Sihyun Kim Dr. Jr. Elizabeth Clark English 101.2651 27 October 2005

advertisement

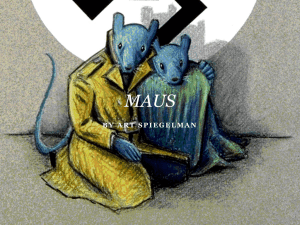

Kim 1 Sihyun Kim Dr. Jr. Elizabeth Clark English 101.2651 27 October 2005 Political Literature The graphic novel Maus by Art Spiegelman and the anthology of poems archived in the Poets Against War website serve as exemplary works of literature that shed light on the ugly aspects of war. Although these two texts do not make the effort to depict the events during war in graphic detail, the enormity of the human struggles brought about by the ordeal is nonetheless retained. By breaking down the personal lives of those affected by war, both Spiegelman and the Poets Against War convey how tragically random the violence against humanity can be. A few of the many ways that Maus and the Poets Against War website accomplish this through their depiction of: (1) the course of events as an extremely uncertain entity; (2) the unlikely heroes who are forced into combat; and (3) the indiscriminant nature of death on the battlefield. In his graphic novel Maus, Art Spiegelman depicts the Nazi persecution of the Jewish people during the Holocaust through a medium that is essentially a comic book. Although this particular method to portray the events may be deemed by some as highly inappropriate—despite their many gains in the literary world, graphic novels are still considered by many as “juvenile” —it allows Spiegelman to switch the narrative back and forth between the past and the present with ease. In doing so, he is able portray the events that occurred through the eyes of an eyewitness as well as those of himself, a person who has the benefit of knowing the eventual outcome of World War II. When Vladek, Art Spiegelman’s father, who is the focus of the main narrative in Maus, returns home from work, he tells his wife Anja that he has witnessed an outbreak of anti-Semitism downtown. When Anja suggests for the family to leave the city, Vladek responds, “If things get really bad, we’ll run back to Sosnowiec.” Immediately, Vladek Kim 2 breaks the narrative in the next panel by asking his father, “Why would Sosnowiec be any safer than Bielsko?” (37). Through the eyes of Art Spiegelman, a man who is familiar with the ultimate outcome of World War II, the answer to Vladek’s problems seems simple: leave Poland altogether. Nevertheless, the truth is that Vladek and his family had no way to know that Hitler wanted not only parts from Poland that used to belong to Germany, but also much of the entire European continent. Because the comic medium allows Spiegelman to frequently bring the readers back to the present, he is allowed to help them better understand how the uncertainty of the future brought about such tragic results to the lives of those who had failed to escape the persecution in time. In similar fashion, the poets of the Poets Against War website depict the ugly nature of war through an unconventional medium—poetry. Like graphic novels, poetry allows the writers to liberally add their own perspectives to the narration of the lives of those who are affected by war. A great example of such intermingling between the soldiers and the poets can be found in Jim Bush’s poem “How Does One Tell Them?”. Bush introduces the soldiers who are stationed in Iraq with the observation: “Laying there, so proud, with various wounds / And talking the same language as their forebears: / ‘I did it so my children won’t have to,” (2-4). The soldiers are seen as heroic figures who are willing to sacrifice their lives in order to guarantee the safety of their children back at home. However, are their sacrifices justified? “How do we tell them the other history?… / How does one tell the parents of the dead / That their son or daughter died for the free enterprise of some / Not for the free expression / Of life’s longing for happiness by the many?” (9-16). By frequently switching back and forth between the beliefs of the soldiers and those of himself, Bush is making the grim observation that the war in Iraq may not be the war as perceived by the soldiers—an operation to liberate the people of Iraq from oppression. While the Kim 3 war in Iraq can be seen as a just cause to bring democracy to the Middle East, at the same time, it can be seen as an enterprise through which big corporations of America (especially those that deal with arms) can profit. Because poetry allows Bush to handle two opposing viewpoints at the same time, he helps the reader observe that, given the uncertainty of the true reasons for America’s presence in Iraq, these soldiers may not necessarily be dying for a just cause. To add to the tragic nature of warfare, many of these soldiers who sacrifice their lives for a cause that may or may not be justified are not always “exemplary” ones. When Nazi Germany invades Poland in Maus, Vladek is sent to the frontlines after having received only a few days’ worth of army training. He has experienced only two hours of fighting when his squadron is overrun by German forces. Vladek is consequently taken as a war prisoner and is forced by the Germans to retrieve the dead soldiers who have been left on the battlefield. When Vladek recovers the body of the man he killed, he states, “His name was Jan and I knew that I killed him. And I said to myself : ‘Well, at least I did something,’” (50). The panel which depicts this moment portrays Vladek struggling to carry the corpse of the only man he has ever killed in his life. Compared to the robust German soldier, Vladek is portrayed as a delicate person who lacks the proper attires of warfare. Vladek is no superhero; he was gravely unprepared to kill another human