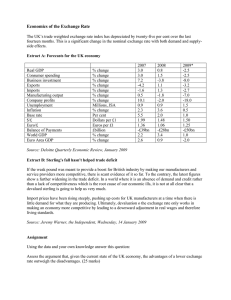

Laying the foundations for future prosperity: spending

advertisement

Address to the Corporate Members of the South Australian Centre for Economic Studies Laying the foundations for future prosperity: the longer-term challenges of managing government spending David Tune PSM Secretary Department of Finance and Deregulation Friday 19 August 2011 1 Thank you very much for the invitation to speak today. As a born and bred South Australian – but not one who supports either the Crows or the Power – it is always good to return to Adelaide for a visit. My topic today is a little dry. But I hope that I can bring it to life for you somewhat. It is certainly topical as the challenge of fiscal consolidation and sustainability of government finances is on the front pages of newspapers around the world at the moment and, dare I say, is likely to remain there for some time. The challenge of fiscal consolidation and sustainability It would be an understatement to say that recent years have been challenging times for governments. Recent volatility in world financial markets and concerns about debt in the US and Europe are reminders that there remain significant risks and challenges to address. Foremost amongst those challenges is the task of restoring sustainability to public finances. The Australian Government’s current fiscal strategy is to return the budget to surplus by 2012-13 following the large fiscal stimulus to buffer the economy from the effects of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and to build the foundations for maintaining a sustainable budget position over the medium to long term. Australia had the distinct advantage of entering the GFC in a very solid position. And, in the aftermath of the GFC, our public finances remain among the strongest in the world. Australian Government net debt is expected to peak at a little over seven per cent of GDP in 2011-12, around a tenth of the average net debt level of the G7 major advanced economies. The IMF forecasts that, while Australian Government net debt will decline to around 4½ per cent of GDP by 2016, average net debt levels of advanced economies will be close to 80 per cent of GDP. Just this week the World Bank President, Robert Zoellick, while reflecting on the ‘danger zone’ related to events in the US and Europe, has commented on 2 Australia’s very low debt levels, our past structural reforms, our open trade position and our favourable comparative position. Nevertheless, the Government’s task is a challenging one. Australia’s fiscal position is a lot healthier than that of most other advanced economies but despite that, as we know from the GFC, we are not immune from developments in world financial markets. Whilst events are still playing out, the most recent global financial turmoil has made Australia’s fiscal consolidation task harder. Moreover, like most other advanced economies, Australia faces emerging and long-term structural pressures such as population ageing. Again, Australia is better placed than most on that front. Nevertheless, medium to long-term pressures remain a significant challenge for Australia’s fiscal sustainability that will continue to require attention by government and increasingly also by the community. Despite these pressures, citizens’ expectations of government show no sign of abating and indeed they seem to be increasing at the same time as a large part of the population want reduced taxation (on themselves at least). Medium to long-term fiscal pressures in Australia So let me briefly run through the story surrounding the medium to long term fiscal pressures in Australia as set down in that bestseller - the 2010 Intergenerational Report (IGR). Since 2010, there have been several developments, including new policies, but the overall picture about structural fiscal pressures remains essentially unchanged. And I should mention that the story here relates to the federal sphere of government only. It doesn’t cover state government finances. The 2010 IGR projected that, over the next 40 years, the ageing of the Australian population will see the number of people aged 65 to 84 years more than double and the number of people 85 years and over more than quadruple. On current policy settings, this will significantly increase government spending, particularly in the demographically sensitive areas of age-related programs and health, which are projected to be the fastest growing categories of government expenditure. 3 The ageing of the population doesn’t only have implications for government spending. It will also have implications for economic growth and living standards, and for our capacity to pay for this additional spending. As the population ages, labour force participation is projected to fall because, as you’d expect, participation rates are lower among the older cohorts of the working-age population. This projected decline in workforce participation will reduce the potential growth rate of the Australian economy. Over the past 40 years, real GDP growth has averaged 3.3 per cent a year. The IGR projected real GDP growth in the next 40 years to slow to 2.7 per cent annually. Over half of this slowing can be directly attributed to the ageing of the population. The same demographic pressures driving the increase in government expenditure