Running head: PSYCHOLOGY OF COMBAT AND THE LAW OF WAR 1

advertisement

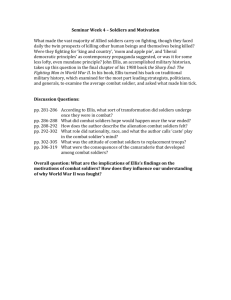

Running head: PSYCHOLOGY OF COMBAT AND THE LAW OF WAR Understanding the Psychology of Combat in the Law of War Jacob S. Burns Weber State University 1 PSYCHOLOGY OF COMBAT AND THE LAW OF WAR 2 Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………….3 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………...……4 Section 1……………………………………………………………………………………...….4 Section 2…………………………………………………………………………………………9 Section 3………………………………………………………………………………………..14 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………..19 Appendix A…………………………………………………………………………………….20 Appendix B…………………………………………………………………………………….22 Appendix C…………………………………………………………………………………….23 References……………………………………………………………………………………...25 PSYCHOLOGY OF COMBAT AND THE LAW OF WAR 3 Abstract This paper presents information to facilitate the understanding of the psychology of engaging an enemy in combat, in accordance with the rules of engagement (ROE) to uphold the laws and regulations of war. I will specifically discuss the psychology of engaging an enemy in armed conflict, to include: training and preparing for war, how a person can kill, and any repercussions that occur from their conflict. I will incorporate this into what rules of engagement are, how they play into the laws of war, and their specific importance. The history of the law of war, its regulation, and punishments affixed will be included. It is also important to discuss the roles of authority and obedience within the topic, and this too shall be accomplished. Keywords: rules of engagement PSYCHOLOGY OF COMBAT AND THE LAW OF WAR 4 Understanding the Psychology of Combat in the Law of War Introduction This paper will delve into understanding the psychology of engaging an enemy in combat in accordance with the rules of engagement while upholding the laws and regulations of war. The purpose for this project is to better inform and teach junior cadets in Weber State University’s Army ROTC program about the psychology of combat in relation to the law of war. Doing this will help them prepare for their roles as United States Army officers. In order to fully cover this subject I plan to discuss it in three sections. The first section will be about the psychology of combat. This section will include: the physiological response to the stress of combat, and how our mind reacts; the effect of training in preparing soldiers for combat; the role that proximity plays in engaging an enemy; how a person can end another’s life; and finally, the residual effects that combat leaves on people. The second section of this paper will go over the law of war: to include its history, how it is regulated and punishments associated with it, and how rules of engagement help to uphold the law of war. The third and final section of this paper will incorporate information from the first two sections and will focus on authority and obedience in relation to this topic. Section 1 “The starting point for the understanding of war is the understanding of human nature” (Marshall, 1947). Combat has been deemed as something that is not for the faint hearted. It is dangerous, stressful, and tough. There are atrocities that are committed more often than they should be. How a person reacts to this harsh environment is subjective to each individual. However, many studies reveal how individuals may react to these situations. Particularly I will focus on how the mind reacts to combat. PSYCHOLOGY OF COMBAT AND THE LAW OF WAR 5 Combat is undoubtedly one of the more stressful environments that a person can face. Stress results from a reaction to a stimulus, which most commonly results from the environment that a person is in. A person’s body responds to stress through the sympathetic nervous system and activation of the fight-or-flight response, which is part of the autonomic nervous system or “ANS”. This is an automatic reaction that the body goes through to increase survival. Although it was originally noticed in animals, humans have been found to react in similar ways as they had to make a decision of what to do when encountering a perceived threat or dangerous situation. The hypothalamus delivers this perception to the nervous system and in turn, the secretion of hormones begins: specifically, epinephrine, norepinephrine, and cortisol (Olpin). Once these hormones have been secreted the body is then enabled to have more speed, strength, and power than it usually does. Having this physical boost prepares the body to react to a stressor, such as combat, by enabling an individual to fight back or flee the situation. The hyperarousal that takes place in the fight-or-flight response has also been known to produce an alternate response. This third response is to “freeze”. This is could be described as someone completely locking up and freezing. To add on to the theory of the fight-or-flight-or-freeze response, Lt. Col. Dave Grossman added other responses that are commonly seen. Specifically when people are forced to react in a combative environment where there is possible physical harm from an enemy combatant. He theorized that there are four possible responses: fight, flight, posture or submit (Grossman, 2009). The fight-or-flight responses are the same as before but “posture” is the response that is commonly displayed in combat where soldiers act or pretend that they are fighting back but in reality are missing the enemy on purpose as to not kill another person (Grossman, 2009). There are many examples throughout history of posturing from the Civil War through both World Wars and up to the Vietnam War. Many accounts claim that there PSYCHOLOGY OF COMBAT AND THE LAW OF WAR 6 were a very low percentage of soldiers who actually fired their weapons at the enemy in World War II (Marshall, 1947), and if they did, they were posturing. Upon further investigation, the actual percentage of posturing soldiers has been disputed by many scholars, but it still remains as an available and very possible response to conflict (Grossman, 2009). The response to “submit” to an enemy force