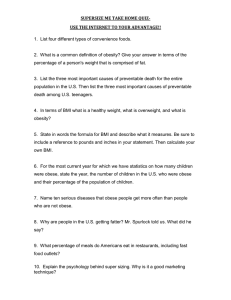

Supersize Me? Brian W. Zagol, M.D. Dan Dishmon, M.D. Department of Cardiology

advertisement

Supersize Me? Brian W. Zagol, M.D. Dan Dishmon, M.D. Department of Cardiology University of Tennessee The Good, the Fat, and the Ugly Introduction • We have all been taught that obesity is bad. • Movies, television, and magazines all preach that obesity in this country is an epidemic and that there are many health problems associated with its condition. • The medical literature also supports that obesity is a problem. Definition • Based upon observations by the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), the National Center for Heath Statistics defines the following: • • • • Underweight: BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 Normal weight: BMI 18.6 kg/m2 to 24.9 kg/m2 Overweight: BMI 25 kg/m2 to 29.9 kg/m2 Obese: BMI > 30 kg/m2 Introduction • Obesity has been implicated as a risk factor for the following medical conditions: - Decreased life expectancy Hypertension Hypercholesterolemia Diabetes Mellitus Gout Coronary disease Heart Failure Atrial fibrillation Stroke - Hepatobiliary Disease - Osteoarthritis - Cancer (esophogus, colon, rectum, liver, gallbladder, pancreas, kidney, non-Hodgkins lymphoma, multiple myeloma, stomach, prostate, endometrial, breast - Kidney Stones - Psychosocial disorders i.e. Lonely Saturday nights Relative Risk of All-cause Mortality and Cardiovascular Mortality Based upon Weight (Obese = BMI > 25) and Fitness Level Lee C D, et al. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999; 69:373. Relative Risk of Certain Conditions in Overweight Individuals (BMI>27.8) Age 20 to 44 years Age 45 to 74 years Age 20 to 74 years 5.6 1.9 2.9 2.1 1.1 1.5 3.8 2.1 2.9 Hypertension Hypercholesterolemia Diabetes Mellitus Van Itallie TB, et al. Ann Int Med. 1985; 103:983. Relative Risk of Certain Conditions as BMI Increases Dietz W H, et al. NEJM. 1999; 341:427. The Advantage of Obesity? • It is evident by large, observational studies that obesity contributes to a number of conditions which are known to lead to atherosclerotic disease and also to the development of coronary artery disease itself. • However once CAD has developed and these patients require revascularization, the picture is not as clear cut. In fact, FAT PEOPLE DO BETTER!!! The Obesity Paradox • In the 1980’s, the bias of both cardiologists and cardiothoracic surgeons persisted and overweight and obese patients were believed to carry a higher risk to revascularization than their non-overweight counterparts. • This bias persisted despite conflicting data on the subject. • The bias was so evident that an editorial in the Canadian Journal of Surgery, published in 1985 questioned whether obese patients should receive CABG surgery at all! Koshal A, et al. Can J Surg. 1985. 28:331. The Obesity Paradox • However, in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s retrospective analysis of large revascularization studies were finding surprising results in overweight and obese patients – they had fewer complications. • These results applied to both percutaneously revascularized patients and to those surgically revascularized. Percutaneous Complications • Obese patients undergoing coronary angiography would seemingly have higher procedural complication rates: • Difficulty gaining femoral arterial access • Difficulty achieving post-procedural hemostasis • Delayed recognition of vascular complications Percutaneous Complications • In an article by Nicholas Cox, et al. published in the American Journal of Cardiology in 2004, the group collected data on 5234 consecutive patients undergoing cardiac catheterization at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massacusetts as well as the Western Hospital in Fottscray, Victoria, Australia between January 2002 and July 2003. • They retrospectively looked at complication rates of those patients in comparison to their body mass indices. Cox N, et al. Am J Card. 2004; 94:1174. Percutaneous Complications • Cardiac catheterization was performed using standard methods with site of access determined by operator preference and patient suitability. • Obesity was defined as a BMI > 30kg/m2 • Vascular complications were defined as need for surgical repair, transfusion, the development of arteriovenous fistula, pseudoaneurism, or large hematoma (>8cm) Cox N, et al. Am J Card. 2004; 94:1174. Percutaneous Complications – Baseline Demographics Cox N, et al. Am J Card. 2004; 94:1174. Distribution of Patients Undergoing Catheterization by BMI Cox N, et al. Am J Card. 2004; 94:1174. Vascular Complication Rate Based Upon BMI Cox N, et al. Am J Card. 2004; 94:1174. Vascular Complications by Obesity Group Cox N, et al. Am J Card. 2004; 94:1174. Vascular Complications by BMI Looking at Approach Used Cox N, et al. Am J Card. 2004; 94:1174. Discussion • The authors of this study speculated that the lower rate of vascular complications seen in obese people may be accounted for by the following variables: • Obese patients have larger arterial size : sheath size ratio • Obese patients, at least in this study, more frequently received device closure. • The perceived increased risk of vascular complications in obese people may lead to increased