Document 17852340

advertisement

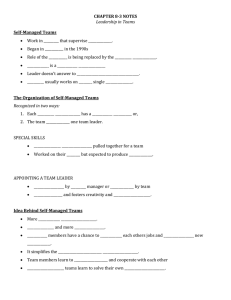

Attaran, M. & Nguyen, T.T. (1999). Succeeding with self-managed work teams Industrial Management, 41(4), 24-28. Abstract: Chevron's Western Production Business Unit established inter-functional work teams as a strategic approach to maximizing human resources in one of its profit centers. The company's goal was to foster teamwork, increase employee involvement, and cultivate employee empowerment. Chevron's experience is applicable to a wide variety of organizational settings, in both private and public sectors. Self-managed work teams are known by many different names: self-directed, self-maintaining, self-leading, and self-regulating work teams to name a few. No matter which name is used, by definition they are groups of employees who are responsible for a complete, self-contained package of responsibilities that relate either to a final product or an ongoing process. Team members possess a variety of technical skills and are encouraged to develop new ones to increase their versatility, flexibility, and value to the work team. The team is responsible for monitoring and reviewing the overall process or product (through performance scheduling and by inspecting the team's own work), as well as assigning problem-solving tasks to group members. The teams create a climate that fosters creativity and risk-taking, in which members listen to each other and feel free to put forth ideas without being criticized. From humble beginnings The concept of self-managed work teams is not new. They are a direct outgrowth of sociotechnical systems theory and design developed by Eric Trist and his colleagues in England four decades ago. The theory contends that organizations intimately combine people and technology in complex forms to produce outputs. This process is supported through sub-systems. The technical sub-system, for example, consists of the equipment, technologies, and methods of operations used to transform raw material into products or services. The social sub-system includes the work structure that causes people to interact with both technologies and each other. The primary means of implementing the sociotechnical systems approach has been crosssectional design teams, which usually implement planned change programs, initiate improvements, and encourage learning. The concept works only when team members understand their goals and are committed to achieving them. Therefore, team members are involved in formulating tasks so that they feel invested in the process and dedicated to accomplishing the stated goals. Figure 1 summarizes the major differences between traditional employee involvement and selfmanaged work teams. Self-managed work teams have become more common as the evolution of total quality management has continued. In fact, many companies consider such teams to be the productivity breakthrough of the 1990s. Quality and productivity have improved, turnover and absenteeism have been reduced, job classifications have been streamlined, and relationships with unions have improved (Figure 2). Approximately 20 percent of American employers used work teams in 1992, up from approximately only 5 percent in the early 1980s. This figure is expected to climb to 50 percent by the year 2000 (Harvey & Bowin, 1996). Chevron's jumping-off point The Kern River Asset Team is made up of 80 employees and is a part of Chevron's Western Production Business Unit and South Valley Profit Center. The team's main task is to produce oil from Chevron properties in Kern River Field in Bakersfield, Calif. Prior to 1995, the Kern River Asset Team was itself a profit center with many small asset teams spread over a wide area and with a traditional hierarchical organization (Figure 3). A number of philosophies on teamwork and employee involvement were in place, but they had little organizational structure to support them. Although the small asset team structure had helped to improve the work force, there were certain inherent problems: Because each asset team was responsible for all the work processes associated with the asset, it was difficult for teams to link those processes to broader objectives. Individuals also had trouble translating team ownership into daily activities. Furthermore, attendance at asset team meetings was not viewed as a core activity. Since individuals did not work together daily, they could not develop broader, big-picture knowledge of the processes they managed. As a result, individuals were left to make decisions without the synergy available from a process team. The small asset team structure promoted ownership at the micro level instead of at the macro level, resulting in duplication of work processes and poor utilization of resources. A new structure As a part of an organizational restructuring in early 1995, Kern River Profit Center was downsized to the Kern River Asset Team. Using this opportunity to their advantage, management proposed a new way to do business with more emphasis on process management. Specifically, the new selfmanaged work team design included (Figure 3): High-performance teams: Chevron's strategic direction called for organizing these teams around work processes and structuring them around quality improvement concepts. Employee empowerment: Management and employees realized that this concept implied joint responsibility by both management and non-management staff. Process improvement: An important lesson learned from the previous organizational structure was that operating costs were greatly reduced when teams focused on work processes. This lesson was integrated into the new self-managed work teams by having each team focus on a single process, taking time to fully understand it, and then identifying opportunities to improve it. A design team was formed to draw up plans for the selfmanaged work teams. Members were selected from every area that was affected by the reorganization. In addition, the design team included members of the steering committee to ensure improved communication and greater continuity (A consultant was also hired to oversee the process.) Through interviews and meetings with each existing group, the design team reviewed tasks from each functional and operational area and grouped related tasks together, which were then placed with newly designed process teams. Clearly defined boundaries were set for process-specific responsibilities for each group. The work force received regular updates throughout the design period. Eleven self-managed work teams were formed within the Kern River Asset Team organization (Figure 4). The five- to eight-member teams were balanced for technical expertise as well as social and leadership skills. After processes were fully flowcharted and measured, it was made clear that improvements were to be the core focus of each team and should not be viewed as outside activities. Once the new organization was in place, a training program for each team followed. During this phase, each team prioritized its tasks, grouped them into work processes, and most importantly, chose the ones on which to focus and to identify