or combative situation is more commonly viewed as surrender. “Submission is a surprisingly common response, usually taking the form of fawning and exposing some vulnerable portion of the anatomy to the victor, in the instinctive knowledge that the opponent will not kill or further harm one of its own kind once it has surrendered (Grossman, 2009).” Although the posturing and submitting of soldiers has diminished more recently with modern training, which will be discussed in more detail later in this paper, it is still an available response. In sporting events coaches will have players on their teams “practice like they play”. Similarly in the military commanders would have their soldiers “train like they fight, and fight like they train.” Regardless of what you are trying to improve, the amount of success improves with practice. And so it is natural for soldiers to continuously drill and train to improve and learn their duties. Learning is defined as “a systematic, relatively permanent change in behavior that occurs through experience” (King, 2013). Although the military uses many forms of training to help individuals learn, much training is completed with the use of associative learning which “occurs when we make a connection, or an association, between two events” (King, 2013). To learn specific associations between events is where conditioning takes place. “One of the most powerful examples of the military’s success in developing conditioned reflexes through drill can be found in John Masters’s The Road Past Mandalay, where he relates the actions of a machine-gun team in combat during World War II: PSYCHOLOGY OF COMBAT AND THE LAW OF WAR 7 The No. 1 [gunner] was 17 years old – I knew him. His No. 2 [assistant gunner] lay on the left side, beside him, his head toward the enemy, a loaded magazine in his hand ready to whip onto the gun the moment the No. 1 said “Change!” The No. 1 started firing, and a Japanese machine gun engaged them at close range. The No. 1 got the first burst through the face and neck, which killed him instantly. But he did not die where he lay, behind the gun. He rolled over to tap his No. 2 on the shoulder in the signal that means Take over. The No. 2 did not have to push the corpse away from the gun. It was already clear. The “take over” signal was drilled into the gunner to ensure that his vital weapon was never left unmanned should he ever have to leave (Grossman, 2009).” The conditioning that took place for this gunner team in World War II shaped both their conscious and unconscious actions. In learning there are two types of conditioning; classical and operant, both of which are used in training soldiers. Operant conditioning or instrumental conditioning is defined as “a form of associative learning in which the consequences of a behavior change the probability of the behaviors occurrence” (King, 2013). I believe that operant conditioning is used more heavily as it relies on rewards and punishments and better explains voluntary behaviors. Military training is packed full of rewards and punishments, whether they are real or imagined. The power of consequence in determining behavior is an essential characteristic in operant conditioning for military training, specifically for combat. In every time period, soldiers have been trained and retrained. In the Civil War soldiers were trained to load their weapons and shoot as fast as possible in order to cause more causalities to their opponents (Grossman, 2009). However, shooting accuracy and target practice was not implemented in training regimes until the end of the 1800s and start of the 1900s (Emerson, 2004). With the development of better weapon systems there had to be better PSYCHOLOGY OF COMBAT AND THE LAW OF WAR 8 training to have success. Marksmanship and target practice became a high priority. Initially targets used in training had a bull’s-eye centered on them. Studies indicated that a low percent of soldiers would actually fire their weapons at the enemy (Marshall, 1947). Initiatives were made to change the standard of marksmanship and the customary targets were changed from the bull’s-eye to a silhouette of another person (Williams, 1994). This change in training was made to better prepare and condition soldiers to engage the enemy. The voluntary behavior of shooting a person in real life has become much easier for soldiers with the changes in training. The proximity in which an individual engages the enemy is an important factor in the effect of combat on an individual. Not only does the physical distance of the enemy matter in engagements but so does the emotional distance. As the distance from the enemy increases, the resistance to kill them functions inversely by decreasing (Grossman, 2009). In looking at the spectrum of distance killing on one end there is bombing (from aircraft, ships, artillery, etc.) where there is no interaction with the enemy. On the other end of the spectrum there is killing in hand to hand combat. Once you have direct interaction with a person you typically have more aversions to doing harm to them. It becomes more possible to view them as humans; perhaps your opponent is someone’s mother or father, son or daughter, or spouse. You could begin to empathize and sympathize with them and their situation, and see the similar positions that you are each in. Killing then becomes much more difficult. Combat takes its toll on soldiers and civilians alike. However, experiencing combat first hand would be considered a traumatic event and could result negatively. “A traumatic event is one in which individuals are exposed to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violation” (Comer, 2014). There are two stress disorders that are most commonly associated with combat; acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). During World War I it was called “combat fatigue” and during World War II and the Korean War it PSYCHOLOGY OF COMBAT AND THE LAW OF WAR 9 was referred to as “shell shock” (Comer, 2014). It was not until after Vietnam that these stress disorders were identified (Comer, 2014). Symptoms for both acute stress disorder