diligence in vascular access and in obtaining hemostasis at the end of the procedure. Cox N, et al. Am J Card. 2004; 94:1174. Percutaneous Results • It is clear that overweight and obese patients have fewer complications from percutaneous cardiac interventions during the actual procedure, but how do they do long-term? • My colleague, I am sure, will point out that there are multiple studies associating increased restenosis rates in obese patients. • The medical literature documents that obesity, independent of blood pressure and diabetes status, is a risk factor for repeat target lesion revascularization, that some speculate is due to increased inflammation and insulin resistance. Percutaneous Results • However it appears with drug-eluting stents, the increased risk of restenosis may also no longer be a problem. • In a review of the data from the Taxus-IV trial, Eugenia Nikolsky, et al. published a study in the American Journal of Cardiology in March, 2005 looking at the impact of obesity on restenosis rates in the era of drug-eluting stents versus bare metal stents. Nikolsky E, et al. Am J Card. 2005; 95:709. Taxus-IV Baseline Characteristics Nikolsky E, et al. Am J Card. 2005; 95:709. Taxus-IV Clinical Outcomes at 1 Year Nikolsky E, et al. Am J Card. 2005; 95:709. Taxus-IV Freedom from TVR or MACE Nikolsky E, et al. Am J Card. 2005; 95:709. Taxus-IV Restenosis Rates Nikolsky E, et al. Am J Card. 2005; 95:709. CABG and Obesity • It is clear that obese patients undergoing percutaneous interventions have fewer periprocedural complications AND with the advent of drug-eluting stents increased restenosis rates no longer seem to be a problem. • But what about obese patients who require surgical revascularization? CABG – Procedural Results • Obesity is frequently cited as a risk factor for adverse outcomes with CABG surgery. • Nancy Birkmeyer, et al. in a study published in Circulation in 1998 prospectively looked at 11,101 consecutive patients undergoing CABG between 1992 and 1996 at medical centers in Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont. • Patients were categorized into the following groups: non-obese (BMI<30), obese (BMI 3136), and severely obese (BMI>36) and were evaluated for procedural and in-hospital complications. Birkmeyer N, et al. Circulation. 1998; 97:1689. CABG – Procedural Results Baseline Characteristics Birkmeyer N, et al. Circulation. 1998; 97:1689. CABG – Procedural Results Birkmeyer N, et al. Circulation. 1998; 97:1689. CABG – Procedural Results Conclusions • With the exception of sternal wound infections, the perception among clinicians that obesity predisposes to various post-operative complications is not supported by the data. • Furthermore, there is no difference in mortality among these patients and obesity seems to be protective on the risk of postoperative bleeding. CABG – Long-term Results • It appears safe to perform CABGs on obese patients, but how do they do in the long-term? • Luis Gruberg, et al. in The American Journal of Cardiology in February, 2005 analyzed the outcomes of coronary artery revascularization for patients with multi-vessel CAD based upon the data collected in the large ARTS trial (Arterial Revascularization Therapies Study). Gruberg L, et al. American Journal of Cardiology. 2005; 95:439. CABG – Long-term Results • The ARTS trial was a multicenter, randomized trial that compared PCI plus stenting with CABG in patients who had multi-vessel CAD. • A total of 1205 patients from 67 participating centers worldwide were enrolled between April 1997 and June 1998. • The obesity analysis was based upon the 3-year outcomes from this trial. Gruberg L, et al. American Journal of Cardiology. 2005; 95:439. CABG – Long-term Results Baseline Characteristics Gruberg L, et al. American Journal of Cardiology. 2005; 95:439. CABG – Long-term Results Gruberg L, et al. American Journal of Cardiology. 2005; 95:439. CABG – Long-term Results Kaplan-Meier Curve for Survival without MACE (Death, CVA, MI, or Repeat Revascularization) N.S. Gruberg L, et al. American Journal of Cardiology. 2005; 95:439. CABG – Long-term Results • In the ARTS registry, BMI had no effect on 3 year outcome of those who underwent stenting. • Conversely, among those who underwent CABG, those who were overweight or obese had significantly better outcomes than did those who had a normal BMI with regard to survival without MACE, mainly driven by decreased need for revascularization. Gruberg L, et al. American Journal of Cardiology. 