Inaugural CSCW Lasting Impact Award

advertisement

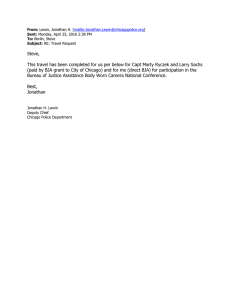

Inaugural CSCW Lasting Impact Award >> Andy Wilson: Okay, so thank you all for coming. This is going to be a fun little event. This is basically to celebrate Jonathan Grudin's winning of the first ever CSCW Lasting Impact Award. >> [applause] >> Andy Wilson: Yeah, that's right. So the conference is next weekend in Baltimore and he's going to be giving this talk in front of the conference and so this is a bit of rehearsal. So the paper is thus, Why CSCW applications fail: problems in the design and evaluation of organizational interfaces. And we're going to hear about that, we're going to find out why it was selected I think. And learn about some of the context and the history of this work. We're going to do something a little bit different so we have a discussant, an ATIT style discussant today. So we have a guest of honor, his name is Steve Poltrock. And he's coming in today. So just a little about him and then I'm going to let Steve introduce Jonathan, in this very complex proceedings today. So Steve is a Seattle native. Born and raised in Seattle. He got his bachelor of science at Caltech, a Masters in math at UCLA and then got his PhD in experimental psychology at UW. And in 1977 he became a professor at the University of Denver. I believe you were there for a period of several years, is that right? >> Steven Poltrock: Five years. >> Andy Wilson: Five years. And then in 1982 you joined Bell Labs and I think that's where he met Sue Dumais if I'm not mistaken. And then he met Jonathan when he was working at MCC in Austin Texas. And then at this point he had sort of transformed himself into a kind of a psychologist will been a little bit away from the engineering side of things. And then in 1989 he headed back to Seattle and worked at Boeing and eventually became a technical fellow at Boeing, and a long and distinguished career of 20 years at Boeing. And today he's retired, but he's come out of retirement today to help us through this paper and provide some historical context and commentary. And he will be giving a short presentation after Jonathan's, but first you're going to introduce Jonathan. Thank you. >> Steven Poltrock: Thank you. So this is an odd position to be in, introducing Jonathan to a group who all probably know him quite well. But I met Jonathan in 1986 when he came to work for MCC, a place I'd been working for, for about a year it at that point and we worked together for a couple years. When he left to go to Europe I left to come to Boeing and I was delighted when he returned to Seattle so that we could continue to work together although we were working for different companies. This paper is one that he was working on while, when he came to MCC and started working on it before even coming there and so I had an abundant opportunity to talk to him about it beforehand and it really changed my life, this paper and working with Jonathan. And so I'm going to be delighted to talk after he does about the impact that I think this papers had. So with that, I'll turn it over the Jonathan to present this work. >> Jonathan Grudin: Thank you Steve and thank you for coming to this practice talk. So as Steve said, I'll talk for a while, he will then set some of the context and perhaps say something about the impact that I would be too modest to say and if he doesn't say enough, I might overcome my modesty and add a little bit. And then maybe at the end, I'll say a little bit about how, what guidance it might give to, or what's happened to since 1988 and this particular paper's impact that might be relevant today. So this paper was unusual. It didn't have, it didn't build on the existing literature. There was no system building, there was no usability study, there was no formal experiment. There was actually no quantitative data. The qualitative data in it was not coded and the paper did not build on theory but. So why was it written and what did it say? Okay so in 1983, I left a cognitive psychology postdoc in England and returned to working as a computer programmer which had been before graduate school. The reason being, I wanted to build things and felt like we could build things quickly. At that time in 1983 there were single-user killer apps such as spreadsheets and word processors. We decided to build killer apps that would support millions of small groups out there. And I worked on several applications and features to support groups. We solved the technical problems and they failed in the marketplace. So the question was why was group support so hard to get right. >> Audience: Wait, that's you? >> Jonathan Grudin: Yeah, that's was me, sorry. >> [laughter] >> Jonathan Grudin: That was me at the time of this work, right. So it was a while it ago. >> [inaudible] >> Jonathan Grudin: That was my passport photo, that's the only photo I had from that period. So in the summer, after several failures in the summer of 1986 I quit and actually spent the summer going over our experiences of the last few years. And I wrote the first draft of this paper and with my colleague Carrie Ehrlich, wrote a draft of another paper on fitting usability the software development processes. Carrie Ehrlich was also a cogno psychologist. Her father was a tech company executive and I learned about organizations from Carrie and it changed my life, so I've put her picture up there. Then after the summer was over I needed to work again, I took the job at MCC where I met Steve and when I arrived I heard about a conference that was being held in the company auditorium. It was the first CSCW conference and I asked, what is CSCW. I attended the conference and realized that my work belonged at this work and it belonged at that conference. And so, I owe a thanks also to Irene Greif who just retired from IBM for pulling together CSCW in 1986 or 1984 actually. Because her impact in bringing together, and bringing together CSCW far outweighs the impact of anyone CSCW paper. If it weren't for CSCW, I probably, this paper and I probably would note that the impact that I did. So thank you Irene. Okay so my research at MCC for the three years that we were there followed, actually followed the path of the two summer papers. Understanding group support and development practices for building interactive software. Steve and I got some informal training on ethnography and social science from Ed Hutchens of UCSD and from Karen Holtzblatt who was then at digital and was just then developing contextual inquiry. And of course Steve and I began this collaboration that has been very productive partnership through the present day. He's more or less in retirement, so there he is. You've seen him. Okay, the CSCW 88 paper was directly responsible for all the jobs that I've had and visiting professorships that I've had since then and so what I'll do now is cover the main points of the paper and what it said and again why it was written. Okay so as I had said before, I had spent years working on these unsuccessful group support projects and so the questions were, why weren't automated meeting scheduling features used, why weren't speech and natural language applications adopted. Why didn't distributed expertise location and distributive project management applications thrive? And the paper used examples to illustrate three factors committing to these problems. So point 1 is that if you consider a project management application that requires individual contributors to update their status, the manager is a direct beneficiary of using this application and everyone else has to do more work and individual contributors who don't see any benefit in it often don't. And I thought that this must've