and PTSD include: re-experiencing the traumatic event through thoughts, memories, dreams, or flashbacks; avoidance of activities that remind of the event, or related thoughts, feelings, or conversations; reduced responsiveness or separation from their environment, people, or loss of interest in activities that were once enjoyed; increased arousal, negative emotions, and guilt resulting in trouble concentrating, sleep problems, anxiety, anger, or depression (Comer, 2014). Because the symptoms of both disorders are the same the divisor of the two is time that the symptoms last. If they “begin immediately or soon after the traumatic event and last for less than a month, DSM-5 (the most recent Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) assigns a diagnosis of acute stress disorder. If the symptoms continue longer than a month, a diagnosis of PTSD is given” (Comer, 2014). Section 2 International laws are intricate and can be difficult to understand. Therefore, this section will provide an overview to increase understanding of this topic. Specifically laws of war are both as important and complex as the laws that regulate our own society. Similar to the origin of our governing laws, the laws of war have developed from religion, culture, policy, traditions, and events. Some of the earliest examples of the law of war that exist may come from the bible and other scriptures. “For example, in the Bible, Goliath suggested that a contest between two champions would be used instead of using two armies. Thus: ‘If he be able to fight with me, and kill me, then we will be your servants, but if I prevail against him, and kill him, then ye shall be our servants and serve us’” (Gillespie, 2011). Although there were traditions of what was acceptable in war, nothing was formally published about the law of war for centuries. As it is in society, laws are made usually as the result of something that has PSYCHOLOGY OF COMBAT AND THE LAW OF WAR 10 happened or was happening which was seen to be unacceptable. Many nations did come up with actions which they saw both as acceptable and unacceptable. However, on an international scale, laws and treaties of war were essentially devoid until the mid-1850s when privateering was abolished. Even then if there were international laws established, it was hard to enforce them. Once modernization began many more laws came in to existence, most notably were the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 which largely discussed what was proper in warfare in regards to the use of weapons (Crowe, 2009). The League of Nations can be identified as the first international organization whose principal goal was to maintain and enforce world peace (Crowe, 2009). Established at the end of the First World War, the League of Nations resolved some territorial disputes and minor conflicts. One of its primary tasks was to enforce the disarmament of countries whose militaries were getting too large (Crowe, 2009). The League failed to accomplish its goal of world peace when World War II erupted across the globe. There were apparent improvements that needed to be made in an international organization and so the United Nations came into existence at the close of the Second World War to help piece the world back together. Having a coalition of more countries helps to increase awareness and share opinions of international matters, which is one reason why the League of Nations was unsuccessful (Crowe, 2009). With obvious atrocities having been committed during World War II, the United Nations established the International Military Tribunal (IMT) which conducted the Nuremburg Trials and identified its “right to try individuals for three crimes plus conspiracy to commit such crimes: Crimes Against Peace, War Crimes, and Crimes Against Humanity” (Crowe, 2009). These trials were perhaps the most important trials in history that established international law of war, set a precedent for the proceedings of hearings, as well as convictions for crimes. In the opening statement to the court in the Nuremburg Trials, Judge Jackson said: PSYCHOLOGY OF COMBAT AND THE LAW OF WAR 11 “The privilege of opening the first trial in history for crimes against the peace of the world imposes a grave responsibility. The wrongs we seek to condemn and punish have been so calculated, so malignant and so devastating, that civilization cannot tolerate their being ignored because it cannot survive their being repeated” (Crowe, 2009). Those that were involved in the proceedings understood the consequence that would result from the trials. The seven principles established as a result of the Nuremberg Trials were to be used as guidelines in determining what constitutes a war crime1 (International Law Commission, 1950). In 1948, the UN outlawed genocide and broadly defined it as “any act designed to destroy, in whole or part, a national ethnical, racial, or religious group” (Crowe, 2009). The Nuremberg Trials were a huge step in international law and the law of war but they were not enough. There was still a need to address the rising concern of overall humanitarian actions of governments and militaries. The Geneva Conventions at the conclusion of World War II in 1949 did just this (Geneva Conventions). These conventions laid out the first laws and regulations for humanitarian treatment during war. In four separate conventions the treatment for following were discussed in detail: the wounded and sick in armed forces in the field; the wounded, sick and shipwrecked of armed forces at sea; prisoners of war; and rights of civilians (Geneva Conventions, 1949; 1977; 1993; 2005). There were also additional protocols which were introduced with time to account for changes in technology and warfare2 (Geneva Conventions, 1949; 1977; 1993; 2005). Currently, the International Criminal Court or ICC has jurisdiction over war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide (Crowe, 2009). Military law in the United States is enforced and punished through The Uniform Code of Military Justice or UCMJ. 1 2 See the attached principles in Appendix A A full list of conventions and