>> Amy Draves: Thanks so much for coming. ... welcome Michael Cusumano to the Microsoft Research Visiting Speaker Series. ...

advertisement

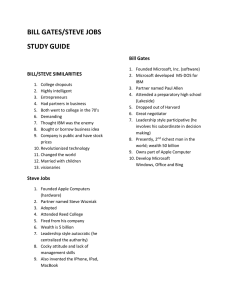

>> Amy Draves: Thanks so much for coming. My name is Amy Draves, and I'm pleased to welcome Michael Cusumano to the Microsoft Research Visiting Speaker Series. He's here today to discuss his book, Strategy Rules: Five Timeless Lessons from Bill Gates, Andy Grove, and Steve Jobs, in which he examines their successes, failures and the practices and strategies they pioneered while building their firms. Michael Cusumano is the Sloan Management Review Distinguished Professor of Management at MIT's Sloan School of Management. He specializes in strategy, product development and entrepreneurship in the computer software industry, as well as others. He has published 13 books, including Staying Power, and many articles in publications like the New York Times and the Economist. Please join me in giving him a very warm welcome. >> Michael Cusumano: Thank you. Do you want me to stand behind the mic, or is this fine? No, this is amplified. Okay, so it's great to be back at Microsoft. I was here yesterday too, by the way. So again, I would like to talk about this book, and I hope you permit me to waltz a little bit down memory lane. So here is a photo not many of you have ever seen, but this has sat in my office for more than 20 years. This was taken back in 1992 I think, '92 or '93, and Bill doesn't look too happy, but we were grilling him on software development methods and strategy and all sorts of things. You look surprised. >>: Who are the other people? >> Michael Cusumano: Who are the other people? Okay, well, this person is me, right? Do I look at all similar? >>: You've got the same shirt on. >> Michael Cusumano: It's the same type of shirt. But I do still have that shirt in my closet, though. Yes. So this is so old that it faded, actually. You don't see the color. That shirt was kind of brownish. So to my right is Rick Selby, who was my coauthor for this book we did on Microsoft, came out in 1995, Microsoft Secrets, which was really the first in-depth look at how Microsoft worked, particularly the development methods. And at that time, almost all computer science departments or software engineering departments were teaching traditional waterfallish kinds of methods, and I was studying the history of software engineering. I'd written a book on software factories. Then I wanted to see, what do PC makers do, and what does Microsoft do? So one of my students who worked for IBM got me an entry into Microsoft, and I came and met the fellow to the left of Bill Gates, who is David Moore. Dave Moore at that time was the Director of Development at Microsoft. He then left, worked with Paul Allen for a while, and then came back, so he's back at Microsoft now for quite a few years. Anyway, I was very impressed with what Microsoft was doing. I figured you guys had a way of kind of organizing chaos, and we called it the synchronize and stabilize method, kind of an early version of Agile in a sense, and that was the book Microsoft Secrets, which is up there on the left. It sold about 150,000 copies, 14 languages. A guy named Mike Maples was our executive sponsor at the time. Anyone heard of Mike Maples before. Okay, you guys. So Mike, Bill had hired him from IBM, and he came in and started introducing some real process and structure to Microsoft. Things were getting very chaotic, and it was getting very difficult to ship anything complicated. This was the late 1980s, and Mike Maples came in, and Microsoft Secrets was part of an attempt -- part of his attempt -- to get some better understanding of what were the better processes being used within Microsoft that actually worked. And actually, the most sophisticated group at that time was the Excel group, which was run by a guy named Chris Peters, who went on to Boeing fame, and so we got access to Excel, Word group, and then also the Windows NT group, which at that time was also trying -- your first group of really professionally trained software engineers and architects. Anyway, that was the Microsoft Secrets story, and then three years later, David Yoffe, who was a professor at Harvard Business School and a good colleague of mine from my graduate school days -- he's also the longest-serving member on the Intel Board of Directors, joined Intel Board around 1988 or so, after writing a case on Intel. He and I teamed up and wrote a book, competing on Internet time, about the challenge from Netscape to Microsoft, and I did another book, 2002, Platform Leadership, which was trying to pull together all of the ideas that I had been seeing for many years about the difference between a pure product company versus a platform company, which Microsoft really was. Business of Software, 2004, then Staying Power, 2010, and then the Strategy Rules book. So this particular photo, as I mentioned, was at this anniversary party, Time Magazine. Andy Grove had just before this been named Man of the Year, and Bill Gates had been named Man of the Year a bit before that. Interestingly enough, Steve Jobs was never named Man of the Year for Time Magazine, but anyway, this is a unique photo. Three guys that were very close to each other and in many ways created let's say the intellectual foundations of the modern high-technology world that we live in and that you guys all work in or struggle with. And so David Yoffe and I had some interesting I guess ties with each of these three guys and their companies, and just after Steve Jobs died -- I guess it was October 2011, David called me up and said, it's time that we write a book about these three guys, and you and I are the people to do it. Let's do it. So I said, well, I'm kind of looking forward rather than backward, but I agreed it was a good thing to do, and it was a lot of fun. So we spent about a year talking about what we would write, and then we wrote it, and it came out in April. But I would say in the first or second meeting, we had the whole structure of the book already laid out. It was pretty much immediately apparent to David and I what the book should be about, and it was really about the common elements in their thoughts. I'll talk a bit about that. Give you a flavor of what the book was. So here's the context of the study. These are three very, very different people, tremendous influence on each other, particularly Andy Grove and Steve Jobs became very close friends. And Steve Jobs and Bill Gates were actually early partners. You wouldn't have an applications business without the partnership that they developed in 1983 or so around the Macintosh. And tremendous rivals, as well as colleagues. They've never been compared before, the three of them