FREE AS IN BEER

advertisement

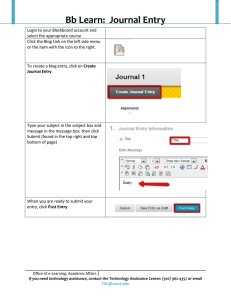

FREE AS IN BEER AND FREE AS IN SPEECH: PUBLIC SECTOR INFORMATION AFTER 450 DAYS OF OPEN GOVERNMENT INTRODUCTION Reading is a special pleasure for me. I have always loved books. Thousands line our walls, scores fill the bedroom, and there are always a couple piled on the bedside table. While I have struggled with the wilful suspension of disbelief required to watch a play, a book can absorb me in an instant. I’d like to say my tastes are eclectic – because it sounds so dignified – but, if the truth be known, I tend to survive on a diet of history, politics, science fiction and, especially, the American Civil War. It should come as no surprise then that I’ve also got a soft spot for libraries and librarians. In my first year at high school, I was a member of three libraries and used to borrow from each of them every Friday. While I still have every book I have ever bought, for a long time, I couldn’t afford to buy a lot and thus, even into my 40s, the local library was important to me. So, when offered the chance to speak to a group of librarians, I was more than willing. I figured that, even in a small way, I’d be able to pay back some of what has been given to me. In doing so though, I’m not sure that, on the face of it, my message is what you expect to hear – but more of that later. THE DECLARATION OF OPEN GOVERNMENT In July last year, the then Minister for Finance and Deregulation, Lindsay Tanner, announced the Australian Government’s Declaration of Open Government. The Declaration was an outcome of the Government’s response to the report of the Government 2.0 Taskforce that it had established in June 2009. The report, entitled “Engage: Getting on with Government 2.0”, covered a wide range of Web 2.0 matters. For clarity, let me briefly explain the difference between Web 1.0 and 2.0. Web 1.0 was about publishing information – mostly static and often in voluminous web sites, pages and pages of information, largely converted directly from previous brochures and similar documents. The result was an online library of information but devoid of most of the features that distinguish a good library – no indexing by subjects, no ready distinction between fact and fiction, lack of proper referencing – and certainly no librarians. Searchable it was and remains but through the use of text searching and without the benefits of the recognition of authority or reputation. Web 2.0 does not necessarily address these shortcomings but it introduces new features – chiefly collaboration. Through Web 2.0, governments can become involved in the three characteristics outlined in the Declaration – informing, engaging and participating with people, communities and businesses. In this discussion, I will be concentrating on the aspects of informing, declared as “strengthening citizen’s rights of access to information, establishing 2 a pro-disclosure culture across Australian Government agencies including through online innovation, and making government information more accessible and usable”. The Government’s commitment to informing is demonstrated by the passage of legislation reforming the Freedom of Information (FOI) Act and by establishing the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner. As the OAIC is represented at the conference by the FOI Commissioner, it would be presumptuous of me to dwell on this detail. Rather, I will confine my remarks to the manner in which this informing is being supported by the government’s information and communication technology infrastructure and the ramifications of this support for us and, perhaps, for you. FREE AS IN BEER If I learnt one thing in the Army, it was that free beer can result in many things – but chief among them was often a headache afterwards. The expectation that public sector information will indeed be free as in beer is growing, and with it, the possibility of a subsequent headache. This shouldn’t be seen as a criticism or complaint. It is, though, a realisation that this expanded access needs to be well planned and carefully executed so its enjoyment is not marred by the after effects. Agencies are necessarily required to consider how to present this information on line. This is a complicated question because it has many parts. Firstly, it consumes resources. While not prohibitive, the required resources are also not immaterial. Almost all public sector information starts its life in a computer friendly form. The ubiquitous Microsoft Office suite, in use on 84% of government personal computers, is most likely the tool de jour in 2011. But this has not always nor is it guaranteed to be always the situation. Even within that suite, the format used varies between versions. Although these differences are often not marked, especially in the eye of the reader, they generate quite a degree of discussion among the software aficionados. You might be surprised to learn that of the 1300 odd legitimate comments made on the AGIMO Blog since May 2009, almost 15% were made on one post about this one matter. Despite beginning in such formats, the subsequent official documents are usually the result of printing and signing. Sometimes there are hand written annotations. There are usually security classifications. Retention times vary. Document identification schemes vary significantly. All these factors mean that online access, if provided well, is a serious undertaking. Once upon a time, access to these documents would have been