been written, at the time, I thought this must've been written about. I talked to friends who worked elsewhere in other companies and in universities and they knew of nothing about it. I also didn't find any relevant history when I went searching in the Boston Public Library. And later I realized that mainframe computers, which are really the dominant computers even at that point, had been so expensive that employees were mandated to use applications that came along. But now, with many computers and workstations and PCs coming along, individual contributors were not typically mandated to use productivity tools. And so that was perhaps why it hadn't appeared in the literature before then. And this first point is still relevant, so for example the example for a project dashboard can motivate and does motivate internal wiki enterprise projects, but again encounters the same problems. Which is individual contributors who might use a wiki for their own purposes, typically don't use it to update their own status. And really don't want to use it for that purpose. So point two is that managers usually decide what to build, what to buy and what to do research on. And what we found is that managers who had very good intuition about individual productivity tools, regularly failed to see the point one. They failed to see the problems or challenges that an application might create for the other users of that application. They could see the benefits for themselves, so for example audio features, really speech and audio really appeal to managers who used dictaphone's and didn't know how to type. But of course for the recipients of an audio message, find it a lot harder to browse and understand and reuse audio as opposed to typing. And in my estimation it's based on some analysis. Hundreds of billions of dollars have actually been squandered over time in cases such as these. And it's still happening. Point three here is that you can learn from someone being brought into a lab and using a word processor, a singleuser application for an hour, but you can't learn much by bringing in a half a dozen people to a lab and saying for the next hour you are an office workgroup. And this may seem, I see people nodding and this may seem obvious now, but back then we were trained to do formal lab experiments. I mean we were scientists, right? Even today you can find many published studies in which three or four students are brought into a room and asked to be a workgroup for a period of time and I think very little results have questionable usefulness in most cases. Other than maybe as pointers to things to look at more broadly. So when I wrote this paper, the first draft of it emphasized point two. Maybe because I was struggling in organizations with managers who were making these decisions, but I talked to a friend, former colleague UCSD, Don Gentner, advised me to switch the order of the first two items. And I did it, and he was right. Here's a picture of Don. Academics who are starting to come into this field don't work in strongly hierarchical organizations and they just don't resonate with management issues. And I think the same is generally true in industry and research labs as well. So I think that was an emphasis on the first of those three items turned out to be significant. Now why did the paper have impact? I think Steve will talk a little bit more about the sequence, but I think there are a few factors. One is, it really arrived at the right time. So in 1984, my friends and I had been on the leading edge of work in this area, but in 1988 more people were grappling with group support. Secondly, it was presented early in a large single track conference, and several of the subsequent speech speakers referred back to it and my former advisor Don Norman who was giving the closing keynote address also called out this paper. And Don has been a fairly strong, has reminded people about this paper over the years, so I think he gets a little of the credit for its ongoing impact. And then the third factor here is that I built on that paper. I expanded the set of factors from 3 to 5 to 8 as I read about other researchers work that was relevant. In particular Lynne Markus and Lucy Suchman's work. So they also get some of the responsibility for how this work developed. Now I'd like to summarize this and then turn it over to Steve after which I may have a few words of counsel based on more recent experiences. So summarizing, in 1986 I really wanted to get the word out fast so that developers could avoid beating their heads against the same wall that I had been. In conferences back then like the CSCW 88 conferences were not archival. The proceedings, there was no digital library, the proceedings were only accessed typically by people who had actually attended the conference. Also conferences were attended by people industry, not academics. There were very few academics than, almost none studying CSCW and not even many studying human computer interaction. So my only goal in writing the paper was to inform colleagues at Wang laboratories, at Digital Equipment Corporation, at IBM and elsewhere. And because the proceedings were not archived, I assumed that the impact would last for months, maybe a year. After which the people who I knew who were working on CSCW would have absorbed the points and moved on. And it also, it didn't matter to me if my observations were original or not. You know, I would've loved, I didn't find anything in the literature, I would have loved to cite something relevant in the literature, but even if I had found something in the literature, I would have wanted to get the word out because I had come across it and neither had all of the other people I knew working in this area coming across it. And the point was to say them these headaches. And they didn't actually plan to do anything more with the paper after presenting it, but then a journal editor asked to reprint it. A book editor asked me to write a chapter based on it and I eventually expanded it into a communications ACM paper which is actually been cited more than the original conference paper. Okay so as the slide indicates, thanks to Moore's law and related legislation, there are several ways that we can contribute. We can invent the future by building unimagined devices, we can improve existing processes and there's still wicked problems out there and you can have a lasting impact if you tackle one of those. Last Friday, if you were here for Harry Strum's talk, he said that people in MSR would benefit from spending a year or two in product development groups. And in 1983 that was exactly what I did post PhD and it completely inspired and completely shaped my future research. So this problem was motivated by a problem in practice that did not come out of an idea for a new product or an unresolved question in the literature or theory driven hypothesis. Okay, so with that I will turn this over to Steve. >> Steven Poltrock: Okay, so it's a pleasure to be invited to talk about this work. I'm going to start by sort of setting the context. What was it like in 1988, what was the state of the field in 1988, in both CHI and CSCW? In terms of personal computing, which would be the foundation for collaborative technology, consider that in 77 Apple came out with the Apple II, the PC emerged in 81. 