protocols can be seen in Appendix B PSYCHOLOGY OF COMBAT AND THE LAW OF WAR 12 Although these laws and regulations were made in response to more recent events and conflicts, they were long overdue. Typically when a person mentions the topic of war crimes or genocide we are quick to remember World War II and the crimes committed by Nazi Germany. But war crimes and genocide had been happening for centuries before that time and all around the world (Crowe, 2009). In almost any region or country of the world, it is likely that there have been war crimes of one type or another that have been committed. In order to help prevent war crimes and other improper actions many countries have implemented Rules of Engagement or ROE. “ROE are directives issued by competent military authority that delineate the circumstances and limitations under which U.S. [naval, ground and air] forces will initiate and/or continue combat engagement with other forces encountered” (United States Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2005). There are common international ROE which are issued by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization or NATO. These ROE are typically adhered to by host nations who work in conjunction with NATO. Other ROE are dictated by commanders of certain conflicts which come down from the President and Secretary of Defense. Standing rules of engagement or SROE are a base which are always applicable regardless of a specific mission. Some SROE would incorporate self-defense (to include: the inherent right of self-defense, national selfdefense, collective self-defense, and mission accomplishment v. self-defense), hostile acts, and hostile intent (United States Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2005). There are also mission-specific ROE that dictate how solders may act only on a specific mission. In order to more easily apply and remember ROE soldiers are given ‘ROE Cards’ which clearly display what soldiers are and are not allowed to do3 (United States Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2005). ROE typically change over time and are influenced by national political policies. For example, stricter, or more restrictive, ROE have been implemented more in recent years as the combat has been drawn down in the Middle East for U.S. forces. The increase in strictness can hinder soldiers in their operations by 3 An example ROE card is attached in Appendix C (United States Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2005) PSYCHOLOGY OF COMBAT AND THE LAW OF WAR 13 not allowing them to use force when it would be beneficial and perhaps save lives and have mission success (Scarborough, 2013). In more recent years, ROE have complicated the jobs of soldiers. The modern battlefields that soldiers are currently on are much more complicated than they were in years past. Frontlines are not as easily distinguished, nor are the actual soldiers that we face. It was apparent in the Vietnam War as well as our current conflicts in the Middle East with our fight on terrorism. A modern example of the applicability of ROE in preventing war crimes can be taken from the account of Navy SEAL Marcus Luttrell in his book titled ‘Lone Survivor’. This book details his recollection of service in Afghanistan with SEAL Team 10. In the book Luttrell describes a dilemma he and his team face during a mission. They had a mission to kill a specific Taliban leader in the area when they were found by some goat herders. They had no way of knowing whether or not these goat herders were regular civilians or if they were in fact the very enemy they were fighting. The book details what his team decided to do. If by some means of their actions they killed these goat herders, either by their own hands or by exposure to the elements from detaining them, they would be breaking the ROE and have committed a war crime (Luttrell, 2007). However, if they let the goat herders go free, their mission would very well become compromised and their lives placed in immediate danger. They chose to let the herders go, and as a consequence, Taliban forces attacked their position and many Americans lost their lives. In further considering combat in general there are a few important principles in the Law of Armed Conflict or LOAC which govern actions of soldiers in the United States: military necessity, distinction, avoid unnecessary suffering, and proportionality (United States Army, 2007). “Military necessity requires combat forces to engage in only those acts necessary to accomplish a legitimate military objective” (Powers, 2013). This helps to limit any collateral PSYCHOLOGY OF COMBAT AND THE LAW OF WAR 14 damage that may take place in combat. “In applying military necessity to targeting, the rule generally means the United States Military may target those facilities, equipment, and forces which, if destroyed, would lead as quickly as possible to the enemy’s partial or complete submission” (Powers, 2013). Distinction is termed to help the discrimination of civilians from soldiers. The idea behind distinction is to only engage combative enemy soldiers. The Geneva Conventions help to clarify what actions are appropriate for each distinct individual whether they are a civilian, combatant, noncombatant, prisoner of war (POW), or injured or wounded personnel. “On some contemporary battlefields, enemies may try to exploit this principle by fighting in civilian clothes and using civilian or protected structures” (United States Army, 2007). The third principle of avoiding unnecessary suffering in the LOAC is used to help soldiers to make the distinction in what is necessary to win the fight or save another soldier’s life and not killing or destroying what is unnecessary (United States Army, 2007). The final principle of proportionality is very important for soldiers and leaders to gauge the correct response of force in a situation. “The military necessity of the target must outweigh the collateral damage caused by the commander’s act” (United States Army, 2007). Not only is it unacceptable but it also could have legal consequences under the UCMJ if disproportionate