provided via online documents consisting of scanned images. Most of us can cope with this. Of course, sometimes the images are a bit blurry but we can normally work our way through them. Not everyone enjoys this ability. Yet, the beer has to be free for all. Accessibility is therefore an important facet of providing public sector information. The Australian Government has agreed to adopt the international World Wide Web Consortium’s Web Content Accessibility Guidelines Version 2.0 through a national transition strategy reaching the middle level standard (known as AA) by 2014. Using these guidelines, web content is required to be perceivable, operable, understandable and robust for all users. Progress towards this goal is 3 well underway. The AGIMO accessibility team has actually won a Vision Australia award for its work in this area. AGIMO’s developing practice is to publish our presentations like this one on our blog. As an example of accessibility, these guidelines will require us to present it in two formats, to ensure there are options for impaired readers. PowerPoint slides, if used, will need to have alternative text provided for each image so visually impaired readers can understand them. My staff will sometimes need to adjust the contrast in the text for similar reasons. Once used to these arrangements, they are not difficult to maintain but they do consume resources. More significantly, the conversion of legacy documents, not prepared with these requirements in mind, presents a considerable burden to agencies. Not all public sector information, also referred to as PSI, is about documents though. In its daily business, government produces a large number of datasets. Some of these, and their sources, are well known to all of us. The Australian Bureau of Statistics’ extensive statistical data range is provided free online for all those who are interested. Aside from their obvious value, they are often used for other purposes. For example, my favourite table 6345-5b, the quarterly Labour Price Index, is often referred to in government contracts as the means of applying annual cost increases for contractors. Not all datasets have this degree of reuse for government purposes. Take, for example, the National Public Toilet Map. Prepared as part of the National Incontinence Strategy, you might think that the data that supports the map would be of little enduring value. Well, flush that idea right out of your mind. The data.gov.au site now has over 700 government data sets available for reuse by interested citizens, businesses and communities. A range of applications have been developed to utilise this data, including two that utilise the toilet data. These applications haven’t been paid for by government or required particular support or resources. They’ve been developed by interested parties. Some may lead to commercial opportunities, others may not – but that isn’t the point. Having been created for one reason, there is no additional development required to present them for public consumption and little additional cost to make them available on the data.gov.au site. There have been some interesting legal issues to consider. To what extent should government warrant the accuracy of such information? Is there a requirement to update such information regularly, even if the reason for its original production is no longer relevant? Should there be limits as to how it can be used or with what other datasets it can be mashed up? Generally, these risks have been assessed as very low level. While Australia has yet to achieve the numbers of datasets available on similar sites in the UK or USA, the collection continues to grow. FREE AS IN SPEECH The second part of this dynamic duo of data is the concept of free as in speech. To make government data free in this way, we need to ensure it can be used by others without licensing restrictions. The Government, through the Attorney General’s Department, has amended the intellectual property regulations to ensure that the default license for government data and documents is an open license, typically the Creative Commons license CC-BY. While the previous crown copyright regime was rarely invoked, the new preferred 4 regime ensures that, with appropriate acknowledgement, those wishing to use PSI, for example, quoting from the budget papers, can do so freely and legally. This regime applies to websites just as it does to documents. Increasingly, government interaction is occurring online. Our research shows that the preferred channel for interaction with government for those who have access to the internet is the internet. Of those without such access, 30% would prefer to use it if they could. Overall satisfaction with online government services is also high – 86% reporting satisfaction. Increased use of the online channels does bring with it some particular issues. Earlier, I mentioned the AGIMO Blog. It is one of 35 blogs or websites supported on AGIMO’s govspace platform. This platform allows agencies to quickly develop and deploy a public consultation or collaboration site. For example, just last week, the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet deployed a Cyber White Paper blog to encourage public comment on this initiative. Supported by a Twitter campaign and a more traditional website, this multipronged strategy appears to already be attracting interest in what could be a somewhat dry topic. Maintenance of such a platform is relatively simple but it cannot be ignored. The govspace