A report on the Scientific Symposium “Leer het brein kennen”

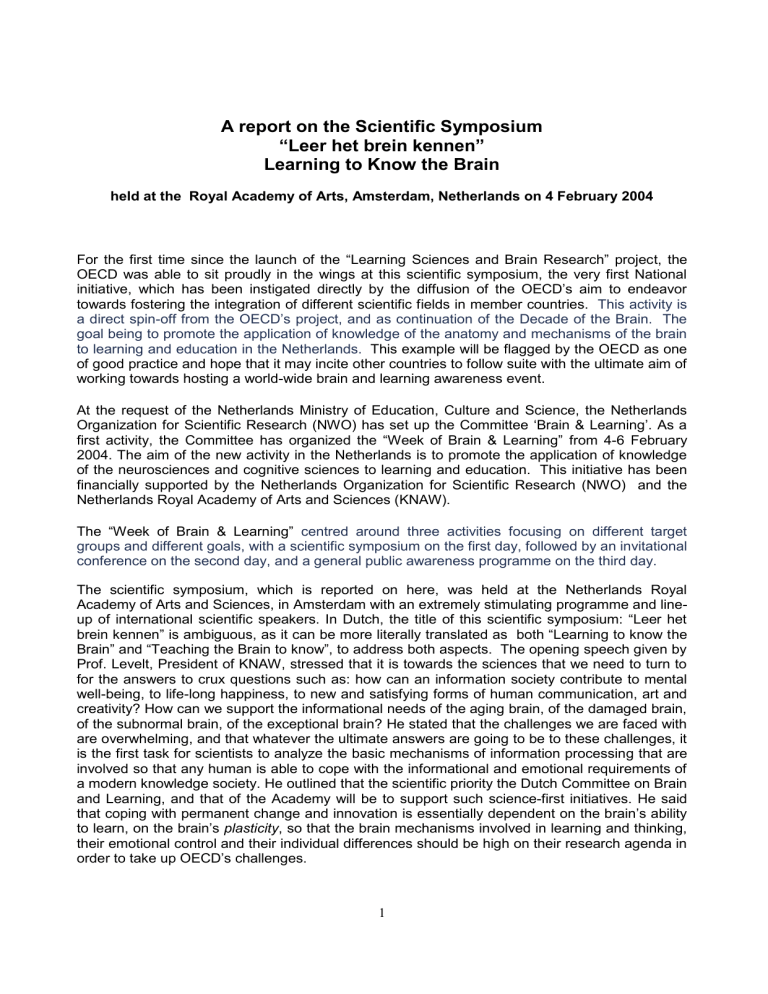

A report on the Scientific Symposium

“Leer het brein kennen”

Learning to Know the Brain

held at the Royal Academy of Arts, Amsterdam, Netherlands on 4 February 2004

For the first time since the launch of the “Learning Sciences and Brain Research” project, the

OECD was able to sit proudly in the wings at this scientific symposium, the very first National initiative, which has been instigated directly by the diffusion of the OECD’s aim to endeavor towards fostering the integration of different scientific fields in member countries. This activity is a direct spinoff from the OECD’s project, and as continuation of the Decade of the Brain. The goal being to promote the application of knowledge of the anatomy and mechanisms of the brain to learning and education in the Netherlands. This example will be flagged by the OECD as one of good practice and hope that it may incite other countries to follow suite with the ultimate aim of working towards hosting a world-wide brain and learning awareness event.

At the request of the Netherlands Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, the Netherlands

Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) has set up the Committee ‘Brain & Learning’. As a first activity, the Committee has organized the “Week of Brain & Learning” from 4-6 February

2004. The aim of the new activity in the Netherlands is to promote the application of knowledge of the neurosciences and cognitive sciences to learning and education. This initiative has been financially supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) and the

Netherlands Royal Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW).

The “Week of Brain & Learning” centred around three activities focusing on different target groups and different goals, with a scientific symposium on the first day, followed by an invitational conference on the second day, and a general public awareness programme on the third day.

The scientific symposium, which is reported on here, was held at the Netherlands Royal

Academy of Arts and Sciences, in Amsterdam with an extremely stimulating programme and lineup of international scientific speakers. In Dutch, the title of this scientific symposium: “Leer het brein kennen” is ambiguous, as it can be more literally translated as both “Learning to know the

Brain” and “Teaching the Brain to know”, to address both aspects. The opening speech given by

Prof. Levelt, President of KNAW, stressed that it is towards the sciences that we need to turn to for the answers to crux questions such as: how can an information society contribute to mental well-being, to life-long happiness, to new and satisfying forms of human communication, art and creativity? How can we support the informational needs of the aging brain, of the damaged brain, of the subnormal brain, of the exceptional brain? He stated that the challenges we are faced with are overwhelming, and that whatever the ultimate answers are going to be to these challenges, it is the first task for scientists to analyze the basic mechanisms of information processing that are involved so that any human is able to cope with the informational and emotional requirements of a modern knowledge society. He outlined that the scientific priority the Dutch Committee on Brain and Learning, and that of the Academy will be to support such science-first initiatives. He said that coping with permanent change and innovation is essentially dependent on the brain’s ability to learn, on the brain’s plasticity , so that the brain mechanisms involved in learning and thinking, their emotional control and their individual differences should be high on their research agenda in order to take up OECD’s challenges.

