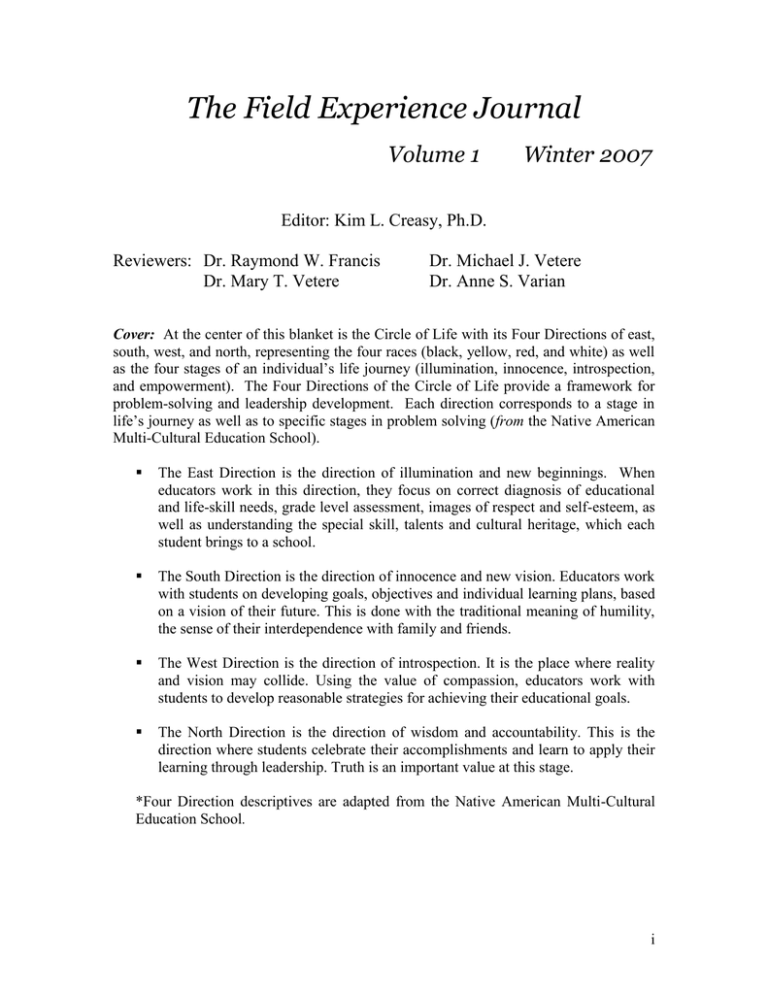

The Field Experience Journal Volume 1 Winter 2007

advertisement