platform is receiving over 400,000 visits each month. Our AGIMO blog as I noted has had some 1300 legitimate comments made on the 140 odd posts published since its inception. However, there have also been 1400 advertising spam comments that we have had to manually delete and over 10,000 spam comments blocked automatically by our software. While these may seem alarming statistics, many of those manually blocked were made before we implemented a ‘CAPTCHA’ technique. This mechanism ensures that comments can’t be left by ‘bots’ but must be entered by humans. More interestingly though, despite having a liberal, post-moderation policy for comments and allowing hyperlinks to be entered as part of the comment, we have only had to delete 13 comments. Two of these were political comments made during the caretaker period, nine were identical and submitted as part of an ill-directed campaign (we showed how many there were but didn’t post them all), one was libellous and the last was silly and we blocked it to avoid embarrassing its author. We think this is a pretty good result, indicating that our audience is generally well-behaved and self-moderating. Of course, your mileage may vary and, yes, we are aware that government ICT management isn’t likely to be on the busiest shelves of your libraries. SO WHAT? This brings me to considering what effect this move online might have on your profession and the manner in which you assist your customers to access information, either from government or from other sources. I mentioned earlier that I have thousands of books on my shelves at home. I don’t have thousands on my iPad – yet. But I certainly have quite a few. The ability to purchase books cheaply and at that proverbial drop of a hat is changing business models and not just for book shops, small or large. 5 I presented at a conference last week on the use of ICT in supporting government service delivery. As I have discussed, shortly afterwards, we posted the presentation on the blog. A day or so later, a person with whom we worked on the Government 2.0 Taskforce posted a comment on that blog. He mentioned a book he thought I might find interesting and relevant to the presentation. I got around to reading his comment late that night. My interest was piqued and despite it being quite late, within a few minutes, I had purchased a Kindle edition and was reading it on my iPad. The book cost less than $10. In fact, in finding a legitimate copy, I had to scroll past several sites offering pirated copies for free. And it’s not just books. For the price of less than two hard copies of my favourite US produced current affairs magazine, I purchased an entire year’s subscription to read on the ubiquitous iPad – I even get notified by email when it is ready to download. I am sure your libraries offer online subscriptions to a whole range of specialist journals – but these get delivered to me so easily, it makes even remote online access to a library look inconvenient. So, if books are so cheap online that library access isn’t required, journals are so easy to access that the limitation on reading them is not cost but time, and a wealth of information is available at the touch of a (Google equipped) finger, what role is there for the librarian? I am sure this question must worry you from time to time. While nostalgia might keep some of us coming for a while, and, of course, there will always be some for whom a computer is a step too far or too difficult, these numbers are surely dwindling. I don’t know if there is a definitive answer or whether it really is a significant problem for you. But, on the off chance it is, allow me to finish by sharing with you how I see one potential future evolving. THE LIBRARIAN AS INFORMATION BROKER Navigating the plethora of information available online is a challenge for many people. So many options with so little to differentiate them means that finding the right answer is no longer a matter of searching for a needle in a haystack but, rather, searching for a single needle in a haystack-sized pile of pins. To torture the analogy somewhat further, some of the pins are very sharp and can actually damage, perhaps, badly, the unsuspecting searcher. What could an information professional do to assist here? On the demand side, assistance with efficacious search methodologies is clearly required. People may attend an ‘information place’ to seek such assistance but maybe a ‘click to chat’ mechanism on professional search sites might be useful. Whether that service was live or queued requests for asynchronous attention is a matter for further exploration. You probably do some of this already. However, I think there is more to be done on the supply side. All government departments produce a wealth of information and the obvious trend is to produce and publish more. While archivists can tell us how to file and store it, the need to open it up has produced a need for advice about how to present it to those who need it. I don’t mean in a graphic design sense but in a way that makes it easy to find what is required, arranged logically so it can be understood simply and authenticated in a way that allows the user to separate the digital wheat from the chaff. 6 The librarians of my youth helped me find Robert Heinlein, Isaac Asimov and Stonewall Jackson. Today, I think government needs assistance to ensure people, businesses and communities can easily find the information it must or should provide to them. Once again, we need your help.