will also limit our capacity to pay for the additional expenditure. In 1970, there were 7.5 people of working age to support each person aged over 65. Now there are five. The IGR projected that by 2050 there will only be 2.7 people of working age to support each person aged over 65. Overall, the IGR projections show that, under unchanged policy settings, as government expenditure continues to grow and assuming revenue grows in proportion with GDP, the budget balance (excluding interest payments) would return to deficit around half-way 4 through the 40-year projection period, leading to a growing ‘fiscal gap’ – which by the middle of the century would amount to around 2¾ per cent of GDP. The implication is clear. If, over the long term, existing expenditure programs were to continue unchanged and GDP were to grow at the projected slowing rates, at some point Australians would need to pay higher taxes for government to ensure a sustainable budget position. Drilling down a bit further, health care and social security and welfare are the largest areas of government spending currently. Around one third of total spending is payments for social security and welfare. These payments provide income support and services to the aged, assistance to the unemployed, people with disabilities and their carers, families with children and veterans. It is in these payments that the effects of demographic changes will have their greatest impact. Indeed, even before the impact of demographic change, these payments have been increasing both in absolute terms and as a share of total expenditure. As a share of total spending, they have risen from around 28 per cent of the total in 1980-81 to one-third in 2010-11. In terms of percentage of GDP, social security and welfare has risen from 6½ per cent of GDP in 1980-81 to around 8½ per cent of GDP in 2010-11. 5 6 As shown on the left hand side of the slide, it is projected to increase further to close to 10 per cent of GDP by 2049-50. Turning to health care, this accounts for 16.3 per cent of total government expenditure. Health expenditure has increased from around 2½ per cent of GDP in 1980-81 to around four per cent in 2010-11. A further large increase to around seven per cent of GDP is projected by the middle of the century – a faster rate of increase over the next 40 years than in spending on social security and welfare. It is worth also looking at some of the key components of these areas of government expenditure, as well as some other areas of government activity. Assistance to the aged Clearly, assistance to the aged will be significantly impacted by the ageing of the population. Both expenditure on age related pensions and expenditure on aged care have increased as a proportion of GDP, and further significant increases are projected over the next 40 years. 7 In addition to being the largest component of social security spending (accounting for almost 40 per cent of the total), assistance to the aged is also the fastest growing. Age pension payments, the largest form of assistance to the aged, grew at an average annual rate of 7.4 per cent (a little over four per cent in real terms) in the ten years to 2010-11. While growth in average payments (i.e. increases in the adequacy of the aged pension) explains most of this increase, increases in recipient numbers have been, and will continue to be, an important source of growth. Recipient numbers have increased from 1.8 million in 2000-01 to 2.2 million in 2010-11, an increase of a little over two per cent annually. And they are projected to grow significantly faster in the decade to 2020-21 – at a rate of a little over three per cent annually. To put that in a broader context, these are faster rates of increase than population growth over the two decades to 2020-21 of around 1½ per cent annually. The projected continued ageing of the population means that, under current policy settings, including importantly the settings about what is the right division between public and private spending, assistance to the aged will be an area of increasing spending pressures. The IGR projects that the cost of aged pensions per person (in 2009-10 dollars) will more than double between 2009-10 and 2049-50. As a proportion of GDP, aged pensions are projected to increase from 2.7 per cent of GDP to 3.9 per cent of GDP. In light of this, governments have recognised that sole reliance on publicly funded pension payments are not sustainable in the long run and have introduced reforms to increase selffunding of retirement. The most recent example of this is the decision to raise the superannuation guarantee to 12 per cent by 2019-20. Of course, initiatives to encourage self-funding of retirement are not without cost to the budget. Most individuals are presently able to access superannuation concessions, a full or part pension and/or other concessions as well as generous taxation arrangements. These concessions will become increasingly costly to the budget as the population ages, threatening fiscal sustainability. The Henry review suggested measures to improve the long-term sustainability of the retirement income system. These include tightening 8 eligibility for the pension and increasing the superannuation preservation age to the age pension age. 9 Another component of assistance to the aged that