88 was when Windows version 2 came out, so we're not even talking about PCs with reasonable networking capabilities prior to that date. We're really at the infancy of the capability. Networks were really primitive in those days, it was difficult to connect computers together. He didn't have domain name services for example and in terms of conferences, the first CHI conference was in 82, so we're only six years after the first CHI conference and the first CSCW conference was in Austin Texas at MCC. So 88 was the second conference because they were only every other year when this paper came out. And this paper came out in 88 but it was a piece of work that he had been working on for the two years prior to that time. So it was during this time when it came, he had an unusual opportunity at Wang, working on on this kind of groupware system because others just weren't there yet to a very large extent. So these were really some early observations. Now if we look at 1988, what were people thinking about, what were the research topics? Well, one hot topic was, should menus be linear or should they beat pie shaped? I mean these were the kind of things people were grappling with. How should you transfer between one menu system and another? And my favorite is, the data model is the heart of interface design. That's where we ought to be focusing when we're trying to make the user interface work for people, instead of thinking of the user as being the heart of interface design. These are a summary of some of the major papers at CHI 88. There was some also, some CSCW papers. There are topics, there was a panel in two papers that address CSCW issues. The first one there was a study of the coordinator which was a system developed by Terry Winograd and his graduate student that for office work and it turned out to be hated by many people and so it was an analysis of what was going wrong there. Then there was a panel in fact that Jonathan organized to talk about the problems of user acceptance of groupware and Irene Greif and others participated. And then there was a paper about a group support, a meeting support system essentially for a facilitator. How a facilitator could use this software to help run meetings. So that was sort of a state-of-the-art at the time this paper emerged. Now we were both at MCC, and it was of research consortion that had been founded by the major computer manufacturers in America in response to the threat of the Japanese fifth generation computing effort. There was a fear that Japan would do for computing, what it had done already for automobiles. Essentially taking over the business in the world of automobiles. We've had a resurgence in automobiles, but people were afraid that computing would all move to Japan. It didn't work out that way. I don't think that was because of our magnificent work, but what we were expecting to do was to be kind of the group that was going to blaze the trail and look five, 10 years ahead and determine what computing should be like in the United States. And the topics that we were focused on were four groups. One was natural language interfaces. One was intelligent UIMS's. One was 3-D graphic interfaces, and in fact I was leading that group when Jonathan arrived at MCC, and the fourth was intelligent user assistance. So these are topics that there's still some interest in some of these. They're still ongoing work in these topics. So maybe we're more than 10 years ahead because it's been more than 25 years since then. But Jonathan came in with some new ideas and the ideas were based around this paper and a new group was formed called organizational interfaces. We had thought a lot about a name for it and Computer Supported Cooperative Work did not come up, but organizational interfaces and it's sort of theme was radically different. All these other groups were focusing on building some kind of new technology that would move us beyond where we had been. But the thesis, the premise that Jonathan came with was that the problem facing us in this field is not really that much of a technology problem. People can develop it. If they know what to do, they can develop it to a very large extent. The real big problem was organizational and social. And organizational and social both in the development groups and in the potential user of those groups. And in fact that's what, I became a true believer, I started working with Jonathan on this. I went off and studied with him large development groups and I finally came to Boeing. Why? Not because Boeing is a great developer of groupware technology, but for a company like Boeing using collaboration technology is absolutely essential. And so I got to be involved in trying to deal with this from a user community perspective. So let's look at the impact of this paper. First, the digital library alone tells us that this paper has been downloaded more than 6000 times. It's been cited within papers published in the digital library itself, 266 times. And the average papers cited 14 times, so it's quite a big number. Google scholar said it's been cited over a 1000 times, and it's the third most cited CSCW conference paper in the digital library, according to Tom Finholt. Jonathan mentioned that he expanded this work. He started off with these three basic problems and expanded it to a larger set, and that was published in communication to the ACM, and that expanded paper has been downloaded more than 6000 times and cited more than 1500 times. So quantitatively the impact has been large on people's thinking. This is a chart that I got from Tom Finholt that shows the number of citations by cumulative, by year. Four of the papers presented in 1988, just the papers at 1988 CSCW, and the green line is Jonathan's paper. So you can see it far outstrips all the others. This other paper here is by Bob Kraut and the others are all much lower than that. And the key thing is really that their cumulative citations kind of tapers off while these two papers really continue to grow at a rapid rate. See can see the point here is that this work is still having an impact. Its impact has not gone away after all these years. Now what the paper does is lay out three challenges with some examples. And Jonathan's already gone over them. The first one is the disparity between who does the work and who gets the benefit and he illustrated that challenge by talking about online calendars and why they have not been successful. And talking about group decision support systems. The systems used to support meetings, face-to-face meetings, and talking about digitized voice applications. And in each of these cases talking about the problem of, you know someone being asked to do some work that doesn't get benefit for and those people declining to do that work and then the system fails. He also talked about the breakdown of intuitive decision-making. Now he focused really on, oh when there were two principal applications there. Project management applications where management could really see it would be great if everyone use this, and they just couldn't get it ready to do it. And then natural language interfaces, shared databases. Now I should say that it's not really the case that these individual applications work only, essentially what he did is, consider all of these as problems for each application, but I'm sort of categorizing them where the greatest emphasis was. And the last one is, Jonathan discussed was the underestimated difficulty of evaluating these applications. So with that said, I'm going to now look at these and say, what's been the impact of each of these, because the reason this paper continues to be, have such a big impact is because each of these defines a separate thread of research if you will, and people working in those different threads keep coming back and citing this paper. And in fact every one of the lines I had previously, there's all thread of research that's emerged about it. So we take the first one, more work with no added benefit, I would say there have been more citations about this than any other one thing. This is been a problem that people