Is it a Mystery??? Case of the Month:

Case of the Month:

Is it a Mystery???

32 y/o post-doctoral student at UT, who moved from India 3 years ago for academic reasons.

The patient presents with one month of febrile illness (not quantified), general malaise, weakness, non-productive cough, weight loss (10 lbs estimation). Few days prior to admission her symptoms have been worsening, as well as new SOB.

The SOB is at rest, but it worsens on exertion. Denies orthopnea, PND or LE edema.

Because of her symptoms, she went to

Student Health, where a CXR was obtained, a PPD was placed and PO antibiotics were administered.

The CXR preliminary report was read as cardiomegaly and “suspicious” appearing right apex.

The PPD was (+).

The patient was referred from Student

Health to the Med ED for further evaluation.

PMHx: malaria when she was 10 yoa

Otherwise negative

Soc Hx: Denies smoking, ETOH or recreational drugs

Meds: Ciprofloxacin 200mg PO BID

FHx: Non-contributory

ROS:

Denies CP. Denies SOB prior to current illness. Good exercise tolerance.

Denies frequent cough, in the past. Denies hemoptysis. Denies unexplained febrile illness or weight loss in the past. Denies night sweats.

Denies arthralgias or myalgias.

Has been a healthy adult until now.

PEX:

BP: 115/70 HR: 105 T: 101 F RR: 21 SO2:

100%

Patient is in mild distress because of respiratory difficulty. AAOX3 able to provide history.

(+) 7 cm JVD, no carotid bruits heard.

Heart: RR no S3, S4 no murmurs or rubs.

Lungs: Bibasilar crackles, otherwise clear.

Abd: soft, non tender, BS +, no guarding.

NO LE edema.

CXR: Cardiomegaly. Bilateral pleural effusions. NO pulmonary nodules.

CT scan chest: Large pericardial effusion.

Moderate bilateral pleural effusions.

Bilateral atelectasis.

The cardiology fellow on call, “Dr. Z” was called.

He noted on his physical exam a pulsus paradoxus of 20 mmHg.

He performed STAT EKG and echo.

Echocardiogram

Na: 141

CO2: 29

K: 3.5

BUN: 13

T Prot: 6.0

Alb: 2.6

SGOT: 26 SGPT: 63

GGT: 141

PT: 14.7

PTT: 34.9

Cl:106

Crea: 0.7

Bili: 0.7

AlP: 175

INR: 1.16

WBC: 14.9 (18)K Hgb: 11 Hct: 33

Plt: 614 K

M: 9%

N: 77% L: 14%

E: 1% MCV: 80.9

MCH: 27

Fe: 24

RDW: 15.1

TIBC: 308

Ferritin: 115

CRP: 8.1

ESR: 98

Anti RNP: 36

ANA: (-) Smith AB: 29

Hep A, B, C (-)

TSH: 1.560

RF: 11.4

Pericardial Fluid

Glucose: 41

pH: 7.5

WBC:10.5 K

N: 46%

LDH: 2432

Protein: 6.8

RBC: 5.4 K

L: 14% M: 10%

AFB smear: (-) Fungal cx: (-)

Aerobic cx: (-) AFB cx: Pending

Adenosine Deaminase: 44.4

PCR for M.tuberculosis

: (-)

Pericardial Biopsy: Reactive mesothelial cells, underlying adipose tissue and paucicellular fibro connective tissue with foci of chronic inflammation consistent with chronic pericarditis. Granulomatous inflammation is not identified.

Special stains are Pending.

Microbiology:

AFB smear (sputum): (-) X 3

AFB cxs (sputum): Pending

Blood cxs: (-) X3

SO??

Tuberculous Pericarditis

Tuberculous pericarditis occurs in 1 to 2 % of patients with pulmonary tuberculosis

Diagnosis of tuberculous etiology in pericardial effusions is important since the prognosis is excellent with specific treatment.

Clinical features may not be distinctive and the diagnosis could be missed. With the spread of

HIV infection the incidence has increased.