together, so this was kind of a unique opportunity for David Yoffe and I, and again, very different. Gates' background you all know. Jobs', as you also know, orphan flower child, both college dropouts. Andy Grove, you might not know the background so much. He's 20 years older than these two. Gates and Jobs are the same age. They're both a year younger than me, for what it's worth. But Andy was 20 years older, born in Hungary, escaped from Nazi Hungary during World War II, made his way to New York City, did a free college degree in chemistry at City College of New York then, did a PhD at Berkeley in chemical engineering. And the differences in these three guys, we argue in this book, really explain many of the differences in the three companies that you see today, so I'm going to get into what I mean by that. Three extraordinary records, don't have to really go into this in much detail, but it's interesting that at their peak, each of these companies was the most valuable company in the world, about $1.5 trillion of value. I was at a talk yesterday that Harry Schum was referring to the valuation of Microsoft in '99, $6 billion to $12 billion. In today's dollars, that would be $800 billion, so more valuable than even Apple. So they've really had a tremendous ride at their peak, and again, all these companies ultimately presided over what we now call platform businesses that have this linear -- exponential growth potential, not a linear growth potential, like conventional companies. So they were, as we argue in the book, they were in the right place at the right time with the right kind of technologies to generate this wealth, but there were a lot of people who tried to do this, as well, and failed. So what did these three guys do? So here's kind of how we end up coming out at some level, and there's a lot of things in the book, and I'll give you a quick overview. But we introduced this concept of a personal anchor and really an organizational anchor, and that each of them started a company or was there on day one of a company and had a particular lens on both what the future would be and what they could do with their organization. So Gates, as I'm sure everybody here knows his history, at least as well as I do, programming in middle school and high school, a software company in high school, access to a computer. Of course, he was lucky to have that, but an insight when he created Microsoft that you don't actually have to write software for each application. You can write it once and then sell it a thousand, million times, so that was really his deep insight in 1975. I'm going to go back to the motivation a bit more, and essentially, that's the software product model. Really, the first at least mass-market software company. Jobs basically at the same time, a year later, this insight in 1976 that he wants to bring complex new technology to the average person, and that sense of design really distinguished Steve Jobs. And again, it's very important that he was not a geek programmer like Bill Gates, and again, so his whole thing was how do you make this technology accessible to someone like me. And if you think about it, these two perspectives have defined these two companies, even today. Apple is still focused on making complex technology simple, easy, elegant, easy to use for the average person. Microsoft is still much more driven by the technology, and again, sells technology to other technologists. That's where Gates started, right? Programming tools. And Intel was a different story, and in some ways, Intel made all this possible, because it was their ability to create a microprocessor that provided the opportunity for Gates and Paul Allen to create a programming language, Basic, for the first PC kit. It would not have happened without Intel. Apple would not have happened without Intel, either. But Grove was different, not a programmer, but a PhD in engineering, and he had worked at Fairchild Semiconductor before Intel. Intel was founded in 1968. And Fairchild spawned all these great entrepreneurs and all this great technology, but it was a chaotic engineering organization. They weren't able to really mass produce anything and had trouble manufacturing, and he was determined that would not happen in Intel, and that, we call it the pursuit of discipline. Making the art of semiconductor manufacturing into an engineering science was what he tried to do at Intel. And you put these three together, you have not only personal anchors but organizational anchors as they hired people and built a culture around them, right? Okay. And of course, even after they stepped down as CEO, these companies have continued to do well, not quite as well as they did in their peaks in terms of valuation, but still have done remarkably well. So they've created platforms or franchises that really have endured but had some trouble adapting to change, whereas Apple had less trouble adapting to change, and we kind of make the argument there -maybe it's obvious, but building these kind of devices really required a simple user interface, and that was what Steve Jobs was about, from 1976, and it mattered less in the era of personal computers, but when it came to these devices, it really mattered, that insight he had and that design sensibility. And we think other things came into play. The fact that Apple essentially lost the battle for the personal computer gave Jobs the freedom to try something different, to try something new, and as a matter of fact, he abandoned the PC or changed or broke with compatibility in the Macintosh platform three times, and then created a whole new platform, something that Microsoft never really did, and it turned out that newer, optimized platform for handheld devices was much more important in the era of these devices. And of course, Intel didn't do it either, pretty much stayed on the PC. So that early personal orientation was very important in defining what happened to these companies. Okay, so we talk about these personalities and how they were infused into the company, this notion of a personal anchor moving on to becoming really an organizational anchor. Each firm also not only came to embody the personalities of these three guys but their strengths, as well as their flaws, and we write about this, as well. Gates, Grove and Jobs were at least as -- I'm going to talk about as individuals, but as leaders, they were deeply flawed, and not until they recognized those flaws and really found a way to compensate for them were they really successful. And Gates I will say kind of recognized it first, and he recognized a lot of things first, and he continued to be flawed, but he really built a very good management team. And I've already described why we think Apple was able to thrive in the newer era, whereas