Quantitative Research Summary 1 John Z. Doe September 5, 2005 EDST 750

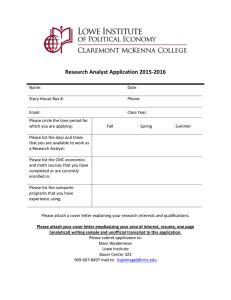

advertisement

Quantitative Research Summary 1 John Z. Doe September 5, 2005 EDST 750 Topic: Use of computer technology in the classroom Li, Q. (2002). Gender and computer-mediated communication: An exploration of elementary students’ mathematics and science learning. Journal of Computers in Mathematics and Science Teaching, 21(4), 341-359. Overview The primary focus of this study was to analyze the gender differences in communication patterns used by elementary students, while learning mathematics and science using computer-mediated communication (CMC). The secondary focus of the study was to examine student interaction related to gender differences, while using CMC to learn mathematics and science. The researchers wanted to assess the roll of CMC’s effects on the educational gender gap between females and males in a collaborative learning environment by evaluating messages created by students for length, generation, and the use of five language functions. Earlier research has revealed the advancements in CMC in creating a powerful learning tool for students, motivating students who have trouble adapting to learning in a traditional school setting, and assisting in the reduction of student gender gaps. The researchers want to determine the types of communication and interaction differences between student genders created by CMC. Research Questions The researcher’s of this study developed four questions to guide their experiment. The first was to determine whether male and female students differ in their use of five language functions in their messages. The second was to determine whether male and female students differ in their use of the five language functions in their initial message. These first two questions will be answered using analyzed data related to the five language functions. The third was to determine whether male and female student messages differ in terms of the length. The fourth was to determine whether male and female student messages differ in terms of the generation value. The third and fourth questions will be answered using data on message generation and length. Population The population of this study consisted of twenty-two students, eleven female and eleven male, from a Toronto, Ontario sixth-grade inner city elementary school. Each subject was a participant in the 1999-2000 “Knowledge Forum Knowledge Building Community Project”. Methods The data used for this study encompassed every electronic message from the populations mathematics and science courses. The Knowledge Forum Knowledge Building Community Project team recorded and provided all the data for analysis in electronic form. Each individual message from the data was analyzed for generation and the five language functions – asking information, giving information, making suggestions, presenting opinion, and expressing disbeliefs. The messages where marked according to whether the messages were independent or interactive, then assigned a generation value as defined by Henri*. The messages then where marked according their association with the five language functions. Each message having at least one sentence containing a match to one of the five language functions were marked as that language function. If a message contains the same language function multiple times that message is marked as that specific language function. If a message contains multiple language functions each language function used was marked. Each message was also measured for length by using T-units. This study states that a T-unit is defined as a main clause plus what ever subordinate clauses happen to be attached or embedded within it. A clause is defined by this study as one subject or one set of coordinate subject with one finite verb or one finite set of coordinate verbs with one finite verb or one finite set of coordinated verbs. Results Research questions number 1 and 2 were answered by using descriptive and inferential statistics on the data collected analyzing the five language functions. Male student messages contained the language function “presenting opinion” most often, while “asking information” was second. Also a third of the male messages contained the language function “giving explanation”. Of the female messages one-fifth contained the function “giving explanation”, while the most frequently used function is “asking information”. One the other hand, male messages presented the function “asking information” less than the female messages. Overall the most frequently used function was “asking information”, while the other four functions showed no statistical difference. Initial message data on the five language functions presented that on the average males have more “giving explanation” initial messages than do female students. Overall the statistical data on the other four language functions shows no significant difference. Study question three was answer by using T-units to measure the length of student messages. According to the averages, male student messages have few T-units, thus having shorter message lengths than female students. Study question four was answered by using a generation value. The research shows that the female students generation value is significantly lower than that of the male students. This leads the researchers to propose that females tend to initiate discussions more than male students. Implications This study found that in the realm of mathematics and science learning using CMC, that gender gaps still exist. Specifically, this data demonstrates that male students have a greater level of interactivity with CMC than do the female students. The researchers also found that the explanations and opinions of male students are more likely to be presented than suggestions; although female students are less likely to present opinions and explanations but more likely to request a significant amount of information. Also, the data shows that conversations are often initiated by female students through questions, and that male students more often enter the conversation after initiation. This data clearly show that female students communicate and interact with CMC in a significantly different way than to male students. Although it is evident that gender gaps do exist with online technology, this studied a small population group therefore does not represent a large enough data platform to significantly determine a concrete explanation of gender gaps. Further research, on a larger scale, must be done to not only determine the significance and cause of the gender gaps but to create a basis for creation of new computer based learning tools. * Henri, F. (1995). Distance learning and computer mediated communication: Interactive, quasi-interactive or monologue. In C. O’Malley (Ed.), Computer supported collaborative learning (NATO ASI series, pp. 145-161). Berlin: Springer-Verlag