Usually presents as a slowly progressive febrile illness. When it presents as an acute pericarditis, which is uncommon, or as cardiac tamponade, which is frequent, the diagnosis is more likely to be delayed or missed.

The delay from hospital admission to diagnosis was 5.2 weeks; diagnosis was first made only at necropsy in 17% of patients.

1,2

1.Sagrista-Sauleda J. Am Coll Cardiol 1988;2:724 –8

2. Rooney JJ. Ann Intern Med 1970;72:73 –8

Chronic idiopathic effusions in which no etiology could be established are a common cause of tamponade varying from

11% –32%.

Without specific treatment the average survival was 3.7 months in a report from

Africa and only 4/20 (20%) were alive at six months.

Pathogenesis

In a rare case there may be direct spread from tuberculous pneumonia, it can be seeded in miliary tuberculosis and in such instances other organ systems dominate the presentation.

Most often the spread is from the breakdown of infection in mediastinal nodes directly into the pericardium and particularly those at the tracheobronchial bifurcation.

Lymphatic drainage of the pericardium is mainly to the anterior mediastinal, tracheobronchial, lateropericardial, and posterior mediastinal lymph nodes and not into the hilar nodes.

Does not show up on routine chest radiographs but can be seen only on chest computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies.

Sir William Osler concluded that caseous mediastinal lymph nodes were the usual focus of pericardial involvement.

1

Rooney et al found that 50% of patients with TPE who were necropsied had pleural effusion due to tuberculous pleuritis.

2

1.Spodick DH. Arch Intern Med 1956;98:737 –49

2. Rooney JJ. Ann Intern Med 1970;72:73 –8

Some authors separate tuberculous pericarditis into four stages:

The dry stage

The effusive stage

The absorptive phase

The constrictive phase

Ortbals DW. Arch Intern Med 1979 Feb;139(2):231-4

Diagnosis

Characteristics of the pericardial fluid :

The effusion in tuberculous pericarditis is straw-colored .

It is uniformly an exudate. The protein concentration is invariably above 3.0 g/dL, and is greater than 5.0 g/dL in 50 to 77%.

LDH level is elevated in approximately

75%, commonly exceeding 500 IU/L.

Glucose concentration is usually between 60 and 100 mg/dL. pH is virtually always less than 7.40.

The nucleated cell count is usually between 1000 and

6000/mm3. It is lymphocyte-predominant in 60 to 90% of cases. Lymphocytes predominate in subacute and chronic tuberculous effusions, while neutrophils predominate in acute effusions.

The fluid rarely contains more than 5% mesothelial cells.

The presence of more than 10% eosinophils usually excludes the diagnosis of tuberculous pericarditis

Only 40 to 60 % of patients with tuberculous pericarditis who undergo pericardiocentesis have acid fast bacilli

(which are virtually diagnostic) on smear.

Strang JI. Lancet 1988 Oct 1;2(8614):759-64

Fowler NO. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 1973; 16:323

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

PCR technology has been used for nucleic acid amplification. Overall accuracy of

PCR approached the results of conventional methods. The sensitivity for pericardial fluid was poor and false positive results with PCR remain a concern.

Sensitivity in pleural fluid is 42-81%.

Cegielskyi JP. J Clin Microbiol 1997;35:3254 –7

Lee JH. Am J Med 2002;113:519 –21

Serodiagnosis

ELISA: A sensitivity of 61% (at 96% specificity) was achieved. It is unlikely that this technology will be widely applied.

NG TT. Q J Med 1995;88:317 –20

Adenosine deaminase

Adenosine deaminase levels are believed to reflect T-cell activity. The levels with TPE have varied from 10 –303 U/l, and with a cut off level of 30 U/l the sensitivity was 94% and specificity

68% with a positive predictive accuracy of 80%.

1

High ADA levels that may occur in other conditions, like rheumatoid, empyema, mesothelioma, lung cancer, parapneumonic, and hematologic malignancies.