1

Notes jotted from the presentations:

The first speaker, Prof. Uylings from the Netherlands Institute for Brain research and VU

University Medical Center, already well-known to the OECD Lifelong Learning Network, gave a morphological, developmental profile of the human brain, including the topic of different kinds of

‘critical periods’. Although the morphological development reaches full-grown sizes around 4-5 year, the neurochemical/ transmitter development takes place till the end of puberty/ begin of adulthood. With its network of 27.4 billion neurons making up the human cerebral cortex, each human and its brain are unique. There is a large inter-individual variation not only in size but also in brain structure and function.

This theme was elaborated on by the following speaker Prof. Boomsma, of the Vrije University in

Amsterdam, whose talk was focused on how genes together with the environment contribute to variations in the brain. Her interesting longitudinal research study on IQ data in twins highlights their independence as being due the role of environmental exposure as opposed to genetic. Of extreme interest to the OECD was the revelation from her findings that when parental education is higher, the influence of genetic variations on verbal IQ is larger, whereas, in lower SES subjects the genetic difference between sibling influences comes from the environment. This could potentially hold the key to some explanations of poor school results, as if you interpret this in the context of the school as the environment then: if it is bad, then the gap between low SES students compared with students with higher parental education is even further enhanced. In addition, the outcome of the national school-tests around the age of 11-12 year is largely determined by the genetic background of the students.

The third speaker, Prof. Leseman from Utrecht University’s talk tied into this, as he highlighted the importance of interaction with the environment in relation to the role cultural and individual differences play in young children. He touched on the role of motivation, the importance of scaffolding which needs to be adapted to different levels, and suggests that we need to strive towards a neuro-constructivist approach to learning. However, before this can take place, additional steps in theory, simulation modelling and developmental and educational research are needed.

Prof. Keith Stenning, from Edinburgh University, then took the floor on the contentious debate on the acquisition of general reasoning skills as being vital and lacking from curriculums. He stated that we live in a knowledge economy but have dropped the tool we need most to learn in that world, i.e. logical education. He left us with the reflection on whether a more abstract transfer of this logical teaching should be sought.

The next presentation was on the neuroscientific basis of chess playing and applications to the development of talent and education by Prof. Atherton of the Brain, Neurosciences and

Education American Educational Research Association, in the USA. Findings from various studies on the neuroscience of chess playing have shown that although the frontal lobe is initiated in high levels of chess competence, there are other cortical areas whose involvement may be enhanced by training and interventions. So, this suggests that attempts to locate general intelligence in one area of the brain, is unfounded. What is imperative for educators to retain is the neurological analysis of the development of expertise, and the impact of selected interventions.

The following two presentations focused on the brain’s plasticity, the first given by Prof. Hagoort of the University of Nijmegen who stipulated the vital need to optimize our learning environments

2

in order to understand how brain plasticity can be recruited in a learning situation. He warned that in order to reach for brain-based learning science, we need to fight against pseudoscientific nonsense. Prof. Hagoort was excited by a recent finding published in the January 2004 edition of

Nature where in people who had learnt to juggle, certain brain areas had grown. But three months later, during which time these people stopped juggling, the brain had gone back to its normal size.

Dr. Bruce McCandliss of the Sackler Institute, who is the main Scientific Advisor of the OECD

Literacy Network, then gave a talk on plasticity and learning to read. He stressed the need to develop cognitive interventions to make up for core-cognitive deficits and that it is what you attend to that has a profound impact on learning change.

The floor was then given to one of the educationalists on the programme, Dr Schirp from

Germany, to reflect on the big question on how to bring research findings to practitioners, and come up with brain-friendly teaching and learning. He stressed the need to improve the quality of teaching and the sustainability of learning. He stated that the common metaphor that compares the brain with a computer is false, as our brains cannot be simply fed with data, which is stored and then retrieved. Our brains need to process and assimilate information, so we need to find ways to stimulate our brains wh ich are specialized to tune in knowledge with experience. Shirp’s remedy for change is for children to be given more emotive and cognitive challenges, to bring in experts outside of the school and introduce more self-organised learning.

The final session of the day composed of three speakers on the topics of lifelong learning and aging. Firstly, Prof. de Lange of Utrecht University, Freudenthal Institute in the Netherlands gave a talk, which critiqued the relation on what is currently taught in schools as opposed to what is needed for knowledge and skills for life. He said we need to look at how: knowledge about learning relates to school learning: knowledge about the brain can be incorporated into school learning, to achieve literacy/numeracy after school, and how to teach researchers themselves literate skills to communicate their findings.

Prof. Jolles of the Institute for Brain & Behaviour of the University of Maastricht, who was the chairman of the Netherlands committee in putting together this symposium, and who is also a core member of the OECD Lifelong Learning Network, talked on learning and successful cognitive aging. He drew on results from the Maastricht aging study which shows that age affects various aspects of learning differently, and that frighteningly already in the 4 th decade of our lives that many declines in cognitive function have already begun. So, the question is: how to address the reality of the fact that there are many teachers out there around the 45-year age mark confronted with younger brains, who are required to undertake information processing tasks, when their brains already compromised? However, he says we should rest assured, as the brain is dynamic and there is plasticity, so that changes/strategies are possible to make up for decline and to sustain a successful long life. The final presentation given by Prof. Bäckman of

Sweden gave further hope for such a change and memory improvement in adulthood and aging.

He reassured us that even severely impaired individuals under supportive conditions can show improvement.

The conclusions to the symposium where drawn by Bruno della-Chiesa, head of the OECD project .

3