force is used on a combatant. Section 3 Having already gone over some of the psychological aspects of combat and the background of the law of war it may be easier to make connections in the two of them. Specifically, in this section, I would like to concentrate on the use of authority in combat. “Authority is the delegated power to judge, act, or command. It includes responsibility, accountability, and delegation” (United States Army, 2007). Stanley Milgram, a psychologist, conducted many experiments about obedience to authority. He found that people as a whole are PSYCHOLOGY OF COMBAT AND THE LAW OF WAR 15 very willing to comply with authority figures. In his famous experiment there would be three individuals involved: the authority figure, the participant as a teacher, and a student who was actually a confederate, or actor, and part of the experiment. The participant was instructed by the authority to administer an electric shock to the student if he or she had an incorrect response to a question (although the student never actually was shocked but would just act as if he or she was shocked). Each question wrongly answered would elicit an increasingly strong shock from 15 volts, labeled as “slight shock,” to 450 volts, labeled as “XXX” (Kassin, Fein, & Markus, 2011). The student and teacher could not see each other but could communicate and hear each other. The student continually gave incorrect answers and the teacher continually administered shocks. The student would scream and cry for the teacher to stop shocking him or her but the authority figure would urge the teacher to continue even until the student was quiet, perhaps dead. Sixty-five percent of all the participants administered the lethal shock of 450 volts (Kassin, Fein, & Markus, 2011). In his experiments Milgram found that several factors were influential in participants’ compliance: the authority figure, the proximity of the victim, and the experimental procedure (Kassin, Fein, & Markus, 2011). Indeed many people will follow orders given to them without even second guessing whether they are doing something that is morally correct. To better understand this blind obedience that people engage in we must better understand authority powers. Social psychologists define power as having a certain attribute which gives a person more influence over another (Kassin, Fein, & Markus, 2011). In reality there are five separate types of authority powers; each one of these five powers of authority influence people’s obedience. Obedience is defined as “behavior change produced by the commands of authority” (Kassin, Fein, & Markus, 2011). The first type of authority power is corrosive power, which is defined by someone having the ability to punish another. The second is reward power, the PSYCHOLOGY OF COMBAT AND THE LAW OF WAR 16 opposite of corrosive power, giving a positive reinforcement. Third, is expert power, which results from experience or education such as a professor or doctor. Fourth would be legitimate power which would be held by someone in a position above another where they legally have the ability to enforce something. Finally, there is referent power, which is achieved through admiration or respect (Kassin, Fein, & Markus, 2011). It is easy to see how each one of these powers of authority are applicable to military leadership and could influence positive or negative actions from subordinates. A few separate accounts may help to make this more easily identified. Having so many levels of leadership within the military there are always plenty of chances that power and authority can be misused or misinterpreted, resulting in negative consequences. One such case will make this clear, United States v. Calley, also known as the “My Lai Massacre.” As a part of the declared Tet Offensive in 1968, the United States was combating the Viet Cong in Vietnam. First Lieutenant William L. Calley was in command of 1st platoon, C Company of the 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry Regiment. He was an integral part of a company mission to eliminate hostile Viet Cong in the village of My Lai. It was expected that there would be a strong amount of resistance in this village. Captain Medina had ordered Calley to kill all the Viet Cong within the village, and was somewhat vague in the orders he gave. It turned out that the village was entirely comprised of civilians, mostly elderly men, women, and children, with no sign of the Viet Cong. Lt. Calley made the decision and ordered his platoon to “waste them” and about 500 dead villagers were the result of this operation (Linder, 1999). There were several of Lt. Calley’s soldiers that did not want to kill these civilians and others that became sick from the bloodshed. Calley led by example and gave his soldiers orders to kill the civilians. Many soldiers submitted to the orders of Calley and did as they were PSYCHOLOGY OF COMBAT AND THE LAW OF WAR 17 commanded. Others postured to act like they were following orders but they really would intentionally miss their targets. There is no doubt that Lt. Calley had committed war crimes in this operation and he was accused as such. To tell the full account of these proceedings would be lengthy. In summary, Lt. Calley gave a defense that he was merely following the orders of Captain Medina to kill everyone in the village. Medina also faced charges but was never convicted as there was not enough substantial evidence that he had intended the civilians to be killed (Linder, 1999). But, Lt. Calley was eventually convicted of the atrocities that he conducted and oversaw. The court ruled that even if he was obeying the orders of his superior commander, he was obligated to disobey these as they were ‘illegal orders’ (Linder, 1999). Although there are many contributing factors to the crimes of the My Lai Massacre there is no doubt that the responsibility and influence of these crimes stem from the authority powers of the leadership. In an attempt to prevent actions such as these the United States Army has included a section in one of its field manuals about soldiers’ responsibilities: “1-121. Clear, legal, unambiguous