1. Burgess LJ. Chest 2002;122:900 –5

2. Komsuogluo B. Eur Heart J 1995;16:1126 –30

Interferon-gamma

Median concentration in TPE was >1000 pg/l and significantly higher than malignancy or non-tuberculous effusions

(p<0.0005). A cut off value of 200 pg/l for interferon-gamma resulted in a sensitivity and specificity of 100% for the diagnosis of

TPE.

Burgess LJ. Chest 2002;122:900 –5

Histological evidence

Histological evidence of a tuberculous granuloma with the demonstration of acid fast bacilli would be a definite diagnostic criterion.

The typical granuloma is however not always found and the pericardial biopsy may show nonspecific findings even when M tuberculosis is found in the pericardial fluid. Strang et al reported 29% of non-specific findings on patients whom M tuberculosis was recovered from the pericardial fluid.

Strang JIG. Lancet 1988;ii:759 –64.

Myocardium with epicardium and part of the pericardium. In the epi- and pericardium a granuloma is present (right half of image), with caseous necrosis, lymphocytes, and epitheloid cells. The myocardium (left quarter of image) is not involved in the inflammatory process.

Chest computed tomography

Enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes >10 mm detected on chest computed tomography have been reported recently in virtually 100% of patients with TPE.

They were found in all 22 patients with

TPE and none of a control group with large viral/idiopathic or postoperative pericardial effusion.

Cherian G. Am J Med 2003;114:319 –22

Features of Mediastinal Nodes in TPE:

Aortopulmonary, paratracheal, and carinal nodes most often involved.

Typically coalesced (matted) with hypodense center.

Hilar nodes rare and inconspicuous.

Nodes seen only on chest computed tomography or MRI.

Nodes disappear or regress on specific treatment.

Echocardiography

The pericardial exudate is thick and fibrinous with a tendency to form adhesions and in some instances constriction. On echocardiography there are patchy deposits with "fibrinous" strands criss crossing the pericardial space.

LIU PY. Am J Cardiol 2001;87:1133 –5

Large pericardial effusion and inversion of the right atrium, caused by elevated pericardial pressure, in late diastole and early systole.

A parasternal short-axis view shows that the right ventricular outflow tract is compressed in diastole because of the elevated pericardial pressure.

Nardell E. N Engl J Med 2004; 351:1804-1805

Culture of mycobacterium tuberculosis

Recovery from the pericardial fluid has varied from 30% –100%. Strang using special techniques was able to culture M tuberculosis from all patients. The specimens were cultured in double strength Kirchner culture medium after bedside inoculation and also conventional culture in Stonebrink medium.

Strang JIG. J Infect 1994;28:251 –4

.

Role of corticosteroids

In active constrictive pericarditis, the addition of corticosteroids to standard antituberculous chemotherapy reduced mortality and the need for subsequent pericardiocentesis.

A similar effect is observed on pericarditis with effusion, when coupled by initial pericardial drainage.

Prednisone 60 mg/day for four weeks, 30 mg/day for four weeks, 15 mg/day for two weeks, then 5 mg/day for week eleven.

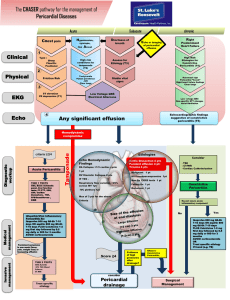

SUGGESTED APPROACH

Ascertain if there is a prior history of tuberculosis, tuberculosis exposure, of prior PPD skin test reactivity, or if the patient is immunocompromised.

Perform an intermediate strength PPD skin test on all patients

If the PPD skin test is positive or the patient is immunocompromised and an alternate cause (eg, lupus, malignancy, trauma) is not present, empiric antituberculous and prednisone therapy can be initiated.

If, however, there is hemodynamic impairment, subxiphoid pericardial biopsy and sampling of pericardial fluid should be performed.

If the biopsy shows granulomatous changes and/or AFB, smear of the pericardial fluid is positive for AFB, or the probability of tuberculosis is highly likely.