CLiMB Center for Research on Information Access C

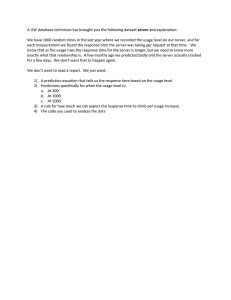

advertisement