Market Definition as a Problem of Statistical Inference

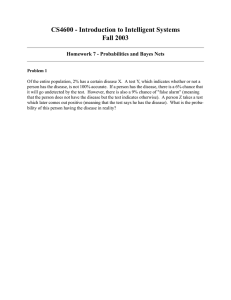

advertisement