Microsoft and Intel had trouble. I'm going to get back to that. So this is the story we tell. Okay. And you don't have the actual physical books there, but I'm told you will get them eventually if you sign up for it. >>: Are they available on the Web? >> Michael Cusumano: Are they available on the Web? Is there a free version on the Web? >>: From Amazon. >> Michael Cusumano: Oh, absolutely. You can buy it from Amazon, Barnes and Noble, of course. And there's Kindle versions, as well. Kindle might be a bad word here, but it's available. Of course. Okay. So here is the list, and in some ways, I feel like I'm in the business of making lists. I do a lot of it as a professor, but I like to organize books around sets of principles that are easy for managers to understand. Microsoft Secrets is organized around five principles or so. So is Staying Power. So is Competing on Internet Time. So here, we came up with a set of rules or high-level principles that we defined how at least eventually Gates, Grove and Jobs came to see the world and to run their companies. And we think these kind of represent a common approach, and that's surprising, because they were so different, and the companies they created were so different. And again, this is not a random sample of high-tech CEOs, so this is not -- there's clearly some bias here. However, I will say David Yoffe and I have been observing these three companies for some 30 years, so it's not as if we were just looking at the end of some process at three successful guys. We were kind of there along the way, and it wasn't always obvious that they would be successful. Most of the time, Apple was not successful, so it's interesting how all this comes together at this point. So the first principle that we talked about in the book is this idea of look forward, reason back, that they were able to get a sense of what the future might be, but not only did they do that, they identified some very concrete actions as to what they would do. I'm going to go into this a little bit more detail today, and that may be the only principle I talk about in any detail because of time. So some people will say that these guys foresaw the future. We don't really see it that way. We see it as they created this future that we all have experienced, and they had some ideas or some data in front of them that helped them see that future, and we talked about extrapolation and interpreting that data, so I'm going to get back to that. The second one we called make big bets, without betting the company. Be bold and ambitious to really change the game, change the industry at the time. You maybe don't realize it today, how revolutionary Microsoft and Apple actually were. But we were quite impressed with how careful each of them was, even Steve Jobs, who was in many ways the most reckless of the three, but how they were careful in what they did. They never really put bankruptcy of the company at risk, and they took some very bold moves, so I can get into a few of those examples. Build platforms and ecosystems, not just products, because of the interdependence of technology. And again, I've been writing about this since -- in many ways, since 1987, when I first wrote a paper on VHS and Betamax and then was surprised at why the better product went from 100% market share to 0% in a few years. Why was that? It wasn't because of the product. It was because of some other dynamics, platform dynamics, and we didn't have the word platform then. We didn't even really have the word network effects then, but we had network externalities and bandwagon dynamics. These guys eventually came to understand it and leverage it and make it the center of their strategy, not at the same time, and that's another interesting story. Exploit leverage and power, master both of what we called judo strategy as well as sumo strategy. I don't have time to really go into this, and I think you understand all the power plays that companies like Microsoft and Apple and Intel have done, but particularly in the early years, they were also very quick and flexible and clever. And even when Apple moved into new businesses, like iTunes, very quick and flexible, and negotiating from a position of what seemed like weakness. And then the final point, which I've also given you some inclination of, shape the company around your personal anchor. And here's a tough one. If you don't have anything valuable, then you probably shouldn't become an entrepreneur, but if you have some really strong ideas that other people can share and that seem to be linked to what is happening in the world, then I think you've got a basis for creating a company or a division of a company. And these guys all did that. They created a company around these ideas, and again, they figured out how to compensate for where they had major gapes in their interest or knowledge. So this is the list that David and I came up with pretty much on day one of talking about this book, but I think what's really interesting are the details. Okay. So here, let me just give you an example of what we've done. Strategy rule one, look forward, reason back. This is about how do you develop a vision of the future? You look back. You have some sense of where you think the future will go. You kind of set boundaries and priorities for yourself, what are you going to do? What are you not going to do? You've got to anticipate customers and competitors and also how the industry might change, inflection points, which Andy Grove used. And, of course, commit to change but kind of look frequently enough so that you can understand changes and make periodic course corrections. So in general, we think these three guys did this, but they did something much more, and again, we are professors looking at a history we know well, so I don't think in real time they had this framework in their heads. But if we look at what they did, this kind of describes it. So first, that vision comes from extrapolation, from something that they know to be true, and interpretation as to what this information means. Okay, and particularly for them, and that's where the point of view comes in. What does this view of the future mean for what they as entrepreneurs might do today and also looking out. And out of this kind of extrapolation, interpretation viewpoint came vision statements that were very simple, clear and actionable. But then the harder part came of what we call reasoning back, so it's figuring out, okay, not just some idea of what the future is likely to be, but what can they do today? So deciding to create a version of Basic for this new microprocessor that's come out for an industry that didn't yet exist is an example of looking forward and reasoning back. And each of them were very good at taking an idea and creating