keep running into. They do not find a solution for it, and so I just quoted three papers all published in just the last two years that continue to talk about this. One saying the CSCW community is already familiar with the idea that organizational culture and structure determine how or whether a new technology may be adopted. And Grudin states that every additional effort to put into a collaborative tool should have direct value for it's users. And important work by scholars like Grudin describe the world in which application failures, activity systems and infrastructures lived within larger systems of interaction that ran all the way up and down from fine-grained details of design in practice to the exigencies of law, institutions and other mechanisms for the large-scale organization of collective choice and power. More work with no added benefit in addition, Hooper and Dix published a paper just last year and had quite a long piece to say about this in which they gave Jonathan some substantial credit here. Looking back before web science or even the web itself, Jonathan Grudin's classic analysis of groupware includes issues of critical mass and what would now be called network effects which would not look out of place in web science setting. Indeed it is not surprising that Grudin's work was the inspiration for an analysis in the 90s and for the potential for CSCW applications on the web. Another one of the topics of the paper and expanded on it some length was online calendars, and I'd say it's probably not been a paper published about online calendars since then that hasn't cited this paper. And I list some of them here, I should note that some of these were written by Jonathan and or Leysia Palen who worked with Jonathan, so no surprise that they would cite themselves. But this last one for example, in 2012 there's continuing work by other people in this area that are citing this paper. The problem of the breakdown of intuitive decision-making. A recent paper, Sarah Keesler among other authors wrote top management did not consider technology and technology integration to be an essential solution to organizational issues, citing this paper. So management continues to be a big problem here with not getting what's needed to get technology to be successfully adopted. And there have been a number of papers that have essentially said, well let's see how are we going to solve this problem. And so they propose something like using consultants, mediators, frameworks and I list three papers here that took that problem, those approaches. I note that this problem is not really limited the management. This is a problem of there being a difficulty with intuitions about how collaboration is going to work. And in the days when Jonathan wrote this paper, management was going to decide what programs got written and how they were structured what they did, but now today I'm sure at Microsoft, a lot of these decisions are being made by developers. And so they are also able to have bad intuitions. Essentially they're going to intuit what seems right for them. Now my own personal experience, having worked for years with NetMeeting coming from Microsoft, the NetMeeting kept getting thrown around from one group of developers to the next, each one of which would think, well gee, I would like to use it for this purpose. And we at Boeing were saying, please think about the way we're trying to use it without being able to get that message through very effectively. And the final big problem was the difficulty in studying group behavior in this too of course is an ongoing problem. There haven't been so many papers in just the last couple of years, but you can see here a long list of different proposals about using cognitive walk-through, usability inspections, all sorts of different ways of trying to tackle this problem. So the papers had a profound effect in many different ways. One consequence I think is that this paper is really at the heart of what CSCW is about, and one way of seeing that is a paper titled Six degrees of Jonathan Grudin, or at least that was part of its title that was published at, or presented at CSCW in 2004 if I remember correctly. And it included a social network analysis of all the publications in 1982 through 2003. And in that analysis, the most central researcher, the most central author in the entire field was Jonathan Grudin. I think an acknowledgment of this contribution. And that's it for me Jonathan, back to you. >> Jonathan Grudin: Okay well thank you. I don't think I have to add anything there. I will say just a couple points. Eric Horbitz suggested I give this presentation here and say what doesn't no longer apply from the paper, and a few things I was reminded of there. One is, a number of the examples, the last point, the third point about groupware being hard for group support systems being hard to evaluate. As Steve said, that's pretty widely seen now. And practically everything has features to support social activity. Some of the examples aren't quite so relevant. And one interest ring one is the meeting scheduler feature, automatic meeting scheduling which wasn't used in the 80s and I said probably wouldn't be because individual contributors weren't mandated to use it. And then before I worked here, I came here and give a talk at Microsoft in the early 90s and discovered that meeting scheduling was being used. And I then went down and gave a talk at Sun Microsystems and discovered the same thing. So it was a little embarrassing because I had said it probably wasn't going to happen, but then Leysia then, so then the question was why, what happened. And because there was two possibilities. One was people had published papers saying that the way you'd get this through was by mandating that individual contributors keep their calendars online, which is why it wasn't used before. Individual contributors typically preferred paper calendars. They didn't have that many meetings. And the other possibility was that you actually built in features that individuals liked into calendars and get them to use. So Leysia Palen, my graduate student ended up turning that, who was doing an internship here when I visited on different topics. She ended up making that her PhD work and what we did find was that in fact they had built-in features that individual contributors loved. And the feature, the feature that was overwhelmingly popular to individual computers was the meeting reminder. That didn't exist before, and individuals who didn't have many meetings would work through, past the meeting and not know what had happened. And once that came in, in these new calendar systems, individual contributor started to keep their calendars online for that. Yeah. >> Audience: So the tipping point in terms of like people having computers at their own desk and being on all the time, or had that already been the case before then? >> Jonathan Grudin: Well I think at Microsoft and Sun, it had probably already been the case before that, so. And it really was, and at Boeing too where we looked at it with Steve. So it was really, it was interesting. But as far as the basic CSCW work, that wrapped up, not too long before I came to Microsoft. And when I came here I didn't really change my basic approach. I'd like to say a little bit about how that works today, both maybe here but also in the larger CHI CSCW community. So while I was here I published a couple dozen papers with my managers and [indiscernible], but meanwhile unanticipated problems and environment surfaced that seemed interesting. And I'll say Microsoft research has just been terrific and given me the freedom to go out and explore those, pursue those problems and figure out what was