orders are a responsibility of good leadership. Soldiers who receive illegal orders that clearly violate the Constitution, the Law of War, or the UCMJ must understand how to react to such orders. Soldiers who receive unclear or illegal orders must ask for clarification. Normally, the superior issuing the unclear or illegal order will make it clear, when queried. He should state that it was not his intent to issue an ambiguous or illegal order. If, however, the superior insists that his illegal order be obeyed, the Soldier should request the rescinding of that order. If the superior does not rescind, the Soldier has an affirmative legal obligation to disobey the order and report the incident to the next superior commander” (United States Army, 2007). PSYCHOLOGY OF COMBAT AND THE LAW OF WAR 18 During the Nuremburg Trials there were Nazi war criminals who had attempted to use the same defense of obedience. They were unsuccessful just like Lt. Calley (Crowe, 2009). The findings in Milgram’s experiments provide support that the soldiers who were following orders did so without questioning the authority of Calley. “When we look at photographs of the piles of dead women and children at My Lai it seems impossible to understand how any American could participate in such an atrocity, but it also seems impossible to believe that sixty-five percent of Milgram’s subjects would shock someone to death in a laboratory experiment, despite the screams and pleas of the “victim,” merely because an unknown obedience-demanding authority told them to” (Grossman, 2009). Looking closer to this there are several explanations to how Lt. Calley was able to have his soldiers follow these orders. Having previously seen the horrors of combat they were already desensitized to their own actions and the bloodshed which occurred. These soldiers had already had a good amount of training and had seen combat. They were prepared to encounter a large hostile force in the village. Their conditioning had already taken place and they were prepared to kill. In addition to the desensitization and conditioning, soldiers commonly diffuse the responsibility of their actions. The diffusion of responsibility in this sense goes into two separate parties: the authority figure or to the group. Calley’s platoon placed the responsibility of their actions on their leadership, whether directly above them to Lt. Calley, or all the way up to Washington. Similarly Calley diffused his own responsibility to Captain Medina. Diffusion of responsibility to a group is called “group absolution” (Grossman, 2009). There was a large amount of group absolution that took place during the My Lai Massacre. For example, if there is a group of people doing the shooting at an enemy then it is easier to participate with them and you would be more uncertain if you are the person that actually killed someone. Therefore, PSYCHOLOGY OF COMBAT AND THE LAW OF WAR 19 the guilt that you would normally feel for your own actions is diffused to the group (maybe your squad, platoon, company, or army in general) as a whole. Although the My Lai Massacre was used to illustrate the point of obedience to authority in combat, the unfortunate truth is that there are dozens of historical examples which could make the same point. Conclusion Understanding the psychology of engaging an enemy in combat, in accordance with the rules of engagement while upholding the laws and regulations of war is no easy task. Having conducted much research to complete this project it is evident that there is a large amount of information that could be tied into this topic. The information found in this paper serves as a medium to support and facilitate the learning of junior cadets in Weber State University’s Army ROTC program. Having a working knowledge of the psychology of combat, laws of war, and rules of engagement is very important for members of the military. As this paper provides a base, it would prove to be beneficial if more in-depth research and further development of this topic were to be conducted. Being able to make connections in this subject serve to produce more competent leaders of the military and members of society. PSYCHOLOGY OF COMBAT AND THE LAW OF WAR 20 Appendix A Principles of International Law Recognized in the Charter of the Nüremberg Tribunal and in the Judgment of the Tribunal, 1950. Principle I Any person who commits an act which constitutes a crime under international law is responsible therefor and liable to punishment. Principle II The fact that internal law does not impose a penalty for an act which constitutes a crime under international law does not relieve the person who committed the act from responsibility under international law. Principle III The fact that a person who committed an act which constitutes a crime under international law acted as Head of State or responsible Government official does not relieve him from responsibility under international law. Principle IV The fact that a person acted pursuant to order of his Government or of a superior does not relieve him from responsibility under international law, provided a moral choice was in fact possible to him. Principle V Any person charged with a crime under international law has the right to a fair trial on the facts and law. Principle VI The crimes hereinafter set out are punishable as crimes under international law: (a) Crimes against peace: PSYCHOLOGY OF COMBAT AND THE LAW OF WAR 21 (i) Planning, preparation, initiation or waging of a war of aggression or a war in violation of international treaties, agreements or assurances; (ii) Participation in a common plan or conspiracy for the accomplishment of any of the acts mentioned under (i). (b) War crimes: Violations of the laws or customs of war include, but are not limited to, murder, illtreatment or deportation to slave-labour or for any other purpose of civilian population of or in occupied territory, murder or ill-treatment of prisoners of war, of persons on the seas, killing of hostages, plunder of public or private property, wanton destruction of cities, towns, or villages, or devastation not