opportunities for improvement. Each process was then flowcharted to list suppliers and customers, and measured to provide a baseline for determining future productivity. The road to success Leadership support for the new organizational structure was provided by designating a coach for each team, who met regularly with a guidance team to monitor overall progress and effectiveness. The guidance team also acted as liaison between the teams and the business unit/profit center to ensure the center's requests were directed appropriately and handled properly. Team members (management and non-management alike) also needed education in basic skills such as team-building, problem-solving, communication, conflict resolution, and time management, as well as participation, responsibility, and empowerment. A training program was developed to address those needs. One immediate result was that, as skills in these areas improved, there was a corresponding improvement in product quality. It was clear from the beginning that the change to self-directed work teams would be an ongoing process. Each new team proceeded at its own pace according to its abilities and willingness to accept additional responsibilities. Ultimately, self-managed teams made most of the decisions that had been made previously by functional and operations supervisors. At the outset, each decision was agreed to by the coach and the team, but the longterm plan called for a transition of responsibility so that teams would handle all routine issues and rely on coaches only when faced with particularly complex or unusual problems. Bumps in the road Immediately after the transition to the new structure, frustrations and problems began to appear. These were due mainly to unfamiliarity with the new organization, new daily routines, and adjusting to limitations of duties imposed by the new plan's focus on specific (and process-related) team responsibilities. Other problems, however, appeared to have more to do with individual personality and behavior conflicts. Employees had to adjust to a working environment in which the new definition of teamwork required personal, cultural, and behavioral adjustments. Simply cooperating with peers and attending team meetings was no longer enough. Team members had to learn to put aside their differences in order to make decisions that would improve processes. Fortunately, the guidance team quickly recognized that the root of the problem was a lack of communication within the teams, and efforts were made to make the coaches aware of the situation. Finding a place The new self-managed work teams had to find ways to connect with the strategic intents set forth by Chevron's Business Unit. These strategic intents included (Figure 4): Adding more asset value than competitors had through exploration, development, and acquisition: Self-managed work team had the responsibility to develop projects internally and to prioritize those that generated the most benefit for the organization. To date, the economics of projects have, in fact, improved by decreasing the cycle times and by monitoring for efficient use of technologies funded by the asset team. Generating more profit per barrel than competitors: Process improvements are now part of the day-to-day responsibilities of the entire Kern River Asset Team work force. They are no longer considered additional, outside activities. With process measures linked to operating cost reports, teams use quality improvement tools to continually refine their knowledge and improve work processes. Ensuring that all business activities are fully compliant: Although all employees share accountability, a single selfdirected team manages and integrates all environmental activities for the Kern River Field. This team monitors environmental costs and views environmental issues as opportunities that can be managed to help create a competitive advantage. Conclusion Kern River Asset Team is the first work group of the Chevron Production Co. to re-engineer its organization with self-managed work teams. It will take several years before the transition to the new organization is complete. Early progress, however, indicates that the asset team is on the right track. Despite some early confusion, many process improvements have been initiated, such as: Chemical pump repair: Chemicals play a critical role in oil and water treatment processes. Injecting an inadequate amount of chemicals can cause problems in well gauging, water disposing, oil shipping, and other processes. In the old structure, the responsibility for pump maintenance was not clearly defined, which often left pumps in disrepair and resulted in under-injection of chemicals. The newly formed oil and water separation team resolved these problems by providing timely chemical pump maintenance and service. Sub-surface pump usage: Members of the well management team reviewed the process of well pulling and learned that sub-surface pumps do not need to be replaced every time wells are pulled for service. They revised the process by testing pumps prior to a pull job, enabling them to replace only pumps in need of repair. Although the amount of savings has not yet been determined, the new process has been significant in eliminating waste. Automatic well tester service: Members of the production analyst team are now taking charge of repair and service responsibilities that were previously handled by electricians and mechanics. This allows electricians and mechanics more time to handle other tasks. Many work groups are now looking at Kern River Asset Team as a model for the re-engineering process. Early successes have won over many skeptics who were doubtful about the viability of selfmanaging teams. The asset team realizes that some adjustments must still be made as the teams continue to mature and that in the next few years the teams may not look exactly as originally planned. Successful re-engineering of an organization with self-managing teams is not a quick fix. It requires a great deal of effort, commitment, and support from all members of the organization. In the long-term, however, the benefits to employee morale, efficiency, product quality, economic savings, and total quality management are well worth the growing pains. Cummings, T.G. and S. Srivastva, Management of Work: A Sociotechnical Systems Approach, University Associates, 1977. Davis, L.E., "Evolving alternative organizational designs: their STS-bases," Human Relations, 1977. Harvey, Don and Bob Bowin, Human Resource Management, Prentice-Hall, 1996. B Orsburn, J. D., E. Musselwhite, and J.H. Zenger, Self-Directed Work Teams: The New American Challenge, Irwin, 1990. B The Authors Mohsen Attaran is professor of management at California State University, Bakersfield, in the School of Business and Public Administration. He is the author or co-author of three books, more than 50 papers, and five commercial software packages. Attaran has conducted workshops and seminars for a number of private and governmental organizations. Tai T. Nguyen, M.B.A., is a petroleum engineer with South Valley Profit Center, Western Business Unit, Chevron U.S.A. Production Co.