going on there. So if citation is a measure of impact, it seems to be the main we've got , then my greatest success after the CSCW papers was my work here on personas design that I did with John Pruitt who was then in the Windows group. And that's approaching 1000 citations out there. I didn't invent personas, but I worked with John it. And in my opinion it was central to the second issue that I have in 1986 which was what design methods work for developing interactive commercial software. After that my next most cited MSR work was a paper on multiple monitors, and that completely was a set of observations. Was based on the fact that when I got here, and got multiple monitors I was very frustrated with the fact that we didn't design for multi-mon. So it was not even part of the design consideration as to how this stuff would work if you had two monitors. And so a lot of them exploited opportunities there. Similarly problems I encountered in reviewing for conferences and journals lead to papers that I wrote in analyzing where these problems arose in computer science. Lead to papers in communications to ACM and elsewhere as well as some experiments with new approaches there. My two favorite completed Microsoft projects while I've been here, also originated in workplace problems. One was the threat, some of you who have been around for a while may remember, or maybe do not remember that there was a threat of forced email deletion on employees that came out here. I worked on that for a while with Sue Dumais. And the second one was the monocia expertise recruitment, serious game that I worked on that was inspired by requests that we got from senior Microsoft consultants. And so the good news is that Microsoft let me do this stuff. Now, however Microsoft is really about inventing the future, it's not really about solving problems in enterprise behavior. And so I think that to a large degree, this kind of work that's based on finding problems that have been out there for a while and addressing it is not really appreciated that much here. And it's not really welcomed in CHI and CSCW anymore. CHI and CSCW have moved from practice oriented, from being practice oriented conference to a more academic model. Many reviewers out there are now obsessed with building on the existing literature and creating theory or informing theory. And so, I'd say that a lot of reviewers are inclined now to throw out the baby if the bathwater temperature isn't to their liking. So a lot of this work has ended up that I've been doing since, has been ended up being published elsewhere. And so I think my concluding point there, and I'd be interested in your views on it, but I think you could if you want to have an impact, you could help solve, you could invent the future. And you could help solve real problems out there, but if you do then I think you should be prepared to find a new sparkling communication channel to communicate to the people who can use what you discover, which is what I had to do in 1988. So, thank you. >> [applause] >> Jonathan Grudin: Any questions, or comments, or disagreements? >> Audience: It's funny that you were talking about, earlier there was one line about getting into the enterprise basically and the difficulties of people actually going in context. One of the things that I am experiencing at this moment, right now with my email is trying to get access enterprising to do this research. Just throwing it back to you, perhaps the rest of the group going out into enterprises, what do you see is the best way to do that today? To get in context real data from actual people doing actual productivity work. >> Jonathan Grudin: Well, okay so we should talk about it, but a lot of our partners out there, and our major customers actually. So maybe your specific situation may be an issue here, but a lot of our partners and customers actually do, are pretty willing, to let us come in. Depends a little on the sensitivity to them of what you're studying. But I will say it's the case, that can be a little easier sometimes from academia because when I was down at UC Irvine before I came up here, I came to Microsoft and did research and at Sun Microsystems at the same time, on the same issue because we didn't have some of those. So it really does, I think it depends a good bit, but even here I worked with Steve at Boeing. So Boeing was a place that, I guess it helps of course if you've got your closest collaborator working there. >> Audience: At least at Boeing, there was a Microsoft person sort of full-time at Boeing who could facilitate setting up that kind of an arrangement. I imagine that still the case. >> Audience: It is, but I think we have a bit of a closing. One of the things that I've been hearing a lot, I mean it's honestly an ongoing problem. I am an ethnographer so, that kind of work, and this is not the first time we've had this problem. But there's almost a paranoia, proprietary secret and then do the lawyers get involved, and then it all goes downhill from there. >> Audience: Uh huh. This can happen. >> Jonathan Grudin: Yeah, and the legal side is sort of ramped up, hoping it is, it's true. >> Audience: So, can I make a suggestion? One of the things I've found. I ran the [indiscernible] program when we allowed customers to come in and put bugs to our clean array database, back then. And one of the things that we learned by working with them was exactly what you said, there has to be something in it for them. If it's about being able to guarantee that the system will work for their organization and their type of data, that was the way we managed to get them to share their data with this. So we could do the pad analysis we needed to do. >> Audience: And then from, so I'm the privacy manager for MSR, and most organizations now have some kind of privacy structure. But we are not legal, but we are friends with legal. And so one of my key roles here is to facilitate getting data from other product groups and also outside organizations. And so I work with other privacy people to convince them that there is a business case, you know what's in it for those and for us. Here are the parameters, the data, here's how we're going to protect it, here seller going to make sure that we are just not throwing it all around with people they just steal. And so it might be a matter of making connections with whatever those people are, whether they are within the groups themselves or in the regulatory space, but working with them to help you with negotiations. >> Jonathan Grudin: I think first this one quick comment which is that this isn't a typical organization, but I currently doing work with schools, K-12 schools and I'm not having, and I have great access there all. I will say that at the iPad schools, it's a little slower getting into those than it is the tablet PC schools, but even those you can get into. >> Steven Poltrock: If I could just comment on this from some long time spent at Boeing trying to make just the same things happen. They can break down for a number of reasons. And one can be issues of sensitivity or privacy. Another one can be just a manager who's not willing to let employees spend any time with you because they feel too much under pressure. And we had that experience. Pamela Heinz of Stanford was about to come up and do this great study on disseminated seven and disseminated seven management just freaked out because they, I mean they had been saying yes, yes, yes, yes and then they realize how far behind schedule they were going to be and they just got worried about that. And it's a shame because they had exactly the kind of problems we were anticipating they would have. >> [laughter] >> Audience: You mentioned early, I don't with