happen on the day when I did all that laundry. >>: Something like organizing the stuff in your MyLifeBits about how many big hits it gets. How many [indiscernible] like because you would say this part in my life is close to what I already know, this piece is not. This piece is more uniquely me versus something that's close to what I already know about. >> Jim Gemmell: So showing -- that would be sort of what's the stuff that I have that's secret. That would be the stuff that what haven't I revealed. >>: Or what you have that's already known to the greater Internet. >> Jim Gemmell: Interesting. Okay. Interesting suggestion. We'll take another one here. >>: This is a pragmatic question. If you have everything collected in, let's say, one place and there's specific scenarios you've been working on X, at Microsoft, and then now you move to join Y, Google, what happens to all this ->> Gordon Bell: Ha, that's one of the challenges. >> Jim Gemmell: That's in the book. >> Gordon Bell: That's the lobotomy problem. [laughter] and, in fact, unlike some of the people, I don't know what you guys do, but Jim Gray and Jim Gemmell and I certainly have the one memory. We said life is too complicated already. We can only have one memory. And so things are also always crossing over. Gee, that's a professional thing. And then, oh, then there's going to be a committee meeting on this topic and we just can't separate those things. And so there may be some service that as you leave LCA, the legal guys say, well, we will give you your lobotomy. >> Jim Gemmell: Hand over this part of your brain. And we discussed this at some more length in the book. One point I'll just mention from what we say in the book also is the enforcement side of it will always be on what you reveal. Because no one will actually ever be able to police what you keep. So the question is, even if you're supposed to give it up, will that be observed any more than the posted speed limit on a deserted stretch of highway. Over here. >>: So the video is still 100 years of life and everything like that. Some people believe like rate Kurzweil well, we're just about into infinity in life, similarity is upon us. Are you thinking about those sort of potential things and extending biology so we live to 300 years old and how do we capture that amount of data, and what does all that mean? And how do we not become like the board. >> Jim Gemmell: The media -- [laughter]. >> Gordon Bell: The media problem is enough for all of this. We're worried about how do you keep data 100 years. I think that's more of our concern right this minute in terms of how are we going to make that data available over a couple of generations. Although, if we look at the paper version of that, yeah, after a generation or two people, anything that you might have kept gets thrown -- a couple generations, gets thrown out. So maybe these bits will get thrown out. But we in principle we want to make the bits as good as paper, which that's a challenge for you guys. That's a challenge for us all. >> Jim Gemmell: By the way, feel free to leave here. Looks like we're going on and on. That's a great challenge at Microsoft, imagine people coming, saying I would like to pay for a service to keep my bits for 100 years, how would we do it. That's a great challenge. >>: Move to book signing. >> Jim Gemmell: Move to book signing and come around to the book table and we'll talk to you while we do that, too. >>: Up here. >> Jim Gemmell: Up here. >>: If you don't mind. >> Jim Gemmell: Okay.