essentially a product from it very, very quickly. And it's kind of counterintuitive. We thought about this, because most of us want to learn from history, so we tend to kind of look back and reason forward, and this is a natural process, and these three guys did this, as well. Bill Gates was very familiar with IBM's history in the mainframe. He knew a clone industry had appeared, and he kind of figured out that when IBM came out with a PC that a clone industry might also appear, and he kept the rights to DOS, for example. Grove, very much the obsession that Intel developed with process and manufacturing came from his experience with Fairchild, as I mentioned before. And Jobs, again, not an engineer, and that of course greatly shaped how he thought, but growing up in Silicon Valley, seeing great engineering companies like Hewlett Packard, really shaped the way he thought. So they were looking back, but they really looked forward for the most part. When they created their companies, they did that. And again, we think this is a trait that we will see in pretty much all very successful strategists and entrepreneurs. And if you can't do it yourself, you need to do it with a team, and they did have teams around them to help them. Okay, all right. So here's where I think this study really got interesting for us, because we knew all these things, but we really hadn't sat down and realized it until we wrote the book. So here's what really drove Gates, Grove and Jobs. It was Moore's Law, and I don't think I have to ask in this audience, do you guys know what Moore's Law is? I don't have to ask you that. I was with a group of bankers a couple weeks ago. I had to ask them. And so Gordon Moore, obviously the founder of Intel, he was Andy Grove's boss, had been asked around 1966 or so to write a paper on the future of the electronics industry, so he looked back at data and said, you know, density of microprocessors is kind of doubling every 18 months to two years, and projecting forward, he thought there would be -- this would create tremendous changes in the industry. By the time Bill Gates was a freshman or a sophomore in college, 1974, '75, this had become common knowledge. Pretty much everyone believed that Moore's Law was kind of ruling the high-tech world and was going to change computers, consumer electronics. I would say pretty much everyone who deeply understood what was happening in circuit technology, and not your average person on the street. But it had even reached Steve Jobs. Okay, so here's Gates' vision, 1975. He or Paul Allen sees the picture of the MIPS personal computer kit in an electronics magazine, brings it to Bill, shows it to him and says to Bill, we need to make some computer components. We need to be part of the personal computer revolution. The company filing in 1975 uses the phrase, a computer on every phrase in every home, the assumption running Microsoft software. Gates, again, with Paul Allen doing this, but again, most computer companies at that time, and even Apple, founded the next year, were making hardware or hardware and software. So here's what happened. So Gates sees Moore's Law, thinks about what that means and says, well, the implication is that computers are going to be everywhere. They're going to need software. I'm going to create a software company. Again, his lens is he understands software. He understands programming. Doesn't really know much about hardware. We asked him later about this, but he had another interview that was done in 1994 where he talked about this, and this was his thought. I thought we should do only software. When you have the microprocessor doubling in power every two years and essentially you can think of computer power as almost free, so you ask, why be in the business of making something that's almost free? What's the scarce resource? What is it that limits being able to get power out of that infinite computing power? Software. Okay? And then we have Microsoft. Steve Jobs, okay, takes Moore's Law, computers are going to be everywhere, but we have to make them as easy to use as a toaster or a typewriter out of a box. He's not Bill Gates. He's not Andy Grove. He's not a technologist. That's his insight, 1976. We kind of know this, but it really goes back to Moore's Law, and it's not just the Macintosh. It starts with the Apple II, which you pulled out of a box and you put on your desk and used almost like it was a toaster or a typewriter, and then the Mac, with the graphical user interface. And now his vision evolved, but it still stayed around making this complex technology as simple to use as any consumer electronics or consumer appliance. You take it out of a box and use it. And a 2001 quote from him, we think the PC is evolving. The future of computing lay in finding a way to allow users to create, share and add value to the explosion of digital devices. The Mac can become the digital hub of our emerging digital lifestyle. So if you guys remember, in the early days, the Mac was still the center of everything, even after iPod and iTunes came out. Andy Grove, something different. Andy Grove, thinking deeply about Moore's Law, Gordon Moore is in the office next to him saying what this means is that computers are going to be everywhere, but that means we're going to move to a world of mass production and specialization, and the vertically integrated guys like IBM and Digital Equipment Corporation, they won't be able to keep up with the speed of technological change and specialization, so what's going to happen is the vertically integrated computer integration is going to disintegrate. And at that time, they were supplying semiconductor memory products to mainframes. So it's going to disintegrate, dominated by PCs. If we're going to have a place in this, we need to specialize too, and he ultimately decided, we'll focus just on microprocessors, and actually, his salespeople pushed him in that direction, but that's what they decided. So most of you I think are familiar with this chart. This really came out of Andy Grove's head, developed really in the late 1980s, but he published it in a book, only the paranoid survive, in 1976, but that's where it came from. And David Yoffe remembers debating this and discussing it in the Intel board meetings. Okay. And actually, this is a later one, where they had a big discussion in Intel about they could build other whole computers and software. And when I did Microsoft Secrets in 1995, Intel had more software engineers than Microsoft did, but they deliberately decided not to compete with their competitors, but to enable them and let everybody grow the pie together, and they'll take their 85% of the microprocessor slice, and they would brand their chips to try to keep some differentiator. The reason