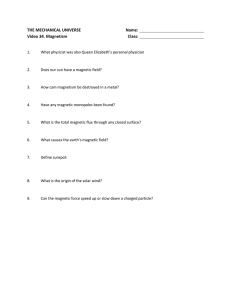

Lesson 15 - Magnetic Fields II I. Permanent Magnets

advertisement

Lesson 15 - Magnetic Fields II

I.

Permanent Magnets

A.

Over 2000 years ago in Turkey, people discovered that rocks of iron ore would

apply a force on each other. These rocks were called magnets due to their

discovery near the town of magnesia.

B.

Several interesting facts concerning these rocks were discovered:

1.

If a rod of iron touched these rocks, then it would become a magnet and

begin interacting with these rocks. The rod was said to be have been

magnetized.

2.

If the magnetized rod was placed on a leaf and floated on water, the rod

would always align itself so that it pointed approximately in the North/South

direction on the Earth.

We now know that this is because the Earth is a big magnet due to currents

inside the Earth. Thus, people were using compasses for navigation long

before we had any fundamental understanding of the cause of magnetic

fields. For instance, "Columbus sailed the ocean the ocean blue in 1492," but

the theory of magnetism dates from the 1800's.

3.

After marking the side of the rod that pointed in the northern direction as

north and the side that pointed in the southern direction as south, people

discovered that

a) the north side (pole) of the magnet repelled the north pole and attracted

the south pole of another magnet.

b) the south pole of a magnet repelled the south pole of another magnet.

S

N

N

S

N

S

N

S

N

S

S

N

Question: From the discussion above, what type of magnetic pole is near the Earth's

North Pole?

4.

Cutting a magnet in half will produce two complete magnets. This discovery

is probably far more intriguing today than it was long ago since it implies

that the cause of magnetism is not a point source (like a point charge) but an

extended source (a current loop). The search for a point source of magnetism

(magnetic monopole) is an active field of physics research. We will discuss

this further when we get to Gauss' Law for Magnets.

Summary: A considerable amount of empirical information about magnetism was

discovered using permanent magnets. This allowed for the construction of some useful

devices using permanent magnets long before any theory of magnetism existed.

However, the connection between the phenomena of electricity (discovered in Greece)

and magnetism (discovered in Turkey) prevented people from developing motors,

generators, stronger magnets (electromagnets), and electrical power. It was the

development of the battery in the late 1700's that would begin the age of electricity.

Thus, many of the conventions concerning magnets (using N/S instead of +/-) are

historical in nature.

II.

Magnetic Field and Magnetic Field Lines

A.

The concept of the magnetic field can be developed in a manner similar to the

way we developed the electric field. The magnitude of the magnetic field at a

particular point in space is found by using a moving charged particle and

determining the maximum force exerted on the particle for a given speed.

B F

qv

MAX

The magnetic field vector lies along the direction in which the moving charged

particle experiences no additional force due to its motion (no force if we remove

electric fields, gravity, etc.) with the direction of the vector given by the right

hand rule.

B.

We can build a graphical picture of the magnetic field (magnetic field lines) in a

manner similar to our work with electric fields. However, there are some

important differences due to the nature of the vector cross product that you need

to understand.

Similarities To Electric Field Diagrams:

1.

Magnetic field lines leave the north pole (like electric field lines

from a positive charge) and terminate on the south pole of a magnet (like

electric field lines on a negative charge). Thus, the direction of the magnetic

field at any point is the direction pointed to by a compass (assuming that the

Earth's magnetic field is negligible).

2.

Magnetic field lines can never cross (the magnetic field has a single value at

every point is space),

3.

The density of magnetic field lines is proportional to the strength of the

magnetic field.

The easiest way to map the magnetic field is to use iron fillings. These act like

little magnets and align with the field. A compass can then be used to determine

the direction of the arrow. Also, the strength of the magnetic field is obtained

since more iron filings will be attracted to regions of higher magnetic field.

Differences:

1.

A graph of the magnetic field lines doesn't completely specify the force on a

charged particle. This is because the force also depends on the velocity of the

particle. Stationary particles experience no magnetic force at all!

2.

A magnetic field line DOES NOT point in the direction of the force applied

on a moving charged particle. If fact, a charged particle moving the direction

of the magnetic field line experiences NO magnetic force. The non-zero

force experienced by any moving charge will always be perpindicular to the

magnetic field lines.

3.

We find that the graphs of the magnet field lines always show circulation

(rotation) and never flow! More evidence that their is no point source of

magnetism.

EXAMPLE: The following can not be a graph of the magnetic field because it has

flow and no circulation.

B

EXAMPLE: The magnetic field diagram for a magnetic dipole (the simplest magnetic

source known).

N

S

I

Current Loop

III.

Gauss' Law of Magnetism

A.

Magnetic Flux - B

Permanent Magnet

The flux of the magnetic field is defined in the same manner as the electric flux.

The units of magnetic flux are _____________________ which are defined as

B.

Experimentally, it appears that there is no point source for magnetism (ie you can

break a magnet apart and get only the north or south pole). This fact is

mathematically expressed by Gauss' Law of Magnetism:

Gauss' Law of Magnetism is one of the four fundamental equations of

electromagnetic theory known as Maxwell's Equations. These are the PHYS2424

equivalents of Newton's Laws. It says that "Magnetic Fields "Never Flow."

IV.

A.

Magnetic Force On A Current Carrying Wire

Theory

B - field

dS

I

wire

dq

The magnetic force on a differential amount of moving charge, dq, in the wire is

dF

ds

Using the definition of velocity, v , we have

dt

dF

By Calculus, we have

dq d s dq d s

dt dt

Substituting this result and using the definition of current, we have

dF I d s B

The total force on the wire is then found by summing up the force on each element of the

wire.

B

F dF

A

Since the elements of the wire are in series, they have the same current (ie I constant with

respect to integration variable dS .

B

F I d s B

A

where I is the current in the wire

B is the magnetic field vector

ds is the displacement vector point in the direction of I.

B.

Problem Solving Strategy

Step 1:

Break up the wire into segments in which the angle between ds and B and

the direction of the resulting cross product DOES NOT CHANGE.

Step 2:

You can disregard all wire segments in which I {ie. ds } is parallel to B as

Step 3:

For each remaining wire segment, find F by

d s B 0 F 0

A.

Finding d s B

B. Find the force on this wire segment using

F I d s B

segment

Step 4:

Sum segment forces using vector addition!

F

T OT AL

F

i

i

EXAMPLE: What is the force exerted by a 5.00 T magnetic field in the +y-direction

upon the 25.0 meter long wire shown below when 2.00 A of current is flowing in the

wire.

B

6m

y

6m

x

12 m

4m

2A

3m

Solution:

EXAMPLE 2: The unusual wire shape shown below is placed in a uniform magnetic

field pointing out of the page. Derive the relationship between the current, I, the wire

parameter, R, the magnetic field strength B, and the force, F , upon the wire.

B

y

R

R

x

45

R

Solution:

R

I