Hierarchical Decomposition of Minimally Invasive Surgery:

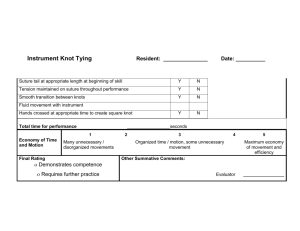

advertisement

Hierarchical Decomposition of Minimally Invasive Surgery: A Valuable Research and Investigative Tool MacKenzie, C.L., Ibbotson, J.A., Cao, C.G.L. & Lomax, A.J., Simon Fraser University, Canada Where is the surgeon looking? Analysis of gaze patterns: on the monitor, down on hands, away What surgical steps are difficult and take time? Note the time to wrap fundus is shortened when the short gastrics are cut Duration of Fundoplication Surgical Steps Duration (minutes) No Division 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 Divide Short Gastrics prepare patient divide peritoneum expose crura and EG junction repair crura divide short gastrics wrap fundus S urgical S tep What motions are performed most often during suturing? Reaching and orienting Frequency Total Number of Motions for Suturing (both tools) 18 16 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 normal suture 4. Results anchor suture reach & orient grasp & hold/cut push pull Reach and orient Slip grasper under release Lift Switch tool Grasp fundus Transfer grasp Grasp and hold / cut Pull across Insert endostitch Push Suture Pull Knot Release Cut suture Suture Knot Cut suture Motion Locate Prepare patient Divide Locate Divide Locate Expose crura and GE junction Divide peritoneum Join Locate Repair crura Divide Elevate Pull fundus esophagus under Divide short gastrics Anchor fundus Suture wrap Wrap fundus Close Nissen Fundoplication 1. Background 5. Discussion Complex activities break down to progressively smaller units Hierarchical decomposition can be used to: 1. Evaluate surgeons’ performance (Miller, Galanter & Pribram, 1960) Human factors, task analysis, user-task-tool 2. Design training for surgery e.g., with augmented or virtual environments Modular sections correspond to our procedural breakdown 2. Purpose 3. Evaluate surgeons’ learning 1. To study the surgeon as the user of the technology in a complex human-machine system 4. Design and evaluate effectiveness of new tools 5. Evaluate different aspects of O.R. layout e.g., monitor display position 2. To decompose minimally invasive surgery hierarchically 6. Preoperative planning of patient-specific surgery 3. Method 7. Analyze surgeons’ focus of attention at different levels of the hierarchy 8. Improve safety and decrease errors Videotape laparoscopic procedures: - cholecystectomies 9. Make a better “fit” between technology and the surgeon. (n = 4) - inguinal hernia repairs (n = 4) - Nissen fundoplications (n = 9) Define events e.g., tool entries, gaze shift, goal attainment Develop hierarchical decomposition Operationally define beginnings and endings of: - surgical steps - substeps - tasks - subtasks - tool motions Annotate videotapes and perform analyses on the timing of events. 6. References Cao, C.G.L., MacKenzie, C.L., Ibbotson, J.A., Turner, L.J., Blair, N.P. and Nagy, A.G. (1999). Hierarchical decomposition of laparoscopic procedures. In Westwood, J.D., Hoffman, H.M., Robb, R.A., & Stredney, D. (Eds.), The convergence of physical and informational technologies: Options for a new era in healthcare. (MMVR: 7). Amsterdam: IOS Press, 8389. Ibbotson, J.A., MacKenzie, C.L., Cao, C.G.L., and Lomax, A.J. (1999). Gaze patterns in laparoscopic surgery. In Westwood, J.D., et al. (Eds.) The convergence of physical and informational technologies: Options for a new era in healthcare. (MMVR: 7). Amsterdam: IOS Press, 154-160. MacKenzie, C.L., Ibbotson, J.A., Cao, C.G.L. and Lomax, A.J. (1998). Intelligent tools for minimally invasive surgery: Safety and error issues. In Proceedings of Enhancing patient safety and reducing errors in health care. Chicago: National Patient Safety Foundation, 226-229. Miller, G.A., Galanter, E., and Pribram, K.H. (1960). Plans and the structure of behavior. New York: Henry Holt and Co. Acknowledgements Thanks to the surgeons, O.R. staff, and patients. Thanks to E. Lee, S. Manske, and B. Zheng. Funded by British Columbia Health Research Foundation (BCHRF) and Institute for Robotics and Intelligent Systems (IRIS), Canada.