there was a compatible chip business was because IBM early on had insisted on a second source to the 8088 and the 8086 chips, so that really enabled the compatible chip industry, AMD, today. And then they decided not to do that anymore. That's one of the big bets that Andy Grove took. Okay, so I would say that even though David Yoffe kind of lived through this and saw these companies, we didn't really put these pieces together until we thought through very specifically what they did. Here's a quote also from Les Vadasz, who was head of technology strategy at Intel for many years, talking about Andy Grove. There are many managers who make that five-year plan, and then around year three, they start to think about the next five-year plan. Not Andy. Grove understood a basic truth. You can only look so far, and so you better just keep looking frequently. That's the important element of strategy. You understand the direction you're going, but you also know what you're going to do in the next six months. Most companies will do a pretty good job many times about the direction, but then they'd never break it down to shorter metrics. Intel did a super job on that. Well, here's my kind of pause for reflection, but what is the next Moore's Law and what is the implication going to be? We've seen a few of these things already, mobile devices, cloud computing, whatever you want to talk about. What are the current facts for extrapolation and interpretation? How far can we see? What other resources might almost free or more scarce? What are the disruptions and new opportunities? These guys went through this kind of thought process, whether they realized it or not, so I've done this exercise with a bunch of companies. I did it yesterday with a group of Chinese senior policymakers, and their view is that in the future, China is going to figure out a way to make energy very cheap, and that's going to change the world. I did it with bankers a couple of months ago, five different groups. Four of the five came back saying the world is going to change because of crypto currencies or digital assets. We won't be able to charge transaction fees anymore at some point in the future. It's going to completely disrupt their business model. Anyway, this kind of thinking, and I think it goes at lower levels to your different businesses, but it's worth doing this kind of exercise. Okay. Just a few quotes, and we've taken quotes from interviews and past work that we've done with Gates, Grove and readings about Jobs. I was actually at a talk that Bill gave in 1993, and he made this comment. Microsoft bet the company on graphical interfaces, but it took much longer than I expected for the interface to move into mainstream. He didn't actually bet the company, because he had DOS and he had applications, but the break with IBM was a very big bet he made. Very important quote from Andy Grove. There's at least one point in the history of any company when you have to change dramatically to rise to the next level of performance. Miss that moment, and you start to decline. His moment was 1990. He almost jettisoned the x86 architecture in favor of RISC architecture. His experts were telling him, RISC is the future. Now, maybe, had he done that, things might have been different for Intel in many ways, but at the time, it would have been devastating, because again, the whole platform concept was around that architecture and the connection of Windows and DOS to it. So at that moment, he decided not to do SISC -- and not to do RISC. To stay with SISC and integrate some of the better technical concepts from RISC into the Intel architecture. Steve Jobs, Dylan, Picasso, always risking failure, this Apple thing for me is that way for me. I don't want to fail, of course. If I try my best and fail, well, I've tried my best. And again, Jobs was the riskiest of the three, made the biggest bets, but he had the least to lose. He never had the kind of annuity revenue stream that Intel and Microsoft had created. Okay, there are some examples here about being bold but not reckless. I don't want to go through all the details. You guys can kind of read the book. Here's another interesting tidbit, and then I'll kind of end in a few minutes and let you go to some questions. I can't really give you the whole flavor, but there's some data on Apple, and people forget that Apple was kind of a fledgling company. Probably the biggest mistake Bill Gates ever made was to bail Apple out in 1997, investing $350 million into the company. Had he not done that, actually, Microsoft today would probably have 60% of the smartphone business or something like that, or maybe more. What happened in 2003? What changed at Apple? I spent a lot of time on this here. Anybody know? Anybody want to guess? >>: [Indiscernible]. >> Michael Cusumano: The iPod and iTunes came out in 2001. It does have something to do with it. >>: iPod on Windows. >> Michael Cusumano: Yes, iPod on Windows. And this was written about in the Jobs biography. I wrote about it in 2010, in my Staying Power book, but to me, this is the time -- this is the year where Apple kind of compromised, where Jobs allowed his management team to overrule him, and he kind of compromised on this complete product control idea, and also compromised on the goal of making the Macintosh the center of the universe. That was really the critical idea, because until this time, you could only use an iPod and iTunes if you had a Mac. So in the fall, big fight in Apple, and the Mac was about 2% of the global PC market share at that time. Windows was most of the rest, and the team finally overruled him, and he allowed that to happen, and then he committed. He said, well, ultimately, maybe that's right. We're going to make iTunes and iPod really a platform to bring music and digital media to the whole world, not just to the Macintosh users, and that's more of a platform, an open -- more of an open platform position than a product position. And then he committed that we will make iTunes the best Windows app ever built. Still doesn't work quite right in my view, but anyway. Whereas Microsoft had always been much steadier, much wealthier, much more profitable, and things really changed for Apple after this point, and 2007, the iPhone came out, and then 2010, the iPad. In 2007, when the iPad came out, it was still kind of a closed system, and I wrote an article, the puzzle of Apple. Why do they keep introducing these closed products. I got hate mail. I actually thought my life was in danger from the Apple faithful. I said, Apple is a product company. They don't understand platforms, but I guess they had the last laugh in some ways, but the game's not over yet. The game's not over. Apple is still what we call kind of closed but not closed, whereas