The Field Experience Journal Volume 3 Spring 2009

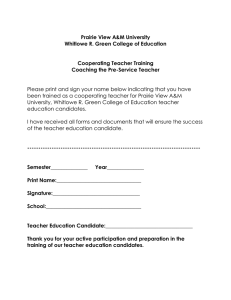

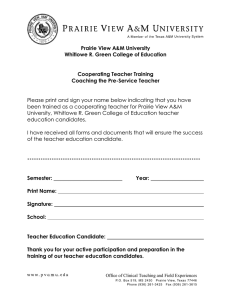

advertisement