2005; 95:439. Summary for the Obesity Paradox • Obese patients requiring revascularization procedures compared to their non-obese counterparts: • Have a lower procedural risk at cardiac catheterization. • Do not have increased rates of restenosis, since the advent of drug-eluting stents. • Have overall equal risk of undergoing surgical revascularization, with decreased periprocedural bleeding. • Have better long-term outcomes after undergoing CABG in regard to survival, free of major adverse cardiac events. • Bring on the Bacon!!! Paradox, Schmaradox Obesity is known to predispose patients to increased overall morbidity and mortality Obesity is associated with conventional cardiovascular risk factors such as HTN, DM, and HPL Furthermore, obesity is associated with endothelial dysfunction, insulin resistance, and inflammation that may contribute to the increased risk for adverse clinical outcomes Obesity and PCI Clinical outcome in the 1st year after coronary stenting is determined primarily by restenosis, manifested clinically as recurrent ischemia prompting repeat revascularization of the original target lesion (target lesion revascularization [TLR]) HTN and DM have been associated with an increased risk for TLR after coronary stent placement Any effect of obesity on TLR may be influenced by the increased prevalence of these obesity related diseases No Paradox Here Fat Needs No Friends These findings are consistent with an obesity effect that is not mediated by DM or HTN Insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction are independent predictors of early restenosis after coronary stenting Neointimal proliferation after stent implantation in patients with IGT has been shown to be greater than in patients with normal glucose tolerance Products of adipocytes include IL6, TNF-a, and CRP Inflammation has been implicated to play a central role in neointimal hyperplasia Correlation between levels of inflammatory markers and propensity for restenosis has also been demonstrated Previous reports of an obesity paradox after PCI are possibly explained by inadequate adjustment for high-risk patients at lower extremes of BMI and focus on mortality outcomes Obesity and CABG Obesity is often thought to be a risk factor for perioperative morbidity and mortality with cardiac surgery Factors predisposing and contributing to severity of CAD as well as the technical difficulties in surgical and postsurgical care of the obese likely contribute to these perceptions Many previous attempts to study the association between obesity and outcomes with cardiac surgery have suffered from limitations caused by sample size and lack of data about potential confounders In most studies, those classified as obese or severely obese were on average younger, more likely to be female, more likely to have other CAD risk factors, had a greater incidence of L main disease, and higher LVED pressure Patient Characteristics Birkmeyer, et al. Obesity and Risk of Adverse Outcomes Associated with CAB Surgery. Circulation. Morbidity of Obesity It has been demonstrated that obese patients undergoing cardiac surgery have a higher incidence of peri- and postoperative MI’s, arrhythmias, respiratory infections, infections of the leg donor site, and sternal dehiscence Post-CABG Morbidity in the Obese Pathophysiology Myocardial Infarction, Arrhythmias – Greater cardiac workload? – Inadequate myocardial protection of fatty or hypertrophied hearts? – O2 supply/demand mismatch? Pneumonia – Decreased mechanical ventilatory functions – Longer mechanical ventilation times More Pathophysiology Wound Infections – Poor wound healing – Diabetes – Excessive adipose tissue with low regional oxygen tension – Inadequate serum levels of prophylactic abx – Technical difficulties in maintaining sterility of tissue folds Infectious Implications Infection in the setting of cardiac surgery increases morbidity and mortality In a study by Fowler et al, patients with major infection had significantly higher mortality (17.3% vs 3.0%, p<0.0001) and postoperative length of stay >14 days (47.0% vs 5.9%, p<0.0001) Most common risk factors for infection included BMI of 30 to 40 kg/m2, DM, previous MI, and HTN Fat and Fib/Flutter Obesity is a risk factor for atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter in the cardiac surgery setting Postoperative atrial dysrhythmias may be complicated by significant symptoms, hemodynamic instability, and an increased risk of stroke Postop fib/flutter is also associated with increased length of stay and incurs additional costs Lose the Weight and Do Great? In patients encouraged to undergo preoperative weight reduction, there was a trend of better postoperative recovery They had a shorter time in the ICU (1.5 vs 2.1 days), a lower incidence of MI (4.7% vs 6.7%) and arrhythmias (25.7% vs 30.4%), and fewer respiratory infections (3.8% vs 4.2%) Preoperative weight reduction and subsequent postoperative weight control should reduce perioperative complications and improve patients’ long term results References Rana, JS, et al. Obesity and Clinical Restenosis after Coronary Stent Placement. Am Heart Journal. 2005; 150: 821-826. Fowler, VG, et al. Clinical Predictors of Major Infections After Cardiac Surgery. Circulation. 112 [I] 358-365. Martinez, EA, et al. ACCP Guidelines for Prevention and Management of Postop A-fib After Cardiac Surgery. Chest. 2005; 128: 4855. References Cont’d Fasol, R. et al. The Influence of Obesity on Perioperative Morbidity. Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgeon. 1992. 40: 126-129. Birkmeyer, NJ, et al. Obesity and Risk of Adverse Outcomes Associated with CAB Surgery. Circulation. 1998; 97: 1689-1694. Gurm, HS, et al. The Impact of BMI on Shortand Long-Term Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Coronary Revascularization. JACC. 2002; 39: 834-840. References Cont’d Prasad, US, et al. Influence of Obesity on the Early and Long Term Results of Surgery for CAD. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1991. 5: 67-73.