being. Yet, the truth is that thousands of soldiers just like Vladek were thrown into combat despite their frailty as fighters. What Spiegelman ultimately accomplishes through his candid depiction of his father is his daunting portrayal of how arbitrary warfare truly is. Many who were quite adept with the rifle were brutally murdered while those who lacked even the basic accoutrements survived the war with their bodies intact. Indeed, despite the ever-changing nature of combat, the presence of unlikely heroes in the battlefields appears to be a permanent aspect of war. As illustrated by Rafe Pilgrim’s poem Kim 4 “Arms, the Boy, and Gunga Din”, the soldiers in Iraq are oftentimes young individuals who are totally unprepared to cope with the harsh realities of war. Pilgrim’s poem introduces a soldier who finally finds the time to let his thoughts wander while resting on top of a battle tank. “[T]he teenager rests his helmeted head / against the fifty caliber machine gun / and tries gingerly to ease his shoulder muscles / from the clutch of the clunky Viet Nam era / body armor,” (3-7). The poet’s decision to juxtapose a teenager with complicated weaponry seems quite bizarre. Yet, this creative discretion illustrates just how out of place these youth are on the battlefields. “Goddamitey, Goodamitey… / the boy mutters aloud, recalling / he enlisted to get a crack at college, / maybe someday counsel troubled middle-schoolers,” (58-61). According to Pilgrim, many of the youth who enlist do not fight for the grand principles that are the basis of the government’s logic behind America’s invasion of Iraq. To the contrary, most of these teenaged boys are lured by the benefits guaranteed by the U.S. government upon completion of their services in the armed forces. Ultimately, these are the heroes the United States government uses in the Second Gulf War. Like the frail Polish soldiers found in Maus, the young men who are stationed in Iraq are swiftly forced into the harsh realities of war without ever having experienced combat in their lives. However, what further adds to the dreadful nature of warfare is that war inevitably affects even those who are not directly involved in combat. When Vladek is released as a prisoner of war by the Germans, he finds himself hundreds of miles away from his home in Lublin. In order to smuggle himself from the Protectorate to the Reich, Vladek decides to find a way into a train that takes its passengers across the border. “I approached to the train man, a pole… I still had on my uniform, and I didn’t let know I was a Jew… The poles were very bitter on the Germans, so it was good to speak bad of them,” (64). The panels depicting the encounter with the conductor Kim 5 show Vladek wearing a pig mask to disguise himself as a Pole. The fact that Vladek is able to hide his identity as a Jew by covering his face with a mere pig mask reflects on Spiegelman’s ultimate message that the racial doctrine of Nazi Germany was far from being infallible. The lines separating the races were not always clearly defined, and, therefore, some Jews were able to escape persecution solely by their physical appearances. This is the indiscriminant aspect of war—even those who are not held as the target by the perpetrators of war are nonetheless affected by the atrocities of combat. Because of the indiscriminant nature of warfare, civilian are oftentimes targeted—both accidentally and intentionally—by those with arms. Ray Hewitt in his poem “The Enemy” depicts a personal experience of a soldier who has just killed another human being: There's something that I want to say, About what happened on that day. When I left you alone back there, Please don't think I did not care. It's just that I was scared of you, I wasn't sure what I should do. And if I could get back to that place, I'd close your eyes and kiss your face. Then dig your grave and say goodbye, To the boy who I saw die. The simplicity of the poem reflects on the dreadfully impersonal nature of war. The total lack of details shows how unaware the soldier is in regards to his environment and enemies. His statement: “It’s just that I was scared of you, / I wasn’t sure what I should do,” (5-6) shows how the soldier is never truly certain of who his enemies are. He is unable to identity the boy he killed as either an enemy soldier or an innocent bystander who has unfortunately become another Kim 6 casualty of war. The fact that the only physical characteristic of the boy the soldier is able to recall is his youth shows just how impersonal war can be. Because death constantly looms over the battlefield, the participants of war have virtually no time to consider who their enemies are. For this reason, countless numbers of men and women who may or may not be in uniforms are mercilessly pulled into conflict. Because works of literature like Maus and the poems from the Poets Against War website dramatically simplify the harsh realities of war, critics unsurprisingly hail them as disrespectful portrayals of the lives of men and women who have sacrificed their lives for their nation. Nevertheless, by stripping down the events that occur during wars, these writers are able illustrate the bare human emotions that are associated with the inevitable brutalities of combat. What we have to realize is that these political works of literature are not meant to be compared to those of historical documents. They are not intended to summarize the events during war in graphic detail. On the contrary, each work—whether it be a graphic novel, a poem, or a novel— serves as a unique entity that serves to illustrate just one aspect of the overall human condition during warfare.