will come under increasing pressure is residential and community care. The Australian Government subsidises aged care significantly. Subsidies are paid directly to aged care homes and depend on residents’ care needs (high care or low care), income and assets. Overall, the Australian Government contributes approximately 70 per cent of the cost of residential aged care. Expenditure has been kept in check to some degree by changes to funding arrangements in the late 1990s which have resulted in residents paying a greater share of their care costs through accommodation fees and bonds. Second, governments have capped the number of subsidised aged care places at 88 places per 1,000 people aged 70 and over. And, third, much greater emphasis has been placed on home and community care over the past two decades to help people stay in their own homes for as long as possible. Notwithstanding this, aged care spending is projected to be the fastest growing category of spending, with a four-fold increase over the next four decades in terms of real spending per person. Clearly an increase of this magnitude is not sustainable. Addressing these pressures is not just a question of the quantity and type of aged care services. It will also require a re-evaluation of who pays for health and aged care services and whether more of the burden should fall on those users who have the capacity to contribute more than at present. In particular, there will be a need to address whether the comfortably off in the community (and their inheritors) should continue to have their health and aged care services subsidised to the current extent by taxpayers, many of whom are in less fortunate circumstances. 10 As noted by the Productivity Commission in its recent report, Caring for Older Australians, “… service delivery must become more effective and efficient, but this will not, in itself, sufficiently reduce the rate of growth of public expenditure”. In that report, the Productivity Commission proposed a number of reforms. These are aimed at providing older Australians with greater flexibility and choice. The Commission also recommended, subject to safety nets for those of limited means, that older Australians make a greater personal contribution to the costs of their care and accommodation. The Government released the report last week for public consultation. It is clearly a sensitive issue but is a debate worth having. Health Turning back to health, one in six dollars spent by the Commonwealth is related to health care. This covers funding for Medicare, the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, the Private Health Insurance Rebate and payments to the States and Territories to help meet the costs of operating public hospitals. Expenditure on health has been growing more rapidly than GDP and overall government expenditure over the past decade, averaging around five per cent in real terms. According to the 2010 IGR, this trend is expected to continue with average real growth in health expenditure of 4.5 per cent over the next 40 years. While drivers of this growth have varied from program to program, some factors are common: population growth, particularly in recent years, has increased overall demand for health services; population ageing has increased the proportion of the population in elderly age cohorts which consume a disproportionate portion of health care services; and increased medical and pharmaceutical costs associated with more modern procedures and drugs have increased the per capita cost of health care; in addition, pharmaceutical costs have been significantly increased by extensions to the concessional category (for example for a large number of seniors who were previously ineligible). 11 A number of major health programs have seen, and will continue to see, strong expenditure growth, including in particular the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS). Over the period from 2000-01 to 2009-10, real expenditure growth for the MBS and PBS averaged 5½ to six per cent annually. Spending on the MBS and PBS is affected by population growth and, to some extent, by the ageing of the population. However, spending is also influenced by developments in health technology and listings of new products and services. These non-demographic influences are stronger than the demographic impacts. Payments to the States and Territories for hospitals will grow strongly (at around eight per cent per annum in real terms from 2014-15), in large part due to volume growth and the Commonwealth’s commitment to meet 45 per cent of the growth in the efficient price of hospital services, rising to 50 per cent of the growth from 2017-18. From 2000-01 to 200910, growth in health payments to the States and Territories averaged 3.6 per cent per annum. These trends are expected to continue over coming decades. Australian government spending on health is projected to increase as a proportion of GDP from four per cent in 2009–10 to a little over seven per cent in 2049–50. Given these pressures, it will be important to ensure that the health system delivers value for money. Family payments All of this sounds a bit grim from a fiscal sustainability viewpoint. However, there are a few things that help a bit. Part of the reason that the population is ageing is that our fertility rate has declined over time. In short, there will be fewer children as a proportion of the population in future. 