all these circles, but you mentioned earlier it was lack of metrics. And has that changed except for complaints? Is there any metric that transcends enterprises, privacy issues, security that you can evaluate or devaluate improvements? >> Jonathan Grudin: So I think that metrics, that's perhaps a whole other talk, but in the CSCW social media area, the whole metrics is very difficult because a lot of the benefits when you get into supporting large group are extremely hard to measure. I mean, at Boeing they were constantly trying to determine even what seems like fairly metrics, but fairly simple things like how will video conferencing affect travel, you know. And it just turned out, and even at Boeing they could even do studies where you had distributor groups around the Puget Sound area and how if you set up videoconferencing between you know Everett and Renton, you would think that you could actually start to get strong metrics in this area and they couldn't. You know it was just extremely difficult. So that's a big topic and we now have a lot more data. You know there's a lot more data can be collected as more and more activity gets online. >> Audience: [indiscernible] >> Jonathan Grudin: Well, I mean you have to see patterns. I mean you go out there and you look at a number of these and you start to see patterns and there are logical, you know there are sort of logical patterns that seem to explain it, but yeah ultimately it's correlational, you know. It's very hard, it is hard to... >> Steven Poltrock: Simply looking at metrics when it's optional is a tremendous tool. You know, who decides to use the technology and when is just a tremendously insightful tool. >> Jonathan Grudin: And it's not just complaints, it's also the successes. You know I was sort of looking at like when calendar, you know when calendars did start to be used it was, I didn't know whether it would turn out that it was manage, you know that it was management mandate that people; I mean I kind of suspected that Microsoft managers probably weren't requiring it, but I wasn't at Microsoft at the time and didn't know. So you look at both the successes and the lack of update. Paul. >> Audience: Yeah, I love your ending comments that, I found it odd though too that these papers that we recognize as the fundamental ones of our field, you know that we recognize, they have this lasting impact that would not get in today. For the metrics that we use. And I think this has become a fairly universal problem among at lot of conferences. My suspicion has always been that this is intimately related to the expansion of publication requirements on academics. So could you say a few words about that? Where do you think we're going, what can we do about this in the future that, you know other than starting new conferences again from scratch. >> Jonathan Grudin: Yeah, well yes I do have opinions on this that are not necessarily correct or widely shared, but I think it is the case that academics, the conferences have become extremely academic. And even the industry tracks are often reviewed by academics. Industry design, you know attracts and other things at the conferences. So I think that that's part of the issue and then my own sort of red flag in this is that I think they have very high rejection rates. Before practitioners really wanted, who had a message that they wanted to get out there. When their rejection rates are so high, they could get the men because the conferences were more open in the early days and so you could get these things in. And they wanted to come and be heard and it's just very difficult now. And here the big change in CHI was, there were three years in the mid-2000's where the acceptance rate went down to 15 and 16%. And up until then a lot of product teams, a lot of user UX people in Microsoft used to submit papers and papers at CHI, and they just all, all the practitioner papers got leveled out and a lot of the user researchers switch to UPA which then started to have a peer reviewed paper track, because to pick up these papers that didn't make it into the ASIM comp. So it's a very complex issue and one that I would be more than happy to talk about again. >> Audience: Yeah, I have some questions. You said you know on using other outlets, I was wondering what those were. And another question was, you know I sort of share this concern that people are so preoccupied with getting published that they are chasing the sexy new things, new technologies, you know the first one to write a paper about whatever we're going to get cited more often, but they're ignoring like what are some of the core problems that we still have. You know, because it's not a sexy topic to write about. >> Jonathan Grudin: Right. >> Audience: And what do you think are some of those core problems that we still have that are not really been addressed because people are too busy chasing you know, too busy chasing the sexy stuff. >> Jonathan Grudin: So, there were a lot of questions there. As far as the new outlets go, I tend to look to you and others to tell me what new outlets although some of those are focused on the sexier issues. So I fixated on that particular. >> Audience: Well what are the core problems that you believe that warrant more attention but don't get it because people are chasing the sexy stuff. >> Jonathan Grudin: Well, , I mean I do have my list, but I think there are probably lots of problems out there that you could draw in. I think that from my perspective because I've had an enterprise focus, I think that one of the big changes, you know as Steve Ballmer was fond of saying, enterprise is 70% of Microsoft's sales and revenue, and 90% of it's profit and I think that in the last few years we've really had a big shift towards a consumer focus, whether it's competing with Apple and Google. And I think that's good and we've got to compete with them but I think we've left, there are lots of enterprise. They are our major customers and there are lots of issues in the enterprise space. Enterprise networking you know, is yammer, I mean what, you know is social networking and enterprise, how do you make that work. I don't think that we've quite figured that out, so I think that, and yet we've been trying for a long time, so I think that there are. So my list is a little bit more biased towards the enterprise side. K-12 though, I can also study now. I could tell you what some of the issues are in K-12, so. Happy to take that off-line, but I would just challenge you to look around at the problems that you run into and the problems that the people you talk with as users or here at colleagues. I think there's not a shortage of them. Andrew. >> Audience: So generally it's kind of hard to write a paper or get a paper accepted where it's fairly negative on some project you try to do but failed at. Because usually the response is, well you guys are just idiots, you should have done it this way. >> Jonathan Grudin: You're right. I've got those, you are idiots. Before you get your point, I just say because of blind, the wonders of blind reviewing, I have gotten multiple reviewers who have said, if you just read the work of Grudin, you would have known not to try this in the first place. >> [laughter] >> Jonathan Grudin: So anyway, as you were saying. >> Audience: That's pretty awesome because actually I wanted to ask the inverse which is, who in your sense of that paper like, who is the most resistant to your lesson and like what arguments were they using against it, against believing it? If anyone, like did you just come up and say well, the calendaring system doesn't work, everyone should just stop doing this forever and shut down that line of research, or were people still