Microsoft has always been open, but not completely open, and we think that's kind of the better position to be. When did the light go on? For Jobs, the difference between a platform and a product, I don't think it was before 2003, and the Apple people argue with me over this. The Apple II was kind of a platform. He got software companies to write software, but it wasn't open. It was not easy to write for. Even the Mac, Gates made his SDK for DOS essentially free. Jobs charged I've heard as much as $20,000 for the SDK for the Macintosh. That's not an open -- that's not really an open-platform mindset. Grove didn't understand until 1990 the importance of the platform that they had created. He basically treated the microprocessor as a component. It was a component in the PC, and then he realized that component was feeding this enormous ecosystem and that if he changed the instruction set, moved to an incompatible technology, all that would disappear. He was overruled by his team, 1990. Gates got it immediately, when IBM appeared in 1980. He was lucky they appeared, but they came to him because he was the best at making languages for the personal computers, but he understood intuitively, immediately, the broader meaning, and I think this represented a platform position rather than a product position. Okay, I could go on, but I think this is a kind of a good place to stop, particularly since I'm at Microsoft, and I do think you guys understood platforms before anyone else, at least in the personal computer business. And some of the other things we talked about is the platform leader's dilemma. You have this enormous platform and annuity. What happens when things change? And they will change. It may take 30 years, but things eventually change, and how do you prepare an organization for a change like that? So we write about that, as well, and who did these guys choose as their successors is another issue, and why did they make those choices, and the big differences between Gates, Grove and Jobs on those decisions. So we write about all that stuff, try to understand the future, not just the past. Okay. So we have time for Q&A, right? I'm happy to stay, but any thoughts, questions? Yes. Do you need a microphone, or can he be picked up somehow? Okay. >>: If you guys can't hear me, I'll raise my voice, please. From what I understand, Steve Jobs, when the Macintosh was first launched, did not see it as a platform, and in 2003, he decided to open up iTunes to the world of Windows, and that ultimately allowed success. When the iPhone or the iOS App Store was launched in 2008, it just came out of the blue somehow. Do you think that Steve Jobs had the idea of the App Store the way it is now back in 2007? >> Michael Cusumano: No, it's the exact opposite, and this is pretty well documented. Jobs was opposed to the idea of an app store, and the same thing with the Mac. So the Mac shipped with applications, and there were companies making apps, but it was not a platform and ecosystem. It was done by contracts. So he wrote a contract with Bill Gates to write applications for the Mac, and he got other companies -- Adobe, for example, to also write some software. So it was not a platform, an ecosystem kind of dynamic. It was supplier kind of dynamic. And ultimately, information was released on Mac APIs, and some companies wrote applications. You couldn't build hardware for it. All of that was controlled. It was licensed very briefly. When it came to the app store, and here's the thing that Jobs was very consistent. He didn't want the iPod to be an open platform. He didn't want the iPhone to be an open platform. They came up with the app store kind of as a compromise, and it wasn't his idea. He was opposed to it. He thought he could contract for software, and then as he did with the Mac, very tightly control who wrote applications, who got access to SDKs and that sort of thing. There were some precedents for an app store. Palm had a little app store, and there were arguments. We heard from the Board of Directors, there were a number of arguments about this, but the app store, with tight controls over who got into the store and who didn't, was they thought a brilliant solution of keeping some control and controlling, again, how apps were written, user interface, user experience, but again, being closed but not completely closed. Jobs didn't like the idea, but he was overruled. And again, Jobs did not become successful until he allowed himself to be overruled. In his first iteration as CEO, he didn't allow himself to be overruled, so he was essentially fired, fired as head of the Mac project back in 1985, and then he quit the company. Then he failed with another company, NeXT, then hit a great success at Pixar and really learned about digital media from Pixar, and when he came back to Apple, he said, I don't want just a computer company. I want to think about digital media more broadly, and computers are in that role. So he learned tremendously over time. We have to give him credit for this growth and evolution. But he fought. He fought things that now define the success of Apple, opening up to Windows users, app store. Yes. >>: Do you think that with companies like Apple building their own chips and cloud companies like us building their own servers, that shift from horizontal to vertical is happening, and that Andy Grove might put the arrow the other way these days? >> Michael Cusumano: Well, there is a change going on, although I -- Andy might change the arrow, but at least for his company, I think it makes sense just to specialize. I don't think we want consumer products from Intel, and every time they've attempted to do that, they've failed. It's a different set of skills, so Apple can do it because I think they've always done it, from day one. They've really always tried to control everything, hardware, software. Now, designing their own chips is fine. They're working off of an ARM design. They have a perpetual license to it, so they didn't really invent the basic architecture that they're working with, and they -- so they can do it, and it's their distinctive edge to control that whole piece. Now, I know Microsoft has been moving in that direction and companies like Google and Amazon build their whole services. To me, that's a little bit different than entering the consumer market, where I think it takes a whole different set of skills, and I still think the idea of you enable an ecosystem and grow the whole pie with partnerships rather than try to control everything is the better way for the mass market. Now, remember, Apple quite a while ago, and this was Jobs' decision, decided they're not going for the mass market. They're going for the high end of the market. Who makes the most money in all these games? It's