justified by military necessity. (c) Crimes against humanity: Murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation and other inhuman acts done against any civilian population, or persecutions on political, racial or religious grounds, when such acts are done or such persecutions are carried on in execution of or in connexion with any crime against peace or any war crime. Principle VII Complicity in the commission of a crime against peace, a war crime, or a crime against humanity as set forth in Principle VI is a crime under international law. @ <'I <'I State Parties to the Following InternationalHumanitarian Law and Other Related Treaties as of 21-Jan-2014 ICRC "i! 1 ] .....:l Protection of Victims of Armed Confl cts GC IV Convention ()I for the Amefioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field. Geneva.12 August 1949. Convention (II) for the Amerioration of the Condition of Wounded, S ick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea.Geneva, 12 August 1949. Convention (Ill) re lative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War. Geneva.12 August 1949. Convention (IV) relative to the Protection of Civilian Personsin Time of War.Geneva,12 August 1949. AP 11977 Protocol Additionalto the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949.and re lating to the Protection of V.ctims of lntemationaJ Armed Conflicts. Geneva.8 June 19n. AP I Declaration art. 90 Dec aration provided for under article 90 AP I. Acceptance of the Competence of the InternationalFact .mding Commission according to article 90 of AP I. AP 111977 Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949.and relating to the Protection of VICtims of Non- nternational Armed Conflicts. Geneva, 8 June AP1112005 19n. Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949.and relating to the Adoption of an Additional Distinctive Emblem (Protocol Ill), 8 December CRC 1989 2005. Convention on the Rights of the ChildNew York, 20 November 1989. _ot PIQt. CRC 2000 Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Chlid on the involvement of chidrenin armed conflicN t ew York.25 May 2000. ICC Statute 1998 Rome Statute of theInternationalCrim inal Court, 17 Juty 1998. Hague Conv.1954 Convention for the Protection of CuHural Propertyin the Event of Armed Conflict. The Hague, 14 May 1954. -c.o -o .... 5 C..rn Hague Prot.1954 F rst Protocolto the Hague Convention of 1954 for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, The Hague, 14 May 1954. Hague Prot.1999 Second Protocolto the Hague Convention of 1954 for the Protection of CuHural Propertyin the Event of Armed Conflict. The Hague,26 March 1999. <r: ENMOD Conv.1976 Convention on the prohibition of military or any other hostlie use of environmental modification techniques, New Yod:, 10 December 1976. Geneva Gas Prot. 1925 Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use of Asphyxiat ng,Poisonous or Other Gases.and Warfare,Geneva.17 June 1925. BWC 1972 Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpli ng of Bacteriological (Bio ogical) and Toxin Weapons and on the r Destruction. Opened for Signature at London,Moscow and Wash ngton.10 April 1972. CCW 1980 Convention on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Certain Conventional Weapons which may be deemed to be Excessively Injurious or to have Indiscriminate Effects. Geneva. 10 October 1980. CCW Prot. I 1980 Protocol on non--detectabel fragments (J ). tij ·c .lS - International CriminalCourt Pr-otection of Cultural Property in the Event of Anned Conflc i t 3 C..rn e Environment u "0 Q) Weapons .;; c.o Q) u - CCW Prot. II 19W Protocol on prohibitions or restrictions on the use of mines.,booby-traps and other devices CCW Prot. 11119W (II). Protocol on prohibitions or restrictions on the use of incend ary weapons (Ill). r; u CCW Prot. IV 1995 Protocol on 86nd ng Laser Weapons (ProtocolIV to the 1980 Convention), 13 October 1995. CCW Prot. lla 1996 Protocol on ProhlDitions or Restrictions on the Use of Mines, Booby-Traps and Other Devices as amended on 3 May 1996 (ProtocolII to the 1980 "::l CCW Arndt 2001 Convention). Amendment to the Convention on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Certain ConventionalWeapons which may be deemed to be Excessively Injurious or to have Indiscrim inate Effects (with Protocols IIII and Ill).Geneva 21December 2001. 5 :: CCW Prot. V 2003 Protocol on Explosive Remnants of War to the Convention on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Certain ConventionalWeapons vthich may be deemed to be Excessivety Injurious or to have Indiscrim inate Effects (with Protocols IIII and Ill).Geneva, 28 November 2003. 8 ...... ewe 1993 Convention on the Prohibition of the Deve lopment,Production,Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on their Destruction.Paris 13 January 1993. AP Mine Ban Conv.1997 Convention on the Prohibition of the Use.Stockpi ing, Production and Transfer of AntiP . ersonnelMines and on the r Destruction,Os o,18 September 1997. Cluster Munitions 2008 Convention on Cluster Munitions,30 May 2008 PSYCHOLOGY OF COMBAT AND THE LAW OF WAR Appendix C Example ROE Card from Kosovo, June 1999 Peace Enforcement: KFOR Peace Enforcement: KFOR (Kosovo, June 1999) KFOR RULES OF ENGAGEMENT FOR USE IN KOSOVO SOLDIER'S CARD To be carried at all times. MISSION. Your mission is to assist in the implementation of and to help ensure compliance with a Military Technical Agreement (MTA) in Kosovo. SELF-DEFENSE. a. You have the right to use necessary and proportional force in self-defense. b. Use only the minimum force necessary to defend yourself. GENERAL RULES. a. Use the minimum force necessary to accomplish your mission. b. Hostile forces/belligerents who want to surrender will not be harmed. Disarm them and turn them over to your superiors. c. Treat everyone, including civilians and detained hostile forces/belligerents, humanely. d. Collect and care for the wounded, whether friend or foe. e. Respect private property. Do not steal. Do not take "war trophies". f. Prevent and report all suspected violations of the Law of Armed Conflict to superiors. CHALLENGING