trying to say, well you know. >> Jonathan Grudin: Well happily not, in the case because they made it work. I think I tried to be, I mean I think even if you look at the paper I did say in it for that example, that you have to find ways to make it work for individuals, for all the group members. You know, I think that was the key point and it just, I just didn't personally didn't see how to do that. And I'd say that, you know one form of resistance to this work, pretty strong, very strong form in the early days was from a lot of the CHI people who felt that formal experiments were the only way to go , at reduction of science was only way to go and I probably should name names, but a very senior professor at Maryland was just outspoken on this issue. That this was completely the wrong way to go, and he still has I view and if you look at his user interface design books, you won't see this cited on the section on CSCW, so there was some resistance in some areas. >> Audience: [indiscernible] >> Jonathan Grudin: That's right, yeah that's right. And Mary. >> Audience: Playing the devils advocate, and this wasn't the main part of your dissertation, but this point that you have about, you know that CHI and CSCW are only pushing, work on inventing the future and on sexy new things. >> Jonathan Grudin: I never used the word sexy. >> [laughter] >> Audience: Someone used the word sexy. >> Jonathan Grudin: I said it was resistant to the type of work that I submit. And as a data point, I'll just say that I've had one in my last 16 papers submitted to CSCW or CHI that got in. Or maybe it was two. >> Audience: Well maybe this is a different situation I had, I mean I feel like I go to CHI and I see papers on still, I'm like, Fitt's Law. And I think, you know that is like the antithesis of sexy. I mean Fitt's Law is like the opposite of [indiscernible], exactly it's like taking things that already exist and optimizing them a tiny bit more. So I'm just not sure that I agree with your thesis that CHI doesn't have. >> Jonathan Grudin: I wasn't, no I completely agree, I completely agree with you. A classic way to get a paper into CHI, and there are people out there that do this rigorously is to take some paper that was published 10 years ago that say compared two different approaches and say that now we've got two orders of magnitude faster systems, we can go and we can come up with something that will outperform those two and get it published. And you've got the literature review, you've got it justified because there's past CHI papers on it. You just got this incremental improvement on, you know whether it's a Fitt's Law type of situation or not, and you can get it in. And you go and ask, you know I have asked after hearing papers like that, I've asked the person. You do a very rigorous experiment, you do a very rigorous analysis and you know, after one of them I said okay well I kind of see that this is an improvement but the field has sort of moved on. And we've kind of standardize on an approach here. You know, it's like a better form of ASCI, so I just don't see how we ever moved to actually getting that used. And the person says, I don't know. And I said, well what's the next step in this line of research? And the person said, there is no next step. We just thought that we could do this CHI paper, and you know I have to get back to finishing my PhD dissertation on something completely different. >> Audience: I think that's different than what you were saying because you were saying that only work about inventing new paradigms of computing is... >> Jonathan Grudin: No, also improving... >> Audience: You said about the kind of impact, about whether it's a small incremental impact or very, more large and... >> Jonathan Grudin: No, I was to say that what I think is hard to get in are problems that are really based on practice, you know. And a better form of Fitt's Law didn't originate very directly from... >> Audience: For example I mean I feel that every paper I seen out of IBM for the past decade has been about problems with practice and enterprise software deployed within IBM. I mean that's sort of all the people that ... >> Jonathan Grudin: No, I don't buy it. That's not my assessment of the IBM work and we can take that off line. I mean I think... >> Audience: I just think that if you made a comment like that in your position at CSCW, you should be prepared that people might push back on it. >> Jonathan Grudin: Good, good, okay. I will definitely make that comment. >> [laughter] >> Jonathan Grudin: Excuse me, but I will phrase it. Thank you Mary. I will phrase it in a slightly more, hopefully slightly more clear, clear form. So that if they want to, I mean I could be wrong, right. >> Audience: So back on the paper for a second. You guys talk a little bit about how management or developers that you knew on settled it don't really understand or seem to not be paying attention about how their... >> Steven Poltrock: No, they have bad intuitions. >> Audience: Bad intuitions and so, and just watching the decision-makers in this company perceive, I don't see them reading academic papers. And so I'm wondering if you could comment on whether or not you think writing an academic paper is the right way to address these problems. >> Steven Poltrock: Well we certainly made other efforts, the two of us by giving tutorials and other things to try to get this message out. In fact I was thinking about that in relation to this other issue, because in the early days of CHI, it was clearly aimed at both academicians and practitioners. There were a lot of practitioners, and they were there to learn what to do and they would take tutorials. >> Audience: So, what is it now though coming how do you get these results from the stakeholders. >> Steven Poltrock: I don't know. >> Audience: [indiscernible] and it does enter into the mainstream, you know like textbooks in schools. And you're like, if you are learning. >> Steven Poltrock: Takes a while. >> Audience: CSCW in school, then they enter the workforce. >> Steven Poltrock: It is an issue, I mean I saw this occur over and over again and then we ended up discussing it quite a bit. At Boeing where they would put in place a workflow management system or something that required people doing a fast, a whole new job, like two jobs instead of one. And the management thought, well this is great, we'll know exactly where everything is at every moment and you know, it's complete failure. Years of development time out the window because nobody would ever use it. >> Jonathan Grudin: So this may or may not, I don't know if I recommend this, and I don't know if it would still be true but one way that I, that this paper did get to management in some places, get communicated to management was that there were one or two major consultants out there. Some of the meeting consultants had actually came across this and would tell it to management. So I got hired as a consultant a couple times because there are few people out there, and Don Norman can actually also be helpful in that respect. Some consultants were definitely reading the papers, whether they still are not I don't know. >> Audience: Did management like hearing you telling they are wrong? >> Jonathan Grudin: Telling them, I can be a little more tactful. I mean I'll insult CSCW, but I won't necessarily insult. >> Audience: They probably don't read the papers. You probably presented a very logical and doable method. >> Jonathan Grudin: I think I can, so the fact is that the management issue which I thought was, which I lead with originally, I thought was the most important, and I still really think it's the most significant because managers are still important. I wrote