12 This helps us in two ways: First, through assistance for families; and Second, through education spending. Australian Government spending on families is around 2.7 per cent of GDP, which is above the OECD average of two per cent. Australia also provides the highest in-work payments to low income families across the OECD. But over the long term, family payments are expected to decline to around 1¼ per cent of GDP as a result of a decline in average family size. Education On education, around eight per cent of government spending is allocated to education. This expenditure supports government and non-government schools, higher education, vocational education and training. Education spending is projected to grow gradually over the next 40 years, after the initial phase-down of the Government’s stimulus through the Building the Education Revolution package. Following the completion of the stimulus spending in 2010-11, spending on education as a proportion of GDP is projected to rise from 1.7 per cent in 2012–13 to 1.9 per cent by 2049– 50. In part, this growth reflects policy decisions, including the introduction of uncapped university places from 2012 along with increases in per place funding. 13 Taking all this into account, the IGR suggests that, if nothing changes, the picture will look like this. Spending per person will increase from around $15,000 per person to over $25,000 by 2049-50. Increasing Participation and Productivity So what do we do about all this? Is there a way through? The answer lies in what are called the “two Ps” – increasing labour force participation and productivity — so as to raise economic growth above what it would be otherwise and thus increase the capacity to pay (through the generated increased revenue) for higher levels of government spending. As I noted earlier, as the population ages, labour force participation is projected to fall. Offsetting the impacts of the ageing population on participation requires carefully designed income support and taxation arrangements that minimise disincentives to actively participate in the labour market. 14 In particular, the relatively high level of some welfare payments, together with withdrawal rates which create high effective marginal tax rates when paid employment is undertaken, can provide a disincentive to participate in the labour market. Encouraging greater workforce participation is also necessary to offset the impact of the ageing population which is expected to lower average participation rates. The ‘Building Australia’s Future Workforce’ (BAFW) package announced in the 2011-12 Budget is the most recent government initiative to increase workforce participation. The package aims to increase participation rates amongst people most at risk of being marginalised from the labour force. This includes mature aged people, the long-term unemployed and people with a disability. Meeting the challenges of the future will also require an improvement in productivity growth. In large part, Australia’s welfare depends on its levels of productivity. Productivity performance is a key determinant of living standards and historically has provided the largest contribution to growth in real GDP per capita. Productivity improvements will also better enable government to responsibly and sustainably deliver services to those most in need and will build resilience in the face of future economic challenges. Following a comprehensive program of microeconomic reform (including trade liberalisation, taxation reform and industrial relations reform), productivity surged in the 1990s. However, productivity growth has slowed recently to less than half the growth rate of the 1990s. Addressing this slowdown will be an important challenge for governments. 15 Managing Community Expectations Aiming for stronger economic growth will take us only part of the way in meeting rising community expectations and tackling growing fiscal pressures. As I mentioned, advanced countries are facing ever rising community expectations about the range and extent of services and support that governments provide. At the same time, most people are understandably reluctant to pay more tax. Quite rightly, there is an expectation of good quality and efficient public service provision. Governments are also expected to support a strong economy with the right incentives for effort and encouragement of sustainable growth in living standards. In addition, many within the community have a view that governments should take steps to lessen disadvantage and inequality, providing people with opportunities and delivering or facilitating the kinds of public goods and services that people need that can’t be delivered by the private sector alone. These are all admirable goals, and governments should strive to meet them. But the reality is that governments have limited (taxpayer-funded) resources. Trade-offs are therefore inevitable. Fundamentally, governments have to make choices on behalf of their constituents. Indeed, if high priority new needs or increased pressures emerge, then, in the absence of higher taxation, some things that governments are doing or supporting now might have to be scaled down or allowed to grow at a slower rate, or simply discontinued. 16