AND WARNING SHOTS. a. If the situation permits, issue a challenge: - In English: "NATO! STOP OR I WILL FIRE!" - Or in Serbo-Croat: "NATO! STANI ILI PUCAM!" - (Pronounced as: "NATO! STANI ILI PUTSAM!) - Or in Albanian: "NATO! NDAL OSE UNE DO TE QELLOJ! - (Pronounced as: "NATO! N'DAL OSE UNE DO TE CHILLOY!) b. If the person fails to halt, you may be authorized by the on-scene commander or by standing orders to fire a warning shot. FRONT SIDE 23 PSYCHOLOGY OF COMBAT AND THE LAW OF WAR Peace Enforcement: KFOR (Kosovo, June 1999) OPENING FIRE. a. You may open fire only if you, friendly forces or persons or property under your protection are threatened with deadly force. This means: (1) You may open fire against an individual who fires or aims his weapon at, or otherwise demonstrates an intent to imminently attack, you, friendly forces, or Persons with Designated Special Status (PDSS) or property with designated special status under your protection. (2) You may open fire against an individual who plants, throws, or prepares to throw, an explosive or incendiary device at, or otherwise demonstrates an intent to imminently attack you, friendly forces, PDSS or property with designated special status under your protection. (3) You may open fire against an individual deliberately driving a vehicle at you, friendly forces, or PDSS or property with designated special status. b. You may also fire against an individual who attempts to take possession of friendly force weapons, ammunition, or property with designated special status, and there is no way of avoiding this. c. You may use minimum force, including opening fire, against an individual who unlawfully commits or is about to commit an act which endangers life, in circumstances where there is no other way to prevent the act. MINIMUM FORCE. a. If you have to open fire, you must: - Fire only aimed shots; and - Fire no more rounds than necessary; and - Take all reasonable efforts not to unnecessarily destroy property; and - Stop firing as soon as the situation permits. b. You may not intentionally attack civilians, or property that is exclusively civilian or religious in character, except if the property is being used for military purposes or engagement is authorized by the commander. REVERSE SIDE 24 PSYCHOLOGY OF COMBAT AND THE LAW OF WAR 25 References Center for Army Leassons Learned (CALL). (2011, May). Rules of Engagement Handbook. Rules of Engagement Vignettes: Observations, Insights, and Lessons. Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, United States of America: Combined Arms Center (CAC). Comer, R. J. (2014). Fundmentals of Abnormal Psychology (7th ed.). New York, New York: Worth Publishers. Crowe, D. M. (2009, November). War Crimes and Genocide in History, and the Evolution of Responsive International Law. Nationalities Papers, 37(6), 757-806. doi:10.1080/00905990903230777 Emerson, W. K. (2004). Marksmanship in the U.S. Army: A Historyof Medals, Shooting Programs, and Training. Norman: Universtiy of Oklahoma Press. Geneva Concentions. (1949; 1977; 1993; 2005). 1949 Conventions and Additional Protocols, and their Commentaries. Retrieved January 2014, from Internaional Committee of the Red Cross: http://www.icrc.org/applic/ihl/ihl.nsf/vwTreaties1949.xsp Gillespie, A. (2011). A History of the Laws of War: The Customs and Laws of War with Regards to Combatants and Captives (Vol. I). Oxford, United Kingdom: Hart Publishing Ltd. Grossman, D. (2009). On Killing. New York, New York: Little, Brown and Company. International Law Commission. (1950, July 29). Prinicples of Internaional Law Recongnized in the Charter of the Nuremberg Tribunal and in the Judgment of the Tribunal, 1950. PSYCHOLOGY OF COMBAT AND THE LAW OF WAR Retrieved from International Committee of the Red Cross: http://www.icrc.org/ihl/INTRO/390 Kassin, S., Fein, S., & Markus, H. R. (2011). Social Psychology (8th ed.). (J.-D. Hague, Ed.) Belmont, California: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. King, L. A. (2013). Experience Psychology (2nd ed.). New York, New York: The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Linder, D. (1999). An Introduction to the My Lai Courts-Martial. Retrieved from University of Missouri-Kansas City Law: http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/mylai/mylai.htm Luttrell, M. R. (2007). Lone Survivor. New York, New York: Little, Brown and Company. Marshall, S. L. (1947). Men Against Fire. New York: University of Oklahoma Press. Meisels, T. (2012, December). In Defense of the Defenseless: The Morality of the Laws of War. Political Studies, 60(4), 919-935. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00945.x Olpin, M. (n.d.). Weber State University. Retrieved December 2013, from Stress Physiology Chapter: http://faculty.weber.edu/molpin/healthclasses/1110/bookchapters/stressphysiologychapter .htm Powers, R. (2013). Law of Armed Conflict (LOAC): The Rules of War. Retrieved January 2014, from About.com U.S. Military: http://usmilitary.about.com/cs/wars/a/loac.htm Scarborough, R. (2013, November 26). Rules of Engagement Limit the Actions of U.S. Troops and Drones in Afghanistan. The Washington Times. Retrieved from 26 PSYCHOLOGY OF COMBAT AND THE LAW OF WAR http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2013/nov/26/rules-of-engagement-bind-ustroops-actions-in-afgh/?page=all United States. (1976). FM 27-10 The Law of Land Warfare. Washington D. C., United States of Amercia: Department of the Army. United States. (1992). FM 34-52 Intelligence Interrogation. Washington D. C., United States of America: Department of the Army. United States Army. (2007). FM 3-21.8 The Infantry Rifle Platoon and Squad. Washington D.C., United States of America: Headquarters Department of the Army. United States Joint Chiefs of Staff. (2005). Chapter 5 Rules of Engagement. In Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Instruction 3121.01B (pp. 85-120). Washington D.C., United States of America. Williams, F. D. (1994). SLAM: The Influence of S. L. A. Marshall on the United States Army. (S. Canedy, Ed.) Washington, D. C.: United States Army Training and Doctrine Command. 27