another paper that just really unpacks that that I thought was as strong as the CSCW 88 paper, and it did not, it got rejected by CHI and it got rejected by CSCW. And I think that there is a way that you could, but I think that it could be and eventually got published at Hicks, but I think that it hasn't piled up thousands and hundreds of thousands of citations, but I do think that there are ways to explain that, that managers. But how to get an audience for them is potentially a different issue. And it's even gotten worse in some respects now, because now managers actually use technologies, which they didn't back in the 80s. You know they were not hands-on users. Now they are, so in some sense they have equally or even maybe more confidence in their intuitions. But what's really the case is that they use completely differently. And that's really what I found quite a bit in the research done here. If you look at the way managers and executives and individual contributors use technology, the feature, and we saw this at Boeing too. The features that one of those groups loves, another group will hate and vice versa. So there really are, because of the way they work, the pattern of their day, the structure of the activities is different. So I think it is, it's still a really big problem, but I don't know the answer to how you communicate it to managers. I don't know if even anybody around here has read the paper that analyzes that. >> Audience: One of my concerns is that a lot of people just don't take the time to read and it's like people, management especially, they tend to spend 90% of their time in Outlook. >> Audience: Well, they are reading in Outlook. They are. >> Jonathan Grudin: Send them an email message. >> Audience: They're not, not reading. They're reading differently. >> Audience: Okay, it's all, like a paragraph. >> Audience: Yeah, and that's sad. If we're concerned people are not reading, we should be clear what we're concerned about. That we're concerned about reading full-length papers. So, for the fact that they are spending 90% of their time in Outlook reading, it represents an opportunity. Do the paper, but recognize there's an opportunity to inject this insight into Outlook for lack of a better term. Because actually that is what most the people I reading, here. >> Audience: And I wonder if this research though, maybe we can be, maybe this is what you're getting to and you could be a bit more proactive about it. Because it seems like, you know we have people like Jonathan, here in the company as an amazing resource, and we should be learning a lot and you know, the people, the execs do come to us and ask about things. But I think it's because people don't think of having intuitions for machine learning if they're not familiar with the field. Whereas everyone has opinions, but they think well we're... >> Jonathan Grudin: Yeah, you're right. >> Audience: Especially if manager start using software, and I wonder if we could construct like a review board of sorts. You know from [indiscernible] has some of the best and most experienced people who could help, you know product groups as they are doing their findings. Kind of like printing... >> Audience: Maybe a larger issue is just having those, continuing you know on management but, go with that. The idea that management could have some kind of understanding of what their reports are actually doing. >> Audience: Aren't you a manager? >> Audience: Yeah well. >> [laughter] >> [indiscernible, talking over each other] >> Audience: Directly trying to get at like you know, here's somebody the company who's a decision-maker who's going to say that we're going to put out this next version of this groupware and it's going to work like X. You know, and they are making the call. Do they have the opportunity to review the kind of insights that are coming from this work, and then here's the thing, this might never even have been aware of it. And I feel like that's something that maybe we could. >> Audience: Yeah, it's just interesting listening to this discussion because, you know I've been working in the app world, and one of the things you see around that job with these much smaller scope things, pointing at [indiscernible], have analytics everywhere. And incredibly detailed telemetry. And I'm listening to this conversation and just thinking, wow wouldn't it be cool if it was possible for us to build in the appropriate metric measurements into those systems. So we wouldn't be guessing and we can actually start refining instead of these reports and these metrics and help people understand what is the philosophy of the experience. Am I getting more throughput through my system or less? And people, is there more common of load on people than there was previously. It would be fascinating to figure out how do you do that. >> Jonathan Grudin: I think you want to do it talking to Sam, finding a ethnographers. I think going back and forth between the quantitative and then some qualitative understanding for what it means at a higher level. >> Audience: Just FYI on that, that is happening to a great extent in office. But the ability to have accurate telemetry, the system is not designed for telemetry. The system is designed for, you know CPU load, right. So the data that are flowing through, naturally flowing through, are not research indicators. They're not designed as such. So it's a. >> Audience: So the reason why I'm interested is, I'm part of the new OSD, dead sciences group where our job is to try and figure out how do we each try to understand, to be able to apply every feature that we do rollup. So that's the reason why I'm kind of thinking from that standpoint. >> Jonathan Grudin: So the devil's advocate has another. >> Audience: In terms of impact, was asking how much improvement [indiscernible] has today. Like when Steve presented about your work, he was actually showing the CSCM article which actually had more impact in some sense. >> [indiscernible, talking over each other] >> Audience: But in the CSW article, arguably because it was less of an academic paper format and more of a magazine, for a slightly more general audience. And so by the same argument, I guess I'm curious you know to have the most impact that you are advising young students at CSW. Should they write 16 CSW papers and get one, or should is write a blog that has a short version of their [indiscernible]. You do that and why or why not. Like why do you continue to submit CSCW articles for rejection rather than just writing a blog? >> Jonathan Grudin: Yeah, a great question. I hate it when students ask that question. >> [laughter] >> Audience: That's a good point. >> Jonathan Grudin: Oh yeah, it's definitely a discussion that needs to be had. >> Audience: The article that you had written within Microsoft research, it seems that kind of activity is rewarded, and the blog is read. I mean take Dana Floyd's work for example. She in part publishes conference papers, but she writes a blog it's very popular and I think that, that the powers that be recognize that as a legitimate more of an impact. So I guess maybe we should all be switching to that model, or if you have a big enough. >> Jonathan Grudin: I don't think there's room for too many Dana's though, so. >> Audience: Maybe we should all be studying [indiscernible]. >> Jonathan Grudin: Yeah, no I think it would be great to have a discussion about this. >> Audience: Or books, I mean in book don't count at all for academicians. You know they don't add any points for them. >> Jonathan Grudin: Yeah even droll articles in our field are pretty. >> Andy Wilson: Well if there are no more questions, let's first of all give a round of thanks to Steve. >> [applause]