at least Apple, and will that last forever, I can confidently say no, it won't, because nothing lasts forever. But it's lasted a lot longer than I thought it would, but they're in that high-end segment, and usually, if you're retreating to the high end, there's nowhere to go after people come after you, but it's worked so far. >>: Do you see the same five lessons apply to companies like Google and Facebook? Google working on the data, search, and Facebook on the social media? >> Michael Cusumano: Yeah, so we spend some time at the end of the book talking about some of the modern generation of entrepreneurs and guys from Google, and certainly Mark Zuckerberg and even -- my wife is calling me, I think. Oh, no, somebody else, but no, we think these ideas apply very broadly. Look at the importance of platforms for these companies, this idea of also looking forward, reasoning back, each of these companies. Bezos at Amazon is kind of the same way. Again, they had a different -- this was a different generation, the Internet generation, but it's really very much a similar mindset. And some things will be different and you might have a more detailed or a different list to describe other things that other entrepreneurs do, but I think as a fundamental set of ideas, these are pretty important. And each of these companies, Google, Amazon, Facebook, have a very distinctive edge that comes from the founder. Again, that kind of personal anchor, but it's no longer personal. It's become organizational, and they've figured out a way to do that, and they've only been successful after they built the team, a management team. So they've made big bets, each of these companies, and they've used power, as well as cleverness. They've done it. >>: Was there a big company that came without having an individual with a specific anchor? >> Michael Cusumano: Well, entrepreneurial companies generally have someone at that point. When you look over multiple generations, it gets harder to see, but if you look at the founder or a transformative executive, I think you almost always find it. I've studied other companies in detail. Toyota is one, for example, and the Japanese we tend not to associate with strong individuals, but there were a couple very, very strong people that defined that company going back to the 1930s and then the '40s, 1940s and '50s, and it's still distinctive today, and that was centered around manufacturing and learning how to do things yourself, kind of reinventing process for what you needed to do. So I do think that's where great companies come from. They have an edge. Otherwise, you have companies that are formed around committees and the lowest-common denominator thinking. There was a question over here, too. >>: Okay, so strategy is also contextual, so your thoughts on Microsoft's move into hardware and into cloud computing, do you think that's a refinement of the strategy or a deviation from the strategy. >> Michael Cusumano: Well, cloud computing is certainly a deviation from the business model, but we've seen this for 10 or 12 years now. You don't have a choice, so it's another kind of a platform, but it's an evolution of the software product business model, and I've been writing about services now for 10 years, and I remember a conversation here with Microsoft, that the future is really going to be services in one form or another, and people saying, no, no, no, we're not going into services, over our dead bodies, and then figuring out, well, if they're automated services, then yes, maybe. An automated digital service is not that much different from a software product. That they can understand. So that I see. Going into hardware products, it doesn't make any sense to me. Well, I can understand the logic for it, but it kind of destroys the margins, and obviously, the motivation is from Apple. Apple did it by controlling all the components. The ecosystem isn't responding fast enough or creatively enough, and so Microsoft is trying to marshal some resources there and kind of stimulate the market around new designs, and if the market doesn't -- the ecosystem doesn't respond, maybe you need to do something. The Intel approach would have been to designate some companies as rabbits and kind of get them moving, rather than do the investment themselves. Now, at least Microsoft is not building billion-dollar factories -- at least I don't think. Are you? You're not, right? I just came from Boeing. I'm here because of a Boeing engagement. Those factories are expensive, right? You don't want to build factories where you're bending metal or building plastic, that kind of thing. >>: Eight-figure factories. >> Michael Cusumano: Eight-figure factories, okay. So if you can make the design and contract it out, maybe it's okay, but personally, I would not have done that. I do think it's a real serious deviation from the business model that has made Microsoft so successful, and even Google found it doesn't make much sense. Now, the Google guys are a little bit undisciplined in what they invest in, but even they couldn't make the hardware business work very well, at least up to this point. They haven't given up completely. >>: Do you have any thoughts on the rate of destruction or change now versus let's say 25 years ago. Do you think it has kind of ->> Michael Cusumano: I don't know. If I had a good answer to that -- I think the kneejerk response is to say things seem to be faster today. And actually, at one time, I created a chart. I was looking at product release cycles in software products, servers and other products, and it definitely get faster in the late '90s with Internet software releasing over the Web. You don't have to put software on CDs and in boxes and then on trucks and stores and all that kind of thing. But then things slowed down again, so I don't know. I don't know that disruption -- we've seen software as a service since 1999, cloud computing, whatever you want to call it. MSN in the Internet iteration goes back to 1995, '96, and so this stuff has taken a long time to germinate. It's not that fast, and that's why I think that you can kind of see -- you need to extrapolate from these things happening around you and kind of interpret what they can really mean if you built a company or a product around it. So I don't think things are changing all that fast, and having looked at it for 30 years. I don't know if you guys disagree, but certainly some cycles are much, much faster than they used to be. IBM used to work on five to 10-year timeframes, and Boeing still works on long timeframes, but they've cut it down. PCs, smartphones, software companies, definitely work on faster timeframes than they used to, but it's been fast for a while. I don't know that it's getting faster. >>: I think it's getting daily. >> Michael Cusumano: You think it's getting daily. Releases. >>: Correct. Part of Microsoft's DevOps vision, so certain parts of our business where we're delivering software as a service or just connected services, those are on a daily. >> Michael Cusumano: So you might be late coming to that, but if you look at Google or Amazon, they'll change their website daily multiple times a day, and they've been doing that for a long time. Years, right? >>: So it sounds like you're saying that strategy itself is affected by the methods that are in vogue. So right now, we have adaptive agile methods being adopted all over the place, and that has advantages and disadvantages, just like more predictive methods have advantages and disadvantages. I think that's what you're saying. So I'm just curious, do you see strategy -you've talked about technology changing, but is the act of strategizing changing over time? And what would it have been like for those guys if they were using more agile approaches back then? Would they have suffered for it, or would they have somehow been better off for it? >> Michael Cusumano: Well, strategy and strategy or strategic planning processes clearly has become more agile, to use that word. And we actually wrote about that in the Competing on Internet Time book in 1998, because at that time, Microsoft worked on essentially a three-year planning horizon, and they'd have one big annual meeting, and then Netscape appeared, and their ability to respond to Netscape was very weak. Now, they did respond, and I was actually here watching some of those responses, and heard about them afterwards. But they had to change the planning cycle, so actually, they put in a six-month review period. Now, I think they probably have the ability to respond to something in the environment is probably on a weekly basis within Microsoft. There's probably serious executive team meetings every week, right? Google moved to weekly meetings. I remember looking at Netscape in the 1990s. Their budgets were sixmonth chunks. They couldn't see farther than six months into the future. Microsoft was annual to three years. IBM was three to five years. That's what it took to build a new mainframe. So those kind of planning iterations did become more agile, and it has to do with the heartbeat -- we called it the heartbeat of the industry. Certain industries are much faster, and you can respond to that by your planning cycles. Now, you can't change your strategy every week, because that's like I remember using the analogy that came from another professor. It's like reevaluating your marriage every week. You can't do anything long term. No house, no kids, nothing. I've been in that situation, by the way. Right. >>: That's a chosen path in life, right? Younger people, like 30-ish? >> Michael Cusumano: Maybe, so you need to have ->>: No, in their relationships, that's how they operate. >> Michael Cusumano: But to operate a company that way is kind of destructive, because you can't do anything complicated and language term that way, so you need to balance. You need to be doing both. You need to be responsive in certain ways, but if you look at what Google does, they have a lot of long-term projects. Some may take 30 years to realize. I think they're building a spaceship to land on Mars, too, right, probably? >>: Sony supposedly has a 50-year business plan. Arie de Geus talks about companies in Europe that are working on a 100-year business plan. Clearly, they're not doing incremental for that big vision, long term. >> Michael Cusumano: It's kind of silly, I think, actually. Nobody knows what's going to happen 100 years from now, but you want to think, particularly in R&D. >>: It's a lighthouse on the horizon. You don't have to always ->> Michael Cusumano: But certain things, you can respond. You can do changes in features, for example, very quickly. You can make an acquisition or a hiring opportunity. Or you can start evaluating some big issues, and then have some information to make that decision when you have that monthly review point or six-month review point, but that is agile planning, and it's being aware. So I've also studied IBM on this. IBM again is a dinosaur, and then in many ways, that's an overused term. Again, these long cycles, and they realize that problem, and then after Lou Gerstner came in, by the late '90s and around 2000, they had put in different mechanisms for planning and responding, like teams had met monthly in addition to the annual planning cycle, and budgets that could be allocated with executive authority on this kind of monthly basis and ability to respond to acquisitions or experimental investments. So you can put in those kinds of mechanisms, and it is a form of agility. And this world you're in is fast enough that it requires that kind of agility, as well as some longer-term objectives. Okay, I think Amy's going to throw us out. >> Amy Draves: Not quite. I just have one online question for you, which is what are your visions for technology in the next five to 10 years? >> Michael Cusumano: What are my visions as far as technology? Well, I guess so I'm more a historian than I am a visionary. I am not a visionary, and I kind of tend to look back and reason forward, but one of the things that I really am struck with is autonomous vehicles and autonomous piloting. I was spending time at Boeing this week, and just the use of software in more and more contexts to automate more and more critical functions is clearly going to become a much bigger part of our lives, and that is one thread. The other thread that I've been doing little projects around is Internet of things or Internet of everything. As so many physical devices get sensors and can start generating data and we have analytics to deal with that, these are opportunities to create new kinds of platforms and applications, and we've been talking about that for a while, but many people believe it's very important. I see no reason to think that it's not going to be important, and it'll be connected to other things, like ubiquitous Internet and Wi-Fi accessibility, cheaper power or different sources of power to power all these devices around the world, Third World. But again, I think we have a reasonably good idea of what the future could be like in five to 10 years, and a lot of people are acting on that now, so I think it's not quite a Moore's Law situation, but I think the pieces are there that we can do that extrapolation and interpretation. It's just I don't think it's that unclear, particularly for people like you guys. It's what you do today and tomorrow is the critical thing. I just write books about what you guys do. >> Amy Draves: That's a great place to stop. Thank you so much. >> Michael Cusumano: Okay, well thank you all for coming.